Record Low Crime Rates Are Real, Not Just Reporting Bias Or Improved Medical Care

...

Last year, the US may have recorded the lowest murder rate in its 250 year history. Other crimes have poorer historical data, but are at least at ~50 year lows.

This post will do two things:

Establish that our best data show crime rates are historically low

Argue that this is a real effect, not just reporting bias (people report fewer crimes to police) or an artifact of better medical care (victims are more likely to survive, so murders get downgraded to assaults)

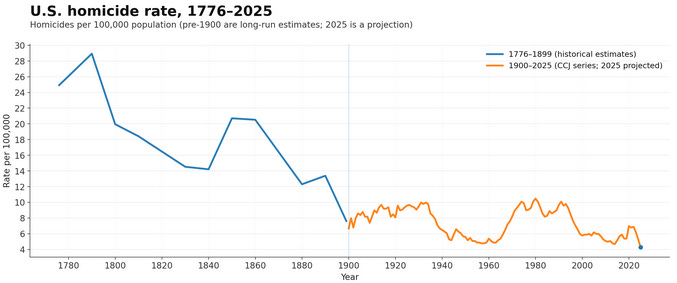

Here’s US murder rate, 1776 - present:

The pre-1900 estimates come from Tcherni-Buzzeo (2018); their ultimate source seems to be work by sociologist Claude Fisher which I can’t access. The 1900 - present data come from historian Randolph Roth’s American Homicide and the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting, both by way of the Council on Criminal Justice.

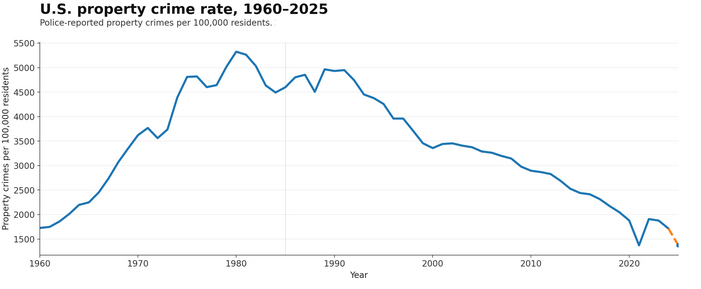

There’s less historical data for property crimes, and the nature of property has changed throughout history in ways that make numbers incommensurable (is it bad if we have a higher grand theft auto rate today than in 1840?) I was only able to get good data since 1960, but here it is:

The 1960-2023 data come from FBI Data Explorer via Vital City; the 2024 and 2025 data come directly from the FBI website, with 2025 annualized via incomplete Jan - Oct data. This one may or may not be an all-time low, but it’s pretty good.

These data are counterintuitive. Are they wrong?

Could This Be An Artifact Of Reporting Bias?

People could be so inured to crime that they stop reporting it to the police. Or the police could be so overwhelmed that they stop accepting the reports. Since most crime statistics are based on police reports, this would look like crime going down. There’s some evidence of this happening in specific situations, like shoplifting in San Francisco. Could it be the whole effect?

No, for three reasons.

The National Crime Victimization Survey is a government-run survey of a 240,000 person nationally representative sample. They find random people and ask whether they were the victims of crimes in the past year. This obviously doesn’t work for murder, but they keep statistics on rape, assault, larceny, and burglary. Their numbers mostly mirror those reported by police and used in the usual statistics about crime rates. But here there’s no extra step of needing to trust the police enough to make a report: the surveyors ask the victims directly. Although there could be biases in this methodology too, it would be an extraordinary coincidence if they exactly matched the proposed reporting bias to police.

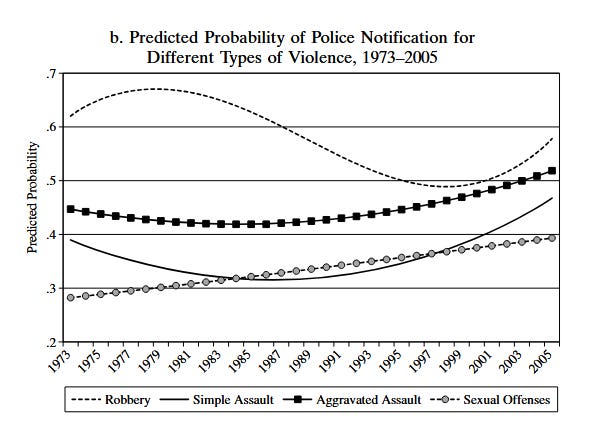

Also, you can use NCVS and police reports to calculate reporting rates directly. Overall, they seem to have increased over time - did you know that the 9-1-1 emergency hotline wasn’t available in most areas until the 1970s? This is especially true for aggravated assault (which will become important later).

There’s one caveat - FBI statistics show that crime had a small local peak in 2020/2021, then fell in 2023 - 2025. The most recent NCVS survey, in 2024, shows a smaller fall, leaving us still above 2019 lows. There’s some debate over whether the FBI vs. NCVS numbers are better for the 2022 - 2025 period, but they don’t change the overall trajectory or the fact that we’re at least close to record lows.

Murder is almost always reported to and investigated by police; there’s a person who should be alive but isn’t, and people inevitably notice and care about this. Therefore, reported murder rates should be accurate. But murder has decreased at about the same rate as every other crime. Therefore, we should believe that other crimes have gone down too (for the objection that murder statistics are unusually untrustworthy because of improving medical care, see below).

And car theft is consistently reported to the police, because insurances require a police report before they will compensate the lost car. So even if the victim doesn’t trust the police to do a good job investigating, they report it anyway. But car theft rates have declined at similar rates to other crimes. This is further evidence that the decline can’t be explained by poor reporting.

Could This Be An Artifact Of Improving Medical Care?

Good medical care can help victims survive, transforming murders into attempted murders or aggravated assaults (after this: “AM/AA”). If the same gunshot is only half as likely to kill someone today as it would have been in 1960, then a seemingly-equivalent murder rate would correspond to twice as many people getting shot. Could this explain the apparent decline in murders?

The argument would go something like: murder is the only crime that we’re completely sure gets reported consistently. But the murder rate is artificially depressed by improving medical care. Therefore, maybe the seemingly-low murder rate is because of the medical care, the seemingly-low rates of other crimes are because of reporting bias, and actually crime is up.

We’ve already seen that several parts of this can’t be true: other crimes like car theft are reported consistently, and among the inconsistently reported ones, reports are more often increasing than decreasing. But the part about murder also fails on its own terms.

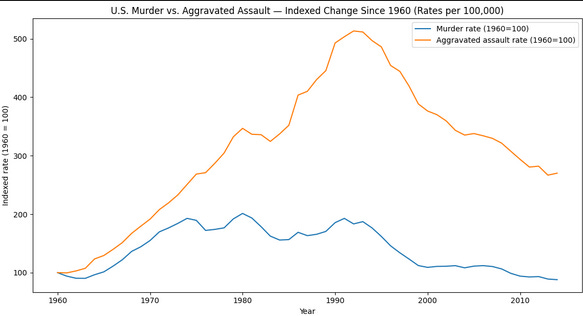

The source for the claim that improving medical care lowers murder rates is Harris et al, which analyzed crime from 1960 - 1999 and concluded that “the principal explanation of the downward trend in lethality involves parallel developments in medical technology”.

They found that aggravated assaults rose faster than murders during this time; AAs increased by 5x, while murders “merely” doubled. Under the reasonable assumption that these crimes have similar generators, they suggested that the cause was improved medical care saving the lives of those who would have otherwise died, converting potential murders into AAs. If murders rose at the same rate as AAs, then the true murder rate could be up to 3x higher than reported.

But more recent research, especially Eckberg (2014), challenges this story. Eckberg argued the AA vs. murder divergence was caused by two things: first, better reporting of aggravated assault (as discussed above), and second, police being more likely to classify borderline causes as aggravated assault rather than regular assault.

He turned to the National Crime Victimization Survey, which escapes reporting bias and police classification flexibility. In these data, AAs and murder rose at about the same rate. He concluded that (my emphasis):

Their lethality trend is not compatible with the previous finding [of declining lethality] across 1973 through 1999, remaining stable rather than falling. After 1999, both Uniform Crime Reports (UCR)-and NCVS-based measures indicate increases in lethality.

How is this possible, since medical technology has certainly improved?

It seems that gun injuries are getting worse over time. Livingstone et al studied changing characteristics of gunshot victims between 2000 and 2011. They found that the proportion of patients with 3+ wounds almost doubled (13% → 22%) during that period (p < 0.0001). Manley et al did a similar study looking at 1996 - 2016 and found a similar result, saying that “wounding in multiple body regions suggests more effective weaponry, including increased magazine size”. A letter by top trauma doctors to the American Journal of Public Health describes:

…increases in gunshot injuries per patient, gunshot injuries to critical regions (head, spine, chest), and gunshot injuries to multiple regions. Injury Severity Scores were also higher over similar intervals correlating with lower probability of survival.

Despite which

…patients surviving evaluation in the emergency department had no significant increase in mortality. Major strides in trauma care have occurred over the last two decades, and nationwide organizational changes have expanded the delivery of these improvements.

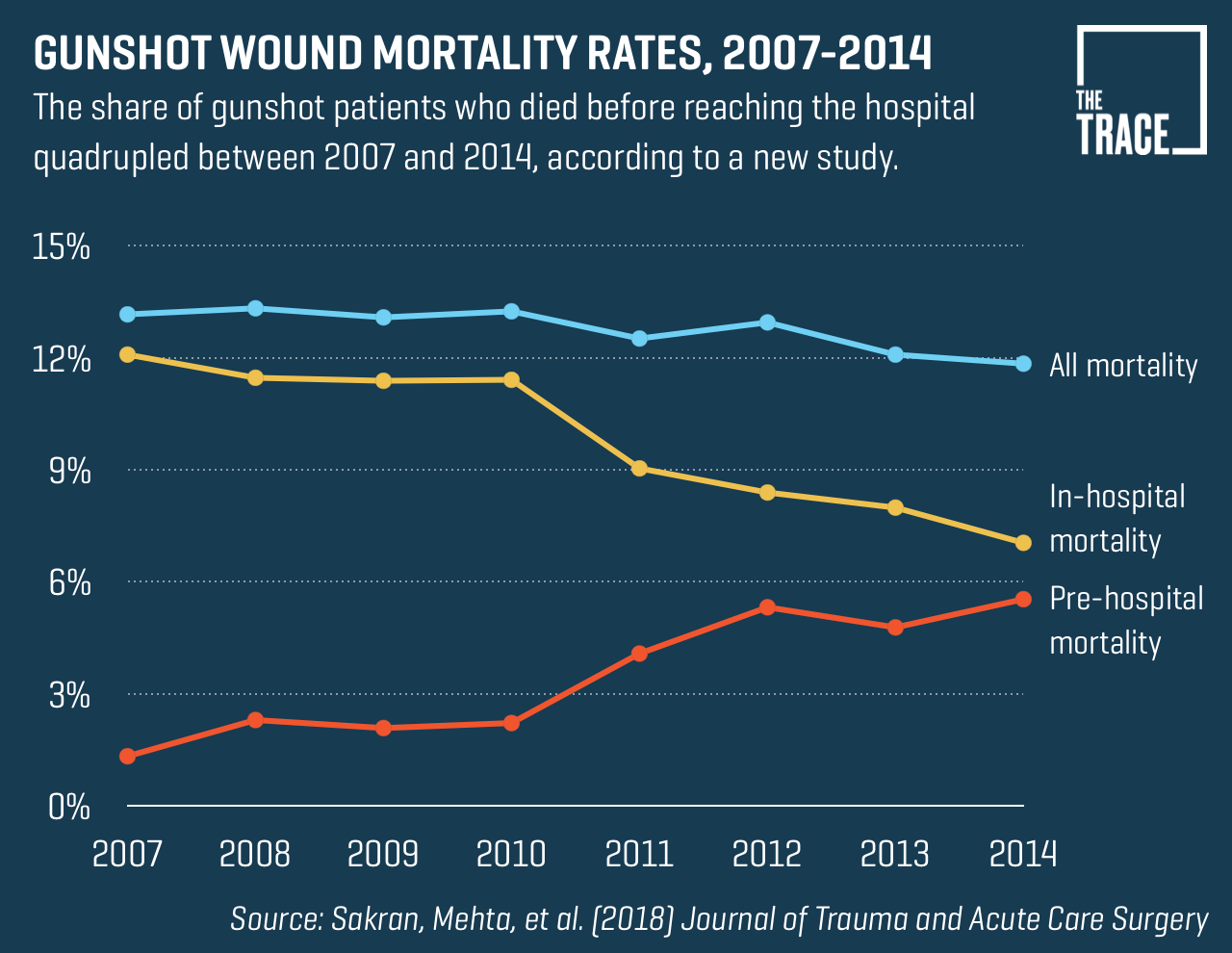

Sakran et al, studying the 2007 - 2014 period, have an especially vivid portrayal of this pattern:

Likelihood of dying before hospitalization - primarily dependent on injury severity - went up. Likelihood of dying in the hospital went down, probably because trauma care improved (although this could also be because more of the sickest patients died before entering the hospital). Cook et al studied gunshot lethality during a slightly different period - 2003 - 2012 - and also found that it stayed the same overall.

There are three plausible explanations for gun injuries getting worse over time:

Improved weapons technology (e.g. switch to semi-automatics)

Shooters have been in criminal communities a long time and have a good intuitive sense of the likelihood that victims survive. As medical care improves, shooters invest more effort into harming their victims in order to maintain the same likelihood of lethality. For example, it might have been 1970s conventional wisdom in criminal communities that you only had to get one shot in, but it might be 2020s conventional wisdom that you have to get at least three shots to be sure.

Changing nature of violence. Many late-20th-century shootings were robberies gone wrong. But armed robberies have decreased even more dramatically than other crimes, because of store security cameras and lower reliance on cash. In an armed robbery gone wrong, the shooter probably just shoots the clerk once and gets out. Now that there are fewer armed robberies, a higher percent of shootings involve shooters who really want to kill the victim and are working hard to make it happen. That means more gunshots to more critical areas.

I conclude that the 1960 - 2000 data are weak, but the best research (Eckberg’s) suggests stable lethality per act of violence during this time. The 2000 - 2020 data are stronger, and also suggest at-least-stable lethality per act of violence, and can even tell us why: severity of injuries is increasing at a rate comparable to the improvement in medical care.

Is it suspicious that two very different things are changing at exactly the right rate to cancel one another out, let us ignore the whole problem, take crime statistics at face value? I think so! It would be less suspicious if most of the explanation was (2) - the shooters specifically compensating for increased victim survival rates - but I can’t tell if this is true or not. But keep in mind that the alternate explanation - that apparent crime rates are around the same as in 1960 because a true increase in crime rates has been masked by improved medical care and reporting bias - also requires two things changing at exactly the same rate in a suspicious way. If we’re going to do this, we ought to at least take the suspicious cancellation that’s supported by the data.

Why are so many forms of crime (murder, violent crime, and property crime) at or near historic lows? This is an unsolved question among criminologists, but proposed answers include:

High crime in the 1970s was caused by lead poisoning, but lead levels have declined precipitously (plausible but controversial)

Mass incarceration worked (very plausible for 1990s, but hard to explain why crime continues to decline even as incarceration rates decrease)

Increased abortion rates among the underclass prevented the birth of future criminals (very strongly challenged, but proponents still stand by it)

High crime in the 1970s was caused by the drug trade. The rise of cell phones has replaced street-corner drug dealers with “a guy I know from college”, which necessitates fewer street-corner turf wars.

Security cameras and DNA testing have increased clearance rates. The smart criminals know they’ll be caught and don’t commit crimes; the dumb criminals commit one crime, get caught, go to prison, and are out of commission for a while.

Increased psychiatric care: all of the would-be criminals are on SSRIs, antipsychotics, and Adderall.

Welfare programs, community policing, Hugs Not Crime After School Activity Circles, and/or whatever Palantir is doing actually work.

The anti-police backlash after Black Lives Matter increased crime so much that it caused a backlash-to-the-backlash that gave police even more community support and resources than they had before (this is my explanation for why crime dropped so profoundly in 2023, 2024, and 2025 in particular)

All the criminals are too addicted to video games and Instagram to commit any crimes.

Zooming out a level, why shouldn’t crime be at historic lows? We’re a safetyist culture. Car accident fatalities are near historic lows after we mandated airbags and other safety features. Childhood injuries and deaths are near historic lows after we mandated that all playgrounds be made of Styrofoam. Various forms of hospital error are near historic lows after we let lawyers sue hospitals for zillions of dollars if they weren’t. Why should crime be the exception?

The next question is: why do people’s intuitions clash so violently with the statistics? More on that soon.