Book Review: From Bauhaus To Our House

...

Like most people, Tom Wolfe didn’t like modern architecture. He wondered why we abandoned our patrimony of cathedrals and palaces for a million indistinguishable concrete boxes.

Unlike most people, he was a journalist skilled at deep dives into difficult subjects. The result is From Bauhaus To Our House, a hostile history of modern architecture which addresses the question of: what happened? If everyone hates this stuff, how did it win?

How Did Modern Architecture Start?

European art in the 1800s might have seemed a bit conservative. It was typically sponsored by kings, dukes, and rich businessmen, via national artistic guilds that demanded strict compliance with classical styles and heroic themes. The Continent’s new progressive intellectual class started to get antsy, culminating in the Vienna Secession of 1897. Some of Vienna’s avante-garde artists officially split from the local guild to pursue their unique transgressive vision.

The point wasn’t that the Vienna Secession itself was particularly modern…

…so much as that it cemented a new romantic vision of the Artist. The Artist was a genius, brimming with bold new ideas that the common people could never understand! The Artist defied the norms of bourgeois society! The Artist was part of some official collective with their own compound in a trendy part of the city! The compound produced manifestos explaining why their vision of Art was better than everyone else’s!

This romantic vision was so powerful that you could become a well-regarded artistic movement just by doing the collective, the compound, and the manifesto especially well. Whether or not you produced art was of secondary importance - the sort of question that a bourgeois who didn’t understand your true genius would ask.

At the same time, Europe’s intelligentsia was falling in love with socialism. There was an inevitable wave of new socialist art compounds, each writing a manifesto explaining why their new artistic movement was the one that truly threw off the shackles of capitalism and represented the proletariat.

Preeminent among these was Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in Germany in 1919. Their big idea was “starting from zero” - since all previous art had been contaminated by capitalism, we needed a hard reset where people started by (eg) contemplating what color and shape really were, then gradually building a new socialist art from the ground up. This new art must eschew ornamentation, associated as it was with kings and nobles who had money to spare on gold trim or sculpted curlicues. Real socialist art would be brutally functional, the sort of thing a poor worker might build. If this sounds harsh, remember that this was right after World War I, the old order stood infinitely discredited, and starting from zero must have seemed pretty appealing.

Maybe too appealing: the Bauhaus wasted no time in becoming a caricature of itself. Someone got into their head that pointed roofs “represented the crowns of the old nobility”; henceforward, all their buildings had flat tops (even though this was unsuited for the snowy German climate). Facades were fake, just like the fakeness of bourgeois propaganda; therefore true socialist buildings would show their innards as much as possible, with jutting pipes and undecorated structural supports.

Imagine for a moment the 2024 equivalent of Bauhaus. Someone has just started the woke artists’ collective, claiming to perfectly encapsulate all the principles of wokeism and be the wokest people around. What happens next? Obviously every other group of woke people accuse them of being racist, and they have bloody internecine feuds for the next twenty years, right?

Right. No sooner had Bauhaus developed their new socialist architecture designed to utterly remove all traces of bourgeois influence from design forever, then all the other socialist artists said: “I dunno, seems kind of bourgeois”:

The battle to be the least bourgeois of all became somewhat loony. For example, early in the game, in 1919, Gropius had been in favor of bringing simple craftsmen into the Bauhaus, yeomen, honest toilers, people with knit brows and broad fingernails who would make things by hand for architectural interiors, simple wooden furniture, simple pots and glassware. This seemed very working class, very nonbourgeois. He was also interested in the curvilinear designs of Expressionist architects such as Erich Mendelsohn. Mendelsohn’s dramatic curved shapes exploded all bourgeois conceptions of order, balance, symmetry, and rigid masonry construction. Yes—but a bit naïve of you all the same, Walter!

In 1922 the First International Congress of Progressive Art was held in Düsseldorf. This was the first meeting of compound architects from all over Europe. Right away they got down on the mat over this business of “nonbourgeois”. Theo van Doesburg, the fiercest of the Dutch manifesto writers, took one look at Gropius’ Honest Toilers and Expressionist curves and sneered and said: How very bourgeois. Only the rich could afford handmade objects, as the experience of the Arts and Crafts movement in England had demonstrated. To be nonbourgeois, art must be machine-made. As for Expressionism, its curvilinear shapes defied the machine, not the bourgeoisie. They were not only expensive to fabricate, they were "voluptuous" and "luxurious".

Van Doesburg, with his monocle and his long nose and his amazing sneer, could make such qualities sound bourgeois to the point of queasiness. Gropius was a sincerely spiritual force, but he was also quick enough and competitive enough to see that van Doesburg was backing him into a dreadful corner. Overnight, Gropius dreamed up a new motto, a new heraldic device for the Bauhaus compound: "Art and Technology — a New Unity!" Complete with exclamation point! There; that ought to hold van Doesburg and the whole Dutch klatsch. Honest toilers, broad fingernails, and curves disappeared from the Bauhaus forever.

But that was only the start. The definitions and claims and accusations and counteraccusations and counterclaims and counterdefinitions of what was or was not bourgeois became so refined, so rarefied, so arcane, so dialectical, so scholastic … that finally building design itself was directed at only one thing: illustrating this month’s Theory of the Century concerning what was ultimately, infinitely, and absolutely non-bourgeois.

My favorite story along these lines: 1930s German architect Bruno Taut built housing with a red front, a reference to the Red Front communist paramilitary group. There was fierce debate. On the one hand, this was a pretty sweet communism pun. On the other hand, red was a bright color, and bright colors seemed too much like ornament/decoration, which were known to be bourgeois. Taut’s side lost, and “henceforth white, beige, gray, and black became the patriotic colors, the geometric flag, of all the compound architects.”

So far this is what we would expect from an insular group of avante-garde socialists. The real question is - who hired these people? Often the answer was “nobody” - as long as you had a clever enough theory of the nonbourgeois, it didn’t really matter whether you built anything. Some of the most famous architects of this era never got a commission until late in their careers, or survived off a few commissions from friends and family.

Other times the answer was “socialist governments”. For example, the socialist party got elected to local government in the German city of Stuttgart in 1927, and rewarded socialist artists with contracts to build worker housing - the first of what would later be known as “commieblocks”.

Ironically, real workers hated the modernist styles, and could only be forced into them when there was nowhere else to go. The architects were unfazed. The Romantic ideal of the artist said that real artists considered their clients Philistines and paid no heed to their preferences; the less you cared about your clients’ opinion, the realer and more romantic an artist you were. There was a slight hiccup in adjusting this philosophy to socialism, but only slight: by this time, classical Marxist philosophy had already ceded to the Bolshevik idea of a “dictatorship of the proletariat” where communist-theory-educated elites needed to re-educate the workers into accepting their own class interests. Wolfe describes the overall effect in Stuttgart:

How did worker housing look? It looked nonbourgeois within an inch of its life: the flat roofs, with no cornices, sheer walls, with no window architraves or raised lintels, no capitals or pediments, no colors, just the compound shades, white, beige, gray, and black. The interiors had no crowns or coronets, either. They had pure white rooms, stripped, purged, liberated, freed of all casings, cornices, covings, crown moldings (to say the least), pilasters, and even the ogee edges on tabletops and the beading on drawers. They had open floor plans, ending the old individualistic, bourgeois obsession with privacy. There was no wallpaper, no drapes,= no Wilton rugs with flowers on them, no lamps with fringed shades and bases that look like vases or Greek columns, no doilies, knickknacks, mantelpieces, headboards, or radiator covers. Radiator coils were left bare as honest, abstract, sculptural objects. And no upholstered furniture with "pretty" fabrics. Furniture was made of Honest Materials in natural tones: leather, tubular steel, bentwood, cane, canvas; the lighter — and harder — the better. And no more "luxurious" rugs and carpets. Gray or black linoleum was the ticket.

And how did the workers like worker housing? Oh, they complained, which was their nature at this stage of history. At Pessac the poor creatures were frantically turning Corbu’s cool cubes inside out trying to make them cozy and colorful. But it was understandable. As Corbu himself said, they had to be "re-educated" to comprehend the beauty of the Radiant City of the future. In matters of taste, the architects acted as the workers’ cultural benefactors. There was no use consulting them directly, since, as Gropius had pointed out, they were as yet "intellectually undeveloped".

In fact, here was the great appeal of socialism to architects in the 1920s. Socialism was the political answer, the great yea-saying, to the seemingly outrageous and impossible claims of the compound architect, who insisted that the client keep his mouth shut. Under socialism, the client was the worker. Alas, the poor devil was only just now rising up out of the ooze. In the meantime, the architect, the artist, and the intellectual would arrange his life for him. To use Stalin’s phrase, they would be the engineers of his soul. In his apartment blocks in Berlin for employees of the Siemens factory, the soul engineer Gropius decided that the workers should be spared high ceilings and wide hallways, too, along with all of the various outmoded objects and decorations. High ceilings and wide hallways and "spaciousness" in all forms were merely more bourgeois grandiosity, expressed in voids rather than solids. Seven-foot ceilings and thirty-six-inch-wide hallways were about right for . . . re-creating the world.

How Did It Take Over The Academy?

A prophet is without honor in his own country - or, to put it another way, a disease rarely goes pandemic in the area where it evolved. You need a naive unexposed population before ideas can really explode. Enter the United States.

In the early 1900s, the US still had a colonial inferiority complex. Europe automatically had the best and classiest of everything: the best intellectuals, the best food, and definitely the best art. A few bold Americans tried to blaze their own cultural trail, but they were overwhelmed by the power of elite Europhilia.

After World War I, some Americans visited Europe and brought back reports that the Bauhaus was pretty cool. Some modern art museums did exhibitions on the Bauhaus. Everyone agreed that they were cooler and better than we were, but nothing really came of it.

Then the Nazis took power in Germany. The socialist Bauhaus architects fled the country. Many came to America, where we colonial yokels responded with star-struck awe. Wolfe, writing before political correctness limited our stock of acceptable metaphors, says:

The reception of Gropius and his confreres was like a certain stock scene from the jungle movies of that period. Bruce Cabot and Myrna Loy make a crash landing in the jungle and crawl out of the wreckage in their Abercrombie & Fitch white safari blouses and tan gabardine jodhpurs and stagger into a clearing. They are surrounded by savages with bones through their noses - who immediately bow down and prostrate themselves and commence a strange moaning chant: The White Gods! Come from the skies at last!

The worshipful colonials immediately gave them every prestigious architecture position in the country. Gropius got the department chair at Harvard. As for Mies, the last director of the Bauhaus collective in Germany:

[He] was installed as dean of architecture at the Armour Institute in Chicago. And not just dean; master builder also. He was given a campus to create, twenty-one buildings in all, as the Armour Institute merged with the Lewis Institute of Technology. Twenty-one large buildings, in the middle of the Depression, at a time when building had come almost to a halt in the United States - for an architect who had completed only seventeen buildings in his career - o white gods! Such prostration! Such acts of homage!

And so:

The teaching of architecture was transformed overnight. Everyone started from zero…all architecture became nonbourgeois architecture, although the concept itself was left discreetly unexpressed, as it were. The old Beaux-Arts traditions became heresy, and so did the legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright, which had only barely made its way into the architecture schools in the first place. Within three years, every so-called major American contribution to contemporary architecture . . . had dropped down into the footnotes.

I found this part of the book sudden and jarring. Okay, Americans have always had an unhealthy fascination with European culture - but, really? Everyone abandoned all previous forms of architecture within a three year period just because some cool Europeans showed up? I was left to hunt down hints to the broader story. Some of these come from elsewhere in the book, and some are my own speculation.

First, the Bauhaus promised architects a promotion from tradesman to intellectual. Some, like Frank Lloyd Wright, had already started such a transition. But the average architect was just someone who knew some stuff about stone and columns and stuff. Rich people would hire one to build them a cool villa, the architect would follow instructions and make whatever cool villa the rich person had requested, the rich person would pay them, and they would make a decent living. But modernism told architects that they were not only brilliant romantic Artists in the style of Van Gogh or Picasso - they were also intellectuals. They should be able to discourse on which styles were bourgeois, which expressed the true meaning of Light and Structure, and so on. Someone who wrote manifestos on the true meaning of Structure is automatically in the upper middle class; they get invited to cooler parties than somebody who just knows things about different types of stone. This was the Bauhaus’ offer to architects, and they leapt at the opportunity.

Second, the first crop of European modern architects were incredibly charismatic and persuasive people. Gropius’ nickname was “The Silver Prince”; Wolfe describes him as “irresistibly handsome to women, correct and urbane in a classic German manner, a lieutenant of cavalry during [World War I], decorated for valor, a figure of calm, certitude, and conviction at the center of the maelstrom … [he] seemed to be an aristocrat who through a miracle of sensitivity had retained every virtue of the breed and cast off all the snobberies and dead weight of the past”. Meanwhile, his colleague, born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, demanded that everyone refer to him as “Le Corbusier” (French for “The Crow-Like One”)1 as some sort of combination artistic pseudonym / branding / flex. How are normal humans supposed to compete with people like these?

Third, modern architecture benefited from that most reliable of vectors for any bad idea: activist college students:

Faculty members resisted the compound passion at their peril. Students were becoming unruly. They were drawing up petitions - manifestos in embryo. No more laying down laborious washes in China ink in the old Beaux-Arts manner! No more tedious Renaissance renderings! … and the faculties caved in … With the somewhat grisly euphoria of Savonarola burning the wigs and fancy dresses of the Florentine fleshpots, deans of architecture went about instructing the janitors to throw out all plaster casts of classical details, pedagogical props that had been accumulated over a half century or more.

At Yale, in the annual design competition, a jury always picked out one student as, in effect, best in show. But now the students rebelled. And why? Because it was written, in the scriptures, by Gropius himself: “The fundamental pedagogical mistake of the academy arose from its preoccupation with the idea of individual genius.” Gropius and Mies’ byword was “team” effort . . . at Yale, the students insisted on a group project, a collaborative design, to replace the obscene scramble for individual glory.

Fourth, and more speculatively (ie I’m making it up), maybe the first modern building in a city looks better than the nth? Imagine a city where most buildings look like this:

…and then right in the middle, for the first time, somebody builds one of these:

It must have been incredibly jarring and impressive, like an embassy from the future. Imagine that you’re Pepsi, Coke just built the glass building, and you’re still in the brick building. Doesn’t seem great.

Fifth, one of the morals I took from The Rise Of Christianity is that you’re more likely to win if you’re in the game. Paganism was just a set of tools for propitiating deities; Christianity was a missionary religion. Except at the very end (eg Emperor Julian), pagans didn’t think of themselves as proud pagans or try to convince others of paganism - so Christianity, which understood that it was competing with paganism and tried to win the competition, succeeded almost by default. In the same way, older styles of architecture were just sets of tools for making pretty buildings. Its practitioners didn’t originally think of themselves as “old-style architects” or care about converting anyone else. But modern architecture, with its manifestos and compounds and nonbourgeoisity, was absolutely an ideology, and understood perfectly well that it was at war with its predecessors. Some of the most ideological bits were filed off before it came to America. In Germany, Bauhaus architects had tried to adhere to a special Bauhaus diet invented by Walter Gropius - that didn’t last long. But it was still recognizably a warrior faith.

How Did It Get Clients?

This is the question asked in From Bauhaus To Our House's famous introductory passage:

O BEAUTIFUL, for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain, has there ever been another place on earth where so many people of wealth and power have paid for and put up with so much architecture they detested as within thy blessed borders today?

I doubt it seriously. Every child goes to school in a building that looks like a duplicating-machine replacement-parts wholesale distribution warehouse. Not even the school commissioners, who commissioned it and approved the plans, can figure out how it happened. The main thing is to try to avoid having to explain it to the parents.

Every new $900,000 summer house in the north woods of Michigan or on the shore of Long Island has so many pipe railings, ramps, hob-tread metal spiral stairways, sheets of industrial plate glass, banks of tungsten-halogen lamps, and white-cylindrical shapes, it looks like an insecticide refinery. I once saw the owners of such a place driven to the edge of sensory deprivation by the whiteness & lightness & leanness & cleanness & bareness & spareness of it all. They became desperate for an antidote, such as coziness & color. They tried to bury the obligatory white sofas under Thai-silk throw pillows of every rebellious, iridescent shade of magenta, pink, and tropical green imaginable. But the architect returned, as he always does, like the conscience of a Calvinist, and he lectured them and hectored them and chucked the shimmering little sweet things out [...]

I find the relation of the architect to the client today wonderfully eccentric, bordering on the perverse. In the past, those who commissioned and paid for palazzi, cathedrals, opera houses, libraries, universities, museums, ministries, pillared terraces, and winged villas didn’t hesitate to turn them into visions of their own glory...But after 1945 our plutocrats, bureaucrats, board chairmen, CEO’s, commissioners, and college presidents undergo an inexplicable change. They become diffident and reticent. All at once they are willing to accept that glass of ice water in the face, that bracing slap across the mouth, that reprimand for the fat on one’s bourgeois soul, known as modern architecture.

And why? They can’t tell you. They look up at the barefaced buildings they have bought, those great hulking structures they hate so thoroughly, and they can’t figure it out themselves. It makes their heads hurt.

But even though it’s the framing device of the book, it barely gets addressed.

One clue is that not everywhere went modern at the same rate. The average suburban house is still built in traditional styles, because home-buyers have no need to justify them to anyone but themselves. But corporations and governments have a more complicated mandate. When executive or bureaucrats make decisions, they’re supposed to be catering to more than their personal aesthetic taste. They’re supposed to be following best practices and doing what’s responsible, maybe as judged by a sort of “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” type of standard. In architecture, the responsible-person standard was for big institutions that needed buildings to convene a Selection Committee including some representatives of the institution and at least one prestigious architect. But the representatives of the institution were out of their depth, and the prestigious architect could usually bully them into submission. So modernism it was.

The problem was alienation - the people designing the buildings weren’t the ones residing in them - or, in many cases, even viewing them as they walked by. Wolfe thinks that the people with the most exposure were least happy with the results. Here’s his discussion of the Seagram Building, one of the first great International Style skyscrapers:

The one remaining problem was window coverings: shades, blinds, curtains, whatever. [Architect Ludwig] Mies would have preferred that the great windows of plate glass have no coverings at all. Unless you could compel everyone in a building to have the same color ones (white or beige, naturally) and raise them and lower them or open and shut them at the same time and to the same degree, they always ruined the purity of the design of the exterior. In the Seagram Building, Mies came as close as man was likely to realizing that ideal. The tenants could only have white blinds or shades, and there were only three intervals where they would stay put: open, closed, or halfway. At any other point, they just kept sliding […]

The office workers shoved filing cabinets, desks, wastepaper baskets, potted plants up against the floor-to-ceiling sheets of glass, anything to build a barrier against the panicked feeling that they were about to pitch headlong into the streets below. Above these jerry-built walls they strung up makeshift curtains that looked like laundry lines from the slums of Naples, anything to keep out that brain-boiling, poached-eye sunlight that came in every afternoon . . . and by night, the custodial staff, the Mieslings police, under strictest orders, invaded and pulled down these pathetic barricades thrown up against the pure vision of the Silver Prince. Eventually, everyone gave up and learned, like the haute bourgeoisie above him, to take it like a man.

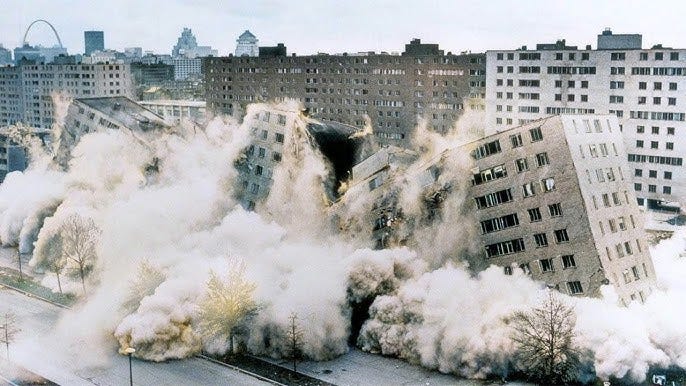

Predictably, modern architecture won its greatest victories among those who had the least opportunity to refuse: poor people in the projects. Wolfe writes especially of Pruitt-Igoe, a St. Louis public housing project designed by famous modern architect Minoru Yamasaki:

Yamasaki designed it classically Corbu [ie Le Corbusier], fulfilling the master’s vision of highrise hives of steel, glass, and concrete separated by open spaces of green lawn…On each floor there were covered walkways, in keeping with Corbu’s idea of “streets in the air”. Since there was no other place in the project in which to sin in public, whatever might ordinarily have taken place in bars, brothels, social clubs . . . now took place in the streets in the air. Corbu’s boulevards made Hogarth’s Gin Lane look like the oceanside street of dreams in Southampton, New York. Respectable folk pulled out, even if it meant living in cracks in the sidewalks. Millions of dollars and scores of commission meetings and task-force projects were expended in a last-ditch attempt to make Pruitt-Igoe habitable. In 1971, the final task force called a general meeting of everyone still living in the project. They asked the residents for their suggestions. It was a historic moment for two reasons. One, for the first time in the fifty-year history of worker housing, someone had finally asked the client for his two cents’ worth. Two, the chant. The chant began immediately. “Blow it . . . up! Blow it . . . up! Blow it . . . up!”

But Wolfe does admit that some rich people voluntarily selected, or even commissioned, modernist buildings. He blames trendiness. There was a pipeline from the architecture schools (now dominated by the modernists) to the architecture sections of newspapers and magazines (Wolfe blames Domus, House & Garden, and The New York Times Magazine in particular). Rich people would read the magazines, understand that modern architecture was “in”, and go with it so as to not feel “left behind”.

Wolfe doesn’t mention this - writing in 1981, how could he? - but this was the height of the age of expertolatry. See my reviews of Revolt Of The Public and Seeing Like A State for more. The concept of “the experts are a corrupt priesthood and you can safely ignore them” hadn’t really entered mass liberal consciousness. The idea that hard scientists were real experts but everyone else was just kind of faking it was decades in the future - and the Modernists were nothing if not good at faking the mantle of science and reason. This was mostly psychological - but also partly structural. There was no Internet. If you thought modern architecture was ugly, but all the experts said it was beautiful, there was no Twitter where you could shout your opinion under the cloak of anonymity. Every household got the same few TV channels and the same few magazines, and their architecture sections were all written by professionals who were singing the new style’s praises. So what are you going to do? Go to a cool party and shout “I think the style that all the experts say is the sign of an uneducated philistine is actually better”? Would you really?

Why Did It Stick Around?

Grant that all of the above modernism gave modernism the potential to be an exciting late ‘40s / early ‘50s fad. Why did it endure? Wolfe points to three culprits: loss of expertise, cost-cutting, and continued academic dominance.

To understand loss of expertise, let’s look at our Beaux-Arts building again:

All that ornament - the gilded plaster, the cast iron balcony, etc - required trained artisans. These artisans aren’t completely gone - some of them were no doubt involved in the recent restoration of Notre Dame and other similar projects. But they’re no longer organized into giant corporations capable of decorating a whole city. Wolfe:

To those philistines who were still so gauche as to say that the new architecture lacked the richness of detail of the old Beaux-Arts architecture … [the modernists] would say with considerable condescension: “Fine. You produce the craftsmen who can do that kind of work, and then we’ll talk to you about it. They don’t exist anymore.” True enough. But why? Henry Hope Reed tells of riding across West Fifty-third Street in New York in the 1940s in a car with some employees of E.F. Caldwell & Co, a firm that specialized in bronze work and electrical fixtures. As the car passed the Museum of Modern Art building, the men began shaking their fists at it and shouting: “That goddamn place is destroying us! Those bastards are killing us!” In the palmy days of Beaux-Arts architecture, Caldwell had employed a thousand bronzeurs, marble workers, model makers, and designers. Now the company was sliding into insolvency, along with many similar firms. It was not that craftsmanship was dying. Rather, the International Style was finishing off the demand for it, particularly in commercial construction.

Last time we discussed this, a commenter agreed this was a big problem:

I keep saying this when people bring this up: before I became a STEM parasite, I worked hammer and saw in a very rich and very busy area for custom buildings and houses, new and refurb and restore and regardless of what is said, the truth on the ground is:

Building buildings that look like how you want them to look is outrageously expensive and involves lots of skills that are uncommon in rich countries these days.

The only people that could timber frame were other third world imports that learned in the forest.

There was one person in my entire state-sized region that could do custom tile.

If we needed enamel restored on features in any way other than shitty, we had to ship them across the US.

If we needed certain types of trim or wall paper restored, we needed to import a guy from France.

If we needed certain types of cornice, we couldn't fucking do it at all because the last guy who knew how in the entire US died 10 years ago, and we would have needed to rederive the art from first principles at too great of an expense in time and money.

Cost-cutting was simple: cut out all the artisans, and buildings cost less. Sam Hughes at Works In Progress has done a great job showing that, contra the Baumolists, our modern industrial civilization could produce ornament cheaper than ever if we wanted to. But it’s even cheaper to not produce it. In the old days, cutting costs like this would have been unthinkable; your building would have stood out as an eyesore. But if every building is an eyesore, then spending extra on your building makes it look froo-froo, plus the extra money starts to seem irresponsible:

To those who complained that International Style buildings were cramped, had flimsy walls inside as well as out, and, in general, looked cheap, the knowing response was “These days it’s too expensive to build in any other style”. But it was not too expensive, merely more expensive. The critical point was what people would or would not put up with aesthetically. It was possible to build in styles even cheaper than the International Style. For example, England began to experiment with schools and public housing constructed like airplane hangars, out of corrugated medal tethered by guy wires. Their architects also said: “These days it’s too expensive to build in any other style.” Perhaps one day soon everyone (tout le monde) would learn to take this, too, like a man.

Finally, the academic architectural establishment was able to cancel anyone who proposed going back to the old ways. An architect who dared comply with a client’s request to add ornament would find themselves almost blacklisted. In 1954, architect Edward Stone2 had a falling out with modernists and started to add some ornament to his building. Not much - they still looked like concrete boxes. But some of them were ugly concrete boxes with circles on them:

According to Wolfe:

I can remember vividly the automatic sniggers, the rolling of the eyeballs, that mention of Stone’s [museum] set off at the time. The reviews of the architectural critics were bad enough. But not even such terms as “kitsch for the rich” and “marble lollipops” convey the poisonous mental atmosphere in which Stone now found himself. He was reduced, at length, to saying things such as “Every taxi driver in New York will tell you it’s his favorite building.” After so much! After a lifetime! - to be hounded, finally, to the last populist refuge of a Mickey Spillane or a Jacqueline Susann . . . O Lord! Anathema!

One will note that Stone’s business did not collapse following his apostasy, merely his prestige. [His new buildings] did wonders for his practice in a commercial sense. After all, the International Style was well hated even by those who commissioned it. There were still others ready to go to considerable lengths not to have to deal with it in the first place. They were happy enough to find an architect with modernist credentials, even if they had lapsed. But in terms of his reputation within the fraternity, Stone was poison. He had removed himself from the court. He was out of the game.

Wolfe recalls an incident from the beginning of his own career as an architectural journalist:

I can remember writing a piece for the magazine Architecture Canada in which I mentioned [heretical architect Eero] Saarinen in terms that indicated the man was worthy of study. I ran into one of New York’s best-known architectural writers at a party, and he took me aside for some fatherly advice.

“I enjoyed your piece,” he said, “and I agreed with your point, in principle. But I have to tell you that you are only hurting your cause if you use Saarinen as an example. People just won’t take you seriously. I mean, Saarinen . . . “

I wish there were some way I could convey the look on his face. It was that cross between a sneer and a shrug that the French are so good at, the look that says the subject is so outre, so infra dig, so de la boue, one can’t even spend time analyzing it without having some of the rubbish rub off.

Another anecdote, this time on hotel architect Morris Lapidus3:

In 1970, Lapidus’ work was selected as the subject of an Architectural League of New York show and panel discussion entitled “Morris Lapidus: Architecture Of Joy”. Ordinarily this was an honor. In Lapidus’ case it was hard to say what it was. I was asked to be on the panel - probably, as I look back on it, with the hope that I might offer a “pop” perspective (This word, “pop”, had already come to be one of the curses of my life). The evening took on an uneasy, rather camp atmosphere - uneasy, because Lapidus himself had turned up in the audience. His work was being regarded not so much as architecture as a pop phenomenon, like Dick Tracy or the Busby Berkeley movies. I kept trying to put in my two cents’ worth about the general question of portraying American power, wealth, and exuberance in architectural form. I might as well have been talking about numerology in the Yucatan. The initial camp rush had passed, and the assembled architects began to give Lapidus’ work a predictable going-over. At the end, Lapidus himself stood up and said that the Soviets had once asked him to come to Russia and design some public housing and that they had been highly pleased with the results. Then he sat down. Nobody could quite figure it out, unless he was making a desperate claim of redeeming social significance . . . that might make him less radioactive.

What Happened To It?

One of my pet peeves is that when I tell a classy person I don’t like modern architecture, they’ll correct me - “Oh, I’m sure you don’t like Brutalism. But it’s unfair to hold that against the whole area. Why, surely even someone like you can appreciate the unique beauty of a von Shmendenstein, a Dazervaglik, or a Mihokushino.” Then I sheepishly admit that I’ve never heard of any of those people, and maybe I was overly hasty, and I should have been more careful and done my homework. They pat me on the head and say it’s fine.

Then I’d go home and look it up and all those people’s buildings would be hideous.

Wolfe earns my affection by calling this out. He admits that c. 1970 modern architecture split into a dizzying variety of styles - but also, that those styles were all similar and bad.

By c. 1970, heretics in the style of Stone and Saarinen had mostly lost. How do you attack an invincible consensus? By claiming to be even more orthodox than your fellows. This was the insight of an architect named Robert Venturi, who spent most of his time writing incredibly erudite manifestos about how modern architecture wasn’t modern enough.

Wolfe ties this to the contemporaneous rise of pop art. Modern art and architecture were founded in the rejection of bourgeois notions of beauty, in favor of a faux-proletarian idea of simplicity and scientificness. But, Venturi pointed out, proletarians were kind hard to find in c. 1970 America. Grounding your class analysis in a non-existent proletariat seemed kind of out-of-touch, and so - perhaps - bourgeois. Who actually existed? The middle class. And what did the middle class like? Mass market consumer slop. Therefore, the true foundation of Art should be mass market consumer slop. Of course, since artists are superior to the middle class, it should be some sort of extremely complicated reference to mass market consumer slop which makes it clear that the artist themselves is infinitely above such things (but also, what if they weren’t above it, because they were so in-touch with normal people (but also, obviously they’re infinitely above it (but also, what if they weren’t))) . . . and so on. This tendency eventually became postmodernism with all its layers of irony and self-reference.

In architecture, postmodernism relaxed the constraint that every building had to be a box, in favor of buildings that were “playful” and tried to “undermine” traditional notions of form and shape:

Postmodern buildings were allowed to include some traditional elements and ornamentation, but only to refer to them ironically, confuse people about them, or mock them.

Postmodern skyscrapers were still mostly ugly boxes - but with one weird feature, to show how playful they were being:

Wolfe has a certain horrified admiration for Venturi. He thinks he was a master at going right up to the brink of heresy, jumping back before anyone could accuse him of anything, rushing back to the brink immediately, and cloaking his real opinions under so many layers of irony that nobody knew what to do with him. Since at this point architecture was mostly a manifesto game, and Venturi’s manifestos were cleverer than anyone else’s, he became a leader of the field:

[His manifestos said] “I like complexity and contradiction in architecture. I do not like the incoherence or arbitrariness of incompetent architecture nor the precious intricacies of picturesqueness or expressionism.” Translation: I, like you, am against the bourgeois (pictureseque, precious, intricate, arbitrary, incoherent, and incompetent. Moreover, I, like you, have no interest in the merely eccentric (expressionism in the Saarinen or Mendelsohn manner). Venturi continues: “Instead, I speak of a complex and contradictory architecture based on the richness and ambiguity of modern experience, including that experience which is inherent in art.” This turns out to be the most important sentence in the book. Including that experience which is inherent in art.

Translation: I, like you, am working here within these walls. I am still a member of the compound. Don’t worry, the complexities and contradictions I am going to show you, with their “messy vitality”, are not going to be drawn from the stupidities of the world outside (exception, occasionally, for playful effects) but from our own experience as progeny of the Silver Prince, from that experience which is inherent in art: namely, the esoteric lessons of Mies, [Le Corbusier], and Gropius concerning modern architecture itself. I am going to show you how to make architecture that will amuse, delight, enthrall other architects. This, then was the genius of Venturi. He brought modernism into its Scholastic age. Scholasticism in the Dark Ages was theology to test the subtlety of other theologians. Scholasticism in the twentieth century was architecture to test the sublimity of other architects.

Not for a moment did Venturi dispute the underlying assumptions of modern architecture: namely, that it was to be for the people, that it should be nonbourgeois and have no applied decoration, that there was a historical inevitability to the forms that should be used, and that the architect, from his vantage point inside the compound, would decide what was best for the people and what they inevitably should have.

After Venturi opened the floodgates, a whole host of new schools arose, including:

The Whites, Le Corbusierian fundamentalists, named after their conviction that all buildings should be white:

The Grays, followers of Venturi, named after their disagreement with the belief that all buildings should be white, and for sometimes creating gray buildings:

The Rationalists, who thought that any architecture created while the bourgeois class existed was inherently bourgeois, and therefore architecture had to hearken back to forms that existed before the rise of capitalism in the 1700s - but strip them of ornamentation to the point that they looked exactly like modern buildings to the untrained eye. They were famous for calling every other style of architecture “immoral”:

This was the height of the revolt against Modernism when Wolfe was writing in 1981; I can’t comment on what (no doubt amazing and brilliant) schools have arisen since then.

What Should We Make Of All This?

Most books on modern art try to convince you that the Emperor’s clothes are splendid and made of the finest silks. I appreciate Wolfe’s commitment to not doing that here. He didn’t give an inch.

Still, I would like to read another book by someone equally talented who gives . . . well, exactly one inch. They don’t need to praise modern architecture’s beauty and brilliance - in fact, I would rather they didn’t. I want a book by someone who is overall skeptical, who at least has as a hypothesis “this is all an elite signaling game gone tragically wrong” - but who’s also willing to explain what the modern architects thought they were doing, in their own minds.

Wolfe does this only very occasionally, to mock them. He’ll show us a picture of some hideous concrete cube, and say that the architect thought he was “reinventing the idea of light” or something, and that all the other architects praised the building for reinventing the idea of light, and that the architect got a prestigious award for reinventing the idea of light. I would like to read a book by somebody who - while gently holding onto the possibility that it’s all balderdash - tells us what this architect meant by “reinventing the idea of light”, tries their best to help normal people grok it, and comes to a conclusion about whether light has indeed been reinvented. I haven’t found a book like this yet. Everyone either waxes rhapsodic about how amazing the light is, or dismisses the whole thing as trash.

Still, I only want this for my own edification. I think we can condemn modern architecture without it.

Whether or not there’s some sophisticated perspective from which modern architecture appears brilliant, most people don’t have that perspective. Polls show most people hate it and prefer the old stuff. A quick look at social media will confirm that most people hate it and prefer the old stuff. So who cares whether, if they got twenty years of training in the intricacies of how Venturi is subtly citing Gropius but also subtly undermining him, they would consider it really clever? They’re not going to get those twenty years of training! They have to walk past the building every day! I’m prepared to believe that the great modern buildings have (for example) solved structural support in some elegant and surprising way, or that their minimalist aesthetic does more with a tiny number of elements than people would have thought possible - but these shouldn’t be the most important selection criteria for buildings that shape how people view their communities and their lives.

Why should our entire built environment be optimized to amuse a sliver of one percent of the population, even granting that it amuses them very effectively? People mock kitsch art as “the kind of picture you’d put up at the dentist’s office”. But it serves this purpose fine. People don’t want to go to the dentist’s office and see a picture of the Virgin Mary in a vat of urine. You should keep the avant-garde stuff for the museums and let ordinary people living their ordinary life see normal pretty things.

So I think it’s fine to hate modern architecture. If someone else says it reinvents the idea of light, just tell them that’s really cool for the 1% of the population who notice it, but that the rest of the world deserves buildings they don’t hate.

Wolfe doesn’t chart a path to how things could improve, and lists many obstacles to change. My hope is AI + 3D printing. AI has already ensured that people with no artistic talent can produce the kind of images they want, rather than the kinds that tastemakers say are most tasteful. And it potentially sidesteps the problem of lost expertise. I look forward to a day when people can describe their dream buildings and technology can make it happen. I’ve seen a thousand utopias pictured on the covers of a thousand sci-fi books, and not one of them has been made of unadorned concrete boxes.

Until then, I think it’s useful just to call attention to the problem. People are bad at protesting when they think they’re the lone dissenter. If dissent becomes common knowledge, maybe those Selection Committees will go differently. Maybe when the businessmen or the community stakeholders say something, and the prestigious architect sneers at them and says “Oh, so you want it to be picturesque? You love kitsch? Do you go home to your McMansion every night?”, they will draw inspiration from a very wise meme format and answer:

I can’t help thinking of this as the adult male version of “Mooom, stop calling me Brittany, I already told you my new name is Raven!”

Note nominative determinism

Ibid