Crime As Proxy For Disorder

...

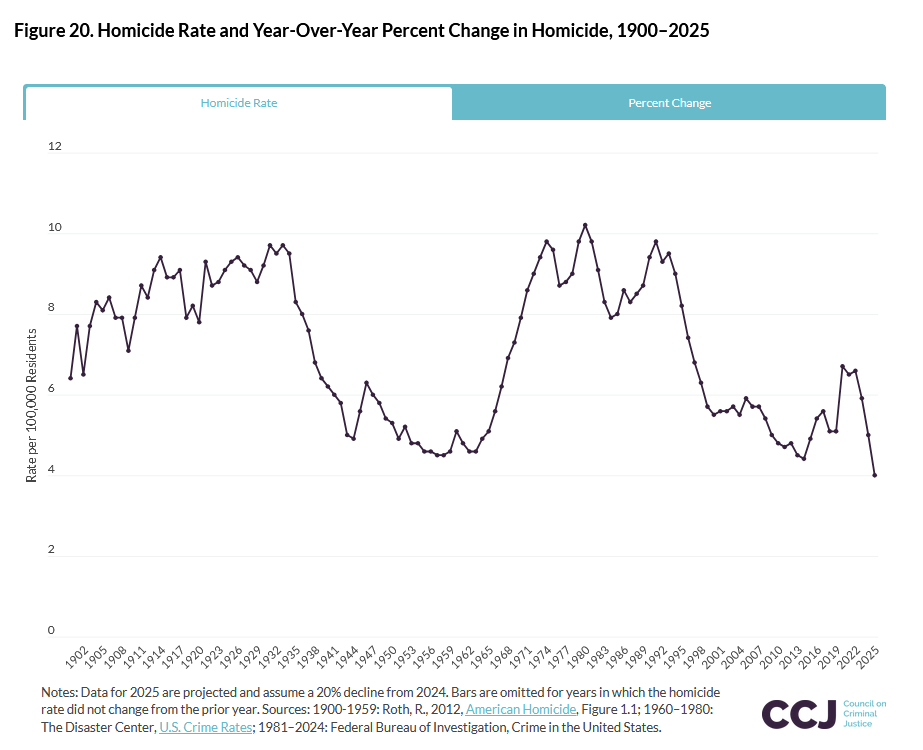

The problem: people hate crime and think it’s going up. But actually, crime barely affects most people and is historically low. So what’s going on?

In our discussion yesterday, many commenters proposed that the discussion about “crime” was really about disorder.

Disorder takes many forms, but its symptoms include litter, graffiti, shoplifting, tent cities, weird homeless people wandering about muttering to themselves, and people walking around with giant boom boxes shamelessly playing music at 200 decibels on a main street where people are trying to engage in normal activities. When people complain about these things, they risk getting called a racist or a “Karen”. But when they complain about crime, there’s still a 50-50 chance that listeners will let them finish the sentence without accusing them of racism. Might everyone be doing this? And might this explain why people act like crime is rampant and increasing, even when it’s rare and going down?

This seems plausible. But it depends on a claim that disorder is increasing, which is surprisingly hard to prove. Going through the symptoms in order:

Litter: Roadside litter (eg on highways) decreased 80% since records began in 1969 (1, 2), but it’s unclear if this extends to urban environments. New York City has a litter inspection and rating system that’s been in place since 1973, and they also report improvement - “from roughly 70 percent acceptably clean in the 1970s to over 90 percent clean now” - although citizens protest that the system doesn’t match their experience. National surveys find that the percent of people who admit to littering has gone down from 50% in 1969 to 15% today. None of these are knockdown evidence on their own, but taken together and added to the overall crime trends, the evidence for a secular trend downwards is convincing. The more recent numbers are all confounded by the pandemic, and I have no confidence in the direction of the trend since 2010.

Graffiti: There are no good data for graffiti. Most of the discussion focuses on New York, where everyone agrees the long-term trend is down since 1970. The Graffiti In New York City Wikipedia page has a “decline of New York graffiti subculture” section, which explains that in the 1980s, when “broken window” policing became popular, the police cracked down on graffiti and this worked somewhat. The only numbers are here, and they describe a decrease of 13% in calls to the graffiti hotline between 2011 and 2016. But the more recent picture, and the story in other cities, is less sanguine; in the past few years, graffiti is “a bigger problem than ever” in Los Angeles and has “gotten worse” in San Francisco. Plausibly this is the same pattern as crime, which was declining for decades until COVID and the Black Lives Matter protests caused it to rebound in 2020. A contrary data point is Britain, where graffiti reports almost doubled between 2013 - 2017; I don’t know enough about the British context to have an opinion.

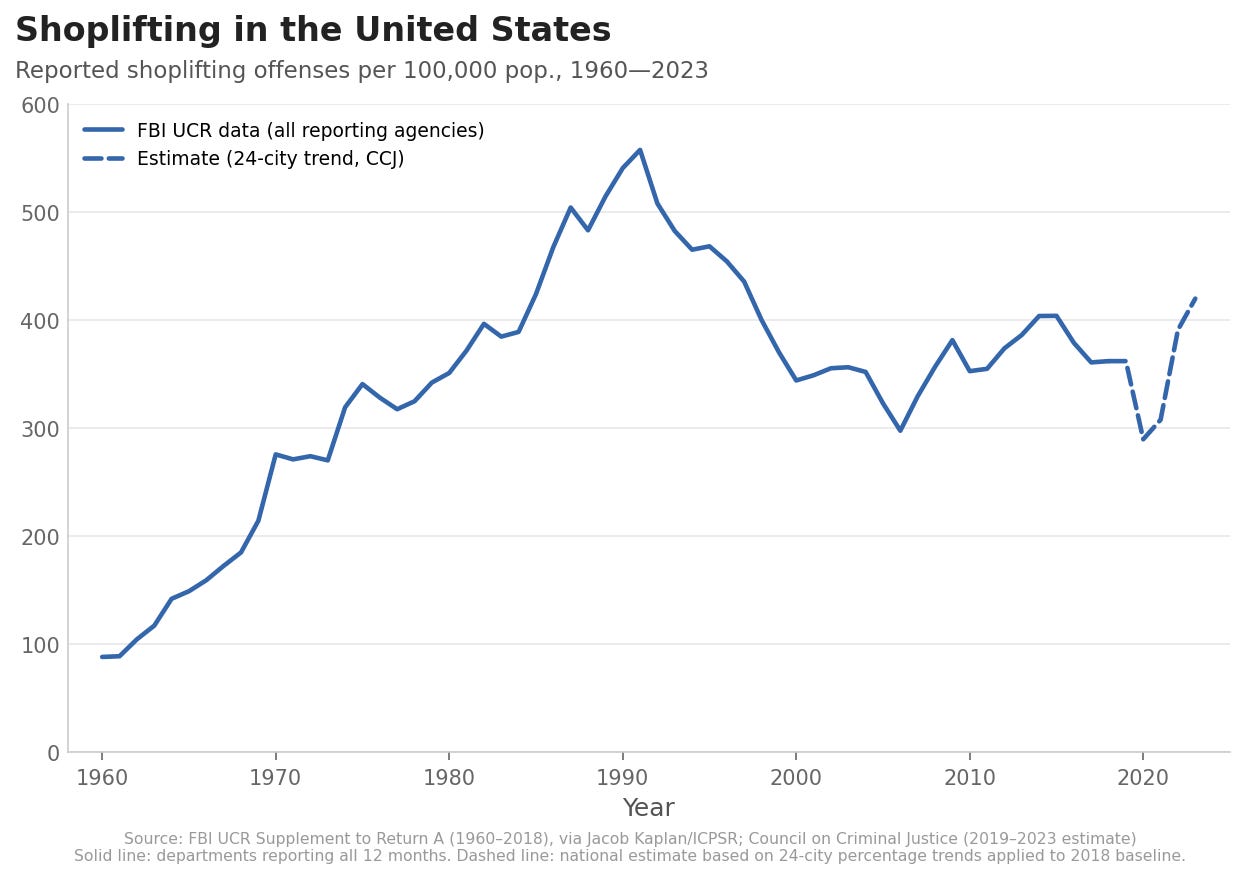

Shoplifting: According to FBI crime statistics, shoplifting remains well below historic highs, although still somewhat higher than the local minimum in 2005 (source):

Even if we worry about the increase over the 2005 low, it seems to be only about 33%, over fifteen years, which should be hard to notice. Strange!

(the FBI runs a different shoplifting reporting program, NIBRS. This does show a large increase since 2018, but is considered less reliable because new cities keep joining and so year-to-year reports aren’t comparable.)

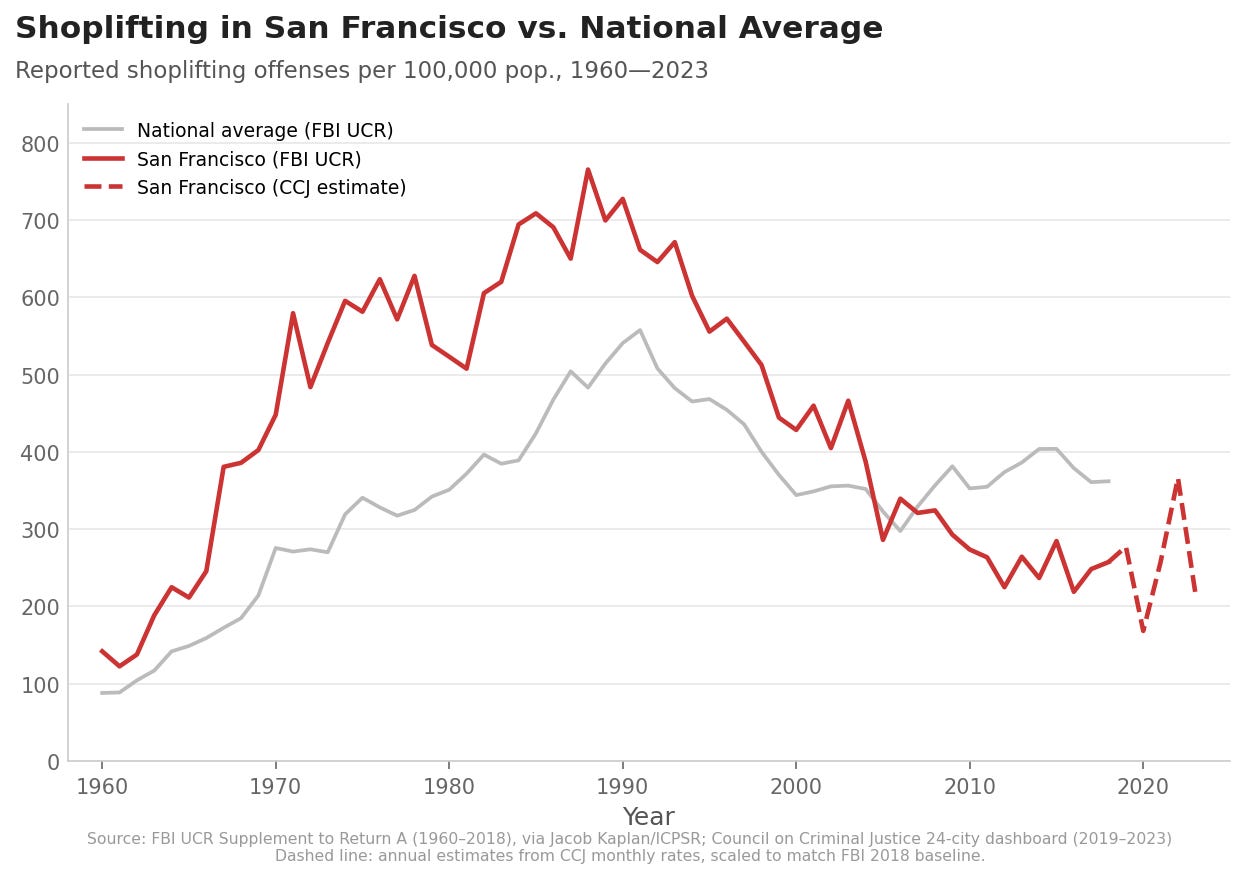

Maybe the problem is limited to a few big cities? What about San Francisco in particular?

At least in these data, it’s - if anything - less.

Okay, so could stores be failing to report to police? Some stores say they’re doing this, and there was an embarrassing incident - it might be the 2021 spike on the graph above - where two stores briefly changed their reporting policy and nearly doubled the total report number.

We need an equivalent of the NCVS - reports coming from the victims themselves. Our best bet is the National Retail Survey, from a retail organization which asks stores what percent of their inventory they believe they lose to various causes, including shoplifting.

Only about a 20% increase during the 2004 - 2022 period. The NRS is sponsored by a retail trade industry group which really wants to find shoplifting so they can lobby for better anti-shoplifting measures. In 2024 they were so embarrassed by their failure to do so that they stopped the survey entirely and sold the survey brand to an anti-shoplifting security tech company (no bias there!). The company replaced it with a survey of vibes among store owners, and dutifully reported that the vibes about shoplifting had never been worse and you needed to buy their product right away.

Now what? The survey doesn’t disaggregate by city, so maybe national shoplifting is stable, but San Francisco really is worse, and just isn’t reporting it to the police?

Might this be because there are fewer stores (everyone is buying through Amazon) and therefore even if all existing stores are crammed with shoplifters all the time, it shows up as less shoplifting? This isn’t trivially true - the number of stores has declined less than I would expect, maybe not at all - but there’s been a shift in types of stores (from big box to local). If these types have different shoplifting or reporting patterns, that might matter.

Otherwise, we’re in the awkward position where everyone (including stores) reports higher shoplifting numbers, but two datasets both disagree.

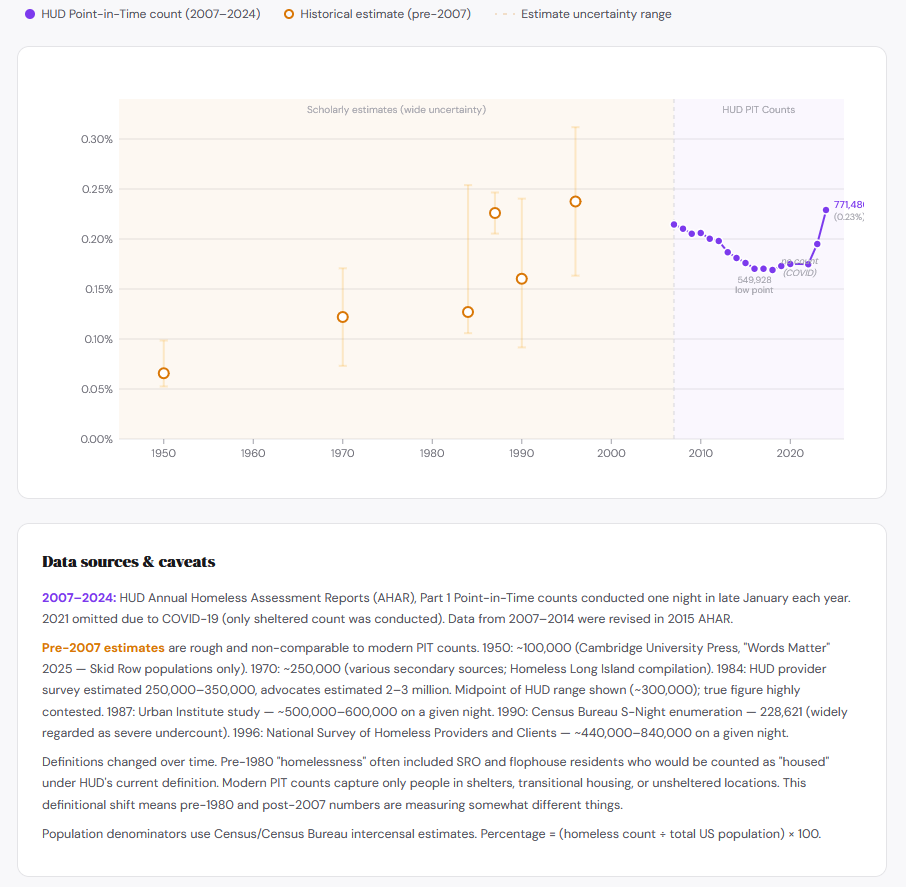

Homelessness and Tent Encampments: Here’s a graph of homelessness, courtesy of Claude:

This looks like a similar pattern to crime, although here the likely explanation for the COVID bump is the pandemic-associated rise in house prices.

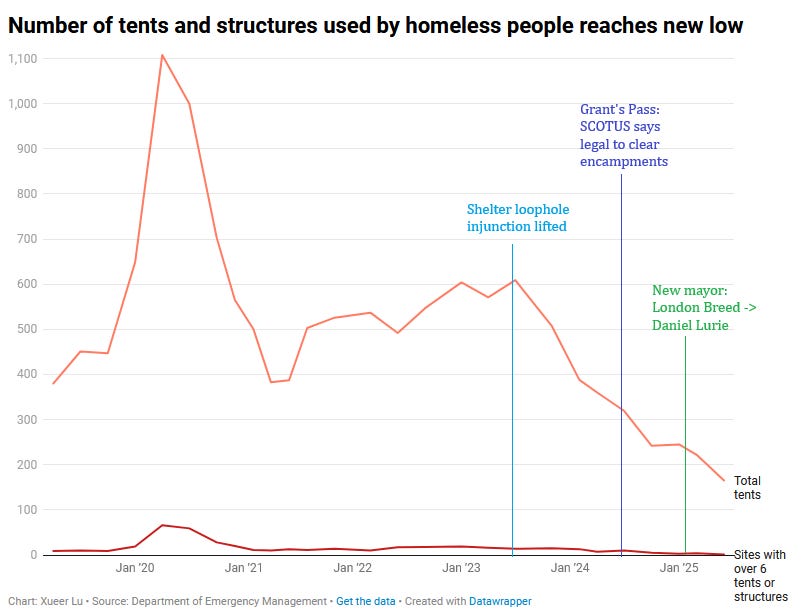

Good measures of tent encampments over long periods are hard to find. San Francisco has this one:

…but it starts in 2019, peaks during the pandemic, and then declines. This can’t really show whether 2019 was already higher than some previous year.

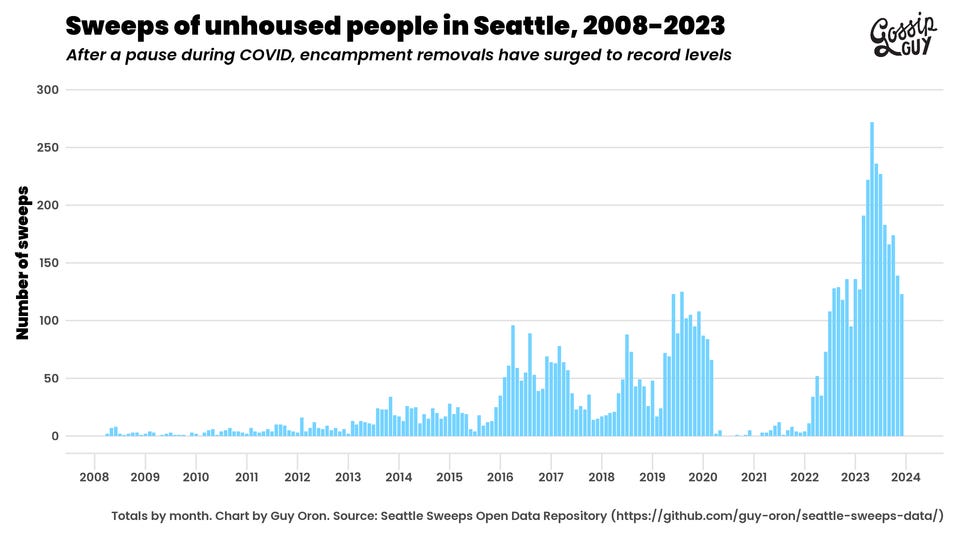

Here is an interesting graph of Seattle homeless sweeps, ie number of times the police acted against encampments:

…but it doesn’t tell us whether encampments are increasing, or the police are taking them more seriously. It does rule out a story where encampments are increasing because the police are no longer taking action - aside from the pandemic, police are taking more action than ever, at least as measured here.

People With Loud Boom Boxes In Public Places: All I have to say about this one is that it’s terrible and I hate it.

Overall, it’s surprisingly hard to find data confirming that disorder has increased:

Littering seems to be down

Graffiti is unclear, probably varies by city.

Shoplifting seems to be up 20% from generational lows, but still lower than 1990s.

Homelessness seems to be up 25% from generational lows, and equal to the 1990s.

Tent encampments are hard to measure nationally; in SF, they are below pre-pandemic levels.

All of this is compatible with a story where disorder levels mostly track crime levels: rising from 1970 - 1990, declining from 1990 - 2020, and rising a little after 2020. Crime began falling again around 2023, but the evidence on disorder, while too spotty to say for sure, doesn’t seem to include such a reversal.

So here are three theories of perceived rise in disorder:

Theory one: these concerns stem from the small (compared to secular trends) bump in these problems around 2020. Since then, crime and tent cities have declined, but people still haven’t updated because of a combination of lag time and maybe some other forms of disorder still increasing.

This feels wrong to me: people aren’t comparing the present to the golden age of 2019, they’re comparing it to the golden age of their parents and grandparents’ generation. So let’s take a longer view.

Theory two: Modern disorder was effectively impossible before 1950. There was little litter: cheap packaging and disposable bottles had not yet entered into common use. There was no graffiti: spray paint had not yet been invented. There were no boom boxes: they hadn’t been invented either. There were no cheap polyester tents. There was no pot smoke; although marijuana was known to science, it hadn’t yet entered common use.

Then there was a surge in all these bad things, starting with litter in the 1950s and continuing to cheap boom boxes around 1990. But this happened at the same time as the 1960s race riots, and white people fled to the suburbs and didn’t encounter the urban environments where these problems were worst. Around 2000, when the direction of white flight reversed and became gentrification, white people moved back to the cities, experienced the urban environment for the first time, and awareness of these problems rose.

This still doesn’t quite cash out to a secular rise in squalor and disorder. Murder rates in 1900 were still higher than today. And although there was no plastic waste, the streets of turn-of-the-20th-century cities were “literally carpeted with horse feces and dead horses”, providing “a breeding ground for billions of flies”. Let’s sharpen our focus.

Theory three: The 1930s - 1960s were a local minimum in crime and disorder of all types. The horses had been sent to pasture, but plastic litter had yet to take off. The tenements were being replaced by suburbs, but graffiti had not yet been invented. Crime rates were only half as high as the periods immediately before or after:

What caused this local minimum in crime? Claude suggests a combination of low Depression-era birth rates (small cohort of adolescents in peak crime years), the wartime economy and postwar economic boom, high psychiatric institutionalization rates, and “cultural and social cohesion” in the wake of WWII - but none of these explain why the trend should start in 1933, nor reach then-record lows by 1939.

Nor does it explain why we should update so strongly on this unique period that we still feel cheated sixty years later when things aren’t quite as good. Maybe this is just the way of things; the Romans were constantly complaining about their failure to equal golden ages centuries in the past. Still, I find it helpful to remember that although things are worse than the best they’ve ever been (except murder! murder might actually be beating 1950s record lows!), they’re not so bad by the standard of average historical periods.

Finally, theory four: the squalor and disorder of the past took different forms than the squalor and disorder of the present. Horse feces and flies instead of litter and graffiti. People crowded ten to a tenement apartment instead of sharing the subway with a boom box guy. Tobacco smoke everywhere (including restaurants and fancy hotels) instead of marijuana smoke everywhere. Crime that looked like picaresque stabbings at bordellos, or gunfights at saloons, by characters with names like Thomas Piper, the Belfry Butcher and Sarah Jane Robinson, The Poison Fiend, rather than [insert various descriptions that would get me cancelled for racism]. We look for our current problems in the past and cannot find them, then romanticize the problems the past really had.

Many people complained that by talking about crime yesterday, I was distracting from the rise in disorder. Probably people will complain today that by talking about littering and graffiti and so on, I’m distracting from some other kind of disorder which is definitely increasing - maybe open-air drug markets, or tent cities, or the boom boxes. That’s fine. But as I said when arguing with you in the comments, I think the following two statements are importantly different:

Littering, graffiti, and most violent and property crimes are down, but tent encampments and boom box playing are up. Shoplifting is stable nationally, but that could hide local variation. As some areas gentrify and others worsen, there are shifts in who experiences these problems, and the well-off highly-literate white people who set the national conversation are getting more exposed to them.

Crime and disorder are rampant, nobody feels safe anymore, cities are falling apart and the police don’t care, the West has fallen.

My goal isn’t to deny anyone’s lived experience, nor to discount the importance of solving these problems (I support the death penalty for boom box carriers). It’s to push back against a sort of Revolt Of The Public-esque sense that everything is worse than it’s ever been before and society is collapsing and maybe we should take the authoritarian bargain to stop it. On an emotional level, I feel this too - I can’t go downtown without feeling it (one of many reasons I rarely go to SF). But I don’t like feeling omnipresent despair at the impending collapse of everything. Having specific thoughts like “house prices are up since the pandemic, so it’s no surprise that there are more homeless people, and more of the usual bad things downstream of homeless people”, rather than vague ones like “R.I.P. civilization, 4000 BC - 2026 AD” isn’t just more grounded in the evidence. It’s also more compatible with living a normal life. I’m not a pragmatist who thinks you should be allowed to lie or do a biased survey of the evidence in order to live a normal life and escape despair. But I’m also not some kind of weird anti-pragmatist who makes a virtue out of ignoring evidence in order to keep despairing.

Here, as with the Vibecession, I will try to keep one foot in the statistical story, one foot in the vibes, and hold myself lightly enough not to miss whatever evidence comes next.