Your Review: Project Xanadu - The Internet That Might Have Been

Finalist #12 in the Review Contest

[This is one of the finalists in the 2025 review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

1. The Internet That Would Be

In July 1945, Vannevar Bush was riding high.

As Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, he’d won World War II. His proximity fuse intercepted hundreds of V-1s and destroyed thousands of tanks, carving a path for Allied forces through the French countryside. Back in 1942, he’d advocated to President Roosevelt the merits of Oppenheimer’s atomic bomb. Roosevelt and his congressional allies snuck hundreds of millions in covert funding to the OSRD’s planned projects in Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. Writing directly and secretively to Bush, a one-line memo in June expressed Roosevelt’s total confidence in his Director: “Do you have the money?”

Indeed he did. The warheads it bought would fall on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in mere weeks. The Germans had already given up; Victory in the Pacific was nigh. So Bush was thinking ahead.

In The Atlantic, Bush returned to a pre-war obsession with communication and knowledge-exchange. His essay, “As We May Think,” imagined a new metascientifical endeavor (emphasis mine):

Science has provided the swiftest communication between individuals; it has provided a record of ideas and has enabled man to manipulate and to make extracts from that record so that knowledge evolves and endures throughout the life of a race rather than that of an individual.

There is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear. Yet specialization becomes increasingly necessary for progress, and the effort to bridge between disciplines is correspondingly superficial.

…

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

Bush thought we were ripe for a paradigm shift. Some new method of spreading research, connecting it across fields and domains, and making new discoveries in the in-betweens. The most exciting Next Big Thing of the era was microfilm, and so when Bush let his imagination run a little wild,1 he envisioned a machine enabling us to do grand new things with long books shrunk into tidy rolls:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.

In one end is the stored material. The matter of bulk is well taken care of by improved microfilm. Only a small part of the interior of the memex is devoted to storage, the rest to mechanism. Yet if the user inserted 5000 pages of material a day it would take him hundreds of years to fill the repository, so he can be profligate and enter material freely.

Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion. Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place. Business correspondence takes the same path. And there is provision for direct entry. On the top of the memex is a transparent platen. On this are placed longhand notes, photographs, memoranda, all sorts of things. When one is in place, the depression of a lever causes it to be photographed onto the next blank space in a section of the memex film, dry photography being employed.

Not only could you read and even add to the memex—you could recombine and link works between each other with ease. “This is the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing,” Bush wrote. As a memex user explored his vast library of human thought, he could leave a “trail” of connected articles and photos and his own commentaries. He could connect these trails to one another, split them into fractally expanding branches, save them, and access them over and over again. He could even share his trails with friends, allowing them to insert copies into their own memexes, where they could be expanded and branched and shared again.

I’ll remind you—the year was 1945.

2. First Experiments in Hyper-cyber-space

Bush never did much to make his memex a reality. He was too busy building the National Science Foundation and trying to prevent a nuclear arms race. He had no time to fiddle around with desk-sized personal libraries, fighting Truman’s hawkish hyperfocus on hydrogen warheads.

But Doug Engelbart didn’t have much else to do.

He was a Navy man, a radar technician, just 20 years old when he shipped out of San Francisco. As he tells it, the entire crew were very nervous, seeing as they were being sent off to invade Japan. But just as the ship sailed past the Bay Bridge, “the captain came out on the bridge and looked down on us. ‘Japan just surrendered!’ he shouts. And suddenly all propriety leaves us, and we all say, ‘well then, for Christ’s sake, turn around!’”

Of course, they didn’t, and so Engelbart spent two years faffing around in the Philippines. He lived on a remote island with nothing to do but read and read and read. He spent his first five days camping out by a little stilt hut with a sign reading “Red Cross Library”—and in the Red Cross Library, there was a copy of the September 1945 issue of LIFE magazine in which Vannevar Bush’s description of the memex had been reprinted.

Engelbart claimed that he found the idea “intriguing,” but had lots of radar-technician-ing to do or something, and so it didn’t really resurface for him until 15 years later, when he was writing his Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Engelbart quoted heavily from Bush’s article, and commented:

The associative trails whose establishment and use within the files he describes at some length provide a beautiful example of a new capability in symbol structuring that derives from new artifact-process capability, and that provides new ways to develop and portray concept structures. Any file is a symbol structure whose purpose is to represent a variety of concepts and concept structures in a way that makes them maximally available and useful to the needs of the human's mental-structure development—within the limits imposed by the capability of the artifacts and human for jointly executing processes of symbol-structure manipulation.

After his Framework was published in 1962, under the Stanford Research Institute, Engelbart founded the Augmentation Research Center to make, in essence, some version of the Memex a reality. The ARC received funding from NASA and ARPA, and after six years, Engelbart released his oN-Line System (NLS). It was a revelation.

Engelbart had invented a vast array of tools—including, according to his own Institute:

the mouse

2-dimensional display editing

in-file object addressing, linking

hypermedia

outline processing

flexible view control

multiple windows

cross-file editing

integrated hypermedia email

hypermedia publishing

document version control

shared-screen teleconferencing

computer-aided meetings

formatting directives

context-sensitive help

distributed client-server architecture

uniform command syntax

universal "user interface" front-end module

multi-tool integration

grammar-driven command language interpreter

protocols for virtual terminals

remote procedure call protocols

compilable "Command Meta Language"

Live on stage, in the year 1968, Engelbart started up the NLS, opened a document, and typed some words into it. The words, he said, constituted a statement. And statements made up a file. Engelbart copied, manipulated, saved, and loaded his words and statements and files, zipping around with his newly-invented mouse. He demonstrated his ability to embed documents in one another—images with links to statements, words nested and categorized by one another, files filled with metadata.

And then he paused, and the screen went blank. He explained that he and his colleagues at the ARC had been using this system to do their daily work for the last six months. He mentioned that they had, now, six consoles up and running. He showed the crowd a real document, then navigated to a statement within it. “This presentation is devoted to the AHIRC.”

“What is the AHIRC?” he asked.

Engelbart “froze” the initial statement, clicked on the acronym, and below the words “Augmented-Human-Intellect Research Center” appeared. He kept clicking and freezing, and a trail of nested and related information appeared—a list of funders, a graph of staffing over time, a mission statement. This was hypermedia. These were hyperlinks, he explained. NLS was a hypertext system.

The presentation went on for 90 minutes longer, and became known as The Mother of All Demos.2 At around the 75-minute mark, Engelbart shows that two different NLS users could edit a single document simultaneously. While this was extremely impressive functionality, it was achieved with time-sharing—computation was done on a single machine, switching rapidly between tasks—and became infeasible the very next year, when ARPANET was released and the number of machines you could connect to one system grew rapidly.

Engelbart’s hypertext system was impressive in its own right, even without collaborativity. And still, little came of it—Andy van Dam, an attendee and revolutionary computer scientist himself, would reflect decades later: “Everybody was blown away … and nothing else happened. There was almost no further impact.” Engelbart’s ideas were just a little too out there.

ARC quickly faded into obscurity. In 1972, Engelbart joined an organization called Erhard Seminars Training. EST, or “est” as it was marketed, offered a 60-hour self-improvement course for tech entrepreneurs modeled loosely on Zen Buddhism. Critics suggested that the est course was a mind-control method aimed at raising an authoritarian army. It was quite credibly branded a cult. The founder of est, Werner Erhard, was accused of tax fraud (he fought the claims and won $200,000 from the IRS) and incest (by his daughter, who later recanted).

Engelbart served, for many years, on est’s board of directors.

His researchers all left for greener, less cult-y pastures, and ARC died with hardly a whimper. No one really wanted to associate with Engelbart. His crackpot theories about an internet modeled after the memex fell into disrepute, and, if he was remembered at all, it was for the invention of the mouse. No one cared anymore about the memex, or hypertext.

3. Hyper-dreams of Hyper-everything

Well, one man cared.

Ted Nelson was born in 1937 to two twenty-year-olds, Ralph Nelson and Celeste Holm. His parents divorced in 1939, leaving him to be raised by his grandparents. Both Nelson (the elder) and Holm would go on to extremely-successful film careers: the former became an Emmy-winning director; the latter an Oscar-winning actress. And, at first, Ted seemed to be following in their footsteps.

As a philosophy major at Swarthmore College, he produced a film called The Epiphany of Slocum Furlow, which he described as “a short comedy about loneliness at college and the meaning of life.”3 Nelson also claims to have “[d]irected [and written] book and lyrics for what was apparently the first rock musical” in his junior year at Swarthmore.

Thankfully, his interest in a career as an entertainer soon waned, and Nelson went off to study sociology in grad school—first at the University of Chicago, then at Harvard. Nelson took a computer class at Harvard, in 1960, and “[his] world exploded.”4 He realized the incredible power of computing, quickly intuited that these new machines could be generally applied to everything, and founded Project Xanadu.5

Initially, Xanadu’s scope was pretty limited. Word processors weren’t around yet, but Nelson wanted to build something strikingly similar: he wanted to write a program that could store and display documents, with version histories and edits all stored and displayed at the same time too. Later, Nelson would call this version-history feature “intercomparison.” (Strange coinages will be a… theme; I’m just trying to get you ready.)

Nelson began working on an implementation, but his feature wishlist grew quickly, and he didn’t really know what he was doing, so in 1965, he sought help. He prepared a talk for the Association for Computing Machinery, and dropped, quite frankly, a bomb on the audience:

The kinds of file structures required if we are to use the computer for personal files and as an adjunct to creativity are wholly different in character from those customary in business and scientific data processing. They need to provide the capacity for intricate and idiosyncratic arrangements, total modifiability, undecided alternatives, and thorough internal documentation.

The original idea was to make a file for writers and scientists, much like the personal side of Bush's Memex, that would do the things such people need with the richness they would want. But there are so many possible specific functions that the mind reels. These uses and considerations become so complex that the only answer is a simple and generalized building-block structure, user-oriented and wholly general-purpose.

The resulting file structure is explained and examples of its use are given.

Ted Nelson was building the memex.

Of course, he wasn’t a very technical guy, and so his talk mostly focused on the philosophy of Xanadu, not its implementation. He commented (emphasis mine):

There are three false or inadequate theories of how writing is properly done. The first is that writing is a matter of inspiration. While inspiration is useful, it is rarely enough in itself. “Writing is 10% inspiration, 90% perspiration,” is a common saying. But this leads us to the second false theory, that “writing consists of applying the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair.” Insofar as sitting facilitates work, this view seems reasonable, but it also suggests that what is done while sitting is a matter of comparative indifference; probably not.

The third false theory is that all you really need is a good outline, created on prior consideration, and that if the outline is correctly followed the required text will be produced. For most good writers this theory is quite wrong. Rarely does the original outline predict well what headings and sequence will create the effects desired: the balance of emphasis, sequence of interrelating points, texture of insight, rhythm, etc. We may better call the outlining process inductive: certain interrelations appear to the author in the material itself, some at the outset and some as he works. He can only decide which to emphasize, which to use as unifying ideas and principles, and which to slight or delete, by trying. Outlines in general are spurious, made up after the fact by examining the segmentation of a finished work. If a finished work clearly follows an outline, that outline probably has been hammered out of many inspirations, comparisons and tests.

Between the inspirations, then, and during the sitting, the task of writing is one of rearrangement and reprocessing, and the real outline develops slowly. The original crude or fragmentary texts created at the outset generally undergo many revision processes before they are finished. Intellectually they are pondered, juxtaposed, compared, adapted, transposed, and judged; mechanically they are copied, overwritten with revision markings, rearranged and copied again. This cycle may be repeated many times. The whole grows by trial and error in the processes of arrangement, comparison and retrenchment.

Nelson recognized that the creation of knowledge is cyclical, recursive, self-referential. And he figured that our computer systems should accept and reflect that process:

If a writer is really to be helped by an automated system, it ought to do more than retype and transpose: it should stand by him during the early periods of muddled confusion, when his ideas are scraps, fragments, phrases, and contradictory overall designs. And it must help him through to the final draft with every feasible mechanical aid—making the fragments easy to find, and making easier the tentative sequencing and juxtaposing and comparing.

How do you design such a system? To navigate intuitively within complex file systems, between document versions, and across source materials—to access all the scraps and fragments writers need to write—you would need to establish what Vannevar Bush called “tracks.” You would need to connect and save different ideas, linking them together. That was it—you needed links.

Nelson went further, though—it wouldn’t do to simply have links to all the other files, a writer needed to see the other files before him, needed them to be brought up and displayed alongside his current work on demand. The links needed to contain their targets within themselves—so Nelson called them hyperlinks. And he called text embedded with hyperlinks hypertext, and movies embedded in his structure became hyperfilms, and so on. Nelson wanted us using computers to write and create self-referential, intricately-interconnected (“intertwingled,” as he’d later put it), eminently-accessible hypermedia.

And recall, in 1965, state-of-the-art computing looked like this.

Ted Nelson was thinking far, far ahead.

Maybe too far ahead. Conference attendees were initially excited about his idea, but when he revealed himself to know very little about the technical task of building Xanadu—or even whether it was possible at all—interest evaporated.

4. Failing to Develop Xanadu

But Nelson was all in. He would later write, “This is not a technical issue, but rather moral, aesthetic and conceptual.” Nelson loved knowledge and connection and abstraction—mere technical details wouldn’t stop him from building the best possible computer system for producing and consuming information.

He met Doug Engelbart in the mid 60s, forming a friendship with the only other man taking hypertext seriously at the time, and hopped around unhappily between various academic and scientific appointments. At one point, he and Andy van Dam worked together and produced the Hypertext Editing System—released in 1967, just before Engelbart’s NLS. It was the first computer application to ever have an “undo” button—Nelson claims to this day that he invented it (and the “back” button).

Shortly thereafter, Nelson’s wife left him. In his 2010 autobiography, he writes, “She, reasonably, wanted a Nice Life; women want that sort of thing.” They had a son, whom Nelson continued to visit regularly. “Debbie has been a friend and great support all these years,” Nelson adds. “[S]he believed in me.”

Nelson gave a talk at Union Theological Seminary in 1968 that included this slide, which Nelson considers “the first depiction of what the personal computer turned out to be.”

Around the same time, Nelson claims to have called Vannevar Bush and told him about Project Xanadu. Bush “wanted very much to discuss it with” Nelson, but Nelson “hated him instantly [because] he sounded like a sports coach” and never contacted him again. This, of course, proved to be extremely self-destructive (though I can’t honestly say I would’ve done otherwise).

Because Xanadu was as good as dead. No one would give him the money he needed to work on it, especially not after Doug Engelbart poisoned the idea of hypertext.

Nelson went where there was funding, working briefly on an early word processor called Juggler of Text (JOT). …And then he lost investment, stopped working on the project, and moved to Chicago, where he’d been offered a job teaching at the University of Illinois, to start work on a book. He would call it Computer Lib.

In fact, he started work on another book at the same time, called Dream Machines. By the time he completed each of them, in 1974, ARPANET had been released, and his vision for Project Xanadu had evolved. He published the two works together—Computer Lib was his lamentation over the industry’s disdain for hypertext, and Dream Machines was Xanadu’s manifesto.

Nelson designed and printed the book himself. Its pages mostly look like this:

Self-referential, multimedia, creative, and fun—they were a blueprint for the internet he was building. In the Dream Machines half, Nelson writes, “The real dream is for ‘everything’ to be in the hypertext. Everything you read, you read from the screen (and can always get back to right away; everything you write, you write at the screen (and can cross-link to whatever you read).”

In one section Nelson asks himself, “Can It Be Done?” His answer: “I dunno.”

Remember, Xanadu wouldn’t only involve links between works—it required hyperlinks, which as Nelson understood them, would need to contain the targets in themselves. (Eventually, Nelson would give these embeddings a new name—“transclusions”—and hyperlink came to simply mean “link between hypertext files.”) Every link would run both ways, each hypertext file would know exactly which other files were linked to it and how.

This introduced a few problems, in the new interconnected ARPANET age:

How do you keep track? Where’s the metadata stored? Can you afford enough space for it all?

Who’s keeping track? Nelson was already, allegedly, approached by the CIA over this all—how do you make sure hypertext is a free, democratizing technology that doesn’t spread government propaganda?

What do you do about intellectual property? You don’t want everyone to be able to link everyone else’s work if each link contains the work itself—how do you ensure that people still get paid for their ideas?

Nelson answered (in 1974):

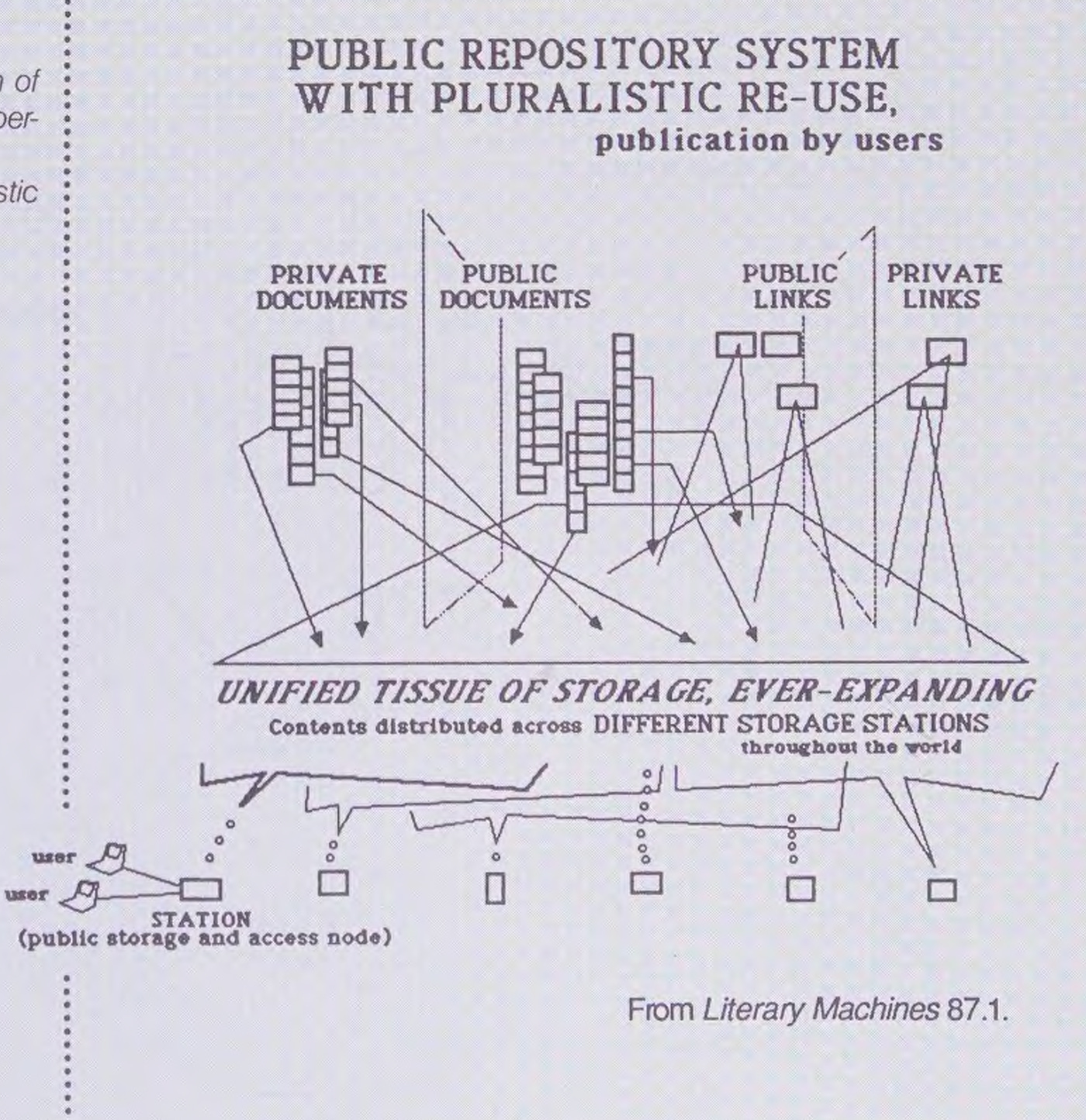

The docuverse keeps track! Xanadu wouldn’t simply be a platform for linkage—it would be the repository for all existing connections between human thought. It would be a universal library.

Storage of the docuverse will be distributed, people can use pseudonyms, and eventually we’ll figure out some good system for authenticating the texts everyone’s linking to.6

Simply put a royalty on the links. If you want to reference a copyrighted New York Times article, then you’ve got to pay the author a little bit. And if someone else links to what you’ve written, then you get a small payout. Presumably, you could build in caveats for short excerpts and fair use kinds of things—“a universal flexible rule [still] has to be worked out.”

He helpfully diagrammed the whole idea, in case it was at all confusing:

A pay-per-click system like Nelson described would first be implemented in 1996.

Computer Lib/Dream Machines became a cult favorite, and Nelson began to gather a small following. In 1979, he moved back to Swarthmore with a group of disciples, and they got to work. The crack team included:7

Roger Gregory, a University of Michigan graduate and Ann Arbor local who’d been corresponding over telephone with Nelson since reading Computer Lib in 1974. Gregory was a whiz with hardware, but suffered from regular bouts of depression, sometimes so strong they would render him “incapable of working.” Gregory paid for the house in Pennsylvania.

Mark Miller, a mathematical wunderkind who’d read Computer Lib and grokked it so hard that Nelson invited him to give a lecture to his UIC class when Miller was just 19, and a sophomore at Yale. The students all thought Nelson was crazy, and so they thought Miller was crazy too. Nelson thought him a genius.

Stuart Greene was a UIC student who thought Nelson and Miller might not be so crazy. He was invited to Pennsylvania too. Nelson, in his autobiography, describes Greene as “the mystic who’d taught holography at 14.”

Roland King, a linguist who, like Nelson, was super into an evangelical Christianity–associated theory of linguistics called “tagmemics.” I can’t make heads or tails of it, but Nelson describes it as a “romantic [extension] of the linguistic ideal.”

Eric Hill, a 15-year-old hacker and indicted felon, who “had been dismissed by the judge with admiration.”

In Swarthmore, Nelson hoped his decades-old dream of Xanadu would finally materialize.

5. Developing Xanadu

Ted Nelson had built Project Xanadu into, for lack of better terminology, a cult.8 He writes:

We all were deeply concerned about the Bad Guys, who we saw as a combination of IBM and the government. (The others were all Libertarians, I still called myself a Cynical Socialist.) The Bad Guys would spy on people, withhold and block information, and give us inferior hypertext. We had to Do It Right, to help prevent this.

This meant using the standard business defenses—especially non-disclosure agreements (I made all of them sign) and secret proprietary algorithms.

The Xanadians had a messiah—Ted Nelson—a gospel—Computer Lib—a persecution complex, a fearful dystopia—“inferior hypertext”—a hopeful utopia—Xanadu—and utter secrecy. Just six dudes in a rented house near Philly, building the internet, hiding from the Feds, signing NDAs, and saving the world.

Nelson spent a summer explaining the project to his team in its entirety. By the end, Gregory, Miller, and Greene were the only ones left. They told Nelson, “We’ll do it,” and moved to another suburb, where they finally began to work on an implementation of Xanadu. The three quickly figured out a new system that would allow users to reference and link to specific parts of a file—they called these links tumblers, and made them work with transfinite numbers. Suddenly, transclusions were really possible.

But after only a few early successes, the team’s progress stalled completely. Greene and Miller were young and left for jobs elsewhere, and so Gregory was left working on Xanadu alone.

Nelson, meanwhile, ran a magazine called Creative Computing for a while, then tried again to build his JOT word processor—this time for the Apple II—then spent a year in San Antonio pitching a watered-down version of Xanadu (rebranded as “Vortext”) to a tech company called Datapoint. Datapoint wasn’t buying, but kept Nelson on in some sort of fake, primitive email job anyway.

Gregory kept working on Xanadu in Philadelphia, slowly running out of money. Ted Nelson held an “Ecstasy party” in San Antonio: “A number of us floated down the river on inner tubes. It was quite lovely.”

In 1987, like he did every year, Roger Gregory went to The Hackers Conference in Saratoga to show off the latest unimpressive version of Xanadu. There, he met a man named John Walker—founder of the wildly successful Autodesk—and pitched the project to him. Incredibly, Walker was interested, and after tense negotiations with Nelson, agreed to fund Xanadu in earnest.

Beginning in 1988, Autodesk poured millions of dollars into the project, and a programming team led by Gregory finally started to make real progress. Walker said of Xanadu: “In 1980, it was the shared goal of a small group of brilliant technologists. By 1989, it will be a product. And by 1995, it will begin to change the world.”

Sweeping rhetoric—clear deadlines.

The team came nowhere close to meeting them. Infighting broke out between two factions—while Gregory simply wanted to patch together his old C code, insisting his product “was within six months of shipping,” the whiz-kid Mark Miller came back from his new job at Xerox PARC, alongside a half-dozen of his closest friends, and insisted on a perfectionistic rewrite in a more flexible language, Smalltalk.

The PARC faction began to drive Gregory up the wall. According to Nelson, it got to the point that he “was throwing things and acting crazy.” So Nelson called John Walker, the two “summoned Roger to meet [them] at John’s house at Muir Beach, and Walker told Roger he was no longer in charge.”

Miller took over and began the rewrite in Smalltalk. Walker’s deadline came and went, and the team delivered nothing. Xanadu’s offices descended into chaos—Miller anointed two PARC programmers to be “co-architects,” and the three of them increasingly left the rest of the team out of the loop. For four years, Miller dawdled about, adding features, giving them clever names (files were “berts,” after Bertrand Russell, and so, for symmetry’s sake, royalty-generating transclusions became “ernies”), and never building them.9

Meanwhile, Ted Nelson was living on a houseboat, attending sex retreats and Keristan orgies, and giving talks in Singapore. He recorded a new soundtrack for his student film, the one from 1959.

In 1992, Autodesk’s stock cratered, and they divested entirely from Xanadu. Miller lamented that his program was just six months from completion.

Ted Nelson started a film studio to make a movie with Doug Engelbart, then left for Japan to get a PhD.

Xanadu’s code was open-sourced in the late 90s.

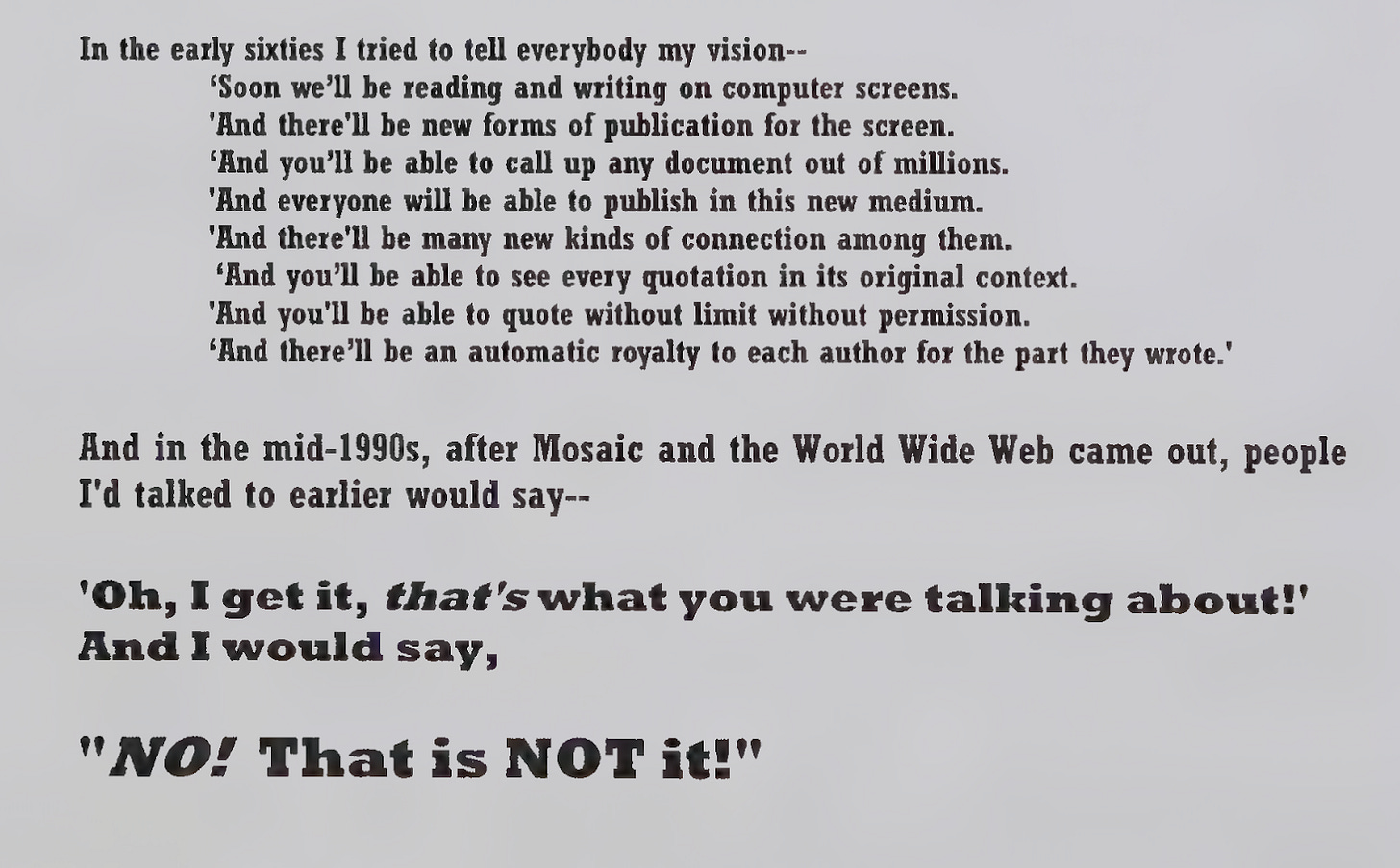

6. The World Wide Web

In March 1989, a British computer scientist named Tim Berners-Lee, working at CERN, wrote a proposal for a system unifying hypertext and the internet. It was ignored.

In 1990, Berners-Lee resubmitted his proposal, it was accepted, and he began to work on the World Wide Web.

The WWW had a number of advantages over Xanadu:

It was much simpler—Ted Nelson wrote of it disparagingly: “Where were annotation and marginal notes? Where was version management? Where was rights management? Where were multi-ended links? Where were third-party links? Where were transclusions? This ‘World Wide Web’ was just a lame text format and a lot of connected directories.” As it turns out, it’s much easier to build a lame text format and a lot of connected directories!

It had institutional buy-in from the start. CERN was huge, it saw promise in the WWW, and it gave Berners-Lee plenty of funding, latitude, and staffing.

Tim Berners-Lee wasn’t a self-important lunatic. He didn’t join cults, nor did he start them. He didn’t attend sex workshops, nor did he intern at them. He was British and proper and serious, and so people took him and his work Britishly, properly, and seriously.

And so, despite Xanadu’s 30-year head start, the Web won the race.

By the occasion of Autodesk’s divestiture from Xanadu, everyone knew Berners-Lee’s creation was the Next Big Thing. It was released publicly in 1993—four years past John Walker’s deadline for Xanadu—and Netscape went public in 1995—Walker’s revolution came right on schedule.

But what kind of revolution was it, exactly?

7. This Is Hell.

Ted Nelson pulls no punches.

Think about the Web we have today. The 2.0 and 3.0 (however you choose to identify it) revolutions included.

What parts of Nelson’s wishlist have we checked off? What are we missing?

Ultimately the Web really is “just a lame text format and a lot of connected directories.” We’re reading and writing, publishing new kinds of media, calling up documents like crazy, democratizing publication to a fault, and… ah. Well, that’s all.

Vannevar Bush wrote, in 1945 (emphasis mine):

Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing. When data of any sort are placed in storage, they are filed alphabetically or numerically, and information is found (when it is) by tracing it down from subclass to subclass. It can be in only one place, unless duplicates are used; one has to have rules as to which path will locate it, and the rules are cumbersome. Having found one item, moreover, one has to emerge from the system and re-enter on a new path.

The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Man cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but he certainly ought to be able to learn from it. In minor ways he may even improve, for his records have relative permanency. The first idea, however, to be drawn from the analogy concerns selection. Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized.

Unlike Doug Engelhart, and unlike Ted Nelson, Tim Berners-Lee never read about Bush’s memex. He built a system that connected people like never before—but made little effort to facilitate the connection of ideas. There are no trails on the World Wide Web—instead, there are misattributed quotes, dead one-way links, constant plagiarism scandals, and widespread misinformation and mutual distrust. It’s often said that we’re living in a ‘post-truth society’. The words we write and videos we share have become entirely unmoored from the ideas underlying them. Strangely, the Web has facilitated more disconnection than was ever possible before.

Ted Nelson, in his own oblique and dodgy way, predicted the failure mode we’re now seeing: “This is not a technical issue, but rather moral, aesthetic and conceptual.” We built our global information-sharing system quickly, efficiently, and technically, when we should’ve treated it as a philosophical and aesthetic puzzle as much as a computational one, and built carefully and precisely.

Tim Berners-Lee took inspiration from the artificial citation and index and reference paradigm of old—he simply scaled up the paper-based system that Vannevar Bush knew was getting out of hand in the 1940s. He gave us a Web shaped like a machine—not a memex shaped like a mind—and then let everyone in the world talk to everyone else on his alien, unwelcoming platform. He built a cold and inhuman Web—so why would we be shocked that the online world became a cold and inhuman one?

8. Whither Xanadu?

It’s extremely hard to like Ted Nelson once you’ve read his autobiography. For instance, in the space of just two pages, he writes about how incredibly virtuous he is for not selling out to Bill Gates, that “friends often tell [him], ‘Oh, you should get a MacArthur Genius Grant!’,” and that Robin Williams once “squatted down beside” him and said: “I think it’s wonderful what you’ve done for the world.”

I don’t think I want to be Ted Nelson’s friend. He very clearly believes that he’s the Internet Messiah.

The only thing that gives me pause is that he might be right.

In 2014, a primitive Xanadu demo was released on the Web. (If you have a Windows machine, another nicer-looking demo exists for you to download.) I mean it when I say “primitive.” This isn’t close to the full product Nelson has been promising since 1965.

But as you play with the demo, scrolling and clicking around, you might just catch a glimpse. It’s all right there. All of the underlying ideas—the scraps and fragments of our nonlinear, recursive thought—traced back to their source. If you squint, almost to the point of closing your eyes, but not quite—you can just make it out. A hypertext system with connection, accountability, verifiability. A mind-shaped system—a real memex.

Maybe it looks a little unnatural, what you see when you squint at Xanadu—what a pain it would be to write in a Xanadu editor, you think. How ugly is that design!

But give the sight a little charity—imagine billions of dollars, maybe trillions, poured into Xanadu. Making it more beautiful, more intuitive. Imagine you’d never seen the Web before—no habits built, no understanding of what a webpage could or should be. What’s so wrong with Xanadu?

Why shouldn’t the internet look (and work) a little more like this?

For that matter, why doesn’t it?

Xanadu had a huge head start. Ted Nelson coined the term “hypertext.” He was doing all of this way before anyone else. He had a mind for design, he was smart, he was charismatic. Why didn’t he become the Steve Jobs of the Web?

I think we can, in large part, trace it back to Doug Engelbart, who, by blind, dumb luck, found himself on a remote Philippine island for two years with nothing to do but hang out in a big hut full of magazines. And there he happened to read Vannevar Bush’s essay, and then, fifteen years later, the thought happened to pop back into his head, and he happened to be a little better positioned, a little better at technology than Ted Nelson, and so he happened to make comprehensive hypertext a highly-visible reality before anyone else.

And then Engelbart joined and helped lead a mind-control cult, and so everyone became very wary of hypertext projects—especially hypertext projects led by cult-y weirdos—and then when Ted Nelson spent decades trying to get anyone interested in Xanadu, anyone at all, they just wouldn’t fund him.

Of course, Nelson deserves plenty of blame too. In many ways, he really was a nutjob, and he certainly wasn’t capable of building Xanadu on his own—still, the concept itself was solid! If Nelson hadn’t turned down Vannevar Bush and Bill Gates and Robin Williams and the half-dozen other famous people he claims were kissing his ass at one point or another, maybe someone sometime could’ve figured out how to build it for him. But he couldn’t do it. Nelson was too busy play-acting as a great, tortured, persecuted genius. By the time he’d become pacified enough to let Autodesk help him build Xanadu, he was too pacified to exercise any sort of authority or discipline over his project anymore. He just went to his sex parties and watched it all burn.

9. Lo and Behold

In 2016, Werner Herzog made a documentary called Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World. In an interview after the film was released, Herzog explained his motivation:

I think we have to abandon this kind of false security that everything is settled now, that we have so much assistance by digital media and robots and artificial intelligence. At the same time, we overlook how vulnerable all this is, and how we are losing the essentials that make us human.

In Lo and Behold, between conversations with TCP/IP inventor Bob Kahn and a baby-faced non-insane Elon Musk, around the 11-minute mark, Herzog visits Ted Nelson on his houseboat.

His narration explains that Nelson has often been called insane. On screen, the near-octogenarian explains, as lucidly and self-importantly as ever: “There are two contradictory slogans: one is that continuing to do the same thing and expecting a different result is the definition of insanity. On the other hand, you say, ‘if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.’ I prefer the latter. Because I don’t want to be remembered as the guy who didn’t.” Herzog replies: “To us, you appear to be the only one around who is clinically sane.”

The two shake hands, and Nelson produces a small camera from his pocket, taking a photo of Herzog and his crew. No doubt, he will file the picture somewhere in his vast, interlinked personal archives, where it will sit and wait, until the day that Xanadu is finally launched, to be uploaded to a true digital memex.

By all accounts, that day is only six months away.

Before getting onto the information-sharing mechanisms of the future, Vannevar Bush did a little imagining about information-recording too: he suggested that Bell Labs’ Vocoder (an early mechanical phoneme-to-text system) could be combined with a stenotype (a human operated, much more extensive, speaking speed–capable phoneme-to-text system) to produce a working speech-to-text machine. Then researchers would have no need to learn typing or to hire a secretary—they could simply speak their findings aloud, and have them automatically entered into the record! It’s interesting to me how this both absolutely came to be—lots of people use very impressively functional speech-to-text systems nowadays—and also largely didn’t—I typed the words you’re reading now with my own non-automated hands. This theme will recur—Bush having very good and important ideas that everyone claims inspiration from, but actually end up mostly perverting or ignoring.

Bush also wrote, presciently-though-not-quite-as-presciently-as-Turing-ly, that “[w]e may some day click off arguments on a machine with the same assurance that we now enter sales on a cash register.” He thought this would be a fairly deterministic process—eventually we’d find some way to encode our semantics perfectly into computer-readable symbols, and then we could use those new computer-readable symbols to construct logical arguments. This isn’t really what today’s arguing-machines do at all, but if you squint enough, it’s not a terribly inaccurate picture.

It’s on Youtube; I think you should watch it. When I was younger, my dad had me watch Steve Jobs’ iPhone presentation; held it up as a prime example of tech and sales, innovation and elegance all rolled up. I liked it at the time. Now, having watched Engelbart’s presentation, I recognize it for what it is: patronizing, mass-market garbage. It’s just nowhere near as cool.

This one’s on Youtube too. I don’t really recommend it. It’s pretty much what you’d expect upon hearing the description “late 1950s experimental student film about being a college student.” In some regard, it’s impressive for what it is, but it’s also very much what it is.

Here, I’m quoting Nelson’s autobiography, published in 2010. It’s called POSSIPLEX: Movies, Intellect, Creative Control, My Computer Life and the Fight for Civilization, and it’s even weirder than the title suggests.

Taking a page out of Jon Bois’ playbook, I’m gonna recommend you stop here for a moment, put on your headphones, turn the volume down to a not-so-misophonic level, and listen to twenty seconds or so of “Doomed Moon” from the 32-second mark, while staring unblinkingly at the words Project Xanadu. Your reading experience will be much enhanced.

In the 1987 edition of Computer Lib/Dream Machines, Nelson writes, “these are now called ‘authentication systems;’ very sophisticated ones exist, and the government is trying to suppress them.” He’s referring to public key cryptography, which wasn’t invented until 1976, and how an NSA official named Joseph A. Meyer had contacted three researchers—named Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman—just before they released a paper in 1977 that introduced a revolutionary new cryptosystem based on the public-key breakthrough.

My description of these men comes both from Nelson’s autobiography and from a classic article in the June 1995 edition of WIRED magazine called “The Curse of Xanadu.” The author, Gary Wolf, takes a somewhat less charitable view of Ted Nelson than I do: he describes Xanadu as “the longest-running vaporware project in the history of computing” and Nelson as “the king of unsuccessful software development.” In my view, the last 30 years of internet history have been extremely kind to Nelson’s legacy, and are reason to disregard much of Wolf’s snottiness in the article. (I do still recommend reading it, though, for a more detailed play-by-play of Xanadu’s history.)

What is it with hypertext pioneers and cults? I wonder if this simply has to do with the fact that these guys were so ahead of their time—the big guys like Tim Berners-Lee didn’t even start thinking about hypertext until 1980. Nelson had, at this point, been at it for 20 years—the kind of person who does that is also the kind of person who writes in his autobiography, “I knew ten times more fifty years ago, when I started in computers, than most people think I know now,” and also absolutely the kind of person who starts a cult.

Well, the team did manage one accomplishment during these years: in 1990, Robin Hanson showed up and ran the first ever corporate prediction market at Xanadu. Its employees assigned a 7% probability to verification of the cold fusion experiment in the next year, and a 70% probability to releasing Xanadu before Deng Xiaoping died. Cold fusion was debunked, and Deng died long before any version of Xanadu would be released. Bonus trivia: this story from Robin Hanson is how I first learned of Xanadu’s existence!