Book Review: The Rise Of Christianity

...

The rise of Christianity is a great puzzle. In 40 AD, there were maybe a thousand Christians. Their Messiah had just been executed, and they were on the wrong side of an intercontinental empire that had crushed all previous foes. By 400, there were forty million, and they were set to dominate the next millennium of Western history.

Imagine taking a time machine to the year 2300 AD, and everyone is Scientologist. The United States is >99% Scientologist. So is Latin America and most of Europe. The Middle East follows some heretical pseudo-Scientology that thinks L Ron Hubbard was a great prophet, but maybe not the greatest prophet.

This can only begin to capture how surprised the early Imperial Romans would be to learn of the triumph of Christianity. At least Scientology has a lot of money and a cut-throat recruitment arm! At least they fight back when you persecute them! At least they seem to be in the game!

Rodney Stark was a sociologist of religion. He started off studying cults, and got his big break when the first missionaries of the Unification Church (“Moonies”) in the US let him tag along and observe their activities. After a long and successful career in academia, he turned his attention to the greatest cult of all and wrote The Rise Of Christianity. He spends much of it apologizing for not being a classical historian, but it’s fine - he’s obviously done his homework, and he hopes to bring a new, modern-religion-informed perspective to the ancient question.

So: how did early Christianity win?

Slowly But Steadily

Previous authorities assumed Christianity spread through giant mass conversions, maybe fueled by miracles. Partly they thought this because the Biblical Book of Acts describes some of these. But partly they thought it because - how else do you go from a thousand people to forty million people in less than 400 years?

Stark answers: steady exponential growth.

Suppose you start with 1,000 Christians in 40 AD. It’s hard to number the first few centuries’ worth of early Christians - they’re too small to leave much evidence - but by 300 AD (before Constantine!) they’re a sizeable enough fraction of the empire that some historians have tentatively suggested a 10% population share. That would be about 6 million people.

From 1,000 to 6,000,000 in 260 years implies a 40% growth rate per decade. Stark finds this plausible, because it’s the same growth rate as the Mormons, 1880 - 1980 (if you look at the Mormons’ entire history since 1830, they actually grew a little faster than the early Christians!)

Instead of being forced to attribute the Christians’ growth to miracles, we can pin down a specific growth rate and find that it falls within the range of the most successful modern cults. Indeed, if we think of this as each existing Christian having to convert 0.4 new people, on average, per decade, it starts to sound downright do-able.

Still, how did the early Christians maintain this conversion rate over so many generations?

Through The Social Graph

This is another of Stark’s findings from his work with the Moonies.

The first Moonie in America was a Korean missionary named Young Oon Kim, who arrived in 1959. Her first convert was her landlady. The next two were the landlady’s friends. Then came the landlady’s friends’ husbands and the landlady’s friends’ husbands’ co-workers. That was when Stark showed up. “At the time . . . I arrived to study them, the group had never succeeded in attracting a stranger.”

Stark theorized that “the only [people] who joined were those whose interpersonal attachments to members overbalanced their attachments to nonmembers.” I don’t think this can be literally correct - taken seriously, it implies that the second convert could have no other friends except the first, which would prevent her from spreading the religion further. But something like “your odds of converting are your number of Moonie friends, divided by your number of non-Moonie friends” seems to fit his evidence.

History confirms this story. Mohammed’s first convert was his wife, followed by his cousin, servant, and friend. Joseph Smith’s first converts were his brothers, friends, and lodgers. Indeed, in spite of the Mormons’ celebrated door-knocking campaign, their internal data shows that only one in a thousand door-knocks results in a conversion, but “when missionaries make their first contact with a person in the home of a Mormon friend or relative of that person, this results in conversion 50% of the time”. 1

This theory of social-graph-based-conversation was controversial when Stark proposed it, because if you ask cultists retrospectively, they’ll usually say they were awed by the beauty of the sacred teachings. But Stark says:

I knew better, because we had met them well before they had learned to appreciate the doctrines, before they had learned how to testify to their faith, back when they were not seeking faith at all. Indeed, we could remember when most of them regarded the religious beliefs of their new set of friends as quite odd. I recall one who told me that he was puzzled that such nice people could get so worked up about “some guy in Korea” . . . Then, one day, he got worked up about this guy too.

Through Jews And Weajoos

Jews were scattered across the Mediterranean even before the fall of the Temple. I don’t know why. We Jews tell ourselves that we left Israel only after the Romans kicked us out. But Stark cites plenty of historians who argue that no, it was well before that. Around the time of Christ, there were a million Jews in Israel and five million in the Diaspora, especially Alexandria, Antioch, Anatolia, and Rome.

What were these Jews’ spiritual lives like? Without hard evidence, Stark supposes they were marginal. Throughout history, Jews have succeeded at keeping the Law only within tight-knit communities. If you want to keep kosher, it helps to have everyone around you keeping kosher and a local kosher butcher. If you want to keep the Sabbath, it helps to have an eruv and a synagogue within walking distance. But even more than that, the Law is strange and complicated, and unless everyone around you follows it too, you are likely to slip.

Thus, when Jews were first emancipated and allowed to live among Gentiles in the 18th-19th centuries, a split emerged in the Jewish community. Those Jews who stayed in the ghettos and shtetls - or who founded new self-imposed-quasi-ghettos like Crown Heights - remained Orthodox. Those Jews who mingled with the Gentiles cast off the more difficult rules and became Reform. Only a sliver of Modern Orthodox remained in the middle, often with abysmal attrition rates.

Stark asks whether the first great intermingling of Jews and Gentiles had the same effect. While the Jews in Palestine stayed religious and laid the foundations for the Rabbinic Judaism of future centuries, the Jews in the Diaspora - did what? Presumably Hellenized into some sort of semi-assimilated proto-Reform movement. Although we have limited historical evidence about these Jews’ religious behavior, we know they spoke Greek and not Hebrew (otherwise why would they need the Septuagint?) and that many of them took Greek names.

Reform Judaism is unstable. The Law of Moses is central to the Jewish faith; relax it too much, and believers can justly wonder what’s left. In America, Reform Jews are over-represented not only among atheists and agnostics, but among every cult under the sun. 33% of American Buddhists come from a Jewish background, and even the Moonies were 30% Jewish at one point! (they’re now down to 6%)

As the Jews were assimilating into Greeks, some Greeks were assimilating into Judaism. They were impressed enough with monotheism and the Jews’ upright behavior to adopt some of the rituals, but they couldn’t take the final step and circumcise themselves. Instead, they hung around the fringes of Jewish society, admiring it from without. The Bible and the historical record call them “God-fearers”, but by analogy I can’t help but think of them as “weajoos”. These weajoos would have been easy prey for the first semi-Jewish sect to shed the circumcision requirement and explicitly pivot away from being an ethnic religion.

The Apostles and other early Christians, leaving Palestine to minister to the wider world, would have made use of existing Jewish networks and connections. They would have found themselves in the middle of the spiritually-disaffected, half-assimilated pseudo-Reform Jewish communities of the Roman world, plus their half-assimilated-the-other direction Greek hangers-on. They would have preached that Judaism was basically true, but that you can drop the restrictive Law of Moses and avoid getting circumcised. They would have sliced through the cultural angst of these in-between communities, saying that Jews could join together with Gentiles in a big friendly tent under the leadership of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Here, says Stark, were the early Christians’ first few million converts.

Because, I Regret To Inform You, The Pronatalists Are Right About Everything

We found above that the Christian population needed to grow at 40% per decade, and assumed this meant conversion. But you could also do this through a fertility advantage. If a generation lasts thirty years, and Christians have 3x more children than pagans per generation, they can get 40%/decade growth without converting anyone at all. In reality, it was probably a mix: some conversion plus some fertility advantage.

Here I start to worry that some right-wing pronatalist organization bribed Rodney Stark to abandon his usual scholarly attitude and write some kind of over-the-top pronatalist fanfic. I was waiting for the part where the eagle named MORE BIRTHS perches on the blackboard and the childfree professor was tossed into the lake of fire for all eternity. Still, let’s take it at face value and see what the fanfic has to say.

By the Imperial era, Roman fertility was plummeting. Partly this was because the Romans practiced sex-selective infanticide, there were 130 men for every 100 women, and so many men would never be able to find a wife. But partly this was because the men who could find wives dragged their feet. (Male) Roman culture took it as a given that women were terrible, that you couldn’t possibly enjoy interacting with them, and that there was no reason besides duty that you would ever marry one.

In 131 BC, the Roman censor Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus2 proposed that that the senate make marriage compulsory because so many men, especially in the upper classes, preferred to stay single. Acknowledging that “we cannot have a really harmonious life with our wives”, the censor pointed out that "since “we cannot have any sort of life without them,” the long term welfare of the state must be served”… As Beryl Rawsom has reported, “one theme that recurs in Latin literature is that wives are difficult and therefore men do not care much for marriage.”

The Romans understood that this was long-term fatal for their empire, and tried all sorts of schemes to increase family formation. In the mid-first-century BC, Cicero re-proposed Metellus’ scheme to make marriage compulsory, but it failed once again. Augustus contented himself with punitive taxes and second-class citizenship for unmarried and childless couples, combined with subsidies and affirmative action for men with at least three children.

Formal and informal social pressure eventually convinced most Roman men to take wives, but no amount of love or money could make them have children. Dense cities discouraged large families, Roman children were expensive (nobles would have to spend immense effort and political favors grooming them for high positions), and (the scourge of all nobilities) too many children risked splitting the inheritance. Also, if you had a girl you’d probably just kill her (she would consume resources without continuing the family line), and half of children died before adulthood from some disease or another anyway. It was just a really bad value proposition.

Nor did the sex drive force the matter. Horny Roman men had their choice of a wide variety of male and female slaves and prostitutes - despite Augustus and his spiritual heirs’ fuming about monogamy, this was never really enforced on the male half of the population. When men did have sex with women, it was usually oral or anal sex, specifically to avoid procreation. When they did have vaginal sex, they had a wide variety of birth control methods available, including the famous silphium but also proto-condoms and spermicidal ointments. If a child was conceived despite these efforts, abortion was common albeit unsanitary (maternal death rates were extremely high, but this was not really a deal-breaker for the Roman men making the decision). If a baby was born in spite of all this, infanticide was legal and extremely common:

Far more babies were born than were allowed to live. Seneca regarded the drowning of children at birth as both reasonable and commonplace. Tacitus charged that the Jewish teaching that it is “a deadly sin to kill an unwanted child” was but another of their “sinister and revolting practices” . . . not only was the exposure of infants a common practice, it was justified by law and advocated by philosophers.”

Christians followed the opposite of all these practices.

They recommended that men love their wives, and held this as a plausible and expected outcome. This was not exactly unprecedented, but it was a dramatic reversal of Roman custom. From Ephesians 5:

Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her to make her holy, cleansing her by the washing with water through the word, and to present her to himself as a radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish, but holy and blameless. In this same way, husbands ought to love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. After all, no one ever hated their own body, but they feed and care for their body, just as Christ does the church — for we are members of his body. “For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.” This is a profound mystery — but I am talking about Christ and the church. However, each one of you also must love his wife as he loves himself, and the wife must respect her husband.

The Christians banned adultery (and, unlike the Roman bans, gave it teeth), meaning that married men who wanted sex had no choice but to go to their wives. They held that sex had to be procreative, banning anal sex, oral sex, homosexual sex, and birth control. And obviously they banned infanticide (many of these bans weren’t active decisions, but carry-overs from the movement’s Jewish roots).

Also, I regret to say I fell for the liberal meme that Republicans tricked Christians into being anti-abortion in 1960, and previous generations of Christian had thought abortion was fine. This is absolutely not true. The Didache, the first Christian text outside the New Testament itself, probably dating from about 90 AD, says that “Thou shalt not murder a child by abortion nor kill them when born”. The second-century church father Athenagoras wrote:

We say that women who use drugs to bring on an abortion commit murder, and will have to give an account to God for the abortion . . . for we regard the very foetus in the womb as a created being, and therefore an object of God’s care . . . and [we do not] expose an infant, because those who expose them are chargeable with child-murder.

The end result is that while pagans delayed marriage, cheated, had nonprocreative sex, used birth control, performed abortions, and committed infanticide, Christians did none of these things.

This section gave me a new appreciation for conservative Christian purity culture: it was obviously suited for the environment in which it evolved, and it’s also obvious why its founders would etch it so deeply into its memetic DNA that it’s still going strong millennia later.

But I’ll end this section with a note of caution - I’m not sure how relevant any of this is. Stark refuses to speculate on pagan vs. Christian fertility rates, but when I look up modern scholarship, they reasonably point out that pagan rates must have been around “replacement”, given that the Roman population stayed steady (or slowly increased) for hundreds of years. “Replacement” is in quotes because Romans were constantly dying of plague, warfare, fire, and a million other causes; since only a third to half of people survived to reproduce, “replacement” here is something like 4-6 children per women. This doesn’t sound like the antinatalist disaster Stark describes!

I think Stark is mostly talking about Roman elites - the group who Augustus kept pestering to have at least three children - and more broadly about the urban population. These people were constantly dying and being replaced by commoners and villagers.

Early Christianity was primarily an urban and upper-class movement (does this surprise you? Stark urges us to think of modern cults and new religions, like American Buddhism, which predominantly recruit disillusioned children of the upper classes). So perhaps it did better than its urban upper-class pagan comparison group. Still, since the urban upper-class pagans were constantly being replaced by village lower-class pagans as soon as they died out, how much, in numerical terms, can this contribute to Christianity’s growth?

A possible synthesis: if you imagine a city as having a constant population (because it’s walled, plus its hinterland can only support a certain number of non-food-producing urbanites), and villagers as replacing urbanites on a one-to-one basis as they die, then greater Christian urban fertility rates can at least contribute to the cities and upper classes becoming Christian. And once the cities and upper classes are Christian, you get Constantine, and the lower classes can be forced to comply. Remember, “pagan” originally meant “rural”!

Because Where Women Go, Men Will Follow

One thing Stark did not mention discovering in his study of cults, but which I have heard anecdotally - a lot of male cult members join because the cult has hot girls. This seems to have been a big factor in the spread of early Christianity as well.

Stark collects various forms of evidence that early Christians were predominantly women. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans greets thirty-three prominent Christians by name, of whom 15 were men and 18 women; if (as seems likely) men were more likely to become prominent than women, this near-equality at the upper ranks suggests a female predominance at the lower. A third-century inventory of property at a Christian church includes “sixteen men’s tunics and eighty-two women’s tunics”. The book quotes historian Adolf von Harnack, who says:

[Ancient sources] simply swarm with tales of how women of all ranks were converted in Rome and in the provinces; although the details of these stories are untrustworthy, they express correctly enough the general truth that Christianity was laid hold of by women in particular, and also that the percentage of Christian women, especially among the upper classes, was larger than that of men.

Why were women converted in such disproportionate numbers? Again, Stark’s sociological background serves him well: he is able to find reports of the same phenomenon in modern religions:

By examining manuscript census returns for the latter half of the nineteenth century, Bainbridge (1983) found that approximately two-third of the Shakers were female. Data on religious movements included in the 1926 census of religious bodies show that 75% of Christian Scientists were women, as were more than 60% of Theosophists, Swedenborgians, and Spiritualists. The same is true of the immense wave of Protestant conversions taking place in Latin America.

But along with a general tendency for women to convert, Stark notes that Christianity was especially attractive to women. The pagan world treated women as their husbands’ property, and not particularly well-liked property at that. The book cites the Athenian laws as typical:

The status of Athenian women was very low. Girls received little or no education. Typically, Athenian females were married at puberty and often before. Under Athenian law, a woman was classified as a child, regardless of age, and therefore was the legal property of some man at all stages of her life. Males could divorce by simply ordering a wife out of the household. Moreover, if a woman was seduced or raped, her husband was legally compelled to divorce her. If a woman wanted a divorce, she had to have her father or some other man bring her case before a judge. Finally, Athenian women could own property, but control of the property was always vested in the male to whom she “belonged”.

Meanwhile, Christian woman had relatively high status, sometimes rising to the position of deacon within a church. Christian men were ordered to treat their wives kindly, were prohibited from cheating on them, and mostly could not divorce. Christianity, unlike paganism, did not especially pressure widows to remarry (important since a remarrying widow lost all her property to her new husband). Christian women were only a third as likely as Roman women to be married off before age 13. Women noticed all these benefits and flocked to Christianity.

Aside from all of this, the Romans were practicing sex-selective infanticide, reducing their female numbers still further, and making the Christians even more proportionally female-heavy. If the Christians, like many modern cults, were 65% female, and the Romans (as some sources attest) were about 40 - 45% female, this is a pretty profound difference.

The Romans grumbled about marriage, but in the end most Roman men did want wives (if only to avoid government penalties). But 1.4 men per women - maybe even less among the upper classes - puts young men seeking wives in a difficult situation (for comparison, modern San Francisco is only 1.05 men per women, and dating is already hell). To any remotely heterosexual Roman men, the 65% female Christian community must have started looking pretty good.

Meanwhile, the Christians had the opposite problem: too many women, not enough men. There’s an obvious solution, and it sounds like the pagans and Christians had also figured it out: From 1 Peter 3:

Wives ... submit yourselves to your own husbands so that, if any of them do not believe the Word, they may be won over without words by the behavior of their wives, when they see the purity and reverence of your lives.

History records many such intermarriages, almost always ending with the conversion of the pagan husband. If you are a Christian of English descent, you may owe your religion to Queen Bertha of Kent, who convinced her husband, one of the early Anglo-Saxon kings, to take her faith.

But Ruxandro Teslo has a great post reviewing the work of historian Michele Salzman, who disagrees with all of this. Salzman has a database of 400 aristocratic Romans during the 4th century period of Christianity’s fastest growth. She finds few intermarriages, few examples of women converting their husbands, and equal (or slightly male-biased) conversion ratios. Granted, this is only a small sample from one period. But it makes us question how good our evidence really is.

Doesn’t all this hinge on one passage from Paul which, technically, named more men than women, plus one inventory of tunics which was so female-biased that it couldn’t possibly have been representative of even a very woman-heavy church? Are we sure that we can make the leap from “Christianity promised women more rights” to “Therefore, women flocked to Christianity?” Wasn’t that the same argument that pundits used last week to predict a blue wave for Kamala? Didn’t white women actually go for Trump, 53-46?

Salzman has one more concern, which is that women had so few rights in ancient Roman society that it’s hard to see how they could have converted at all. When unmarried, they were under the care of their father, who would hardly have let them go out visiting churches full of strange men. When married, they were under the care of their husband, who likewise. A typical Roman man wouldn’t have cared about his wife’s religious opinions, which is maybe why so many of our stories about intermarriages and conversions come from later periods like the Anglo-Saxons.

I don’t know enough about history to referee this dispute, except that say that I think the answer could easily have been different for each of early Romans, late Romans, Hellenized-Jewish-Romans, pagan Romans, upper-class Romans, and lower-class Romans, plus all combinations thereof.

Because Of The Testimony Of The Martyrs

The martyrs are one of the most dramatic parts of the early Christian story. Men and women would endure seemingly-unbearable tortures, continuing to praise God the whole time, sometimes in spite of Roman officials who promised to let them go free if they would just make the tiniest concession to praising Jupiter. These martyrdoms impressed their contemporaries as much as they impress us, and were a major factor driving pagans to Christianity.

Stark is writing in the 1990s, and martyrology c. 1995 does not exactly cover itself in glory. At the time of writing, the most popular theory among scholars (claims Stark) was that the martyrs were masochists. He considers this dumb and offensive theory a natural consequence of historians being reluctant to accept anything that sounds too miraculous or amazing, and there being few other hard-headed rational explanations of the martyrs’ behavior (for some reason, the obvious one - that they believed in God and Heaven - impresses neither Stark’s foils nor himself). He sets out to build an alternative theory: the martyrs were rationally seeking the approval of their community.

Martyrdom not only occurred in public, often before a large audience, but it was often the culmination of a long period of preparation during which those faced with martyrdom were the object of intense, face-to-face adulation. Consider the case of Ignatius of Antioch … Ignatius was condemned to death as a Christian. But instead of being executed in Antioch, he was sent off to Rome in the custody of ten Roman soldiers.

Thus began a long, leisurely journey during which local Christians came out to meet him all along the route, which passed through many of the more important sites of early Christianity in Asia Minor on its way to the West. At each stop Ignatius was allowed to preach to and meet with those who gathered, none of whom was in any apparent danger although their Christian identity was obvious. Moreover, his guards allowed Ignatius to write letters to many Christian congregations in cities bypassed along the way, such as Ephesus and Philadelphia … As William Schoedel remarked,

“It is no doubt as a conquering hero that Ignatius thinks of himself as he looks back on part of his journey and says that the churches who received him dealt with him not as a ‘transient traveller,’ noting that ‘even churches that do not lie on my way according to the flesh went before me city by city.’”

What Ignatius feared was not death in the arena, but that well-meaning Christians might gain him a pardon…He expected to be remembered through the ages, and compares himself to martyrs gone before him, including Paul, “in whose footsteps I wish to be found when I come to meet God.”

It soon was clear to all Christians that extraordinary fame and honor attached to martyrdom. Nothing illustrates this better than the description of the martyrdom of Polycarp, contained in a letter sent by the church in Smyrna to the church in Philomelium. Polycarp was the bishop of Smyrna who was burned alive in about 156. After the execution his bones were retrieved by some of his followers - an act witnessed by Roman officials, who took no action against them. The letter spoke of “his sacred flesh” and described his bones as “being of more value than precious stones and more esteemed than gold.” The letter-writer reported that the Christians in Smyrna would gather at the burial place of Polycarp’s bones every year “to celebrate with great gladness and joy the birthday of his martyrdom.” The letter concluded, “The blessed Polycarp ... to whom be glory, honour, majesty, and a throne eternal, from generation to generation. Amen.” It also included the instruction: “On receiving this, send on the letter to the more distant brethren that they may glorify the Lord who makes choice of his own servants.”

In fact, today we actually know the names of nearly all of the Christian martyrs because their contemporaries took pains that they should be remembered for their very great holiness.

I don’t know, I’m not putting too much effort into writing up this section, because it doesn’t feel like as much of a mystery as some of the others. Maybe all of this was weird in 1996. But since then, we’ve seen plenty of suicide bombers willing to die for their faith. I accept that the Christian martyrs were more impressive - a slow death in the Colosseum takes more grit than the quick detonation of an explosive vest, and dying for peace is more impressive than dying in war - but it hardly seems like as much of a leap.

Honestly, Stark’s “social approval” theory seems only slightly less objectifying than the masochism theory. Some people just have a tendency towards self-sacrifice. I know many effective altruists who, for example, deliberately let themselves be infected with malaria to help speed vaccine research. If someone told them a way that they could help the neediest people in the world by feeding themselves to lions, the lions would no doubt eat well.

Because They Survived The Plagues

However bad you imagine daily life in ancient Rome, it was worse.

Historians estimate that ancient Rome had a population density of 300 people per acre. That’s almost ten times denser than modern New York City, two thousand years before anyone invented the skyscraper3. How did they do it? By cramming people together in unbearable filth and misery:

Most people lived in tiny cubicles in multistoried tenements…”there was only one private house for every 26 blocks of apartments”. Within these tenements, the crowding was extreme - the tenants rarely had more than one room in which “entire families were herded together”. Thus, as Stambaugh tells us, privacy was “a hard thing to find”. Not only were people terribly crowded within these buildings, the streets were so narrow that if people leaned out their window they could chat with someone living across the street without having to raise their voices…

To make matters worse, Greco-Roman tenements lacked both furnaces and fireplaces. Cooking was done over wood or charcoal braziers, which were also the only source of heat; since tenements lacked chimneys, the rooms were always smoky in winter. Because windows could be “closed” only by “hanging cloths or skins blown by rain”, the tenements were sufficiently drafty to prevent frequent asphyxiation. But the drafts increased the danger of rapidly spreading fires, and “dread of fire was an obsession among rich and poor alike.”

Packer4 (1967) doubted that people could actually spend much time in quarters so cramped and squalid. Thus he concluded that the typical residents of Greco-Roman cities spent their lives mainly in public places and that the average “domicile must have served only as a place to sleep and store possessions.”

These tenements had no plumbing. Waste was eliminated by pouring it onto the street, often to the detriment of people walking underneath. Water was brought home from public wells; if you were out, you either walked back to the well or made do. The total public baths capacity of Rome was about 30,000; the total population of Rome was about a million; in practice, the upper classes used the “public” baths and the average citizen had never bathed in their life. Soap had been invented a century or two earlier but was limited to a small pool of early adopters. The cities buzzed with flies, mosquitos, and other insects. It would be eighteen hundred years before anyone invented germ theory.

Tenements were six stories high and frequently collapsed, killing everyone inside. Fires consumed the city on a regular basis, giving rise to colorful legends like Nero fiddling while Rome burnt. Police were limited, and it was understood that you would be robbed immediately if you set foot outside at nighttime.

How did people survive? Mostly they didn’t. Cities were destroyed regularly - multiple times within a single human lifetime! - then rebuilt and replenished with rural population. Stark focuses on Antioch, a Syrian city which was a center of early Christianity. During “six hundred years of intermittent Roman rule”, he finds:

It was conquered 11 times

…and burned to the ground 4 times

…and devastated by riots 6 times

There were 8 earthquakes large enough that “nearly everything was destroyed”.

…and 3 plagues large enough to kill at least a quarter of the population

…and 5 “really serious” famines

…for an average of one catastrophe per fifteen years. The Romans rebuilt the city each time because it was strategically important.

Stark focuses on one of these disasters: plague. The Roman Empire suffered two major plagues during this era: the Antonine Plague of 165 AD and the Cyprian Plague of 251 AD . He theorizes that Christians made it through these plagues much better than pagans, gaining an additional population boost.

Time for some game theory: when a plague comes, you can either defect (flee / self-isolate / hide) or cooperate (altruistically try to help nurse other victims). An individual does better by defecting, but a community does better if all its members cooperate. Stark thinks the pagans defected and the Christians cooperated.

Here is Thucydides’ description of a plague in pagan Athens (admittedly ~500 years before the time we’re studying). People quickly got an instinctive proto-knowledge of how contagion worked, after which:

[People] died with no one to look after them; indeed there were many houses in which all the inhabitants perished through lack of any attention…the bodies of the dying were heaped one on top of the other, and half-dead creatures could be seen staggering about in the streets or flocking around the fountains in their desire for water. The temples in which they took up their quarters were full of the dead bodies of people who had died inside them. For the catastrophe was so overwhelming that men, not knowing what would happen next to them, became indifferent to every rule of religion or law.

Compare the Christian writer Dionysius’s description of a plague afflicting his own community:

Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy, for they were infected by others with the disease, drawing on themselves the sickness of their neighbors and cheerfully accepting their pains. Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead. The best of our brothers lost their lives in this manner, a number of presbyters, deacons, and laymen winning high commendation so that death in this form, the result of great piety and strong faith, seems in every way the equal of martyrdom […]

The heathen behaved in the very opposite way. At the first onset of the disease, they pushed the sufferers away and fled from their dearest, throwing them in the roads before they were dead and treated unburied corpses as dirt, hoping thereby to avert the spread and contagion of the fatal disease.

Could Dionysius be embellishing matters to make his friends look good and his enemies bad? Maybe, but:

There was compelling evidence from pagan sources that this was characteristic Christian behavior. Thus, a century later, the emperor Julian launched a campaign to institute pagan charities in an effort to match the Christians. Julian complained in a letter to the high priest of Galatia in 362 that the pagans needed to equal the virtues of Christians, for recent Christian growth was caused by their “moral character, even if pretended,” and by their “benevolence toward strangers and care for the graves of the dead”. In a letter to another priest, Julian wrote, “I think that when the poor happened to be neglected and overlooked by the priests, the impious Galileans observed this and devoted themselves to benevolence.” And he also wrote, “The impious Galileans support not only their poor, but ours as well, everyone can see that our people lack aid from us.”

Did this matter? It might have! “Modern medical experts believe that conscientious nursing without any medications could cut the mortality rate by 2/3 or even more.”

(if this sounds implausible, keep in mind that “nursing” here includes things like “bringing water from the public well to bedridden people who are too weak to go out and get it themselves”.)

Stark believes that plagues helped the Christians in multiple ways:

The obvious way: 30% of pagans died during the plague, but only 10% of Christians, making Christians proportionally more of the population.

Altering the social graph. Remember, Stark believes that you convert to Christianity after your Christian friends outnumber your pagan friends. If all your pagan friends die, and none of your Christian friends do, this suddenly gets much easier!

Moral testimony: pagans saw their priests and institutions fail the moral test of helping others, while the Christians succeeded.

Even more direct moral testimony: many Christians nursed and helped their pagan neighbors; if you owed your life to the Christians, and all your pagan friends who could judge you were dead, it would be hard not to convert.

Supernatural testimony: if you didn’t understand the game theoretic logic above, then dramatically higher Christian survival rates might seem like God’s favor. Stark additionally speculates that since Christians didn’t flee the disease, they got it much earlier, therefore getting immunity much earlier and allowing them to walk through hospital corridors full of plague victims with apparent miraculous invincibility.

Search for meaning. In some cities, 50% of the population died. The survivors must have been shell-shocked and looking for some sort of meaning behind it all. Paganism had nothing for them - “sorry, we don’t do that kind of thing, would you like to hear another story about Zeus raping a woman and turning her into an animal?” Christians, who had wise words about how God tests the faithful and sometimes brings people to Heaven before their time, must have been a vastly superior alternative.

Putting all these factors together, Stark suggests that the Christian : pagan ratio at the end of a plague could have been almost twice what it was at the beginning.

He doesn’t do a similar analysis for all the other disasters that regularly afflicted a Roman city - the wars, earthquakes, fires, etc - but one can see how the same logic might apply.

Because Jesus Is Lord

Are we allowed to consider this one?

Stark thinks of himself as attacking a scholarly consensus that you’re “not allowed” to consider the content of a religion when speculating about its growth.

This is a little ironic, because to us non-scholars, he himself seems pretty careful not to talk about content, or to talk about it only indirectly. It’s true that the content of Christianity includes opposition to birth control, and rights for women, and helping others during plague. But what about the content content? In his last chapter, Stark relaxes this self-imposed restriction and starts talking about Christ.

Paganism was framed as a business relationship with the gods. You performed the rites and sacrifices, they gave you supernatural aid. You didn’t have to like them any more than you liked your supply chain for any other commodity. They certainly didn’t like you! At its absolute most touchy-feely, paganism might posit a “special relationship” between a god and a city, like Athena and Athens. But even this maxxed out at the sort of relationship between a shopkeeper and a favorite recurring customer who he always remembered to greet by name.

Judaism did better. God has a sort of love-hate relationship with His people Israel, but at least there are clearly strong emotions involved. Still, Stark thinks it was Christianity that really pioneered the idea that God loves individuals. From that, everything else flows. You should love your fellow man (and nurse him during plague). You should love your children (and not commit infanticide or abortion). You should love God back (and be willing to die a martyr for Him). From God’s love flows naturally the promise of Heaven (instead of the shadowy semi-naturally-forming underworlds of the Greek and early Jews). Pagan priests were people who were skilled at the relevant rituals; Christian bishops/priests/deacons were people who loved God especially much. Aside from all the individual ways that Christian love provided an advantage, Stark thinks that paganism just couldn’t compete.

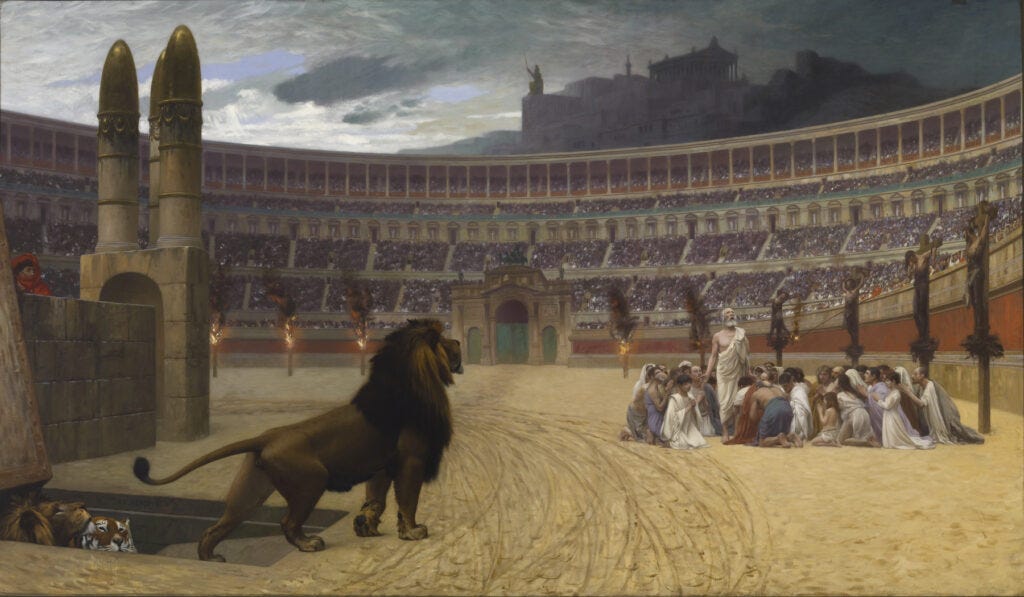

He flirts with the idea that Christianity, in some sense, invented goodness. Here’s the last page of the book:

Perhaps above all else, Christianity brought a new conception of humanity to a world saturated with capricious cruelty and the vicarious love of death. Consider the account of the martyrdom of Perpetua. Here we learn the details of the long ordeal and gruesome death suffered by this tiny band of resolute Christians as they were attacked by wild beasts in front of a delighted crowd assembled in the arena. But we also learn that had the Christians all given in to the demand to sacrifice to the emperor, and thereby been spared, someone else would have been thrown to the animals. After all, these were games held in honor of the birthday of the emperor's young son. And whenever there were games, people had to die. Dozens of them, sometimes hundreds.

Unlike the gladiators, who were often paid volunteers, those thrown to the wild animals were frequently condemned criminals, of whom it might be argued that they had earned their fates. But the issue here is not capital punishment, not even very cruel forms of capital punishment. The issue is spectacle-- or the throngs in the stadia, watching people torn and devoured by beasts or killed in armed combat was the ultimate spectator sport, worthy of a boy's birthday treat. It is difficult to comprehend the emotional life of such people.

In any event, Christians condemned both the cruelties and the spectators. Thou shalt not kill, as Tertullian reminded his readers. And, as they gained ascendancy, Christians prohibited such "games." More important, Christians effectively promulgated a moral vision utterly incompatible with the casual cruelty of pagan custom.

Finally, what Christianity gave to its converts was nothing less than their humanity. In this sense virtue was its own reward.

I appreciate this last chapter, because I’m not sure how much I buy the preceding ones. The first one, about exponential growth, is great, and it clarifies things a lot. But I could take or leave the rest.

The chapter about women doesn’t seem to be true, at least according to Salzman’s research. The one about fertility requires a lot of epicycles about the role of cities. The one about plague can at best explain a 4x increase in the Christian population (out of the overall 60,000x increase that needs explaining). The Jews can at best explain the first five million converts (leaving 35 million more to explain). These are each fascinating windows into the classical world. But they’re such small bites off of the overall mystery that it seems almost pointless to include them: if Christianity could increase 15,000x without the plagues, it hardly seems worth fighting to explain that last 4x increase.

All of this is compounded by the fact that Christianity spread equally gloriously in times and places without any of these factors. The first Christian missionary reached Scandinavia in 710 - by the twelfth century, the whole region was Christian. This is about the same timeline as Rome - but Scandinavian fertility was fine, Scandinavian women already had a decent number of rights, and there were no plagues. What about Germany? Britain? Ireland? Eastern Europe? Russia? Korea? Each of these places had their own idiosyncracies, each benefited from the knowledge that Christianity was already a great religion believed by other regional powers - but each did Christianize, as surely as Rome did. This doesn’t seem predestined. An observer in 600 AD would no more consider it inevitable that Norway would Christianize by 1100 than a modern observer would find it inevitable that Saudi Arabia will Christianize by 2500.

Likewise, the comparison of Christianity’s growth rate to that of Mormonism raises as many questions as it answers. Why is Mormonism so fast-growing? Probably not something something the Jews, or something something plagues. So why do we need to posit that for Christians? Sometimes religions just grow really fast. Why? Probably they’re good religions somehow.

The impression I get from many parts of this book is that the early Christians were closer to morally perfect (from a virtue ethics point of view) than any other historical group I can think of. It can’t be a coincidence that they were also among the most successful. And the few Mormons I’ve met were also exceptionally nice (even though in theory their religion is no more based on love than traditional Christianity).

Stark kind of tries to account for this. He says that religions spread through the social graph, so the friendlier you are, the better you do. But also, you want your religion to be a tight-knit community, and you definitely don’t want your members making so many heathen friends that they deconvert. Different religions find different places along the tradeoff curve. Classic cults (like Scientology) restrict members’ external connections, successfully gaining tight-knit-ness and protecting themselves against deconversion at the cost of curtailing their growth opportunities. Social movements like environmentalism are diffuse enough that everyone knows an environmentalist, but so loose-knit that they’re barely even a movement at all, and environmentalists frequently forget about the cause and go do something else. Somehow early Christianity (and Mormonism) found the exact sweet spot.

Now we can maybe reframe the “virtue and love” advantage. Because Christians were so good, they could interact with pagans without feeling any temptation to leave the faith (Christians were just better to know and have around than pagans). Because they were so kind, they could make friends and social connections quickly. Because they loved one another so deeply, they could have tight-knit communities even in the absence of the normal cultic ban on communicating with outsiders.

Is this all there is? I’m not sure. Also, talk about Jesus is cheap, but I still don’t understand how they managed to be so virtuous and loving, in a way that so few modern Christians (even the ones who really believe in Jesus) are. I’m not making the boring liberal complaint that Christians are hypocritical and evil, although of course many are. I’m making the equally-boring-but-hopefully-less-inflammatory complaint that many Christians are perfectly decent people, upstanding citizens - but don’t really seem like the type who would gladly die in a plague just so they could help nurse their worst enemy. I’m not complaining or blaming Christians for this - almost nobody is that person! I just wonder what the early Christians had which modern Christians have lost.

Maybe it was just selection effects? The kindest 1% of Romans became Christian, whereas later ~100% of people in Western countries were Christian and you had to operate the software on normal neurotypes? But this would imply a very different story of early Christian conversion than Stark gives us!

Or maybe it was persecution effects? Either persecution bled off the least committed X% of Christians, leaving only the hard-core believers behind - or something about proving themselves to a hostile world brought out the best in them?

How come there isn’t a carefully-selected, persecuted group of people today who are morality-maxxing and doing much better than regular society? Is it the Mormons? Seems kind of disappointing, I don’t know, I kind of expected more than that. Is it woke people? I realize this answer will be unpopular, but if you’re a white male than wokeness involves a lot of self-abnegation, which at least rhymes with Christian morality, and they sure did grow quickly. It is effective altruists? I was going to say we weren’t growing fast enough, but 40% per decade is actually a low bar and we probably clear it easily. Maybe all we have to do is keep it up another 260 years!

Or does this particular brand of morality-maxxing necessarily involve God? Stark treats God as a solution to game theory problems; everyone will do better if they cooperate, everyone wants to defect, so tell everyone that God demands cooperation and will punish defectors. Seems fair. But there are billions of people who believe in God today, and it barely seems to help them. There are so many people saying nice things about God and love, and so few morally-perfect early Christians.

The book speculated that the Antonine Plague - the one that killed 33% of Romans in 165 AD - was probably smallpox. A population’s first encounter with smallpox is inevitably horrible - just ask the Native Americans. 165 AD might have been when the disease first evolved, which explains why the Europeans suffered Native American level death rates.

Maybe we should think of early Christianity the same way - when the idea of love first struck a population without antibodies. If so, we may not see its like again.

People sometimes accuse modern social movements like environmentalism, MAGA, wokeness, rationalism, etc of being cults, but AFAIK this rule doesn’t apply to them - most people in these movements get involved by stumbling across the philosophy online and finding that it rings true. It seems to me like these modern movements are more likely to make unique and interesting claims about the world that could attract or repel certain types of people - whereas most cults are pretty similar (this one guy is God, he commands you to chant a bunch and give him money, and here’s a holy book saying we want world peace). I wonder if this should actually be a counter to “cultishness” accusations - “We can’t be a cult, cults always spread through the social graph, but we learned about this movement from a blog!”

Why does this guy have every character from the Cambridge Latin course in his name, one after another? I think the Caecilius of the course is from the same noble family as him, and they either actually reused names across families, or the course authors assumed that they did.

Another source says 200 people per acre, which is “only” 6x denser. These numbers are for New York City as a whole - if we limit ourselves to Manhattan, Rome was only 2-3x as dense.

Note nominative determinism!