Prison And Crime: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

...

Do longer prison sentences reduce crime?

It seems obvious that they should. Even if they don’t deter anyone, they at least keep criminals locked up where they can’t hurt law-abiding citizens. If, as the studies suggest, 1% of people commit 63% of the crime, locking up that 1% should dramatically decrease crime rates regardless of whether it scares anyone else. And blue state soft-on-crime policies have been followed by increasing theft and disorder.

On the other hand, people in the field keep saying there’s no relationship. For example, criminal justice nonprofit Vera Institute says that Research Shows That Long Prison Sentences Don’t Actually Improve Safety. And this seems to be a common position; William Chambliss, one of the nation’s top criminologists, said in 1999 that “virtually everyone who studies or works in the criminal justice system agrees that putting people in prison is costly and ineffective.”

This essay is an attempt to figure out what’s going on, who’s right, whether prison works, and whether other things work better/worse than prison1.

Everyone’s Favorite Part: The Definitional And Methodological Issues

I was able to find three really high-quality review articles on this topic:

Nagin et al, 2009. Written by a team of criminology and statistics professors. None of them appear to have any glaring biases or conflicts of interest.

Berger et al, 2021. Written by a team from the pro-tough-on-crime nonprofit Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. This was well written and tried hard to stay neutral, but I still interpret it as the pro-incarceration faction presenting their side of the case.

Roodman 2017. Written by a researcher at the effective altruist nonprofit Open Philanthropy Project, which was trying to determine whether to continue to advocate decarceration. They (Roodman’s bosses) had already started some advocacy, so Roodman admits he is at risk of a soft-on crime bias. This was extraordinarily well-written, and is one of the most careful meta-analyses I have seen on any topic - Roodman tried to get data from every study and replicate it himself and test all of the assumptions - but I am still interpreting it as the anti-incarceration faction presenting their side of the case.

Each of these reviews gets deep into the statistical weeds to bolster or discredit their favorite/least favorite studies, and in most cases I wasn’t able to have a strong opinion on who was right. My strategy was to use the pro-incarceration and anti-incarceration reviews to determine a sort of “Overton window” of what smart people thought they could get away with claiming. Then, if the window was very wide and I couldn’t figure out where I landed, I used the apparently-unbiased Nagin as a tiebreaker.

All three reviews separate the possible effects of long prison sentences into three bins:

Deterrence. Would-be-criminals can consider the severity of punishment before committing their crimes, and, if the punishment is too high, decide it’s not worth it.

Incapacitation: While criminals are in prison, they can’t commit more crimes (except within the prison walls; we ignore these for sake of simplicity). Longer sentences mean that non-prisoners get a longer time free from prisoners’ criminal activities.

Aftereffects2: Once a criminal is released from prison, they either reoffend or don’t. Perhaps long prison sentences reduce reoffending, because the prisoners have had more time to be “scared straight” or “find God” or get connected to good social services. Or perhaps long prison sentences increase reoffending, because the prisoners have lost their outside social connections, formed new criminal social connections in prison (eg joined gangs), or just forgotten how to survive on the outside.

The earliest studies investigated these three effects through correlational studies: do states with longer sentences have less crime / less recidivism / etc ? These reviews all express skepticism about this method: it’s the old “correlation vs. causation” problem again. What if the causation is backwards, and more crime causes longer sentences (because high-crime states want to get tough and fight back)? Or what if they’re only linked through some third concept? For example, suppose all states are either generically tough-on-crime (with long sentences, more police, more social sanctions on criminals) or generically soft-on crime (short sentences, less police, etc). Then any part of the tough-on-crime package would confound all the others (eg if more police decreased crime, it would falsely look like longer sentences did).

In order to avoid these problems, all three reviews recommend experimental and quasi-experimental studies. We’ll look into the exact methodologies later, but typical papers would look at crime rates just before or after new sentencing laws were passed, or at very similar crimes which quirks of the sentencing regime punish very differently. Roodman and Nagin look only at experimental or quasi-experimental studies, whereas Berger sometimes carefully examines some of the better and more-carefully-controlled correlational evidence.

Let’s see how each one treats these three bins.

Deterrence

Rational actors consider the costs and benefits of a strategy before acting; this model has been successfully applied to the decision to commit crime. Studying deterrence is complicated, and usually tries to tease out effects from the certainty, swiftness, and severity of punishment; here we’ll focus on severity.

A typical study here is Helland and Tabarrok 2007 (you may know Alex Tabarrok from Marginal Revolution). They looked at California’s famous Three Strikes law, which says that a criminal who has already committed two major crimes will automatically get a sentence of twenty years to life on their third.

This is potentially a good way to study deterrence, because one group of criminals (those with no strikes) will get a normal sentence for their next crime, but another (those with 2 strikes) will get a long sentence. So if long sentences have a strong deterrent effect, we expect the second group to commit far fewer minor crimes than the first.

It would be naive to jump straight to doing this study in the whole population, because people with multiple past “strikes” are more likely to be hardened criminals, and should be expected to offend more in the future. So H&T did something more complicated. They looked at criminals with one strike, plus a second crime that was on the border of being “major” enough to earn a second strike. Some had good luck at their trial, got their offense downgraded to a “minor” crime, and continued to only have one strike; others had bad luck, got their offense upgraded to a “major” crime, and earned a second strike. Now we have two groups with exactly equal criminal histories but different number of strikes! That means one group will be punished more severely for their next crime than the other. How much deterrent effect does this have?

They found that 48% of the one-strike group and 40% of the two-strikes group got arrested per year, a difference of 17%.

They re-ran their analysis with data from other states, and found the same pattern in Texas (the only other state with a three-strikes law) but not elsewhere. This reassured them that it’s a real effect of deterrence and not just an artifact.

Still, Helland and Tabarrok are not impressed by this result. Yes, we decreased crime by 17%. But it took an extraordinarily severe threat. The Three Strikes Law raised the expected sentence for a third crime from ~5 years to ~20 years, so each extra year in the threatened sentence decreased crime about 1%. If you think about this economically, it’s a bad deal; it takes $150,000 worth of incarceration costs to deter one crime, but the social cost per crime is (they say, citing another economics paper) about $34,000.

And most deterrence isn’t this strong. Only 4% of California crime is committed by offenders with two previous strikes, and there’s no political will to impose these kind of 20+ year sentences on first-time criminals. So most deterrence will look more like the Proposition 36 proposal we discussed last month, which increases shoplifting sentences from six months to three years. If we use H&T’s numbers (probably inappropriate since there may be nonlinear effects), we would expect that section of Prop 36 to deter crime by 2%.

There are two other considerations that might increase or decrease our estimate of deterrence.

First, how sure are we that the police caught all the crimes here? In general, only about 50% of violent crimes and 10% of property crimes are caught. Should we multiply these numbers by somewhere between 2-10x?

I think in this case the multiplier should be somewhat less. The subjects in this study were on parole or probation from their previous strike, so they were more likely to be monitored by police. And they’d already gotten caught twice, which suggests they’re either worse at crime than average, or operating in areas with better-than-average police coverage. Still, maybe we should multiply by, idk, 2-5x?

This won’t affect our percentages: we expect that arrests are some fixed proportion of offenses, so if a criminal gets caught 17% more often, they’re probably committing 17% more crimes (however many that is). But it might affect our estimate of the social costs of crime. Instead of saying that $150,000 worth of incarceration costs prevents $34,000 worth of crime, maybe we should say that it prevents $68,000 - $170,000 - which, at the higher end of the range, would be economically break-even.

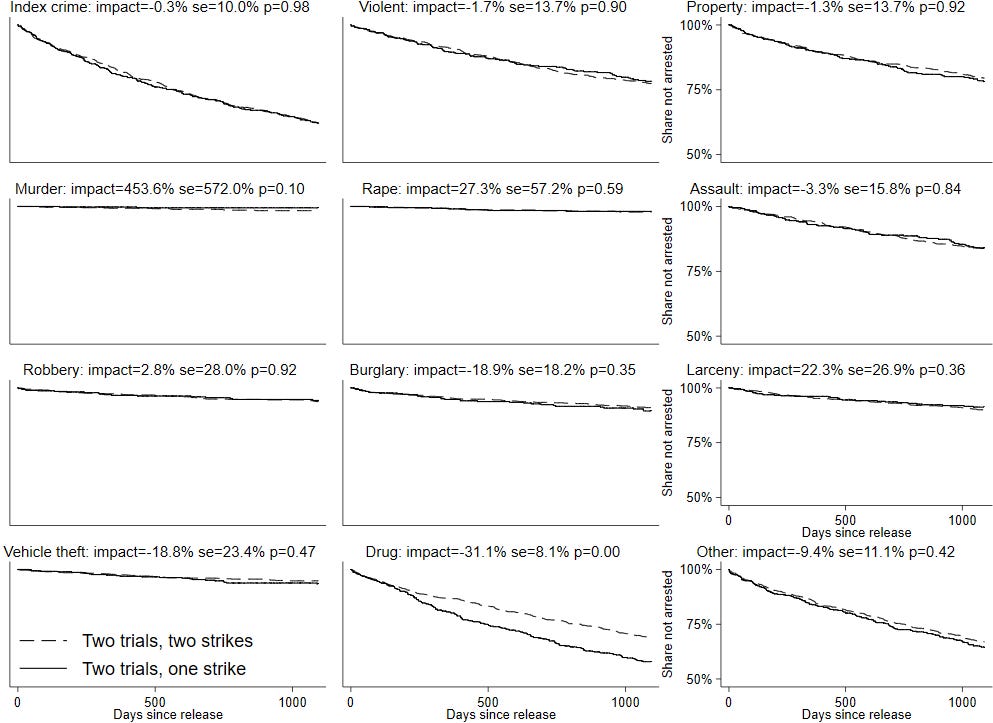

Second, what kind of crimes are we deterring? Here Roodman, the anti-incarceration review, analyzes H&T’s data more thoroughly and finds that their effect is concentrated in the least severe crimes:

That is, overall crime decreased 17%. But violent crime decreased only 1.7% (not significant). The only crime where the decrease reached statistical significance was drug crime (31%).

Should we take this completely seriously and say that the Three Strikes Law only deterred drug crime? I’m not sure. The argument against is that drug crime was the most common category of crime in this sample, so it’s possible that the study was powered to detect decreases in drug crime but not in other categories. In favor of this interpretation, vehicle theft (a category sometimes found to be especially deterrable in other studies) went down 19%, similar to the overall headline number - it just didn’t reach statistical significance. But against this interpretation, larceny (minor robberies like shoplifting) went up 22%. This is obviously random noise, and it would be unfair to ignore the larceny result but count the (equally weak) vehicle theft result just because it agrees with our priors. I think when you average everything together, it really does look like the effect on everything except drugs is small.

Maybe it’s hard to deter violent crimes (because these are executed in a fit of passion), it’s hard to deter property crimes (because criminals need the money), but it’s easier to deter drug crimes (because people make more rational decisions about whether or not to use drugs)?

(How much do we care about drug crime? Tabarrok says somewhat, because drugs can be a “gateway crime” that gets people into the criminal lifestyle. Roodman says not much. It’s either personal use, which is mostly victimless, at least compared to other crimes. Or it’s dealing, which is demand-driven and almost impossible to stop through incarceration - if you lock up every member of Cartel A, that just creates a lucrative niche for Cartel B to step in and fill.)

So a pessimistic interpretation (which I find hard to avoid) is that an extra year added on to a prison sentence decreases drug crimes by 2%, and other crimes some unmeasurably-small amount that may or may not be literally zero.

I went into this one study in depth so you have an idea where these numbers are coming from, but here’s a broader survey of deterrence research:

Ross 1982 investigated the effects of some widely publicized laws that increased penalties for drunk driving. They found that it decreased drunk driving 66% (!) in the year the law came out, but this effect gradually faded to zero over the next three years. The most likely explanation is that the publicity around the new law got people excited, but nobody really knows the laws around drunk driving anyway (do you know what the range of sentences for DUI in your jurisdiction is?) and so once the excitement of “law is stricter now!” faded from memory, the law had no effect.

Drago et al 2009 investigated an Italian mass release of prisoners, where they were released with the caveat that if they were rearrested, they would have to serve not only the new sentence for the new crime, but the remainder of their original sentence too. This created a regime of very different punishments for the same crime; someone who was originally arrested for murder but released would have to serve a sentence for murder if (for example) they got caught shoplifting. They found that each extra month of a potential sentence decreased reoffending rates by 0.16 pp (1%) per month. This is on the high side of estimates, but in general we’ll find European studies find stronger effects from imprisonment than American studies; this is probably because Europe has lower incarceration rates in general and has yet to “pick the low hanging fruit”.

Abrams 2012 examined jurisdictions that passed laws that added “sentence enhancements” for gun crimes, under the theory that if gun crimes (but not non-gun crimes) decreased after the enhancements, that was probably a true deterrence effect. They found no impact from mandatory minimums, but “add-on” enhancements decreased gun robberies by 5-15% and gun assaults by 0-1%. These were heterogeneous laws, but it looks like typical gun add-ons are about ten years, so this once again looks like a 1% decrease per extra year of prison sentence, concentrated on the least severe crimes (ie robberies are less severe than assaults). Roodman reanalyzes this, finds some flaws in the data, and comes up with a lower estimate, but I’m going to nervously ignore this for now.

I think all four of these studies are consistent with an extra year tacked on to a prison sentence deterring crime by about 1%. All studies start with significant prison sentences, and don’t let us conclude that the same would be true with eg increasing a one day sentence to a year-and-a-day.

Helland and Drago et al both suggest that deterrence effects are concentrated upon the least severe crimes. I think this makes sense, since more severe crimes tend to be more driven by emotion or necessity.

Of our three reviews, Berger (pro-longer-sentences) concludes:

There is considerable room for disagreement about deterrence, but the legitimate disagreement is about the magnitude and conditioning of the effect, not the existence. Arguments that punishments always deter and never deter are equally and oppositely wrong. Given that sanctions do have some deterrent effects, eliminating them altogether would produce some increase in crime. A policy argument for eliminating them would require justification that the elimination would produce benefits sufficient to offset the additional crimes.

Roodman (pro-shorter-sentences) concludes:

We are left with little convincing evidence that at today’s margins in the US, increasing the frequency or length of sentences deters aggregate crime.

Nagin (neutral tiebreaker) says that he will not discuss it in his review since he wants to put it in a different paper, but having found the different paper, he concludes:

My main conclusions are as follows: First, there is little evidence that increases in the length of already long prison sentences yield general deterrent effects that are sufficiently large to justify their social and economic costs. Such severity-based deterrence measures include “three strikes, you’re out,” life without the possibility of parole, and other laws that mandate lengthy prison sentences. I conclude, as have many prior reviews of deterrence research, that evidence in support of the deterrent effect of various measures of the certainty of punishment is far more convincing and consistent than for the severity of punishment.

My own conclusion after reading all three agrees with Nagin: deterrence effects exist but are quite small, probably too small to justify longer sentences on their own.

As we’re about to find out, incapacitation effects so dwarf deterrence effects that it’s not really worth debating the exact magnitude of the latter.

Prelude To Incapacitation: Superoffenders

In a moment, we’ll look at studies addressing the effects of incapacitation. These studies will be hard to interpret. But before we get there, there’s an argument that this shouldn’t be hard at all. It should be very easy.

Crime follows a power law: just as a tiny number of billionaires hold much more wealth than thousands of ordinary people, so a tiny number of “superoffender” criminals commit more crime than thousands of ordinary people. A genre of article presents evidence for this, then implicitly asks: why can’t we just lock up the tiny number of superoffenders, greatly decreasing crime with only a small change in the incarceration rate?

So for example:

Cremieux discusses a Swedish study showing that 1% of Swedes commit 63% of the violent crime.

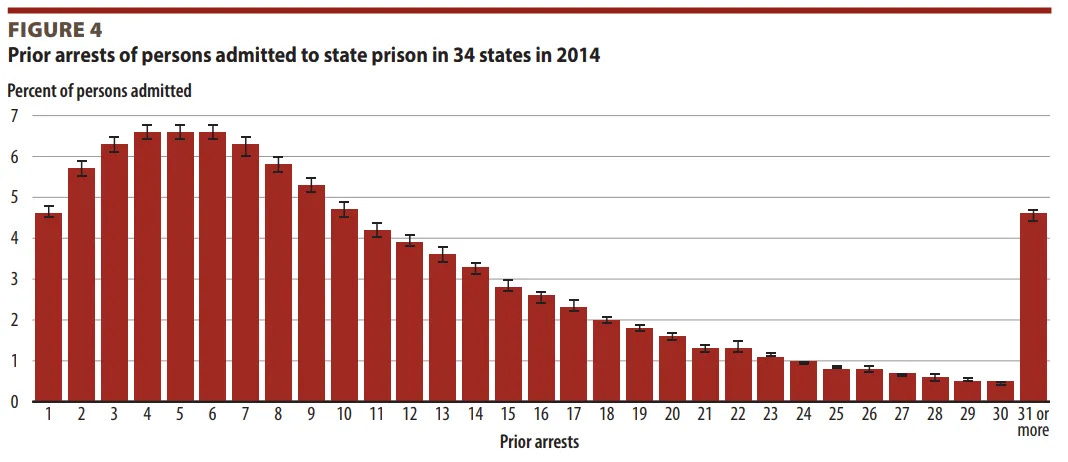

Inquisitive Bird presents data from Durose and Antenangeli showing that the median US prisoner already had ten previous arrests.

The New York Times discusses how 327 individual shoplifters with 20+ arrests each are responsible for a third of the shoplifting in New York City!

Vollaard et al in the Netherlands find that a ten-strikes law decreased crime 25%; the average person affected had 31 past convictions and plausibly committed >250 crimes per year.

So why isn’t crime easy to control just by locking up these few superoffenders? Let’s examine each example in turn:

Why Can’t Sweden Cut Crime 57% With A Three Strikes Law?

We saw above that 1% of Swedes commit 63% of violent crime in Sweden.

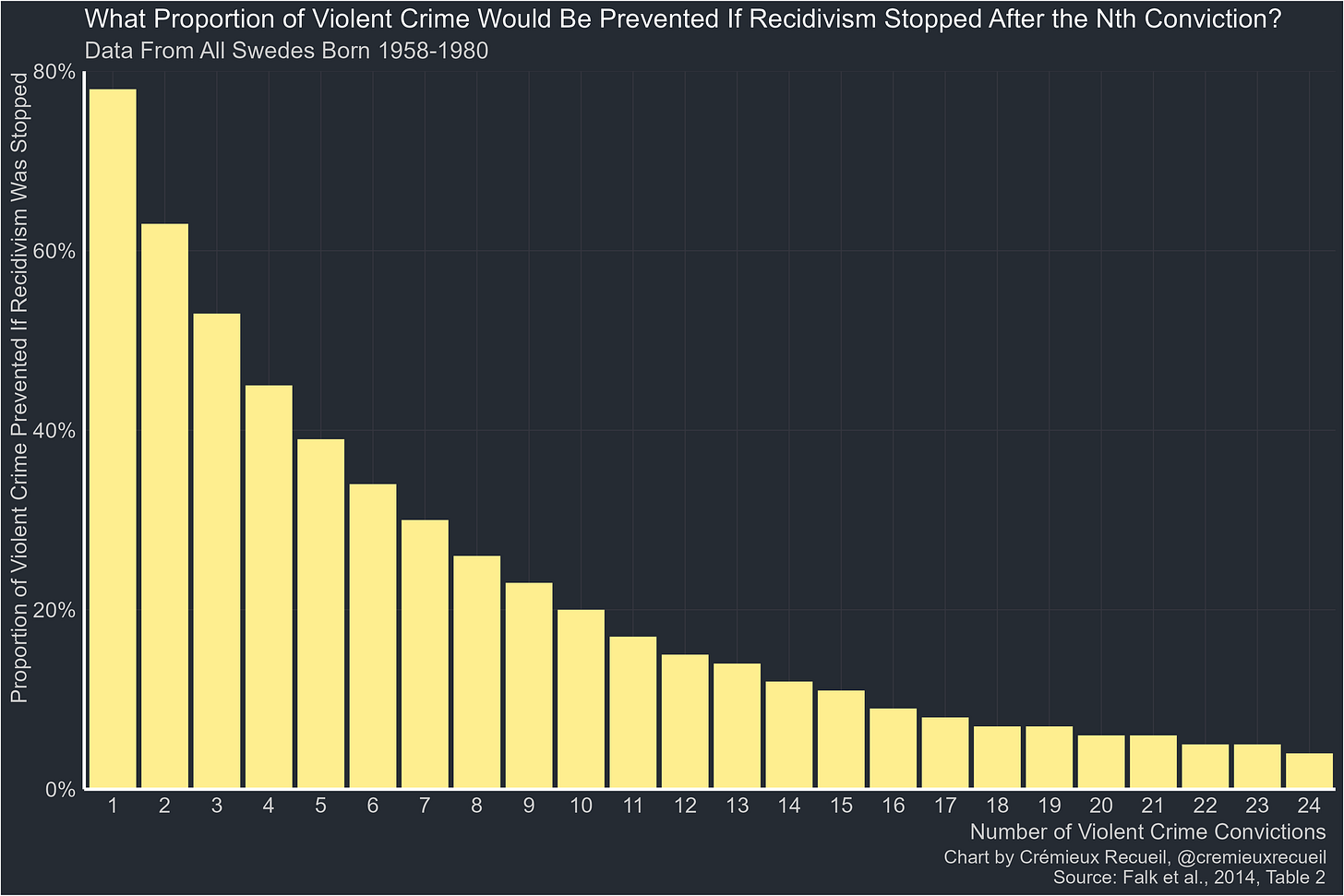

This itself tells us nothing - if we can’t identify that 1% beforehand, nothing can be done. But Cremieux continues the analysis and finds that this superviolent fraction is easily identified by their many past violent arrests:

A one-strike law (life in prison after one violent crime conviction) would cut almost 80% of violent crime in Sweden; a two-strikes law would cut 63%, and a three-strikes law would cut 57%. Even a ten-strikes law would still decrease violent crime by 20%!

So why doesn’t Sweden implement a three-strikes law?

Such a law would add 24,000 people to the Swedish prison system. But the current capacity of the Swedish prison system is only 10,000 people. So this would more than triple the size.

Suppose Sweden only had the resources to expand their prison system by 30%. According to this study, that would cut violent crime by 20%.

I don’t know, these still seem like okay deals to me. But they teach us a useful lesson: there aren’t giant gains to be had by just imprisoning “a few more people”, relative to the size of your existing prison system. Despite the existence of power laws, if you want large decreases in crime, you need large increases in incarceration.

Why Didn’t The Three Strikes Law In California Massively Decrease Crime?

The Swedish data suggested a “three strikes law” should cut crime by 57%. That’s Swedish, and only focuses on violent crime, but American data for all offenses seem to tell a similar story:

A large majority of prisoners - 80% - have been arrested more than three times3.

But in fact, when California passed a Three Strikes law, the decrease was modest:

In the five years following the passage of the law in 1994, crime dropped 33% in California compared to 26% in the rest of the country, meaning only 7% that you could optimistically attribute to Three Strikes. But most criminologists suggest that even this is an overestimate, and the true number is close to zero. See for example this graph, which shows that the counties which used Three Strikes the most had no greater decline in crime than the counties which used it least:

So we expected Three Strikes to decrease crime by 80%, but in fact it decreased it by 0-7%. Why?

Because California’s Three Strikes law was weaker than it sounds: it only applied to a small fraction of criminals with three convictions. Only a few of the most severe crimes (eg armed robberies) were considered “strikes”, and even then, there was a lot of leeway for lenient judges and prosecutors to downgrade charges. Even though ~80% of criminals had been arrested three times or more, only 1-4% of criminals arrested in California were punished under the Three Strikes law.

Why can’t we have a real Three Strikes Law? For the same reason we saw in Sweden earlier. I can’t find any graphs of the US population broken down by number of past offenses, but we know that about 8% of Americans have at least one felony. Let’s say that about half of those have at least three felonies. That means a real Three Strikes law would require increasing the incarceration rate from its current 0.75% up to 4%, ie quintupling it. We’d need to build 6,000 new prisons and 10,000 new jails, locking up an additional 5-10 million people, and spending somewhere between $400 billion and $1 trillion per year (ie around the same as the entire military budget) on prison-related costs. This is light-years outside the Overton Window and I’ve never heard anyone seriously propose it.

Still, it would decrease crime by 80%.

Again, the lesson is that - despite power laws - small increases in incarceration cause small decreases in crime, and only very large increases in incarceration are capable of causing very large decreases in crime.

Why Did A Ten Strikes Law In The Netherlands Massively Decrease Crime?

Given the ambiguous results of three strikes in California, I was surprised to learn that a ten-strikes law in the Netherlands did reduce property crime by 25% (Volaard et al).

In 2001, the Dutch government passed a law allowing longer sentences for criminals with at least ten previous offense who were not good targets for rehabilitation (eg rejected or had already failed drug treatment). The law allowed judges to increase the typical sentence for petty theft (2 months) to a longer sentence (2 years). A quasi-experimental study found that property crime, though not violent crime, decreased by 25%. It’s not surprising that violent crime didn’t go down since the law was almost entirely deployed against thieves.

Vollaard found that the population affected was extremely criminal; they had an average of 31 past offenses, and on surveys they admitted to committing an average of 256 crimes per year (mostly shoplifting). Before the law was passed, they spent an average of four months per year in jail (probably 2 x 2 month sentences); afterwards, they spent two years in jail per crime.

It’s hardly surprising that imprisoning these people decreased crime. So why didn’t the California law do the same?

I think there are two reasons.

First, Europe imprisons far fewer people than any US state. The incarceration rate in the Netherlands is only an eighth that of California. The pre-ten-strikes-law Dutch penalty for shoplifting was two months; the equivalent California penalty alternates between six and thirty-six months depending on which set of propositions won the last election. Vollaard found that the ten strikes law had diminishing returns:

On average, we find the benefits of the policy to exceed the costs by a large margin. We find the benefits to go down rapidly with a more intensive use of the law, however. The marginal crime-reducing effect of convicting another prolific offender to an enhanced prison sentence declines by some 25% when going from the 25th to the 75th percentile in the rate of application of the law during 2001–7. The benefits of the policy remained higher than the costs, however, even for the cities which used the law most intensively.

So I think it’s plausible that California was already much more punitive than the Netherlands even before the California Three Strikes Law was passed, and there were diminishing returns from becoming even more punitive than that.

Second, the California law only applied to certain serious crimes (eg armed robbery). People don’t commit these as often as shoplifting. The average person affected by the Dutch law shoplifted 256 times per year. Even the most energetic criminal would struggle to commit 256 armed robberies per year, and they would probably get killed (or murder a victim) long before reaching that point. So petty theft is longer-tailed than serious felonies, and it’s easier to decrease the petty theft rate by imprisoning the few worst shoplifters compared to decreasing the armed robbery rate by imprisoning the few worst armed robbers.

Why Can’t We Just Incarcerate Those 327 Shoplifters In New York City?

This time we just suck.

Remember, each of these shoplifters was arrested 20 times per year. So they can’t be going to prison in any substantial way. Even if they got a one-month sentence for each arrest, they’d run out of months to shoplift in after twelve!

So the question here isn’t “why are prison sentences for shoplifting so short”, but rather “why can’t New York City incarcerate repeat shoplifters at all?”

I’ll come back to this question later.

What About El Salvador?

They famously solved crime by more imprisonment - how?

By doing a lot of it. I said above that we might be able to decrease US crime rates by 80% if we quintupled our incarceration rate. Between 2014 and today, El Salvador quadrupled their incarceration rate:

They now have by far the highest incarceration rate in the world, 2-3x that of America (which is itself the fifth highest, after various dictatorships). How did they afford this? Through a combination of lots of funding, not being too picky about human rights and prison conditions, and not being too picky about whether the people they imprison were guilty of any specific crime or just kind of gang-adjacent.

As incarceration rate quadrupled, homicide went down by a factor of twenty:

We previously predicted a similar increase in incarceration would lead to an 80% decrease in crime in the US, but El Salvador got a 95% decrease in crime. Why did they do so much better than our prediction? I think because they started with half our incarceration rate and ten times our murder rate. When you’re starting from someplace terrible, without any of the low-hanging fruit picked, it’s easy to make progress!

I can’t find good statistics on other crimes like theft, but the crappy statistics I find say it hasn’t budged (1, 2). Why not? Either my statistics are bad, or the gangs that the government cracked down on weren’t in the theft business.4

Incapacitation

Fine, so despite power laws there’s no way to easily solve crime just by imprisoning a small number of people. How much bang for the buck do we get by incapacitating criminals?

You would think this would be easy to figure out: just determine how many crimes the marginal prisoner commits per year. Then that’s how many crimes incapacitation prevents per year.

But although it’s easy to see how many times the marginal prisoner has been arrested, most crimes don’t result in arrest. How do you know how many crimes they really committed? Some bold scientists have tried asking them - giving prisoners surveys about their criminal histories - but obviously these should be greeted with heavy skepticism.

The method criminologists have settled on is to wait for big shocks to incarceration - big enough to affect the general crime rate - then see how much the crime rate goes up or down.

The best study here is probably Levitt 1996 (you may know Steven Levitt from Freakonomics). In the 1970s, US prisons were overcrowded. The ACLU argued the overcrowding was a rights violation - a form of “cruel and unusual punishment” - and sued a dozen states. They won all their lawsuits, and judges in all states said the government had to free prisoners until prison crowding returned to a non-cruel, usual level. So at a slightly different time in each state, many prisoners got released all at once. By examining the effects of this sudden release on the crime rate, we can determine how much crime the incarceration of those prisoners was preventing.

Levitt does a lot of fancy statistics, and Roodman reanalyzes with even more fancy statistics, but the good news is they both agree and get numbers somewhat contrary to Roodman’s biases, which make me trust them more. Each year of imprisoning the type of prisoner who got released under the ACLU lawsuits prevented 6 property crimes and 1 violent crime. This suggests the average criminal commits ~7 crimes per year, which I think matches well with the data above showing that the median prisoner has 10 past arrests and some have 30+.

Other studies on incapacitation, mostly taken from Roodman, that I trust less than Levitt:

Owens (2009) investigated a Maryland law that caused some criminals to get released early. They found a crime increase corresponding to about 3 crimes per prisoner per year. This is lower than Levitt’s estimate of 7, but crime rates went down in general between Levitt’s study period (the 70s) and Owens’ (the 2000s), so they might both be right.

Buonanno and Raphael (2013) investigate the same Italian mass pardon that we discussed earlier. They found a crime increase corresponding to about 18 crimes per year. This is higher than Levitt’s estimate of 7. But Italy has a lower incarceration rate than the US, potentially meaning that the average criminal they incarcerate is worse, so they still might both be right.

Lofstrom and Raphael (2016) look at a California law that decreased prison overcrowding by releasing many inmates early. There is a lot of debate over this, but one common conclusion (also supported by Roodman’s reanalysis) is that it caused 3 crimes/prisoner/year, which is less than Levitt’s for probably the same reason as Owens.

All of these only measure reported crimes. A common rule of thumb is that only 40% of crimes get reported. Once we adjust for this effect, we estimate that the average criminal who gets released from prison commits between 7 (Owens, Lofstrom) and 17 (Levitt) crimes per year. I’ll be using the 7 number as the headline result later, since it’s backed by more studies and more recent5.

All studies agree that these are mostly smaller property crimes (eg shoplifting and car theft). This easily believable, since these are the large majority of all crimes in any situation.

I didn’t go too deep into this, incapacitation doesn’t have to mean prison. Some types of probation can be effective forms of incapacitation, especially if they involve (eg) GPS monitoring. A more comprehensive look at the costs vs. benefits of prison would go deeper into whether intensive probation is an acceptable substitute - something I’m not going to do here.

Aftereffects

We examined deterrence - the effect of strict sentences on crime before imprisonment. We examined incapacitation - the effect of strict sentences on crime during imprisonment. Now we come to the effect of strict sentences on crime after imprisonment.

An optimistic school of thought hopes that stricter sentences will decrease crime after release. After all, the longer you’re in prison, the longer you have to be scared straight, or find God, or get rehabilitated.

A pessimistic school of thought suspects that stricter sentences will increase crime after release. I find this one more plausible6.

Take a moment to imagine how your own life would change if you spent ten years in prison. Seriously, spend a literal few seconds thinking about your specific, personal life.

Maybe when you get out of prison, you’ve long since lost your job and your house/apartment. Whatever career skills you once had are ten years obsolete - but it won’t matter, because your industry does background checks and won’t hire convicted felons. You can’t move to an area with better economic prospects, because you have to check in with your parole officer once a week.

Your partner has long since filed for divorce and is happily remarried to someone else. Your kids have long since moved on; if they remember your name at all, it’s as “that guy who was never there for us”. All of your friends have drifted away, forgotten you, or have nothing in common with you anymore.

You try to get food stamps, but (in some states) felons are banned from getting welfare. You try to get Section 8, but (in some states) felons are banned from getting public housing.7

So what do you do? In prison, you probably met and talked with a wide variety of hardened criminals - shoplifters, burglars, bank robbers, drug dealers, counterfeiters - who told you stories about their lives and taught you tips of the trade. You might have joined a gang in prison, and they might have an outside-of-prison chapter willing to take care of members and get them set up with good positions in their criminal network.

Given a situation like this - no family or friends, no legal prospects, immersion in a social network of criminals, and good connections to the criminal lifestyle - it’s a miracle every time a new release doesn’t return to crime.

As usual, miracles are rare. The data show that 43% of people released from prison are re-arrested within one year, and 82% within ten. But this on its own doesn’t tell us whether they were already destined to become serial criminals, or whether prison itself increased their likelihood of recidivism. We can divide this into two sub-questions:

How does any prison term at all, as opposed to staying free, change one’s chance of being re-arrested?

How does a longer prison term, as opposed to a shorter prison term, change one’s chance of being re-arrested?

Unfortunately, these will be the most difficult and controversial questions we’ve encountered thus far.

Even worse, we can’t escape answering them. If aftereffects are beneficial or neutral, then the beneficial effects of incapacitation win out, and prison is net good for preventing crime. Only if aftereffects are detrimental, and their magnitude is great enough to cancel out the benefits of incapacitation, can prison be net neutral or net negative for crime.

As far as I can tell, most criminologists are confused on this point. They’re going to claim that the sign of aftereffects is around zero, or hard to measure - then triumphantly announce that they’ve proven prison doesn’t prevent crime.

The only pro-shorter-sentences researcher who is actually thinking clearly about this is Roodman. He will argue that aftereffects are harmful, and that the best studies suggest their magnitude is around the same as the benefits of incapacitation - so that they more or less cancel out. His argument is logically valid, which tragically forces us to actually look at the evidence and see if he’s right.

Question 1: How Does Any Prison Term At All Change The Chance Of Being Rearrested?

The largest and most recent meta-analysis of this question is Petrich (2021). They analyze 116 studies and take a strong stand, saying:

Beginning in the 1970s, the United States began an experiment in mass imprisonment. Supporters argued that harsh punishments such as imprisonment reduce crime by deterring inmates from reoffending. Skeptics argued that imprisonment may have a criminogenic effect. The skeptics were right. Previous narrative reviews and meta-analyses concluded that the overall effect of imprisonment is null. Based on a much larger meta-analysis of 116 studies, the current analysis shows that custodial sanctions have no effect on reoffending or slightly increase it when compared with the effects of noncustodial sanctions such as probation. This finding is robust regardless of variations in methodological rigor, types of sanctions examined, and sociodemographic characteristics of samples. All sophisticated assessments of the research have independently reached the same conclusion. The null effect of custodial compared with noncustodial sanctions is considered a “criminological fact.” Incarceration cannot be justified on the grounds it affords public safety by decreasing recidivism. Prisons are unlikely to reduce reoffending unless they can be transformed into people-changing institutions on the basis of available evidence on what works organizationally to reform offenders.

Again, Petrich seems to think that, having proven aftereffects “have no effect on reoffending or slightly increase it”, he’s triumphantly proven prison doesn’t work. But in order to really prove that, he’d have to demonstrate that aftereffects’ tendency to “slightly increase” reoffending is large enough to neutralize prison’s positive incapacitative effects. So let’s look further at the effect size.

The effect size statistic here is r, representing the correlation coefficient between a dummy variable where noncustodial sanctions are 0 and custodial sanctions are 1, and likelihood of reoffending. But later they give a better explanation, saying that:

A mean correlation of approximately .080 translates into an 8 percentage point difference in reoffending between those sentenced to custodial and noncustodial sanctions (Bonta and Andrews 2017; see also Randolph and Edmondson 2005). Thus, assuming that 46 percent of the comparison (noncustodial) group reoffended, the percent reoffending in the custodial sanction group would be 54 percent.

How do we translate this into number of crimes? They don’t tell us, but here’s my extremely sketchy hand-wavey suggestion: let’s imagine this is recidivism rate over one year. We know that 43% of prisoners usually reoffend during this time, so if we believe these data, 35% of similar offenders who got noncustodial sanctions would. That means they offend about 20% less. Although we absolutely cannot do this and we’re assuming all sorts of completely false things about how distributions work, let’s imagine this means the average person in this category commits 20% fewer crimes. That would mean that, if prisoners commit 10 crimes/year after release, the same people, given a noncustodial sentence, would commit 8 crimes/year.

In order to neutralize the effect of one year imprisonment (-10 crimes), the negative effects of incarceration (+2 crimes/year) would have to continue for five years. But they probably won’t, because we know that most of these people get rearrested sooner than that anyway.

So I think that at this level, it’s hard to conclude that aftereffects cause more crime than incapacitation prevents.

What does Roodman - whose argument hinges on the claim that they do - say about this? He doesn’t separate out the custodial/noncustodial question from the sentence length question, so we’ll look at his arguments more in the next few sections.

Question 2: How Do Long Vs. Short Prison Terms Change The Chance Of Being Rearrested?

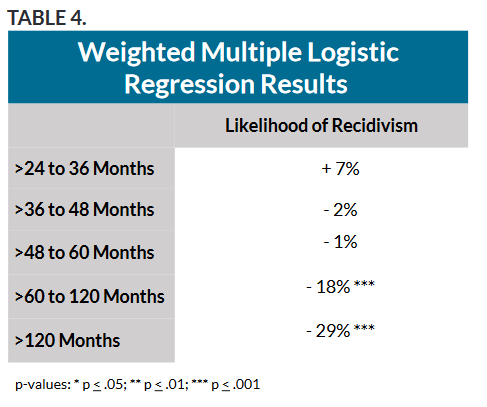

We’ll follow our usual pattern of looking at one study in depth and then racing through the others. Our deep study will be the National Sentencing Commission’s report on Length Of Incarceration And Recidivism, because it’s the most official-sounding. They examine 32,125 offenders and compare them to “matched control” offenders who got different sentence lengths to see which group reoffends more often. Here are their results (numbers represent how much more likely the group with longer sentences was to reoffend):

So we see that among prisoners with short sentences, longer sentences don’t significantly increase or decrease recidivism. If we’re willing to look at nonsignificant results, then in the shortest-sentence group (<3 years), increasing the sentence increases recidivism, zeroing out by about 5 years, and then as sentences get increasingly longer than five years, longer sentences = less recidivism.

I think this actually makes sense. A very short prison sentence (eg one day) doesn’t ruin your life. As the sentence lengthens, your life gets more and more ruined, as all the tragedies we talked about earlier - job loss, career obsolescence, partner divorce, friends drifting away, etc - start to come into play. But after five years, it maxes out - your life is as ruined as it can possibly get. So after that, increasing time in prison can only have positive effects (eg making you more convinced that crime is bad and that you don’t want another super-long prison sentence).

My only concern about this finding is age. All research agrees on the absolutely crucial role of the age-crime curve:

People take various policy implications from this (maybe “life sentences” should end at 65, since incapacitation is unlikely to help much after that). But here we’re interested in its potential to confound studies. A 20 year old who gets 5 years in prison is released at 25 - still young! - but a 20 year old who gets 10 years in prison is released at 30 - too old to be leaping on rooftops and running from cops. The National Sentencing Commission understands this problem, and matches the experimental and control groups by age at release. But this introduces a new bias - now they’re different ages when they start committing crimes. Might a person who starts crime at 15 be a more disturbed and committed criminal than one who starts at 20? Seems plausible. I think this might be responsible for a lot of the seemingly positive effect of sentences > 5 years.

There are dozens of other studies on this topic, all hotly debated, so even in this part I’m only going to list a few highlights. Still, these are:

Green and Winik (2010). They use random judge assignment, ie look at criminals with similar crimes who got lenient/strict judges and so shorter/longer sentences. They find that the total difference in rearrests is indistinguishable from zero. But the length of time in which they were measuring rearrests includes the time the offenders were in jail, so this is saying that incapacitation plus aftereffects was zero (plus or minus a margin of error), meaning that aftereffects must be detrimental and large enough to cancel out the benefits of incapacitation, just as Roodman claims.

But this study looked at minor crimes where sentences were measured in months, so I think this matches our previous suspicion that aftereffects might be detrimental in short sentences but neutral-to-beneficial in longer ones.

Roach and Schanzenbach (2015) More random judge assignment, this time in Seattle. They find that each month of longer sentence decreases future reoffending by one percentage point. Most of these sentences are short, so this contradicts our working theory that lengthening short sentences increases crime but lengthening long ones decreases it. Neither Berger nor Roodman really want to take this study too seriously; Berger objects that it’s an unusual study population (everyone entered a guilty plea), and Roodman objects that the judge selection might not have been truly random.

Rhodes (2018) is a matching study - it artificially tries to create groups of prisoners who are as similar as possible except that one group got longer sentences. Its big advantage is that it has some people serving moderately long sentences (a few years), getting us out of the few-month range investigated by some of the other studies. It finds a mild beneficial effect of longer sentences:

This study provides no evidence that an offender’s criminal trajectory is negatively affected – that is, that criminal behavior is accelerated – by the length of an offender’s prison term. If anything, longer prison terms modestly reduce rates of recidivism beyond what is attributable to incapacitation. This “treatment effect” of a longer period of incarceration is small. The three-year base rate of 20% recidivism is reduced to 18.7% when prison length of stay increases by an average of 5.4 months. We are inclined to characterize this as a benign, close to neutral effect on recidivism.

What Do Our Experts Think?

As mentioned above, these are only a few of the very many studies on this topic, and I’ve only given the briefest summary of each. Due to the complexity of this literature, I’m relying more than usual on the opinion of the expert reviewers.

Berger (pro-longer-sentences) says:

Considering the rigorous research published since the Nagin et al. (2009) review, the literature regarding length of stay on recidivism is still somewhat inconsistent, with many studies claiming no recidivism effects and some showing that increased prison length reduces recidivism slightly. However, just like the rest of the research examined thus far, the study methodologies vary in terms of their limitations, which could explain some of the mixed results [...] At present, there is no substantial evidence that a criminogenic effect exists in the aggregate. Thus, it remains unclear whether criminogenic effects exist, and if so, under what circumstances...Among the substantial number of published studies with varying methodologies, not one has found a large aggregate-level criminogenic effect.

Roodman (pro-shorter-sentences) says:

The preponderance of the evidence says that incarceration in the US increases crime post-release, and enough over the long run to offset incapacitation. A quartet of judge randomization studies (Green and Winik in Washington, DC; Loeffler in Chicago; Nagin and Snodgrass in Pennsylvania; Dobbie, Goldin, and Yang in Philadelphia and Miami) put the net of incapacitation and incarceration aftereffects at about zero. In parallel, Chen and Shapiro find that harsher prison conditions—making for incarceration that is harsher in quality rather than quantity—also increases recidivism. Gaes and Camp concur, though less convincingly because in their study harsher incarceration quality went hand in hand with lower incarceration quantity. Mueller-Smith sides with all these studies and goes farther, finding modest incapacitation and powerful, harmful aftereffects in Houston; but modest hints of randomization failure accompany those results.

Some studies dissent from the majority view that incarceration is criminogenic. Roach and Schanzenbach find beneficial aftereffects in Seattle—a result that is also subject to some doubt about the quality of randomization. Bhuller et al. make a more compelling case that incarceration reduces crime after—in Norway. Berecochea and Jaman, one of the few truly randomized studies in this literature, also looks more likely right than wrong, and is also somewhat distant in its setting, early-1970s California. And there are the two Georgia studies, which upon reanalysis no longer point to beneficial aftereffects, but still do not demonstrate harmful ones either.

Aftereffects must vary by place, time, and person. But the first-order generalization that best fits the credible evidence is that at the margin in the US today, aftereffects offset in the long run what incapacitation does in the short run.

Nagin (neutral, tie-breaker) says:

Compared with noncustodial sanctions, incarceration appears to have a null or mildly criminogenic effect on future criminal behavior. This conclusion is not sufficiently firm to guide policy generally, though it casts doubt on claims that imprisonment has strong specific deterrent effects.

What conclusions do we draw from these studies of the dose-response relationship between time served and reoffending? The one experimental study is suggestive of a preventive effect, but that effect may be attributable to incapacitation. Two of the matching studies point weakly to a criminogenic type dose-response relationship, but both are extremely dated. The Loughran et al. (2008) study suggests a possible criminogenic effect of placement but finds no linkage between time served and reoffending. We draw no conclusions from the results of the regression studies. Not only are results extremely varied, but more importantly all of the studies suffer from a fundamental analytical flaw. This flaw relates to the potential sensitivity of regression- based studies to specification errors in the model of the relationship of age and offending rate.

In other words: Berger and Nagin think evidence is weak and it’s kind of a wash and maybe there are slight criminogenic effects; Roodman thinks there are strong criminogenic effects that (on the current margin) are sizeable enough to approximately cancel out the benefit from incapacitation.

So What’s Up With Roodman?

At the risk of repeating myself: this is the question upon which this whole essay hinges.

Everyone agrees that the beneficial effects of deterrence are real but small.

Everyone agrees that the beneficial effects of incapacitation are real and large.

Everyone except Roodman agrees that aftereffects range from slightly beneficial to slightly detrimental, for a net effect of incarceration significantly decreasing crime.

Only Roodman says that aftereffects are large and detrimental, for a net effect of incarceration having no effect on crime.

So where does Roodman disagree with everyone else?

My impression is that the main difference is that Roodman gives more weight to certain judge selection studies. These find that being randomly assigned to a lenient vs. strict judge (and therefore on average getting a short vs. long sentence) doesn’t change rearrest rates after X years from the time the sentence started. This X year period includes both the time spent serving the sentence, and the time after release when aftereffects might materialize - ie they include both incapacitation and aftereffects. Since these studies fail to find any net effect, and incapacitation effects must be beneficial and large, Roodman concludes that aftereffects must be detrimental and large.

Then he reanalyzes several of the other studies that other people use to demonstrate no or beneficial aftereffects, and finds them less convincing after reanalysis.

So who is right?

Roodman gets his strongest evidence from studies of short sentences vs. shorter sentences (eg going from 0 to 1 years, or 1 to. 2 years). These are naturally where we would expect the fewest benefits from incapacitation. But they’re also where we would common-sensically expect the worst aftereffects. Someone going from zero prison to one year in prison has had their life, career, and relationships profoundly changed, in a way that someone going from ten years in prison to eleven years hasn’t.

This is consistent with the National Sentencing Commission study above. They found that aftereffects trended worse the shorter the sentences got, but didn’t investigate any sentences shorter than 2-3 years. If the trend continues, sentences shorter than that could have aftereffects > incapacitation.

So maybe Roodman is right about shorter sentences, and everyone else is right about longer sentences. Going from a month to a year in prison is so disruptive and criminogenic that it risks canceling the benefits of eleven extra months of incapacitation. But going from ten years to eleven years mostly just gives you the incapacitation.

Marginal Revolution

This highlights a problem with all of these studies: we can only talk about particular margins.

Imagine a country which currently incarcerates zero people, trying to decide whether to move up to a policy of incarcerating one person. If you only incarcerate one person, it will be the baddest dude in the whole country. That guy really needs to be behind bars! And we’re not worried about turning him into a hardened criminal, because he’s already maximally bad. Here it’s obvious that benefits outweigh costs.

Now imagine a country which incarcerates 50% of its population, trying to decide whether to move up to 50% + 1. At this point, you’re imprisoning someone who went a few miles over the speed limit. You gain no benefits from incapacitation (he wasn’t going to commit any crimes anyway), but you stand to lose a lot from aftereffects (he’s probably a totally normal law-abiding citizen, so there’s a very high risk of ruining his life and turning him into a more hardened criminal). Here it’s obvious that costs outweigh benefits.

So the question isn’t “do the costs of prison outweigh benefits?”, but rather “at what point between incarcerating 0% and 50% of people does the cost of imprisoning one more person start outweighing the benefits?”, or even “at the current US incarceration rate of 0.75%, does the cost of imprisoning one more person outweigh the benefits?”

In some sense, this is what we’ve been investigating the whole time - all of these studies are being conducted at the current margin. But this hides big differences between them.

We’ve already seen that European studies get stronger results than American studies. That’s because European countries have incarceration rates of ~0.05%, compared to America’s ~0.75%. In theory, Europeans countries’ incarceration rates are lower because they have less crime. But I notice that the European countries we’re talking about here all have high recent new immigrant populations, and in Europe these groups commit more crimes per person than natives. So it’s possible that Europe is still adjusting to being a high-crime continent, whereas America has already adjusted by raising incarceration rates. So one possible conclusion is that the benefits of incarceration strongly outweigh costs in Europe. I think this is clearly true by American values - we seem to care more about preventing crime, and be less horrified by imprisonment, than the average European.

But there are many different margins even within America. Louisiana’s incarceration rate is >1%; Massachusetts is <0.25%. Some of the variance reflects the criminality of each state’s population, but other variance reflects the values of each state’s voters and policy-makers. We haven’t been keeping great track of which state each of our studies comes from, but plausibly the marginal prisoner in Massachusetts is a badder dude than the marginal prisoner in Louisiana, and releasing him is more likely to have costs > benefits.

Margins also differ across eras. US incarceration ranged from 0.2% in 1970 to 0.95% in 2007 to about 0.75% today. Our studies cover this entire time period. This is probably why Levitt found stronger incapacitation effects (studying the 1970s) than Owens or Lofstrom+Raphael (studying the 2000s).

Finally, there are the margins across sentences we discussed earlier. Going from zero years in prison to one year is a bigger deal than going from ten to eleven.

When we examine our original question - does extending the average prisoner’s sentence for one year substantially decrease crime, we find that there’s no single answer - it depends where we are on all of these margins. Roodman’s skeptical position is most plausible for shorter sentences in high-incarceration areas, and Berger’s pro-prison position is most plausible for longer sentences in low-incarceration areas.

So Why Do People Keep Saying That Prison Doesn’t Decrease Crime?

We began with the observation that criminologists tend to deny that prison decreases crime. We now know why Roodman thinks this: he idiosyncratically believes that aftereffects equal (and so cancel out) incapacitation. But nobody else has even gotten this far. So what’s everyone else’s position?

The Vera Institute is an anti-incarceration think tank. They have a policy paper titled The Incarceration Myth: More Incarceration Will Not Decrease Crime. It says:

There is a very weak relationship between higher incarceration rates and lower crime rates. Although studies differ somewhat, most of the literature shows that between 1980 and 2000, each 10 percent increase in incarceration rates was associated with just a 2 to 4 percent lower crime rate.

This is just taking the (real, positive) effect of incarceration on crime, and calling it “very weak”.

Research shows that each additional increase in incarceration rates will be associated with a smaller and smaller reduction in crime rates.

We saw above that this is true, but I find it annoying to mention here in this kind of advocacy context - it’s also true of everything else in the world! When the Vera Institute publishes anti-mass-incarceration white papers, the 500th white paper will be less influential than the first. If I claimed that “research showed” this, and so they should stop publishing anti-mass-incarceration white papers, they would look at me like I’d gone insane. Get a life.

The weak association between higher incarceration rates and lower crime rates applies almost entirely to property crime. Research consistently shows that higher incarceration rates are not associated with lower violent crime rates.

This is sort of true. Research finds a stronger effect of incarceration on property crimes than violent crimes, although Levitt does find a violent crime effect of minus one violent crime per incarceration-year. Partly this is because violent crimes are rarer than property crimes, and so studies are underpowered to find them. And partly it’s because most studies are done on mass releases of prisoners, where (for example) the state has to release 25% of the prison population to decrease overcrowding, but they get to choose which 25% - and states are smart enough not to release the murderers and psychos. Still, if Vera Institute’s preferred decarceration policy is also smart, then it won’t release the murderers and psychos either, and this point will stand.

So my interpretation of Vera Institute is that they’re making some good points about ways that incarceration isn’t an infinitely powerful cure-all, but that it’s deceptive to summarize them as “incarceration doesn’t decrease crime”.

What about other groups? Prison Policy Institute has a list of “crime myths”. Myth #7 is that “Harsh punishments deter crime, making us safer”. They write:

Many people mistakenly believe that long sentences, paired with austere and even brutal prison conditions, will have a deterrent effect on crime. But research has consistently found that harsher sentences do not serve as effective “examples” that would prevent new people from committing serious crimes. In 2016, the National Institute of Justice summarized the research on deterrence, finding that prison sentences, and especially long sentences, do little to deter future crime

Here they’re using “deterrence” in the strict sense (that is, in a way that doesn’t count incapacitation), noting that it’s small, and rounding off “small” to “zero”.

I’ve looked at some other sites and think tanks that claim to have arguments against the “myth” that prison prevents crime, and they’re all using these same two tricks. Either they ignore incapacitation and focus only on deterrence + aftereffects. Or they imagine some hypothetical prison super-fan who believes that incapacitation is infinitely effective, prove that it’s less effective than this, declare victory over this fake opponent, and then summarize their win as “prison has no effect”.

What Are The Costs Vs. Benefits Of Prison?

So a more honest version of the claim that “prison has no effect on crime” might be “the effect of prison on crime is weak”. How weak is it?

We already saw one way to answer this: it probably prevents on average 7 crimes/year (6 property + 1 violent), minus some amount, especially for short sentences, if you believe in criminogenic aftereffects. For the shortest sentences at the highest-incarceration margins, it’s possible for the effect to be zero or less.

Another way to answer is with elasticities. If we increase in incarceration rate 10%, how much crime do we prevent at the current margins? Levitt estimates 3%, Cohen finds 0.5-7%, and Dhodnt finds -2% (ie prison increases crime) but this is an outlier.

Spelman writes:

Our best estimate of elasticity is “in the neighborhood of [3% drop in crime per 10% increase in incarceration]” but “[a]ny figure between [2% and 4%] can be defended, and we should not be too surprised to find that the result is anywhere between [1% and 5%]”

This broadly agrees with our numbers from Sweden, California, and El Salvador above. Small increases in incarceration cause small decreases in crime. Large increases in incarceration cause large decreases in crime. If you doubled the incarceration rate, locking up an extra million people, then crime would decrease ~30% at current US margins (maybe less, because you’re shifting the margin and getting diminishing returns).

Would more prison be good or bad? We’d need to do a cost-benefit analysis. Surprisingly, Roodman does the best work here: after making his claim that costs and benefits mostly cancel out, he admits that most people won’t believe him, and tries to estimate the effect size in the “devil’s advocate” case where everyone else is right and he is wrong.

He starts with our previous finding that incapacitation prevents ~7 crimes a year, and returns to the incapacitation studies to see what types of crime are most affected. Then he adjusts for the low level of aftereffects that everyone else believes in. I’ve redone his results for clarity. This table shows the total number of each type of crime prevented by keeping the marginal prisoner in jail for one extra year:

If we’re trying to calculate the costs vs. benefits of imprisonment, we need to put a cost on all these crimes. This is hard to quantify - a robber may steal $100 worth of goods, but valuing his crime at $100 in costs ignores the disutility of (eg) living in fear

Roodman uses two methods: first, he values a crime at the average damages that courts award to victims, including emotional damages. Second, he values it at what people will pay - how much money would you accept to get assaulted one extra time in your life?

These estimates still exclude some intangible costs, like the cost of living in a crime-ridden community, but it’s the best we can do for now. Here are his answers (I’ve taken the geometric mean of the two methods):

So one extra year of incarcerating the marginal criminal saves society $44,000 in crimes prevented.

Now we add in the opposite side of the ledger: the costs of incarceration:

According to Roodman, the average prisoner costs the state $31,000 per year. He got his data from 2008, and it’s since ballooned to about $60,000, but we’ll keep his number so that everything is from the same time period.

(also, as always, California is more expensive - here it’s $120,000)

Roodman also adds in the costs to the prisoner. He uses some surveys to value the disutility of the suffering caused by a year in prison at $50,000; additionally, the prisoner loses about $16,000 in earning potential.

The end result: if you don’t count the costs to the prisoner themselves, and you don’t use the more modern number, and you’re not in an expensive state like California, then the marginal incarceration-year saves society about $13,000.

If you do count those things, or you’re in an expensive state, the costs far outweigh the benefits.

Realistically, most people won’t care about analyses like this. They’ll be more interested in the unquantifiable costs and benefits, including:

The “benefit” of feeling like justice has been done and an evil deed has been avenged.

The “cost” of becoming the type of person who puts their fellow humans in cages.

The beneficial effects on non-crime forms of public disorder - the prisoner can no longer litter or harass people on the subway.

The cost of within-prison crimes. Even if you dismiss the suffering of a prisoner caused by prison itself (on the grounds that justice demands it), prisoners getting raped or shanked was not part of their sentence and should plausibly get counted on the debits side of the ledger.

The cost to innocents. Nobody knows what percent of prisoners are innocent, but I have seen estimates from 2 - 5%. Even if you dismiss the suffering of a guilty prisoner, you probably don’t want to dismiss the suffering of an innocent one.

The benefit from increased urban density. Ben Southwood claims that this may outweigh all other costs and benefits in the equation. His argument goes: when cities are crime-ridden, people move to the suburbs. The suburbs are less dense than cities, driving up housing costs and decreasing the agglomeration effects crucial for technoeconomic progress. Therefore, crime is responsible for a significant portion of the housing crisis and of lost GDP from the Great Stagnation.

The cost of imprisonment to families and communities - for example, now the prisoner’s children are without a father, the prisoner’s family is without a son/brother/etc, the prisoner’s corner store is without a customer, etc.

Although we can’t quantify these, pro-longer-sentencing people note that when you survey the poor minority communities most affected both by crime and by mass incarceration, they tend to say they want the government to be tougher on crime. This suggests that at least some of the unquantifiable benefits outweigh the unquantifiable costs.

Even if we’re not going to swallow the result whole, I think these kinds of analyses help us understand what we’re really getting per extra incarceration-year. For about $30,000 - $120,000 in imprisonment costs, we’re getting four fewer shopliftings, two fewer car thefts, and a small decrease in violent crime.

Long Prison Sentences Are Probably One Of The Least Cost-Effective Ways To Reduce Crime

This paper estimates that an extra police officer prevents about 20 crimes per year. This is true prevention, not incapacitation (ie the officer’s presence deters criminals from acting, rather than catching them afterwards).

We previously said an extra year of incarceration averts 7 crimes. But the 20 crimes from police and 7 crimes from incarceration aren’t directly comparable, because the 20 is reported crimes and the 7 is total crimes. Only about 40% of crimes are reported, so we expect that the police officer really prevents about 50 total crimes.

A year in prison costs $60,000 (ignoring costs to the prisoner themselves). An extra police officer costs $150,000.

So prison prevents one crime per $8,500 spent, and police prevent one crime per $3,000 spent. This looks even better once we adjust for the moral cost of prison: the cop is three times as cost-effective without locking someone in a cage for a year!

So What Do We Do About Shoplifting In California?

This post was somewhat motivated by an earlier guest post on California’s Proposition 36, which argued that lengthening prison sentences for shoplifters wasn’t the right tool to fight shoplifting. The comment section was pretty hostile to this thesis and refused to believe it. Now that we know more, let’s look at this question again.

…and it’s not clear that anything we’ve learned bears on this question at all.

We said before that 327 shoplifters in New York City were responsible for a third of the city’s petty theft, and that each of them gets arrested twenty times per year. A similar group of Dutch offenders shoplifted 256 times per year.

Proposition 36 increased sentences for shoplifting from six months to three years. But it doesn’t seem like these shoplifters are getting six months or three years. It doesn’t seem like they’re even being arrested. If they are, they’re either being let off without penalty, or - at most - in jail for a few days.

So for me, the interesting question isn’t “should jail sentences be short or long?”, but rather why we can’t punish repeat shoplifters at all, with short sentences or long sentences.

I asked the comments section this question, and got some good responses from people with criminal justice experience:

Graham (ex-cop) says:

Police have limited time and resources, they they focus - individually and at the department level - on the priorities that the voters and elected officials set for them. When elected officials say “the punishment for crime X is a stern talking to” the police get the message: crime X is not important. That’s why we don’t use undercover sting operations to apprehend jaywalkers.

That is what has happened with theft in California. Police are not - and should not - waste time hunting down and arresting thieves who will be immediately released, which is the current regimes. For some reason the author thinks police should commit time and resources to arresting people who will not even be booked into jail and/or will be immediately released.

So apparently the police aren’t arresting these people because the attorneys aren’t punishing them. What do the attorneys have to say for themselves?

Andrew Esposito (ex public defender) says:

[Graham] doesn't actually know what he is talking about.

Evidence on this topic shows pretty clearly that arresting someone for misdemeanor larceny and then letting them go actually does a good job of preventing them from shoplifting in the future. If the police are saying "what's the point of arresting because they'll just let them go" then they are severly mistaken. In addition, almost every state regime has escalating punishments based on records. This could look like a three strikes law (your third misdemeanor larceny conviction becomes a felony) or alternatively handled at sentencing, where a judge, when deciding what punishment is appropriate, chooses to give harsher sentences to those who have comitted the crime before. In either case, you still want to be arresting even first time offenders who will receive a slap on the wrist, because when you arrest them the second or third times they will no longer be wrist slapped, but locked up for increasingly long stints. In my own jurisidiction, first offense petit larcenies were handled with community service, second offense was a weekend in jail, third offense was 10 days in jail, and then after that you'd be looking at serious time on the order of months, and eventually years. It should be (possibly weak) evidence of the system working that the vast majority of the theft cases that came through our office were first time offenders, not career thieves. Once someone gets caught, arrested and has to go through a trial, it suddenly doesn't seem worth it to steal shirts from target, or a steak from Kroger. My personal take is you want a system where the chances of being caught are very high, but then the punishments are relatively modest (but high enough to make it not monetarily worth it to steal).

And CJW says:

I was a municipal prosecutor for 10 years, a county one for 17, and a public defender for 4 […]

In municipal court what would happen is they get a ticket, some cop has to write up a VERY brief probable cause affidavit but I would guess it still took an hour for the paperwork, I spend 5 minutes reviewing it and sign off on it. If the defendant doesn't show, they get a bench warrant, with a bond equal to the fine, say $200 first offense (plus cost of lost goods if not recovered). They get stopped for a ticket someday, and end up paying the bench warrant bond off to avoid jail, or they don't have that money in which case they sit in jail about a day before the municipal judge releases them because county jails don't have space to hold shoplifters for days and it costs like $40/day per inmate for the city to have them housed there. I would say only 1/100 cases would the defendant show up, demand a trial, and require me to get the loss prevention manager of Wal Mart to show up for night court.

If it was a repeat offender, it might get referred to county, where the typical disposition might be 90 days jail suspended (it would be imposed only if they broke probation), with 2 yrs of unsupervised probation. Because I was both the municipal prosecutor and county prosecutor, I could actually control this a little and would cherry pick the cases out of municipal that I thought needed to go higher. (And sometimes in the other direction to cut somebody a break.) But if that had not been the case, there wouldn't be any coordination there and no rhyme or reason as to why some cases had a $200 fine and some had 2 yr bench probation period and real chance of jail.

Over $750 it was a felony, which was a different matter. If a stealing victim was a private citizen these nearly always remained felonies. On a shoplifting, there was some chance it would get reduced to a misdemeanor. If property was unrecovered the person could make restitution in advance they had a better show of this.

The reason mandatory jail doesn't work (and this applies to more than shoplifting) is that if you tell people they're going to jail, you have to give them a public defender. They are also less likely to want to plead guilty, and more likely to want a trial, or at least drag it out towards trial. In a regime where there is prosecutorial discretion, as I had, what will inevitably happen is that the state will face down an organized push from the local public defenders' office to set a bunch of shoplifting cases for jury trial. They know the state won't want to have those trials, and probably doesn't have the courtroom dates available to do so. And if you go ahead and call the bluff and try them, the odds are that the sentence the defendant gets won't be bad enough to deter this maneuver -- judges aren't supposed to increase sentences just because a guy chose to have a trial, so it's still unlikely he'd get more than whatever the mandatory minimum was set at. So the prosecutors will do the only remaining thing they can, which is amend the charge down to something that doesn't carry the mandatory minimum, thus allowing them to unclog the system.

Theodidactus writes:

Hello. Criminal defense attorney here.

As I said on a previous post of yours, I don't think the tough on crime crowd realizes how many resources the US system is *obligated* to spend in the case of a criminal prosecution (and you can't have jail or prison without a criminal prosecution).

If you charge someone with shoplifting and insist on 30 days in jail, the defendant can obligate the system to provide

- a lawyer

- a jury of 6 (in minnesota) or 12 (if you're going to impose prison time)

- a judge

- a court reporter

- a prosecutor

- a cop witness

...several of these for multiple hearings (you'll appear before a judge using your lawyer several times in the course of a criminal case)

additionally, that same defendant can obligate the *victim* to provide

- footage of the incident

- a store witness

all for a $5 pack of hamburger patty (yes, I have seen a shoplifting trial on a $5 pack of hamburger patty)

...and at the end of all this, even if the conviction sticks, you still have to sell a judge on sending some poor guy to jail for *thirty days*. Not that it can't happen, but it's such an immense expense of time and effort for everyone involved that it's usually much easier to cut a deal.

I’m still not sure I understand what’s going on here, but it seems like there might be two problems:

City attorneys believe that the scare of getting arrested, plus or minus a warning or small penalty, is enough to deter many people8. They have research which seems to back this up. Based on the research, they don’t impose stricter penalties for first-time offenders. But cops don’t believe this research, and feel frustrated that their work is coming to nothing, so they stop arresting people at all.

There’s not enough justice system resources (public defenders, courtrooms, etc) to give shoplifters trials, so the prosecutors have no bargaining power, so they accept plea bargains for minimal punishment.

This makes sense, but I still don’t understand why New York can’t imprison its 327 chronic shoplifters. Even if most normal people get scared straight by an arrest and a warning, these 327 people are obviously not in that category. And even if the city has limited justice resources, surely these are exactly the people who you want to spend those limited resources on.

We found earlier that the deterrence effects of long sentences, relative to short sentences, were weak. But the deterrent effect of crime being illegal at all, as opposed to basically legal and not even resulting in arrest, is very very strong. Here’s Nagin, our token unbiased tie-breaker researcher:

The evidence in support of the deterrent effect of the certainty of punishment is far more consistent than that for the severity of punishment. However, the evidence in support of certainty’s effect pertains almost exclusively to apprehension probability. Consequently, the more precise statement is that certainty of apprehension, not the severity of the ensuing legal consequence, is the more effective deterrent.

So I still think the push for longer prison sentences is a distraction. Instead we should be spending that money on getting more courts and public defenders so we can use the prisons we already have.

Nagin goes on to add:

There is substantial evidence that increasing the visibility of the police by hiring more officers and allocating existing officers in ways that materially heighten the perceived risk of apprehension can deter crimes.

Summary

Long prison sentences can theoretically decrease crime through deterrence, incapacitation, or rehabilitory aftereffects.

Deterrence effects are so weak that we might as well round them off to zero.

Incapacitation effects are strong. The exact strength depends on how many people are already in prison, but a reasonable estimate at the current margin is that each prisoner-year prevents one violent crime and six property crimes.

The magnitude of aftereffects are unclear, and probably range from slightly beneficial to detrimental depending on the population and length of prison term being studied.

One contrarian researcher (Roodman) argues that aftereffects are so large that they approximately cancel out the benefits of incapacitation, and he has some reanalyzed studies that support his position. This is the only credible argument for why prisons wouldn’t decrease crime at all, but AFAIK only this one person believes it.

Everyone else, when they say that prison “doesn’t decrease crime”, is either forgetting about incapacitation, or exaggerating their position that it’s a bad and not-so-effective way of decreasing crime.

A more sober estimate is that a 10% increase in incarceration rates decreases crime rates by 3%.