What Happened To SF Homelessness?

...

Last year, I wrote that it would be very hard to decrease the number of mentally ill homeless people in San Francisco. Commenters argued that no, it would be easy, just build more jails and mental hospitals.

A year later, San Francisco feels safer. Visible homelessness is way down. But there wasn’t enough time to build many more jails or mental hospitals. So what happened? Were we all wrong?

Probably not. I only did a cursory investigation, and this is all low-confidence, but it looks like:

There was a big decrease in tent encampments, because a series of court cases made it easier for cities to clear them. Most of the former campers are still homeless. They just don’t have tents.

There might have been a small decrease in overall homelessness, probably because of falling rents.

Mayor Lurie claims to have a Plan To End Homelessness, but it’s probably not responsible for the difference.

Every city accuses every other city of shipping homeless people across their borders, but this probably doesn’t explain most of what’s going on in San Francisco in particular.

A Big Decrease In Tent Encampments

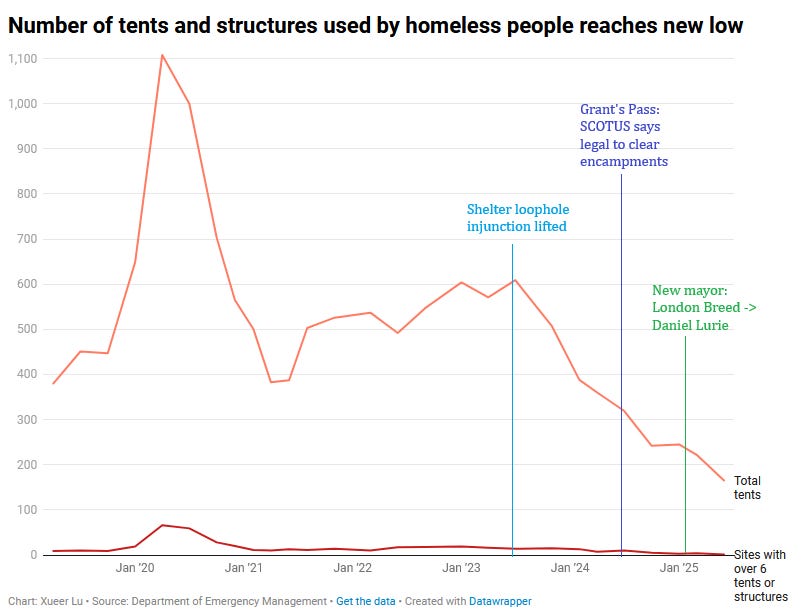

This is the most noticeable effect. Original graph from here, colored text is mine:

After a big spike during the worst part of COVID, tents plateaued until mid-2023, then steadily declined. This timeline doesn’t match the two factors most people credit with the decline - the Grant’s Pass v. Johnson case where the Supreme Court made it easier to clear encampments, and Daniel Lurie taking over as mayor.

What does it match? It might match a legal ruling the city got in September 2023. At the time, it was federally illegal to clear away homeless encampments without offering the homeless people an alternative, eg a shelter bed. San Francisco is chronically short on shelter beds, but cleverly kept a small number of beds in reserve on the exact day of cleanup operations to offer the affected individuals (many of whom would decline anyway). In 2022, a homeless advocacy group sued, saying this was a loophole that made a mockery of the requirement, and the city needed to generally have shelter beds available before it could clear encampments; the judge issued an injunction preventing the city from clearing encampments while the case was going on. In September 2023, another judge disagreed, and restored the city’s right to use this strategy. Then, in the 2024 Grant’s Pass decision, the Supreme Court struck down the entire federal law at issue, making it legal to remove encampments whether or not there were available shelter beds. Encampment numbers fell further.

CalMatters presents the cynical view of post-Grant anti-homeless enforcement. The usual problem with enforcing laws against the homeless is that no plausible punishment can make their lives worse: you can’t fine people without money, or suspend the drivers licenses of people without cars. All you can do is imprison them - but there are too many, it’s too expensive, and the legal justifications are too weak to keep them in for long. The post-Grant environment provides two new levers of control. First, if the homeless have a tent, police can take their tent. Second, if the homeless have other possessions (shopping carts, big bags of stuff, etc), the police can jail them for a day or two, and by the time they get back, someone will have stolen them. Both levers incentivize the homeless to lie low and avoid trafficked areas, to avoid contact with the police. And both remove bulky signs of homelessness that might otherwise block paths, present an eyesore to passers-by, or otherwise kill the vibes of a neighborhood.

Did these measures convince the homeless to shape up and accept social services? Or did they simply make their lives worse by taking their last vestigial shelter, removing their ability to keep possessions for more than a few weeks, and driving them to a miserable nomadic existence? The qualitative interviews in the CalMatters article suggest mostly the latter, although they do include one success story. Another argument for the latter is that there isn’t some vast surfeit of empty shelter beds and subsidized housing for these people to go to. And as we’ll see in the next section, overall homelessness does not seem to have declined as much as the decline in tents. So I think it mostly made the lives of the homeless worse, although there may have been positive effects for a small subset. This isn’t a fatal criticism; the aesthetic and safety improvements are real. But I think it speaks against the argument, common during the height of the crisis, that there was no tradeoff and actually enforcement was the truly compassionate option.

Separately, A Small Decrease In Actual Homelessness

There is weak evidence that overall homelessness has declined in California over the past year.

It’s hard to measure homelessness, because homeless people are hard to find and survey. The gold standard measure is a “point in time count”, where the state chooses one particular day, gathers lots of volunteers, and sees how many homeless people they can find that day. Some counties do this once a year. Others, including San Francisco, do it once every two years. The results of this year’s count (which didn’t include San Francisco) are:

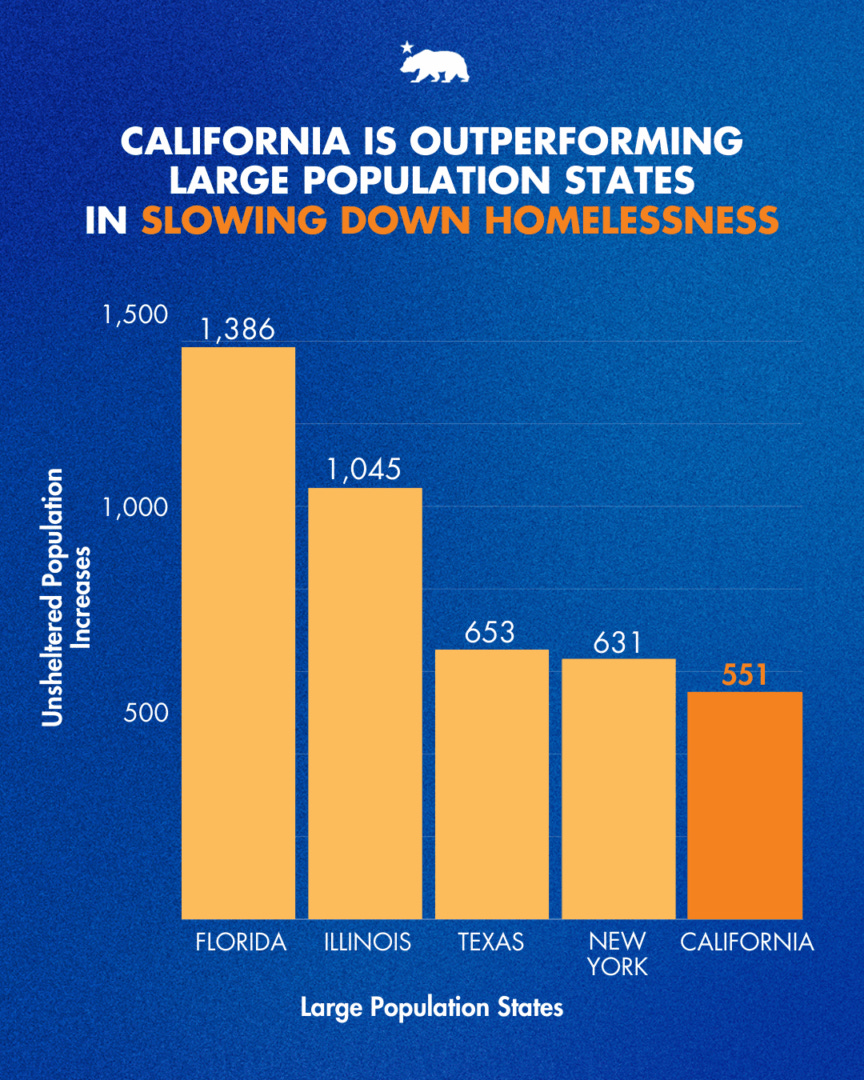

So overall, unsheltered homeless in the areas covered by this year’s count decreased 9%. This looks small, but represents a more impressive victory when compared to previous years (when the homeless population usually went up) and to the US as a whole (where homelessness generally increased during this time).

Why?

Most sources credit improved funding or better local programs. But there was no major change in California homelessness funding during this time. HHAP and Project Homekey, Gavin Newsom’s two flagship homelessness initiatives, have been around for years without major changes in scale. A 2024 ballot measure (Proposition 1) raised billions of dollars for homelessness relief, but this is being spent on facilities that are still under construction. On the opposite side, there is widespread concern about next year, when Trump budget cuts will decrease operations funding. But for now, the budget remains at a plateau, neither significantly up nor down, unable to explain the turnaround.

Might the clearing of tent encampments have encouraged the homeless to use shelters? Maybe, but sheltered homelessness only increased by a quarter of the amount that unsheltered homelessness declined, and most of that probably came from the construction of new shelters - it’s not like there were loads of unused beds for the tent denizens to take. So this can’t be very much of the effect.

I think there are most likely two main causes.

First, the clearing of tent encampments, and other enforcement, encouraged homeless people to hide. Hidden homeless people are harder to count than homeless people living in conspicuous tents. Therefore, the count is lower.

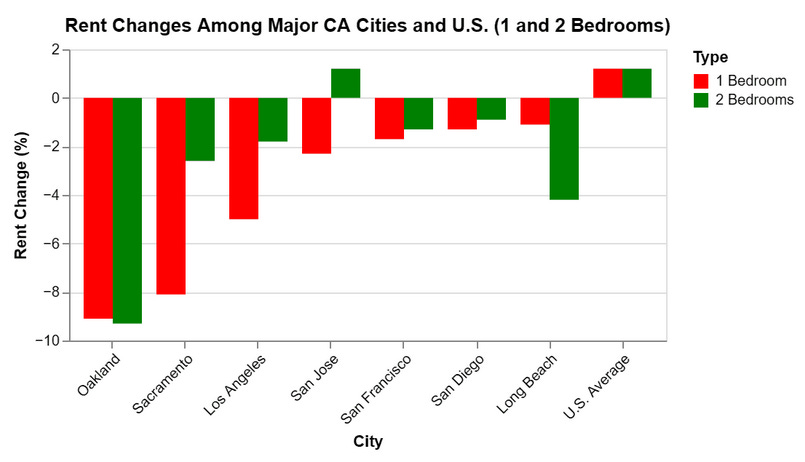

Second, rents fell in most big California cities. Although unsheltered homeless usually can’t afford apartments at any rent, low rents still make it easier for friends and family members to house them.

What brilliant policy victories caused this affordability win?

Interestingly, the report suggests that the primary driver behind the falling rental prices in California is not an increase in housing supply, but rather a decrease in demand. In recent years, the Bay Area and Los Angeles have witnessed substantial population outflows and job losses, which have not yet been fully recovered. Moreover, California recorded the highest unemployment rate among all states in April 2024.

Ah well, nevertheless.

We don’t have this year’s numbers from San Francisco. But assuming it followed the state trend of -9%, this is probably too low for anyone to notice. If you’ve personally felt like there are fewer homeless people around, it’s probably because of the encampment cleanups and the subsequent tendency for them to lie low.

Mayor Lurie’s Policies Probably Aren’t Primarily Responsible

The strongest evidence for this is the same graph as before:

The second strongest evidence is that approximately the same pattern has happened in every affected California city during this period, supporting the hypothesis that this is downstream of Grant’s Pass and other larger trends.

But also, Lurie’s homelessness policy just isn’t that impressive. He ran on a platform of creating 1,500 extra shelter beds, which would have put a significant dent in the problem. But after creating 100 - 200, he admitted this was too hard and gave up. Otherwise, it sounds the same as every mayor’s Plan To End Homelessness - reorganize local services, fund street response teams, coordinate and streamline blah blah blah. Even the name - Breaking The Cycle - gives me deja vu. Didn’t Gavin Newsom call his homelessness plan that? No? Mayor Breed? Jerry Brown? Daenerys Targaryen?

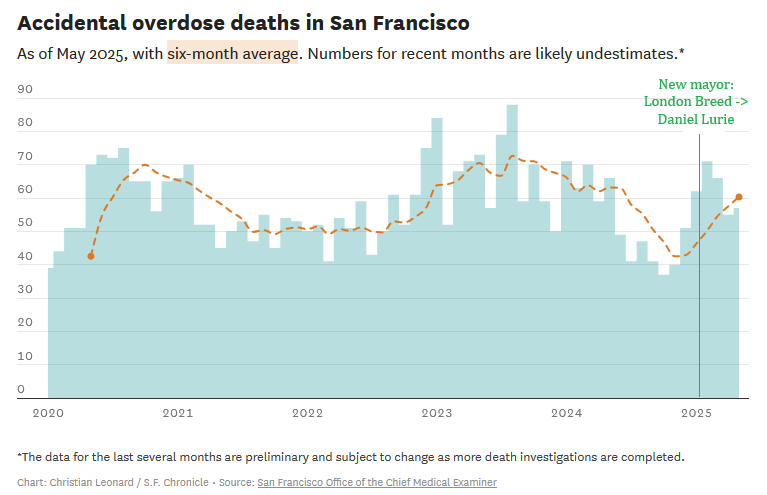

Mayor Lurie’s other big homelessness-related policy was getting tough on fentanyl - clearing up the open-air markets, cutting “harm reduction” programs that give free drug paraphernalia to users. To his credit, there are many fewer open-air drug markets now. As for drug-related deaths:

…preliminary results look discouraging.

Why? Some experts argue that the clearing of open-air markets shifts the dealer-addict relationship from an iterated game to a one-shot: since law enforcement prevents anyone from staying in the same place too long, addicts move from dealer to dealer, encouraging dealers to try exploitative strategies rather than cultivating repeat customers. Those exploitative strategies include toxic or spiked merchandise, hence the increased overdoses. Others argue that the harm reduction programs successfully reduced harm, and stopping them had the predictable effect.

But it looks to me like things get worse slightly before Mayor Lurie took office, and that in any case the new regime is a return to form after an anomalous trough. This article argues that none of this has anything to do with local policy; some foreign countries successfully cracked down on fentanyl in 2024, raising prices and creating a shortage. Then in 2025 the traffickers recovered, and supply came back.

Everyone Accuses Everyone Else Of Shipping Them Homeless People

Look too closely into discussions of why homelessness is up or down in some particular city, and you’ll find dark murmurs about how they’re shipping problem individuals away, or getting duped by other cities doing the same to them.

The Berkelians say SF has sent its homeless to Berkeley. The Oaklanders say no, to Oakland. The Sacramentans say Sacramento. And don’t forget the ones sent to other states! Meanwhile, former SF mayor Gavin Newsom has claimed that the majority of its own homeless people come from Texas (this is obviously false).

Some of these claims make sense. San Francisco has three programs that bus its homeless people out of the city. Previously, they would only do this if social workers could prove the person had a family member willing to support them in the new city. More recently, they lowered this standard to “some connection” to the destination.

But I don’t think this caused a large drop in SF homelessness, for three reasons.

First, we have no evidence that any such drop in homeless numbers occurred - just a decrease in tent encampments and visible dysfunction.

Second, the new lower-standards busing program only got about 100 people a year - pretty small compared to the scale of the problem.

Third, the data above show general homelessness declines across California. If SF were exporting its homeless, you would expect other counties’ numbers to increase. Instead, it seems more likely that SF’s numbers are going down (if they are going down) for the same reason as everyone else’s.

We’ll have more information next year, when Alameda County releases homelessness numbers. Alameda, which contains Oakland and Berkeley, is a natural export destination for San Francisco.

So What Happened To Homelessness?

This is a maximally boring story.

There’s a natural tradeoff where governments can enforce laws against the homeless in ways that make them less visible and annoying, at the cost of making their lives harder, eg it can take away their tents.

In the past, they didn’t do this, out of a combination of tender-heartedness and legal restrictions. After the homeless became extremely visible and annoying, voters felt less tender-hearted, and the courts lifted the legal restrictions. So cities took the tradeoff. This is the big effect that everyone noticed.

At the same time, there were some small effects from increased funding, falling rents, drug market clearing, and busing programs. Realistically nobody would have noticed any of these; the big effect is from encampment clearing.

Have we learned anything? I don’t think we learned the sort of thing we hoped we might learn, the lever we could push to solve everything with no downsides. But:

I had previously thought there weren’t really any levers that could improve the problem at all, short of mass incarceration. I hadn’t considered that taking people’s tents and possessions would have such a strong aesthetic effect that most people would consider the problem solved from an annoyance/visibility perspective. I think my failure was some combination of 1: not realizing how much people hated tent encampments in particular, as opposed to (for example) weird people wandering the street in rags talking to themselves 2: not realizing how many options the homeless have for “lying low” when they really don’t want to be found (and therefore how elastic visible homelessness is with respect to legal crackdowns).

I don’t think the “getting tough is the real compassion” people come out looking prescient either, because the kind of getting tough that cities went with wasn’t compassionate at all, and seems to have made the lives of the homeless worse - although so far this claim relies primarily on anecdotes and very preliminary overdose death numbers.

In the end, both sides underestimated how basic the tradeoff was, and the system gave the voters what they wanted regardless.