Vibecession: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

...

The term “vibecession” most strictly refers to a period 2023 - 2024 when economic indicators were up, but consumer sentiment (“vibes”) was down. But on a broader level, the whole past decade has been a vibecession.

Young people complain they’ve been permanently locked out of opportunity. They will never become homeowners, never be able to support a family, only keep treading water at precarious gig jobs forever. They got a 5.9 GPA and couldn’t get into college; they applied to 2,051 companies in the past week without so much as a politely-phrased rejection. Sometime in the 1990s, the Boomers ripped up the social contract where hard work leads to a pleasant middle-class life, replacing it with a hellworld where you will own nothing and numb the pain with algorithmic slop. The only live political question is whether to blame immigrants, blame billionaires, or just trade crypto in the hopes that some memecoin buys you a ticket out of the permanent underclass.

Meanwhile, economists say things have never been better.

Are the youth succumbing to a “negativity bias” where they see the past through “rose-colored glasses”? Are the economists looking at some ivory tower High Modernist metric that fails to capture real life? Or is there something more complicated going on?

We’ll start by formally assessing the vibes. Then we’ll move on to the economists’ arguments that things are fine. Finally, we’ll try to resolve the conflict: how bad are things, really?

Are We Sure The Vibes Are Bad?

I’ll assume you’ve already heard the complaints about the economy coming from the media, social media, et cetera. But are we sure there isn’t a meta-vibecession? The vibes about the vibes are bad, but really, the vibes are good? Maybe the media just -

- oh god, no, it’s even worse than I thought. The vibes are awful.

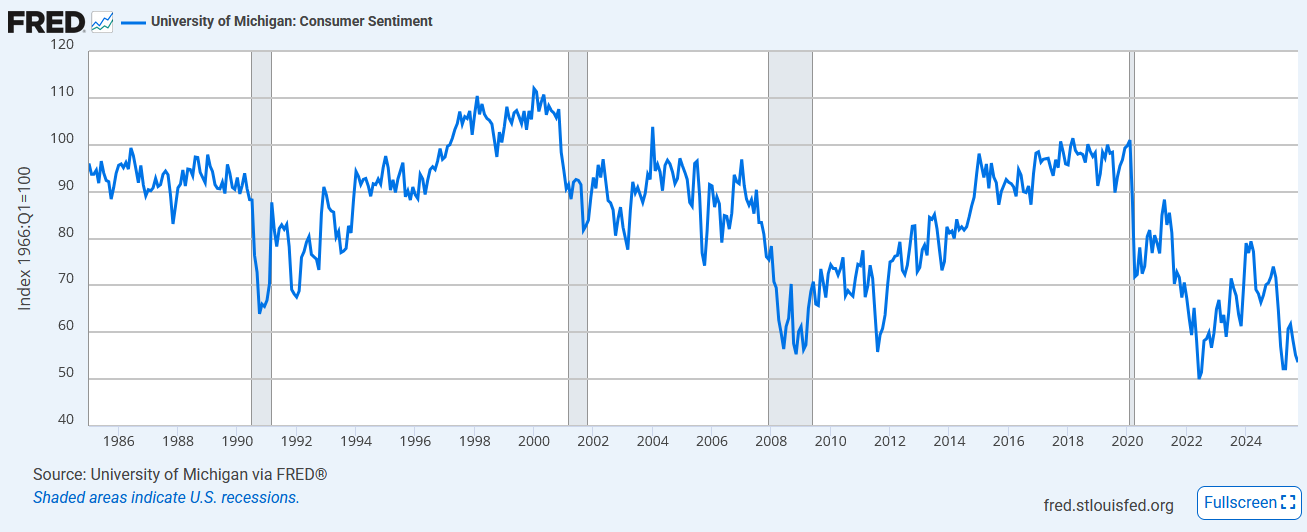

This is the official measure of vibes, the Index of Consumer Sentiments. Can we trust it?

One reason not to trust it is that most of its questions take a form like “do you think things are better than last year?” or “do you think things will be better next year?” These are local and don’t really allow you to compare today vs. 1980. But consumers are terrible at answering these questions in the spirit in which they’re intended; for example, when the economy is bad, “do you think things will be better next year?” reaches a low, even though bad economies are exactly when you would expect next year to be better (through mean reversion). So it’s probably fair to treat this as overall “vibes: good or bad?”

Another reason not to trust it is that they changed the survey methodology in 2024, causing multiple trend breaks; instead of adjusting for this, they “smoothed it out” so people wouldn’t notice! This seems irresponsible and I don’t know how they got away with it. Everything after 2024 should arguably be ~5 points higher. But even adding 5 points, things now look pretty grim.

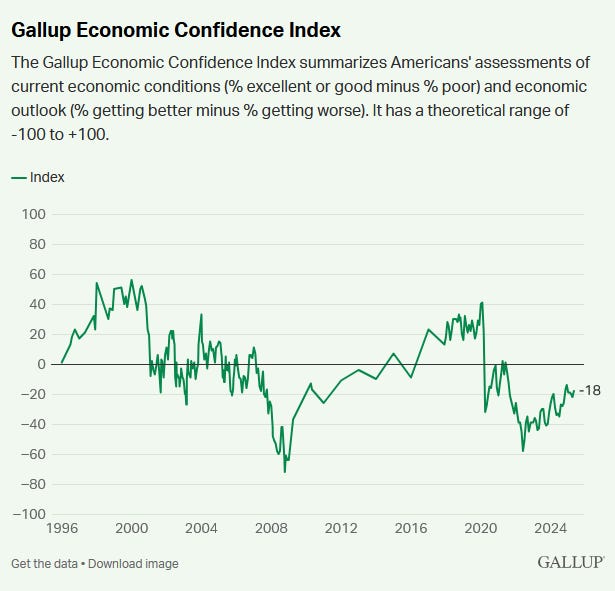

The Gallup Economic Confidence Index, which doesn’t have the methodology problem, looks pretty similar:

This is a combination of an absolute question (“how are conditions?”) and a relative question (“are they getting worse or better”), but you can disambiguate them here and get similar results.

I conclude the vibes are actually bad.

There is one anomaly, which is that I remember people complaining about the bad economy and the Boomers and hellworld since well before 2020 (consider the Trump and Sanders campaigns), but the official vibes didn’t crash until COVID. Is my memory faulty?

The Economists’ Seemingly Rosy Statistics

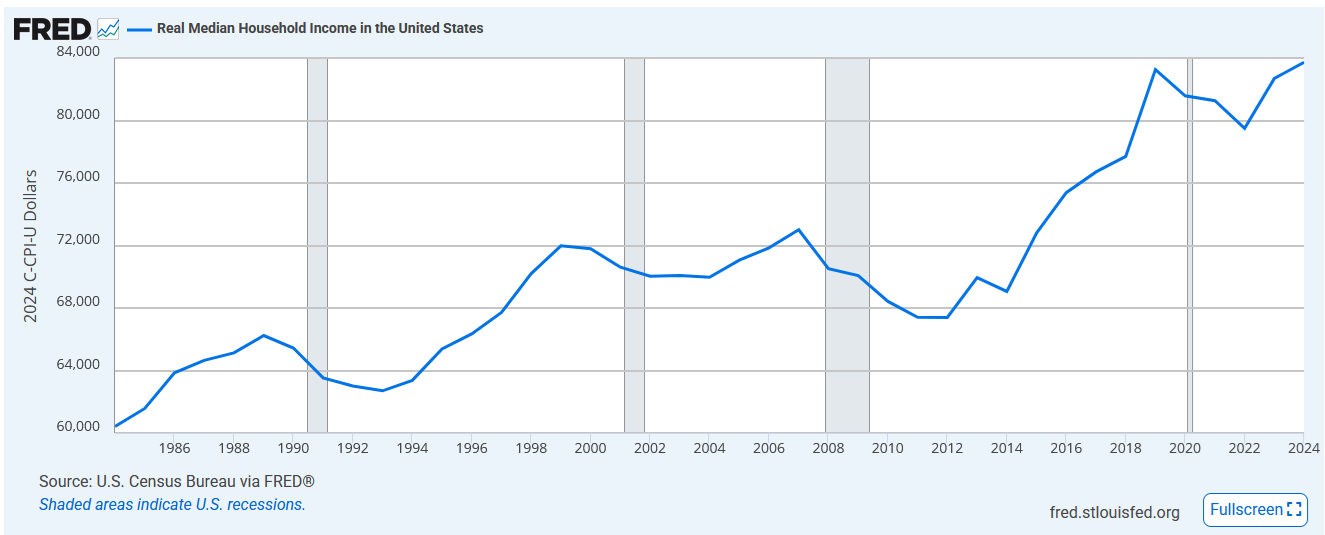

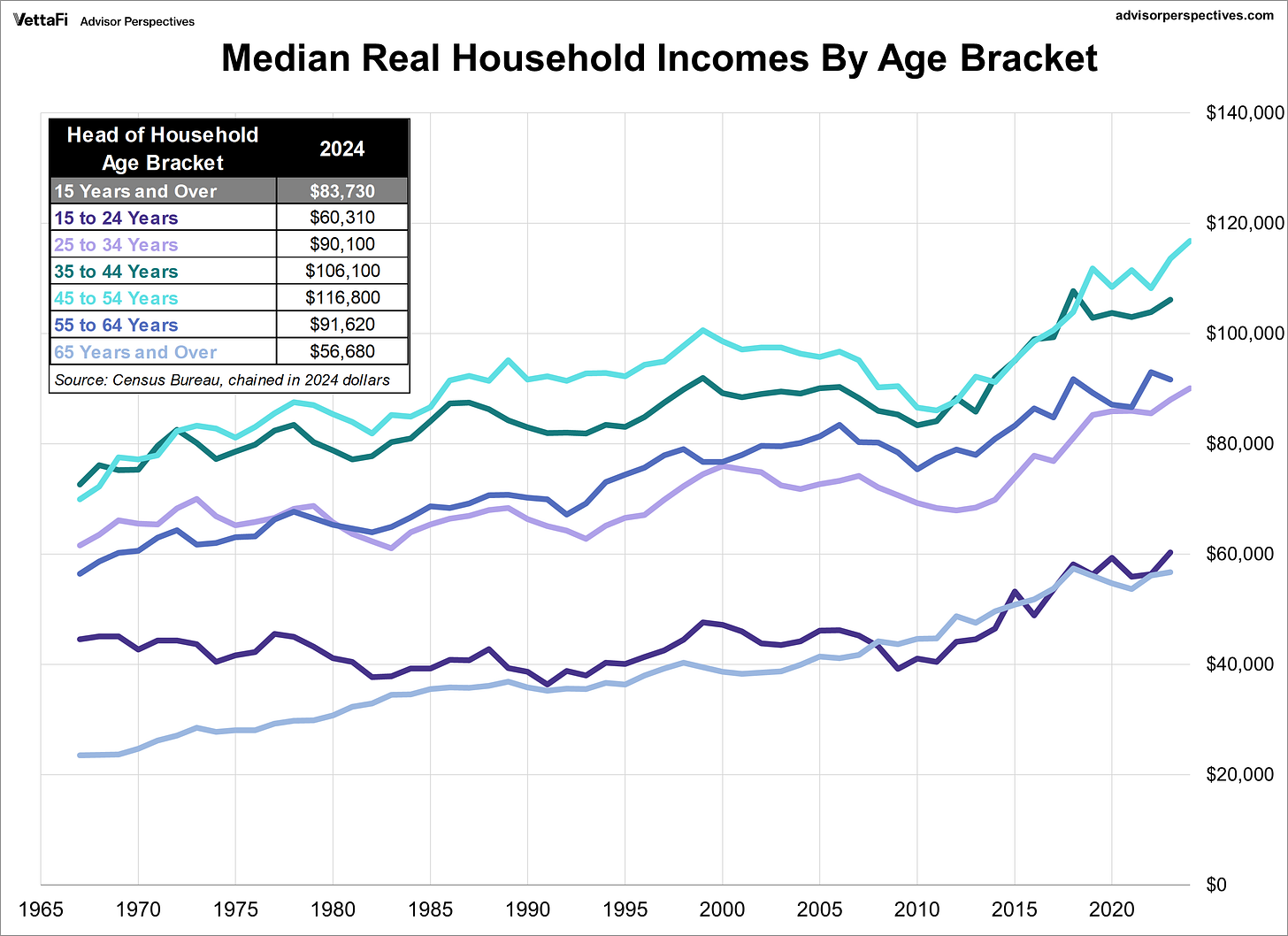

Here’s real median household income in the US over time (source):

People today earn 33% more than they did during the Boomers’ heyday.

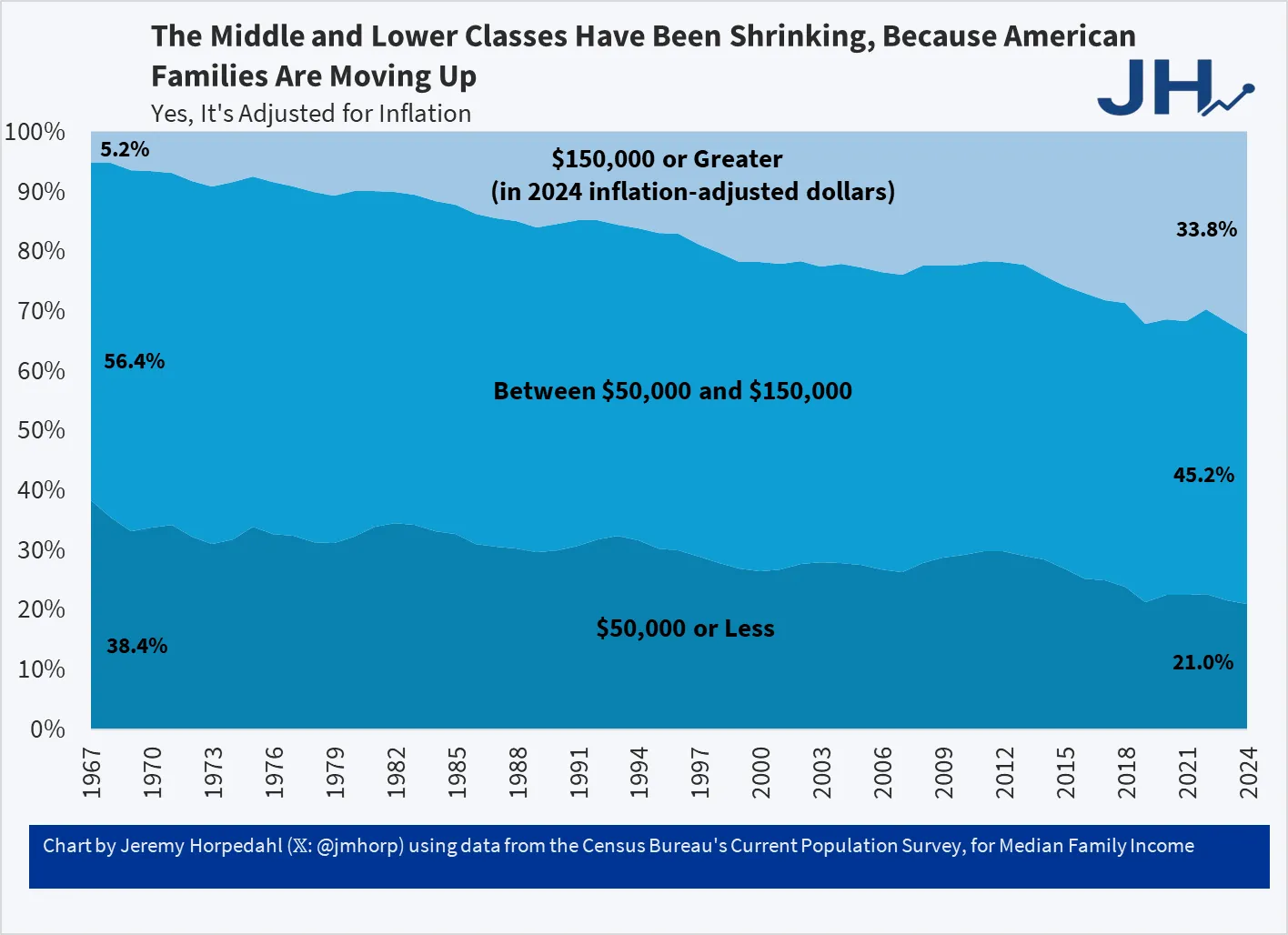

Might this just be a few billionaires bringing the average up, while the incomes of ordinary people stagnate? No: this is median income. You’re thinking of mean income. The mean can be brought up by a few outliers; the median represents the exact most ordinary member of society. If you insist, here are the same data presented as the share of society making more than a certain threshold in inflation-adjusted dollars (source):

Might cost-of-living increases have eaten all of these gains and then some? No: this is real median income, ie adjusted for inflation. Cost-of-living increases are a type of inflation, so those should be priced in.

Might this just represent old people doing better, while the young are left behind? No: here are the same data disaggregated by age group (source):

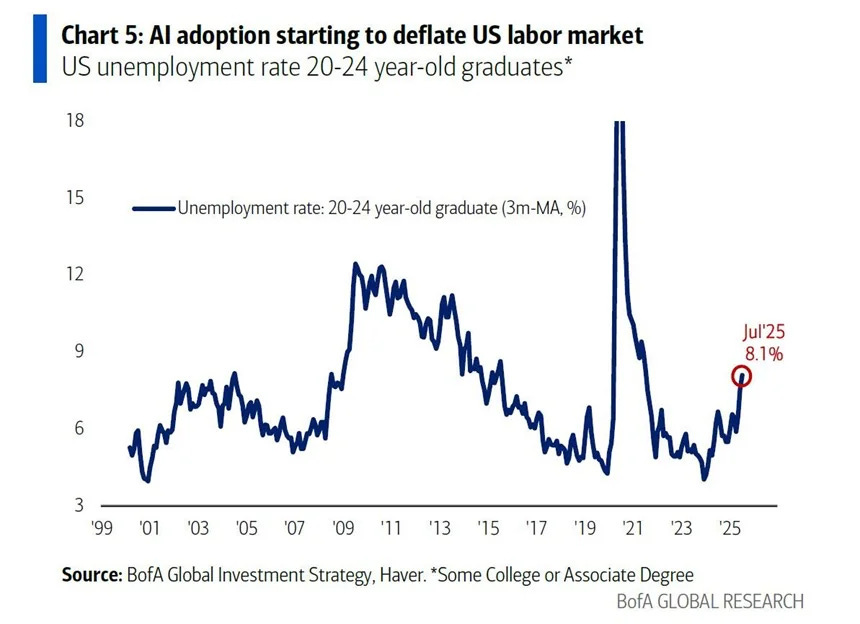

Young people’s incomes have increased as fast as everyone else’s. And the youth-specific unemployment rate was near historic lows until last year (some people blame the current uptick on AI, but this is too recent to have caused the vibecession):

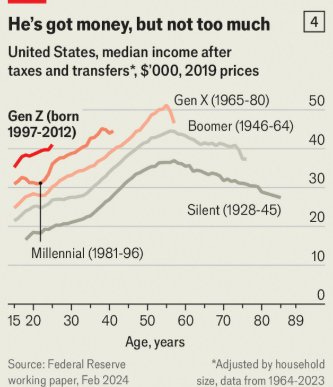

Here’s an attempt to compare generations directly. We can’t do this as a point-in-time estimate, because late-career old people will always earn more than early-career young people, but we can compare how much people made in inflation-adjusted dollars at the same ages:

Just as our previous graphs imply, Millennials and Zoomers earn significantly more than Boomers did at the same age, even in inflation-adjusted dollars.

So, the economists conclude, maybe it really is just vibes. We know of other cases where the public believes things are worsening even as they get better: crime rates are the classic example.

But most people judge crime rates by what they hear on TV. Vanishing economic opportunity is much more personal. Can people really be wrong about something so close to their own lives?

Fine, You’ve Proven The Contradiction We Already Knew About, Get To The Point Where You Solve It.

We start by looking at other people’s proposed solutions.

(Briefly) Declining Real Wages

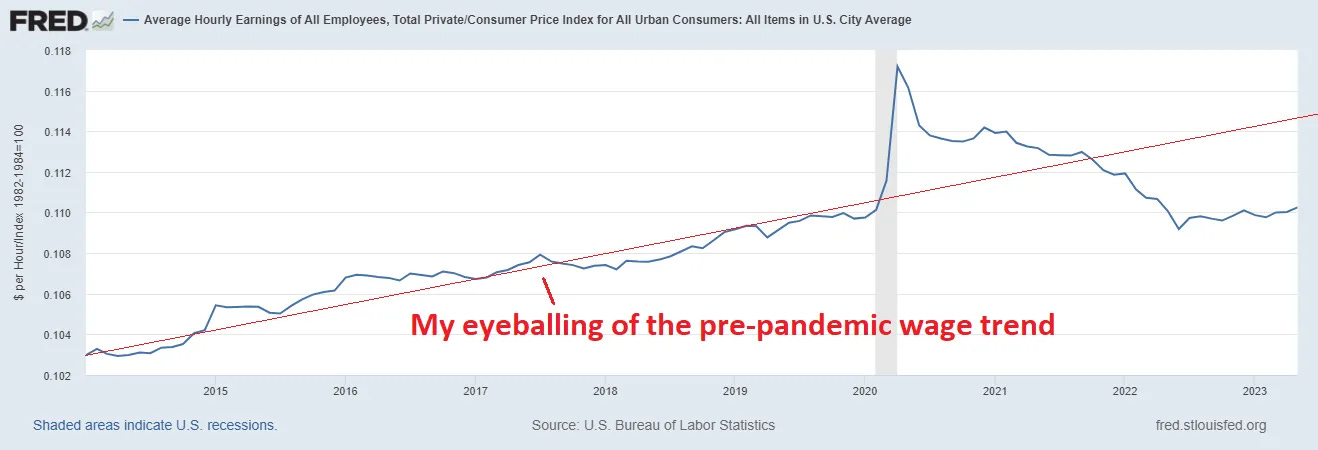

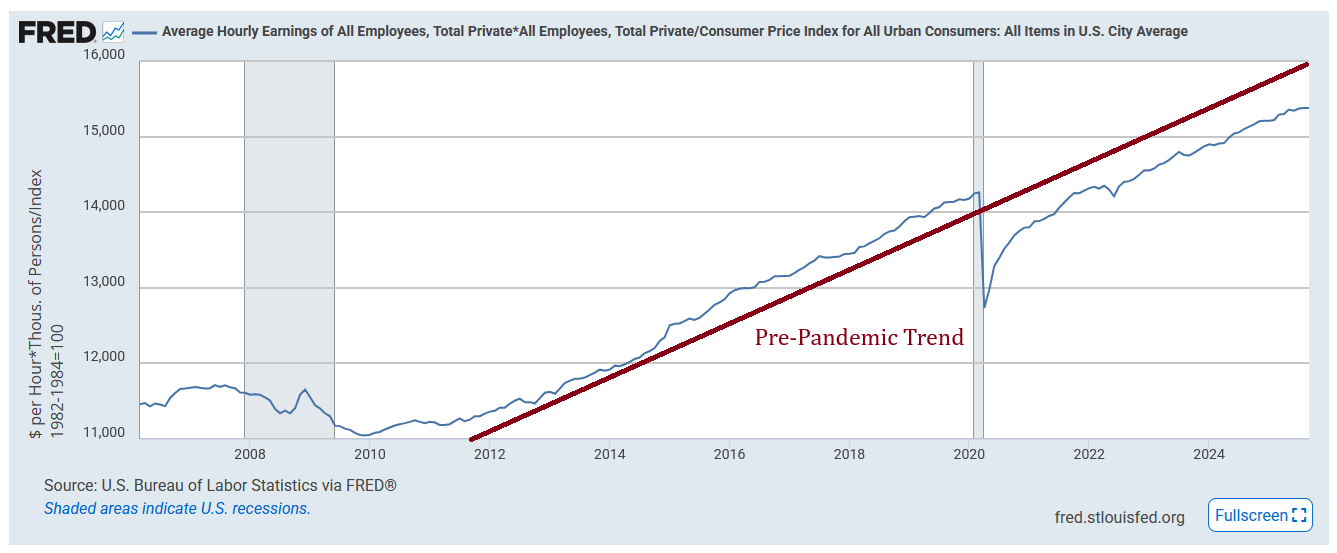

The term “vibecession” most strictly refers to the period 2023 - 2024 when economic indicators were up, but consumer sentiment was down. During that period, Noah Smith popularized a paper by Darren Grant arguing that this corresponded to a brief decline in real wages, even though stocks and other indicators kept rising:

During COVID, the government instituted various relief programs which temporarily gave people lots of money (the spike). This caused some inflation, which temporarily lowered real (ie inflation-adjusted) wages. Then inflation calmed down and real wages started rising again - thus Noah’s post title, “The End Of The Vibecession?”

With the benefit of two more years of data, we see that Noah and Darren were right about the trend:

Wages never jumped back to the point where they would be if the pandemic had never happened, but they’re back to growing as fast as ever.

So this could explain the mini-vibecession of 2023-2024. Still, I claim there is a broader vibecession. Young people felt closed out from opportunities before 2023, and they still feel that way.

Since only the 2023-2024 period saw falling real wages, this can’t be the full explanation.

The Housing Theory Of Everything

John Burn-Murdoch, after examining some of these same data, agrees that wages can’t be the full story. He writes:

Are millennials wrong to complain? I fear not. The per capita measure is a beautifully simple rejoinder, but it misses one crucial detail. Wealth accumulation — just like income — matters primarily to millennials today as a means to home ownership, especially as we move into an era of high interest rates. If we deflate wealth by the index of house prices instead of the CPI, millennials’ assets only go about half as far as boomers’ once did. We’re left with a smaller millennial deficit than the original chart implied, but a deficit nonetheless.

The YIMBYs at Works In Progress go further, and present The Housing Theory Of Everything (or at least of everything bad):

Try listing every problem the Western world has at the moment. Along with Covid, you might include slow growth, climate change, poor health, financial instability, economic inequality, and falling fertility. These longer-term trends contribute to a sense of malaise that many of us feel about our societies. They may seem loosely related, but there is one big thing that makes them all worse. That thing is a shortage of housing: too few homes being built where people want to live. And if we fix those shortages, we will help to solve many of the other, seemingly unrelated problems that we face as well.

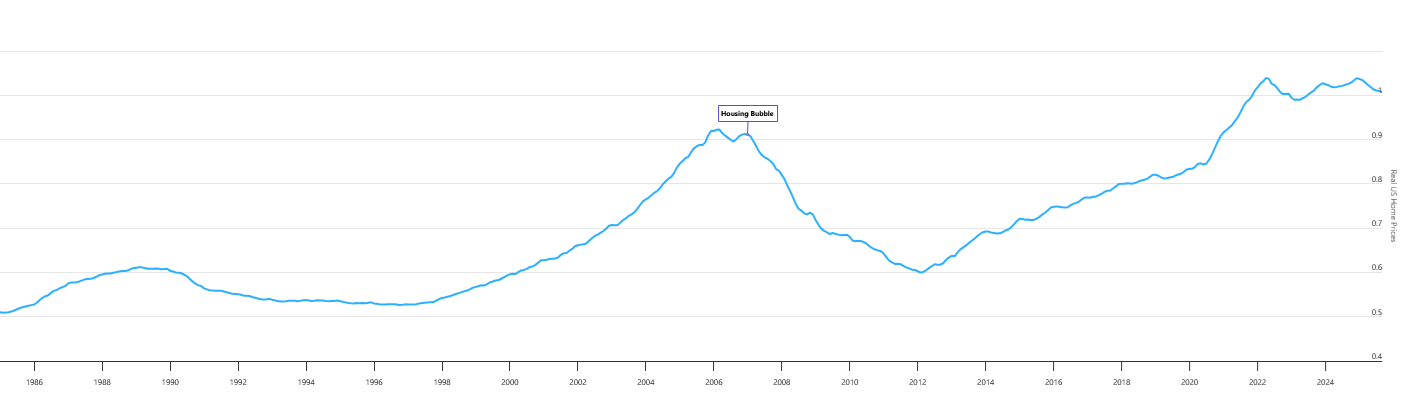

Here is the Case-Shiller index, the standard measure of US home prices. I’ve started it in 1985 to match our other graphs:

During this time, average home price has approximately doubled.

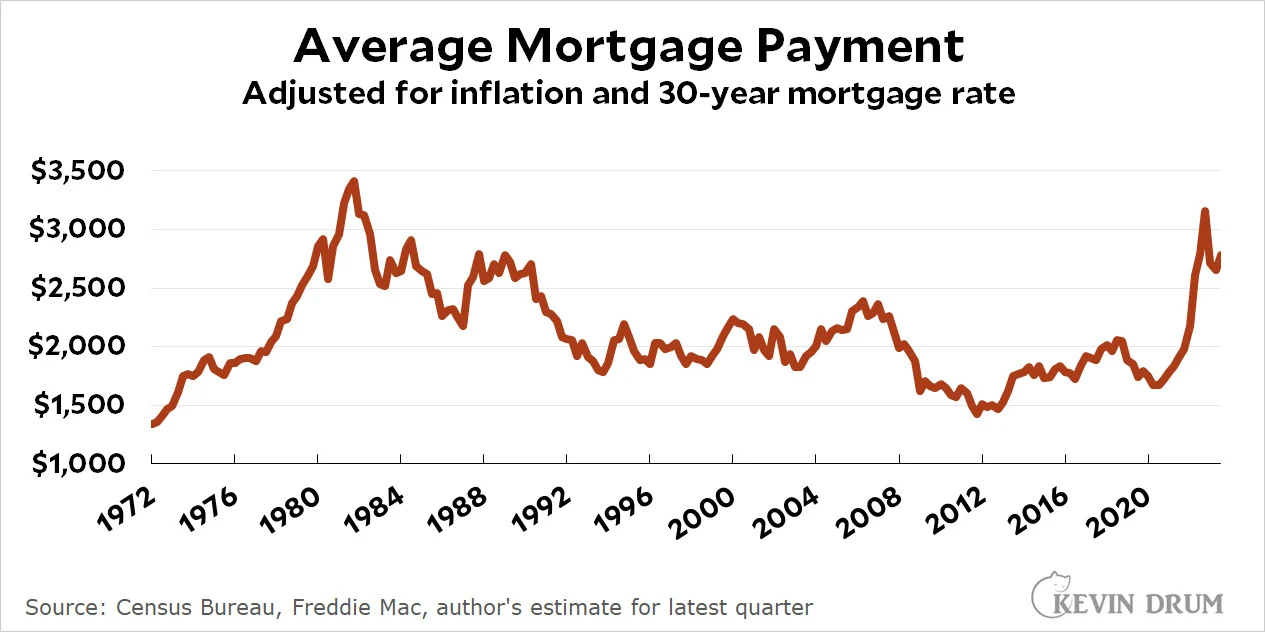

Might this only reflect falling interest rates? That is, suppose people can only afford a certain level of monthly mortgage payment. When interest rates are high, that mortgage payment would correspond to a cheap house; when they are low, that same person willing to spend that same amount could buy a more expensive house. To really work with this, we need average mortgage payment over time.

Kevin Drum has this up to 2020:

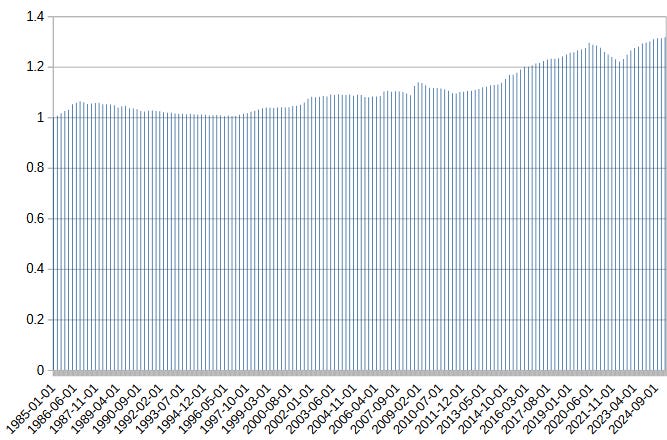

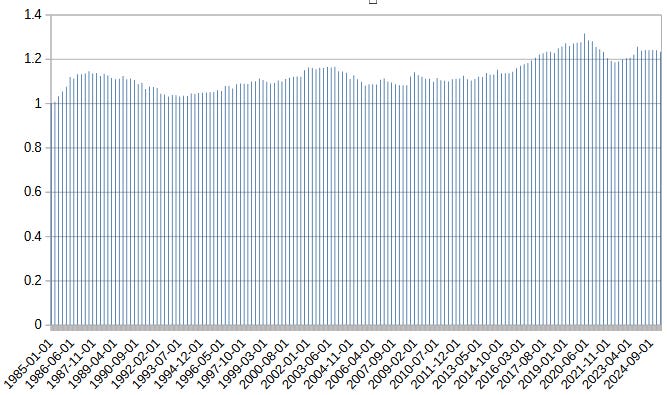

…but it matters a lot whether this that spike at the end is a temporary pandemic effect or a permanent regime change. I’ve tried to calculate an updated version from FRED data:

This matches Drum’s data enough to build confidence, and it shows that the post-pandemic spike has lasted. Mortgage payments are almost twice as high as in the 2010s.

The COVID housing spike was partly a function of lockdown locking people in their houses (meaning that having a nice house was more important), and partly a function of the government cutting mortgage rates to alleviate lockdown-related economic distress. But why did it last even after COVID lockdowns ended?

Partly because the homebuyers who bought houses during COVID will never move again, because that would mean giving up their great mortgages.

Partly because remote work is still popular, meaning that having a nice house remains more important than before the pandemic.

Partly because although lockdowns dealt the original blow to the construction industry, tariffs and immigration crackdowns keep punching it while it’s down.

Partly because of sticky prices - if you bought your home for $1 million, you will feel psychological resistance to selling it for $800K, and are likely to hold out for $1 million even if $800K is the “market price”.

Partly because the bill for ~50 years of NIMBYism has finally come due.

Does this fully solve the vibecession problem? I don’t think so. For one thing, if we take the Trump and Sanders argument seriously, the bad vibes had already started in the late 2010s, when real mortgage prices were the lowest in decades. And even today, mortgages are no worse than in the 1980s, during the high interest rates of the Volcker Shock.

For another thing, the loudest complaints come from young people who don’t have mortgages anyway. What about rents?

Inflation-adjusted rents have gone up 30% since 1985. And the growth accelerated in the mid-2010s, around when vibecession-style complaints began to grow.

But people are earning more now. What about rent as a fraction of salary?

Here the change is smaller: an increase of maybe 10% since the early 2010s. This is bad. But on its own, it’s hardly hellworld and the shredding of the social contract.

Finally, yes, housing has gotten more expensive. But other things have gotten cheaper. That’s why inflation/cost-of-living is only what it is, and not some larger number. We already adjusted for inflation. This is just putting a magnifying glass on one aspect of the thing we already adjusted for.

Summary of this section:

Mortgages have gone up 100% since 2021. But this doesn’t fully explain the vibecession, because it seems to have started before that, and even non-mortgage-holders are angry.

Affordability of rent has gone down 10% since the 2010s, but could a 10% change really cause this much concern?

In theory, these should be counterbalanced by other things getting cheaper.

Miscalculation Of Inflation

Adjusted for inflation, everything is fine. So if we notice that things aren’t really fine, maybe we calculated inflation wrong.

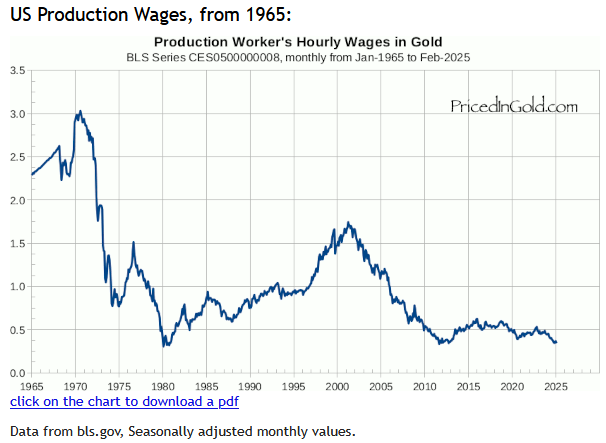

Every so often, someone makes a site with a name like TruthStats.org claiming that all government economic statistics are lies, and inflation is 10,000% higher than reported. Sometimes these use gold as a “real” price, and find that wages as measured in gold have gone down over time (source).

Mainstream economists argue that they price inflation by measuring the price of a basket of the most-frequently-bought goods, like eggs, milk, cars, apartments, etc, weighted to the amount that the average American spends on each. Since real people don’t buy gold, but do buy the most frequently bought goods, this is a better measurement of whether the affordability of normal life is going up or down.

My heuristic is that when the mainstream consensus refuses to engage with a critique and hem and haw about it being “problematic”, they are usually wrong. But when they explicitly declare “This is incorrect” and write papers explaining their reasoning, they are usually right. The experts have explicitly called the various TruthStats.org sites incorrect, and their arguments seem sound. I side with them.

That having been said, there are subtler ways inflation measures can fail. The CPI takes a shortcut by abstracting mortgages to “imputed rent”, ie how much an owner would have to pay themselves to fairly rent their own home. But in cases where rents and mortgages diverge (like today) this underestimates the cost of mortgages. Still, this is only the same problem we found above: sure, mortgages have been high since 2021, but not before that, and not in a way that affects people who aren’t on the property ladder.

I think inflation calculations are pretty good.

Fine, Let’s Talk More About Inequality

We already saw that the discrepancy isn’t trivially inequality: even median wages are rising. But is there some more complicated way that it could be inequality? For example, what if the top 75% of people are doing better, but the bottom 25% are really bad?

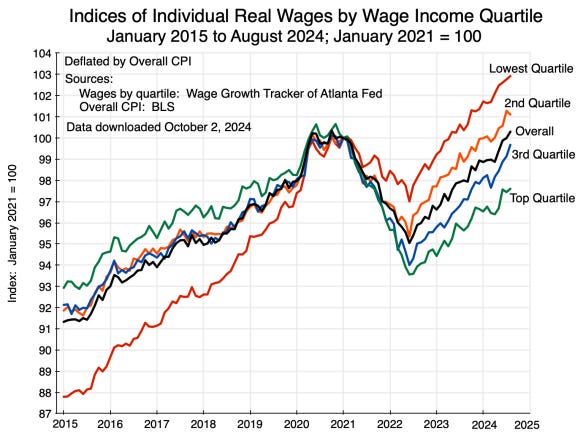

No. As we see here, over the past decade, the bottom quintile has done (relatively) best of all:

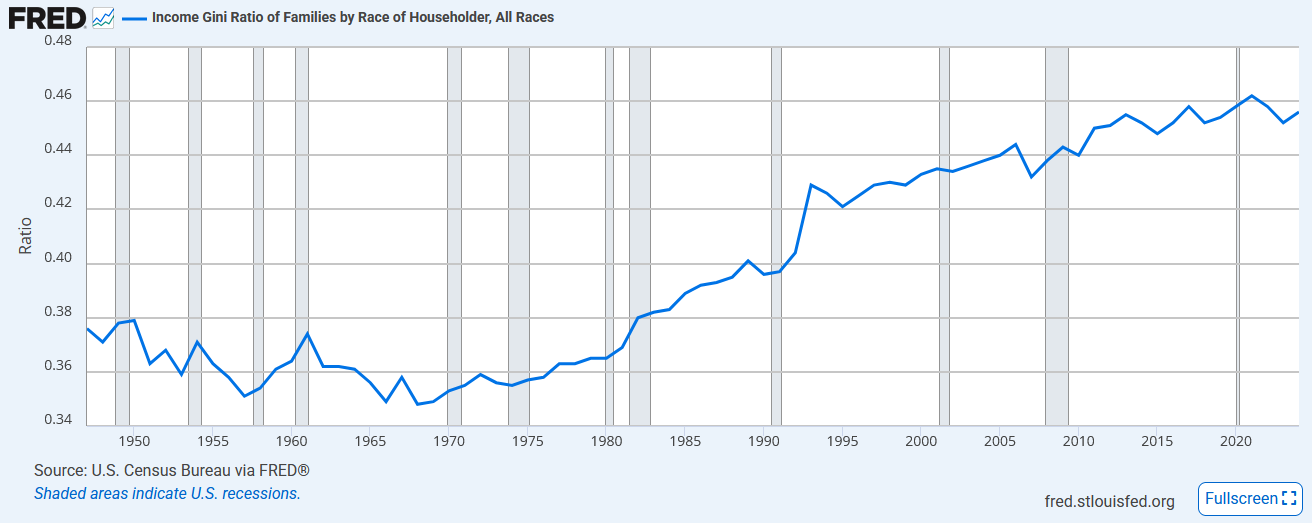

Although US income inequality is high and the secular trend is upward, the past decade or so, when vibecession complaints have been at their worst, has seen a relative plateau:

Relative Generational Inequality

People don’t always notice their absolute wealth. They compare themselves to their neighbors, their parents, or themselves in the past. Might young people be doing better, yet still feel left behind because old people are doing better still?

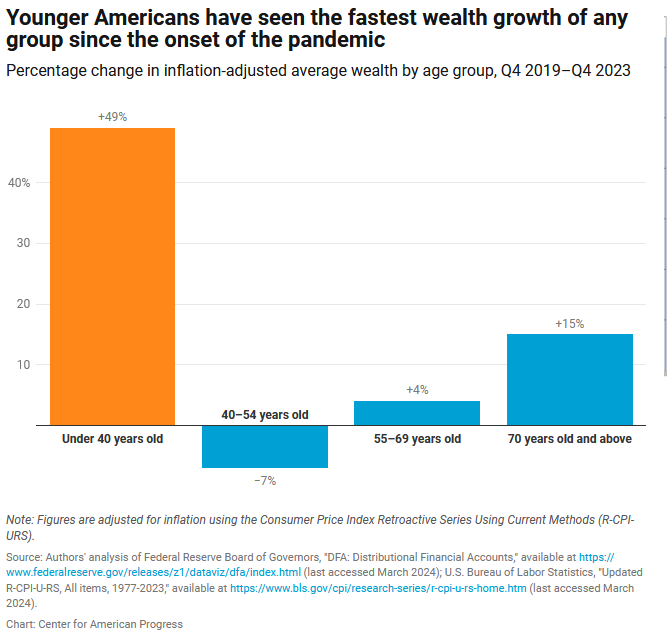

This isn’t happening on an individual level (source):

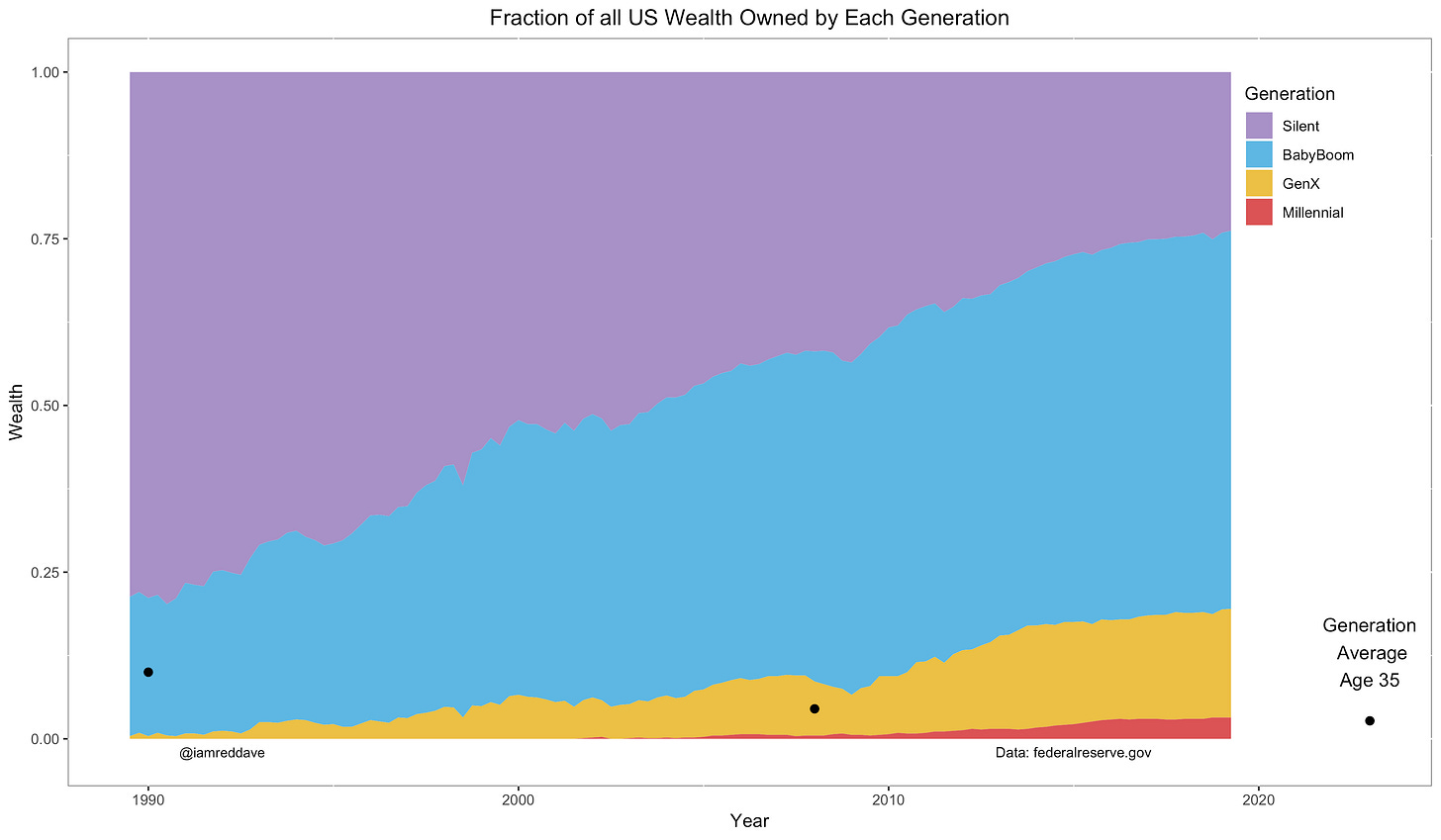

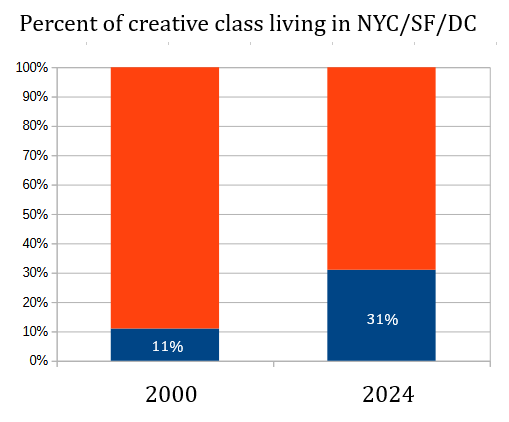

But on a cohort level (how many resources each generation controls as a group), it is happening. Thirty years ago, people under 35 held about 11% of total wealth. Today, they hold about 4%. (source):

How can this be? Declining fertility and increasing lifespans have flipped the population pyramid. Even if the (average young person : average old person) income ratio has stayed the same, the (total number of old people : total number of young people) ratio has increased, so old people as a class hold more of the wealth.

But can people notice this? Sure, you compare yourself to your friends, neighbors, etc. But do you really compare your age cohort to other age cohorts? How do you even mentally calculate the total percent of wealth owned by old people? Aren’t most old people hidden away in retirement communities where young people don’t see them?

Second Derivative

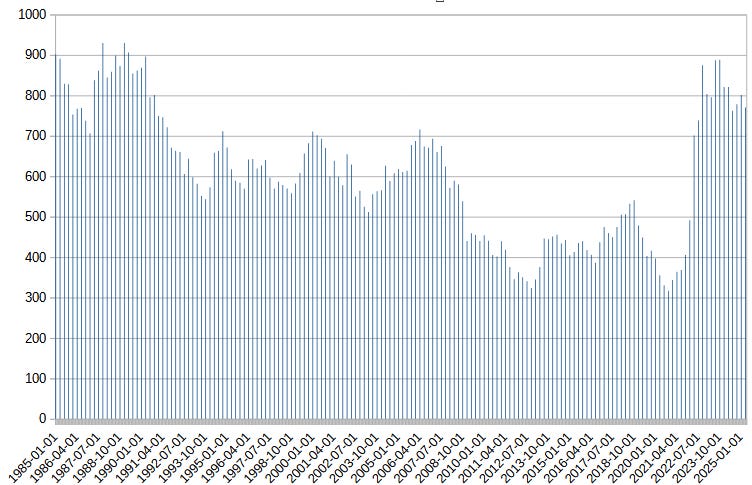

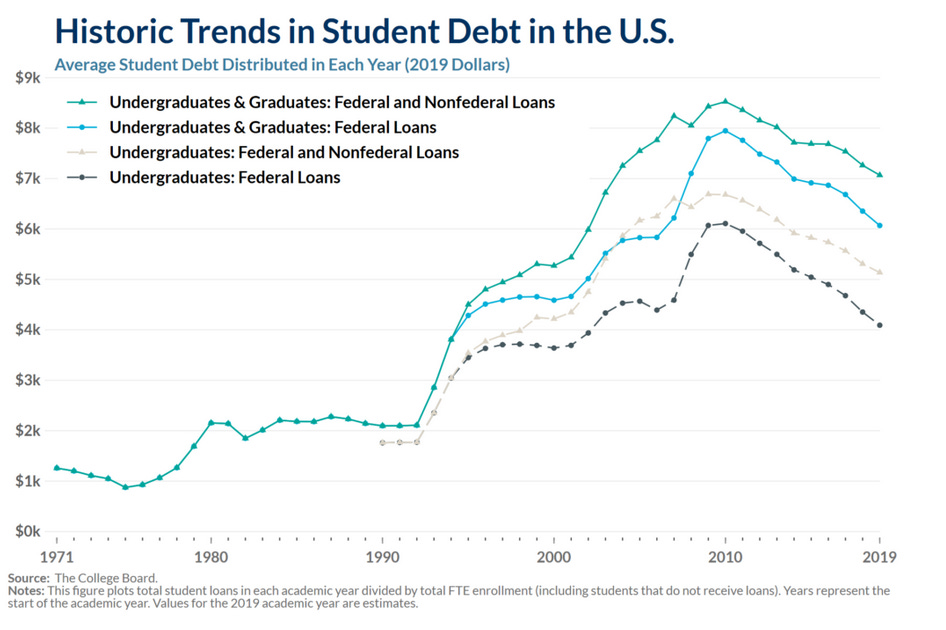

The rate of GDP growth has decreased over the past several decades. Although GDP growth is still positive, if you were expecting the high GDP growth of the past, the current level of low GDP growth might seem lower than expected, which could be confused with negative growth and things getting worse.

But can people really sense the second derivative of GDP over decades-long timescales?

It seems strange for there to be a valid complaint about the economy (decreasing national dynamism) which is so close to the disputed complaint (you personally have less opportunity), while still dismissing the latter as “just vibes”. Still, the connection remains unclear.

Debt

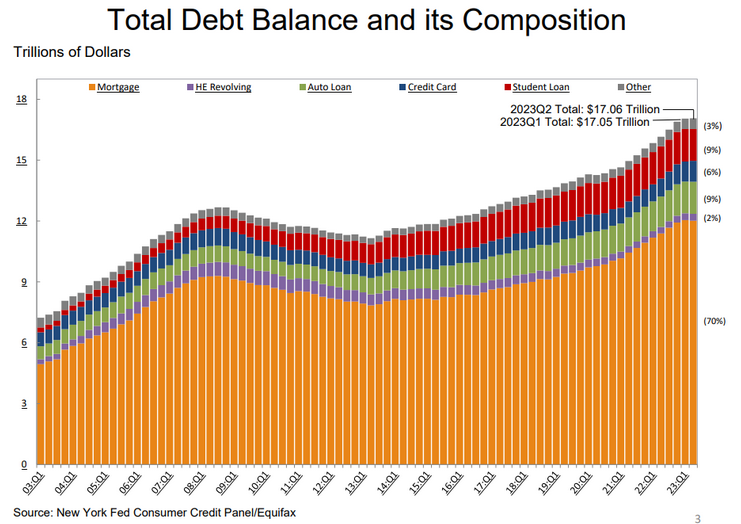

Might young people today be earning the same incomes, and face the same expenses, but saddled by more debt?

Probably not (source):

This is nominal dollars, so even though it looks like total debt went up from $7T to $16T, net of inflation it’s only from about $13T to $16T over that period. And there are more Americans now than in 2001, so debt per person might not have gone up at all. And most of the increase is mortgage, which we’ve covered already.

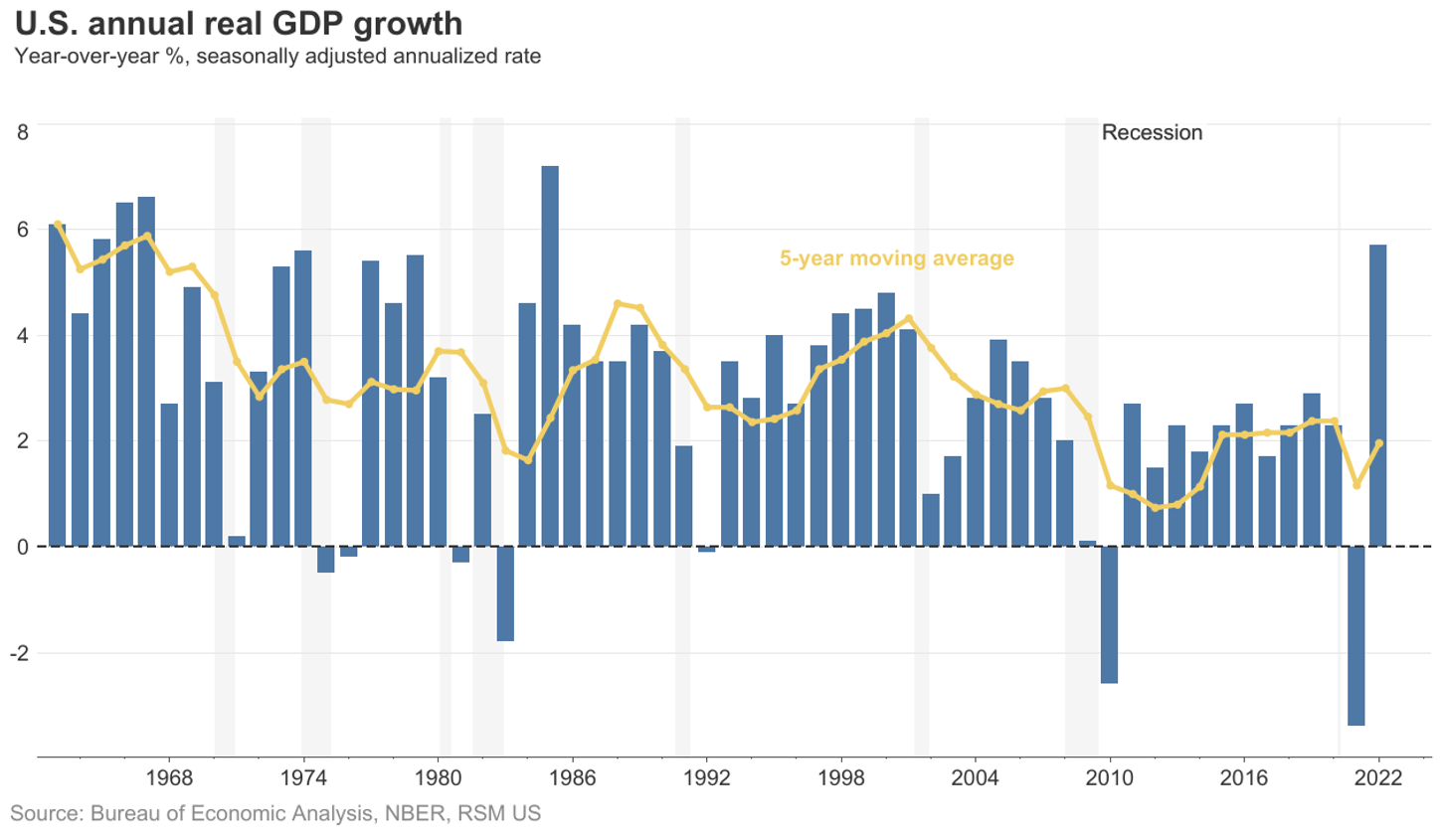

What about student debt?

It seems to have been declining since about 2010! Why? The government’s biggest student loan program is capped at $31,000, most people started hitting that max around 2010, the government never changed the cap, and the value of $31,000 goes down with inflation every year.

(does this prove that the root cause of rising college prices was government loans all along?)

Meanwhile, credit card debt, etc, are rounding errors in comparison. So the vibecession can’t be a debt trap.

The Brooklyn Theory Of Everything

In modern America, people in a tiny number of cities - NYC, SF, DC - dominate elite conversations. We have long since priced in that all the prestige information sources - New York Times, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, The New York Review Of Books - share a certain perspective. But even the alternative media that has done the most to popularize the idea of the modern economy as hellworld for the young - Chapo Trap House, Red Scare, etc - grew out of the same New York environment.

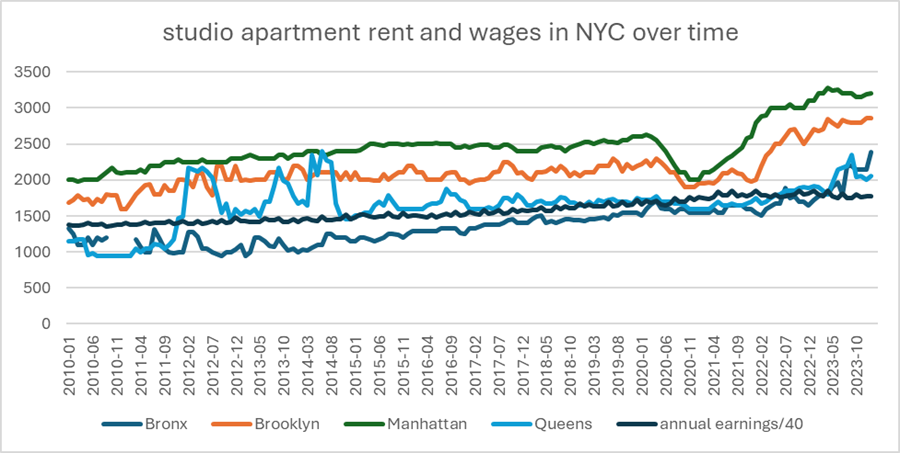

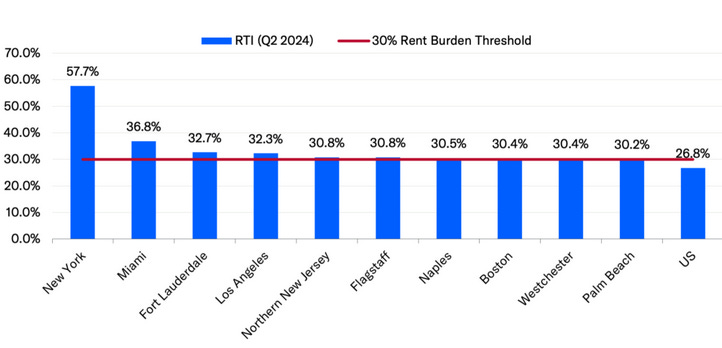

So how have rents changed in New York?

Surprisingly, they’ve done no worse than the US average. Aside from the post-pandemic spike, they tracked cost of living. And their post-pandemic spike is comparatively modest.

Does this disprove the Brooklyn Theory of Everything? Not necessarily. The new revised version says that the concentration of young elites and would-be elites in NYC and SF is itself a new phenomenon.

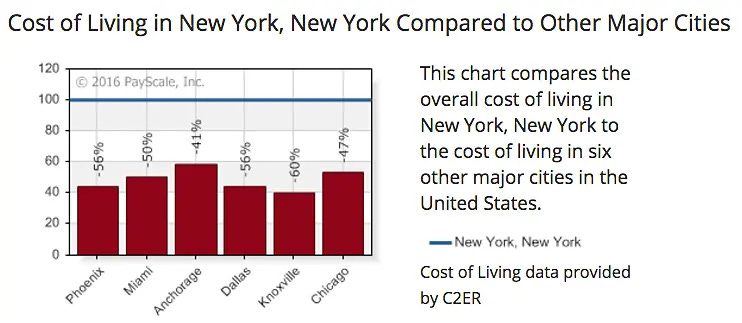

Since life in SF, DC, and NYC is especially pricy…

…someone who moves from a counterfactual life in Boston to New York City has effectively had rent increase from 30% to 58% of income, even before we get to the secular trend! Then these people think “My life and that of everyone I know is unaffordable! It must be a generational crisis!”

Then they write about it in the New York Times and The New Yorker, and their readers - including the average people who take the consumer sentiment surveys - believe the economy is uniquely awful.

This isn’t the same as saying “it’s all vibes, there’s no crisis”. The crisis is that young people who want to join the elite are being forced into places they can’t afford. Would-be financial elites must spend years of misery chasing a lottery ticket that might not pay off; would-be cultural elites face the same challenge, plus their economic situation may not improve even if they win the culturally-prestigious (but low-paying) positions they seek.

A natural test for this hypothesis would be to check economic sentiment in Brooklyn vs. the rest of the country. But this wouldn’t necessarily work: the hypothesis predicts that malaise will spread from Brooklyn to everywhere else.

More Work To Stay In The Same Place

Brenda Boomer applied to a local business she liked at age 18. She got hired, worked her way up from the bottom, and by age 35 she was a regional manager making $50,000 per year.

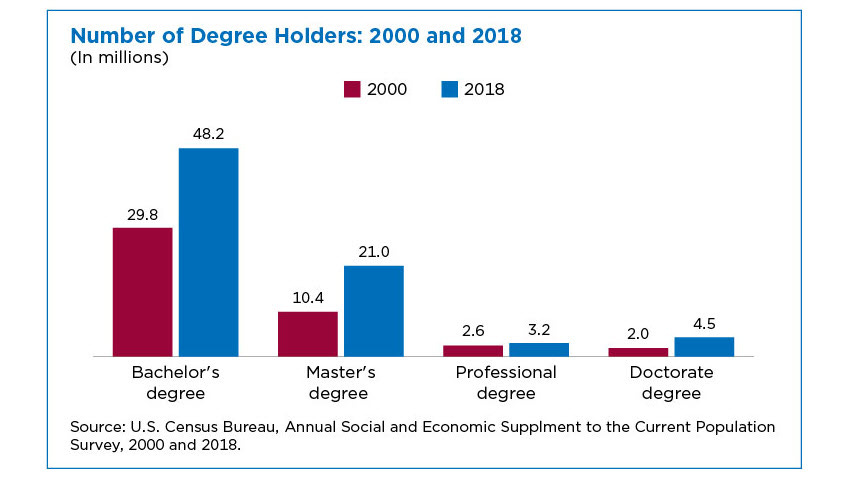

Martha Millennial lost her adolescence to endless lessons in Mandarin, water polo, and competitive debate, all intended to pad her college resume; her only break was the three months she spent building houses in Rwanda to establish her social justice credentials. She eventually got accepted to Penn and earned a 4.2 in her college classes, despite having to complete several of them remotely from the Google campus where she was doing a simultaneous internship. After graduation, she applied to twenty-eight grad schools but was rejected from all of them, so she instead got two half-time jobs, one as a waitress and one at a startup that pitched itself as “Uber for humidifiers”. The humidifier startup failed, reducing her equity to $0, but she had only been in it for networking anyway, and by attending industry conferences every weekend she had collected the right contacts to get a warm introduction to the vice-president of their biggest competitor, “Uber for dehumidifiers”. She joined the dehumidifier startup, rose to associate manager, bumped up against a local ceiling (“we don’t promote from inside”), and successfully got herself poached by an air purifier startup, where at age 35 she was a regional manager making $50,001 per year.

Technically Martha did better than Brenda at the same age. But she might still yearn for simpler times.

What causes this one? It must be something big: after all, we see the same trend in college admissions, job applications, and (really!) dating, where matches that used to happen naturally have turned to an endless grind through hundreds of rejections and near-misses. The most likely explanation is technology removing frictions: when it’s easy to apply en masse to every opportunity in the world, every opportunity in the world gets thousands of applicants. They search for the best based on formal qualifications, so the value of formal qualifications goes up, so there’s an increasing arms race to achieve them.

The only problem with this theory is that it doesn’t entirely match people’s complaints. They don’t complain that it was too hard to achieve their success, they complain that they are not achieving success, or that it feels hopeless. Speculatively, maybe people complain that they are not getting the level of success they expected based on their qualifications. That is, the same average-talent person is getting the same average-salary job they would have forty years ago. But since they have a masters’ degree and five internships and 12,000 LinkedIn contacts, they expected to get a better-than-average job. When they don’t, it feels like success slipping away.

Conclusion

Until now, we’ve tried to take disillusioned young people at their word. If instead we lean towards the economists, what might be ruining the vibes?

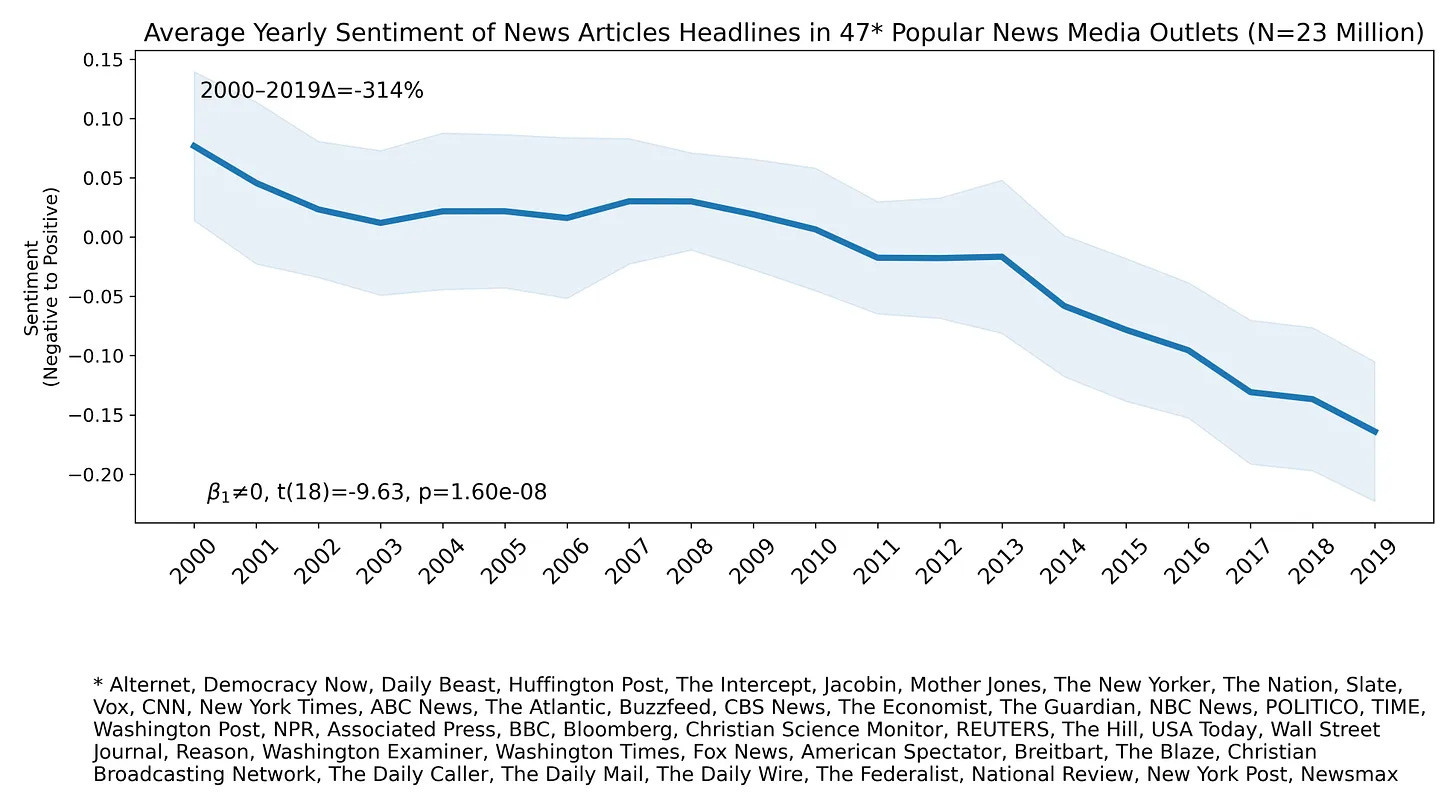

The obvious answer is increasing negative bias in the media.

This measure likely underestimates the trend towards negativity, because it only tracks a specific basket of media outlets. But the change could also have included viewers shifting consumption from more mainstream outlets towards more conspiratorial ones, including social media and blogs.

(my Substack is tagged Science, but I hear the real money is in the Health Politics tag, where top performers feature articles like The Great Alzheimers Scam And The Proven Cures They’ve Buried For Billions and Russian COVID Vaccines Caused Global Turbo Cancer Crisis)

So, is that all there is?

I think the strongest case for an economic crisis beyond vibes would be:

Because of decreasing application friction, any given opportunity requires more effort to achieve than in earlier generations. Although this can’t lower the average society-wide success level (because there are still the same set of people competing for the same opportunities, so by definition average success will be the same), it can inflict deadweight loss on contenders and a subjective sense of underachievement.

Because of concentration of jobs in high-priced metro areas, effective cost-of-living for people pursuing these jobs has increased even though real cost-of-living (ie for a given good in a given location) hasn’t. This effect is multiplied since it’s concentrated among exactly the sorts of elites most likely to set the tone of the national conversation (eg journalists).

Homeownership has become substantially more expensive since the pandemic (although the increase in rents is much less). This on its own can’t justify the entire vibecession, because most vibecessioneers are renters, and the house price change is relatively recent. But it may discourage people for whom homeownership was a big part of the American dream.

But even if these three factors are really making things worse, so what? Have previous generations never had three factors making things worse? Is our focus on the few things getting worse, instead of all the other things getting better or staying the same, itself downstream of negative media vibes?

I find this hard to believe, but am unable to find the smoking gun that definitively rules it out. I hope this post will serve as a starting point for further investigation: now that we’re all on the same page about which purported explanations don’t work, we can more fruitfully investigate alternatives.