Your Book Review: The Laws of Trading

Finalist #10 in the Book Review Contest

[This is one of the finalists in the 2023 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

A book about trading isn’t ever actually about trading1. It is either:

A former trader sharing stories from their glory days, e.g. Liar’s Poker, the exposé that morphed into a how-to guide, or

Tales of Icarus flying too close to the sun, where readers revel in schadenfreude, e.g., When Genius Failed.

With The Laws of Trading, Agustin Lebron has written something different: part love letter to trading, part philosophical treatise on epistemology and modeling the world around us, and part guide to applied decision-making. Lebron’s Laws are Laws of the Jungle, not Laws of Nature. He views financial markets as the most competitive Darwinian environment on Earth, where participants must adapt or die.

According to Lebron, the book is for people working in finance and trading, as well as anyone in the business of making rational decisions. This explicitly rationalist bent is similar to Julia Galef’s The Scout Mindset or Annie Duke’s Thinking in Bets. Where The Laws of Trading sets itself apart is with the best description of financial market dynamics that I’ve ever seen while diving deep into philosophical concepts.

Why trust Lebron? He is an engineer, worked as a quantitative trader and researcher at Jane Street, and has a deep understanding of trading. He has what Taleb would describe as skin in the game. You and I may read Astral Codex Ten in our spare time, post on LessWrong, and navel gaze about our epistemic certainty, but at the end of the day most of us are pursuing rationality for fun, as a hobby. Traders like Lebron pursue rationality as a profession: Their livelihood depends on having a better model of the world than their competition. There are lessons to learn from them that apply to our daily lives.

1: Motivation

Know why you are doing a trade before you trade.

“What is trading about? Fundamentally, it’s about the relationship between you and the rest of the world.”

Right now, you’re making a trade.

You’re trading your time to read this book review. You have a cost: you could be spending time with your loved ones, exercising, working, sleeping. You might be hoping to learn something, to take away lessons that you can apply to your life, or simply to entertain yourself. Here, off the bat, are two key insights:

We are all making trades, all of the time.

We need a framework for thinking about these trades.

Lebron’s first law states that we must know ourselves and our motivations for trading before we trade. We tell ourselves many stories, but someone with intellectual honesty – the person with the most alignment between their motivations and actions – will take money from the person who didn’t go through the work to understand their own motivations.

There is a reason that Citadel and other hedge funds pay millions of dollars to trade with retail. They know why they are trading: to maximize profit. And the dilettante who “trades for fun” will be eaten alive by a firm with a much better model of a) the world and b) the dilettante themself.

Why did I write this book review? To test my intellectual mettle. I could easily have posted this book review elsewhere, but no, I wanted to see how I stack up against other ACX Book Review contest participants.

Similarly, this is often the reason people get into trading. One motivation that Lebron explicitly calls out is intellectual validation. You can toil in obscurity for years as an academic. But in trading, there is a quick feedback loop. If your P&L showed $10M last year and the guy sitting next to you showed $8M, you have demonstrated who is “cleverer” and established a clear hierarchy.

What lessons here transfer to our daily lives? Like Paul Graham, Lebron encourages us to keep our identities small. He gives the standard decision-making advice to write down your framework and reasoning for why you made a decision at a specific point in time, in order to avoid biases after the fact.

This section of the book contained good general advice, but nothing that will be particularly new for the median ACX reader.

2: Adverse Selection

You’re never happy with the amount you traded.

Now we start to get into the good stuff. Financial markets are an information aggregation mechanism, relying on multiple parties’ beliefs and recursive Bayesian updates of an individual actor’s beliefs based on the beliefs of others2.

Market mechanics demonstrate Bayesian beliefs in action. The following quote is quite long, so skip over it if you don’t want to dive deep into the psychology of making a market. I retained it in full because this is quite literally the best description I’ve ever seen of the Bayesian dance between two market makers:

“You are a market maker in South African mining companies. Through years of effort and continual improvement, you have built a trading model for the company Veldt Resources. You walk into work one day, ready to set up your trading for the day. It's a stock that doesn't trade much, and usually there are only two market makers: you and another (we'll call her Jo). She's sharp, and she competes well to trade against customer orders that come in.

Your model has Veldt valued at 54.35 ZAR (South African rand). You're going to start quoting the stock, so you're about to turn on your machine making a market 54.25 - 54.45 (1000x)3. Before you turn on, you check the current market and notice that Jo has already turned on and she's making her market 53.50 - 54.00 (2000x). If you were to turn on your machine, your market would cross her market, and you would buy 1000 shares from her for 54.00.

You now need to make a decision. Whose model do you believe more, yours or Jo's? If you believe yours, you should turn on your machine, trade at 54.00, and expect to make money. If you believe Jo's model, you should adjust your own model parameters to match her market and turn on, making a similar market to hers.

What to do? As with many dichotomies, this is a false one. And as with many decision processes, Bayesian reasoning lights the way…

…Jo presumably believes Veldt is worth around 53.75 (the average of her bid and offer). But how confident is she in her belief? The width of her market can give you a clue. It's 0.50 ZAR, whereas yours was going to be 0.20 ZAR wide. All other things equal, you should think that Jo only has 40% (0.20/0.50) of the confidence in her fair value as you do in yours.

On some absolute scale of confidence, you can say you had a belief-strength of 100 in your fair value of 54.35 (before seeing Jo's market), and Jo has a belief-strength of 40 in her fair value of 53.75 (before seeing yours). And it turns out the weighted average of these two beliefs is quite a reasonable way to combine them: 100/140 * 54.35 + 40/140 * 53.75 = 54.18. Your updated fair value, having seen Jo's market, is thus 54.18 ZAR.

This procedure is a quick, heuristic, and reduced version of Bayesian belief-updating, and a good reference on the subject is A.L. Barker's 1995 paper.

After updating, you now believe that the stock is worth 54.18. Assuming your trading costs, risk limits, and return requirements are satisfied, buying 1000 shares for 54.00 is a good trade. Naively, you might just put out a 54.00 bid for 1000 shares, trade with half the 2000 share offer, and hope to collect your expected-value ZAR.

In practice, however, you might be able to make even more. If Jo is making a 0.50 wide market, maybe she'd be willing to sell lower than 54.00. It's conceivable that if you put out a 53.90 bid for 1000 shares, Jo will sell at that price, and you collect an extra 100 ZAR!

Of course, Jo could react differently. She could see your bid and use that information to change her market, in much the same way you did before turning on. These are difficult decisions, ones where experience with the product and the market make a big difference in being able to eke out a little extra edge. Let's play it safe however and pay 54.00 for 1000 shares.

You trade, and Jo reacts by immediately canceling her market. This is not an uncommon occurrence in illiquid stocks, especially in emerging markets, so you're not too surprised. You wait a couple of minutes, mentally visualizing Jo in front of her six monitors, evaluating her trade and her model.

Finally, she turns back on. Her new market is 53.50 - 54.05 (10000x)! You reason that Jo has seen that someone (you) disagrees with her valuation of the stock. Jo is a good Bayesian like you, and so she has incorporated that information into her model and updated her beliefs about the fair value of the stock. Her updated belief is that she now wants to sell even more stock, at a marginally higher price. Clearly, she almost entirely discounts the information you've communicated to her with your trade.

How should you react? It seems fairly clear that, assuming Jo is not a crazy or incompetent market maker (usually a fair assumption), your trade was a bad one. You bought 1000 shares, when in retrospect, you would have wanted to buy much less, probably zero.

Imagine instead that Jo had turned back on with a market of 54.00 - 54.50 (1000x). Her reaction now clearly indicates the information you gave her with your trade is valuable, and she has adjusted her beliefs accordingly. Your trade was probably a good one. Don't you wish you had bought all 2000 shares on offer?

No matter what Jo's reaction is, you will be unhappy with your trade. Note that Jo will be unhappy too, since retrospectively she should have either made her initial market bigger or smaller. Welcome to the joyous world of trading!”

Whether or not you make money, you have regrets! If you profited, you could have made more. If you lost money, you shouldn’t have made the trade at all. Like death and taxes, you can’t avoid adverse selection.

Lebron continues to highlight a few areas of trading that have adverse selection problems.

First, IPOs. If you buy the stock in an IPO, you expect the share price to “pop” on the first day of trading. However, if others also have this expectation, the round will be oversubscribed. You can only get the quantity of shares that you bid for when the market doesn’t think the shares will go up. So if you are able to get the shares that you want, the IPO is likely a dud. See also: Venture Capital fundraising.

Second, powerful entities that change the rules of the game while you’re playing. Exchanges nullify “erroneous” trades. Brokerages limit buying. Anyone who tried to buy GameStop stock on Robinhood on January 28, 2021, knows this form of adverse selection all too well.

Lebron also highlights “special trades”, in which you should throw the “normal rules” out of the window. This advice generalizes to other areas of life:

“The normal rules do not apply. If you remove yourself from our usual routine, if you think hard and clearly about the specific situation, maybe you can do something good. Perhaps even great. Others will be paralyzed by inaction, but perhaps you won’t be. Crises can be opportunities.”

3: Risk

Take only the risks you’re being paid to take. Hedge the others.

In trading, as in life, you can make the right call in expected value terms but still lose due to randomness. Some of that randomness is avoidable. Some of it is not — and can be accounted for by hedging. Here, Lebron encourages us to rely on multiple risk measures and actively seek to understand the risks that we might be subject to.

That’s all well and good in the world of finance, with derivatives contracts. But how might this apply in other areas of life?

If you work for a publicly traded company and are compensated in stock, sell your shares as soon as you receive them. This is not because I don’t expect the share price of Microsoft/Meta/Apple/etc. to go up. The stock may very well outperform the market. But you are not being compensated for the added risk that you take on here. Your employment prospects at Microsoft/Meta/Apple/etc. are highly correlated with the share price. When the share price is down is when layoffs happen. Former Enron employees can chime in here.

Similarly, it makes sense to hedge anything that is outside of your control. Let’s say you’ve decided the crypto bear market of 2023 is a great time to start a new crypto company. Your success depends on things within your control, such as:

Your idea

Your hard work and ability to execute

Your network for hiring

Your ability to fundraise

Etc.

As well as some things outside of your control, such as:

Interest rates

The current VC fundraising environment

The performance of crypto as a sector

The performance of tech overall

Etc.

It might make sense to short the overall tech sector or a basket of publicly traded crypto-related companies so that your trade of time and foregone income to start your new crypto company is associated with only the risks you can control.

But some risks you can’t hedge. These are the more interesting ones. There is counterparty risk (your trading partner blows up), liquidity risk (the market you used to hedge dries up), or even political risk:

“Living in the developed world, it’s easy to fall into the seductive assumption that the rule of law applies strongly everywhere. This is far from the case. A foreigner trading in an emerging market is frequently among the first “victims” of any political turmoil.”

Lebron is meticulous in the ways that he thinks about risk. He highlights that in the markets, you need to be exceedingly paranoid to survive:

“Certainly, the modern compendium of mental illnesses (DSM-5) takes a dim view of people who think everyone is out to get them. Yet financial markets are different: people really are out to get you, after all.”

I don’t think enough people consider risk and the hedges you can take in the context of a career. I’ve spent the past several years working at startups, where I’ve placed a hugely levered career bet. I’m trading my time and the opportunity cost of another job to work at my current employer. My salary, stock options, expertise, and social capital that I build from working 10 hours per day is fundamentally long (and has risks associated with):

The tech industry

My startup’s industry

My individual startup

Our customers’ business viability

“Many trades that look different on the surface can in fact be the same trade in disguise, and trades whose edge appears to derive from one risk are actually bets on another risk.”

It might make sense to hedge some of that risk – simply having friends that work at other companies and in other industries so that all of my social capital isn’t in one basket is a start4.

My only gripe here is that I would have liked to see Lebron call out ergodicity more explicitly. Blowing up your account might be fine as a trader – if you have a decent prior track record, you can probably just get a job at a different firm – but in life other losses are less reversible. As far as we know, this is the only universe we have access to. It doesn’t matter if your bet was positive EV and you won in 51% or 75% or even 99% of universes. You should place a high premium on staying alive and having enough bankroll to play the next round of the game. This is more important outside of finance than in the world of trading.

4: Liquidity

Put on a risk using the most liquid instrument for that risk.

Liquidity isn’t something I think about in daily life. But I probably should. A personal example: I gave up the liquidity of a month-to-month gym contract in New York City in February 2020. I paid one year upfront for a 10% discount. Oops.

Lebron also reminds us that the 30-Year Mortgage is an Intrinsically Toxic Product, a concept that will resonate with all of the Georgists here.

“The usual path to homeownership exposes people to a financial decision that would, it seems clear, be ridiculed if it were taken by any self-respecting public company.”

Among other issues:

“The home is bought and sold through an opaque cartel of brokers whose interests are demonstrably not aligned with those of their customers”

“The ability to service the debt (the mortgage) is highly correlated with local economic conditions. This means that if you lose your job and need to sell your house, you will typically find it an exceedingly bad time to try to sell your house.”

“Residential real estate has historically returned significantly below equity markets over long time horizons”

But I’m not so sure that these lessons are directly applicable to other areas of life. Some of the best things in life come from lashing yourself to the mast, burning the boats behind you, willingly giving up liquidity. The deepest monogamous relationships are built from an irrational investment in one other person, saying “In sickness and in health, until death do us part.” How many scientific problems were solved because one person had an irrational willingness to: Just. Keep. Going.

Sometimes it’s powerful to use the sunk cost fallacy to your advantage. Investing in relationships, subject matter expertise, even putting down roots via *gulp* homeownership reduces your liquidity, but also leads to some of the best (if intangible) things in life.

5: Edge

If you can’t explain your edge in five minutes, you don’t have a very good one.

OR

The long-term profitability of an edge is inversely proportional to how long it takes to explain it.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis is one of the core concepts taught in Finance 101. The Efficient Market Hypothesis is a lie. The person that better understands the nature of a small sliver of the world (e.g. Apple’s share price) will make more money than others.

Modern financial markets are exceedingly competitive. This means that the bigger you think your edge is, the more likely it is that you’re wrong.

“Evolutionary thinking applies quite directly when thinking about the evolution of markets. Having an edge in a mature market means understanding the world better than other traders, even ones who are already highly skilled. In fact, the marginal trader in modern financial markets is quite sophisticated and skilled indeed.”

Lebron here warns us of getting too cute with data, of changing variables. Enough randomness will produce an “edge” that is likely to break down the second a trading strategy hits the real world. You can always find a statistical correlation if you change enough variables. But this is fundamentally the same problem facing the replication crisis in social sciences.

Lebron argues that we need stories here. Edge is expressed in stories: an edge does not exist without a clear mental representation of that edge. Pure linear algebra does not suffice.

I’m not so sure. It seems like AI companies are pushing forward technology in a way that suggests that mental representations are not the only path to intelligence. Lebron discounts “black box” trading strategies without much discussion of their potential merits. Are all of RenTech’s models explainable by a story? The firm is notoriously secretive, so I don’t know, but I’d guess not.

“Frequently a good trade appears, has a seemingly insurmountable difficulty, and it is mere persistence that knocks down the final barrier. There may have been many others who looked at the idea, wanted to do it, but couldn’t get past that last hurdle.”

Before Sam Bankman-Fried was the face of Why Effective Altruism is Bad, before he even founded FTX, he made money arbitraging the difference between Bitcoin prices on Japanese and American exchanges. I’m reminded of that trade here. It isn’t a particularly elegant trade, it doesn’t require deep technical knowledge or any models. It was a schlep. It was all operational work: figuring out how to open a Japanese bank account, transferring money between the US and Japan, standing in line for hours every day at both US and Japanese banks (presumably this wasn’t the same person).

In as technical a field as trading, sheer willpower is often what gets things done in the end.

6: Models

The model expresses the edge.

Lebron drills into us that a model is the tool for expressing an edge. The model is not the edge. The model does not give us unique knowledge about the world. The map is not the territory.

He dives into the difference between generative (G) and phenomenological (P) models. G models express a worldview and fit data into that way of thinking, whereas P models solely look at the empirical data to build a worldview.

Models of the world differ from models of markets, though. Markets have quick feedback loops, are explicit in terms of what they measure, and are easy to quantify at a specific point in time. Most of our models for the world, though, are ill-defined and explicit.

Models are only as good as our assumptions. As an aside, this is a common criticism of rationality or Effective Altruism – you can justify any worldview if you assign your model input weights in just the right way5. I also tend to think that “traditional” EA is overly dependent on P models, and doesn’t embrace the G models that led to economic reforms in India in the 1990s or the economic policies that led to rapid economic development in Southeast Asia in the second half of the 20th Century. Interestingly, I think a lot of longtermist EA, specifically AI alignment, leans the other way, relying on G models which explicitly assume a certain P(doom) and work backwards from there. (Though I won’t pretend to be an expert here or to understand everything, so take this with a grain of salt.)

Overall, startups and tech seem to take heed to Lebron’s lesson much better than the folks hanging out on this part of the internet: “Even if a model makes good predictions about some future value or event, that knowledge is useless without also knowing how to take advantage of that prediction.”

Now we get a bit philosophical. By acting, you change the nature of the market. Your model predicts things that might not be true as soon as you start trading (and changing the environment) based on it.

When you’re right, everyone else sees the same trades that your model does and will beat you to them. When your model is wrong, others don’t act, meaning adverse selection rears its ugly head once again. So your model shows you with an edge, but in practice you only make the trades where you don’t have an edge.

Lebron closes by arguing that G models are best for understanding other people, and are good in and of themselves:

“You can also see connections to traditional moral philosophy in thinking about modeling the behavior of others. To have a good G model about someone else is to have some measure of empathy and compassion for that person: what they’re like, what they think and feel, putting yourself in their shoes. Pragmatically, developing the skill of empathy and compassion for others is, aside from a moral good in itself, an excellent way to understand better the people who surround you. More people working to develop good G models of others is surely a small step to a better world.”

7: Costs and Capacity

If you think your costs are negligible relative to your edge, you’re wrong about at least one of them.

This section of the book displayed a good amount of epistemic humility, words that I didn’t expect to be typing in the context of a book about trading.

Lebron tells us that trades don’t exist independently in the universe — in the n-dimensional space of all possible trades seeking to optimize profitability, if you have a gigantic mountain of profitability, someone else has probably at least discovered the base. So you probably don’t have a profitable trade; rather, you are misunderstanding something about your trade. You’ve either overestimated profitability or underestimated cost.

Lebron highlights four types of trading costs:

[graph that didn’t show up correctly here: two axes and four quadrants, with the axes being visible ←→ invisible costs and linear ←→ nonlinear costs]

Here, we’ll focus on Quadrant 4, where he highlights a few interesting phenomena.

Herding. It’s likely that if you have a profitable trading strategy, either:

Other firms discovered a similar strategy independently and/or

You’ve “stolen” the idea from someone else (say if you leave a firm), or vice versa

Lebron highlights Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) as an example here, which suffered a famous blowup in 1998. This hedge fund is often discussed in the context of betting on Russia just before it defaulted on its debt, but an under-discussed aspect is the market mechanics. Other firms were copying LTCM’s trades, so there was a liquidity issue and a cascade of failures when the firm’s margin positions needed to be unwound.

Lebron also discusses opportunity cost, a concept with which most will be familiar. But here, he discusses the cost in the context of trading. Ultimately, this is an explore/exploit problem. How should a trading firm weigh maximizing profit for today’s strategies, as opposed to working on organizational efficiencies so that you can have the capacity to work on tomorrow’s strategies?

There is a clear career parallel here: I’ve seen so many people get locked into their current role due to inertia, whereas the ones who succeed long-term appear to prioritize their own learning and exploration.

As a case study, Lebron discusses how Bell Labs (AT&T) maintained a position of dominance for half a century. He attributes this to four things:

First, they hired the best. There was interaction between three groups that did not interact at most organizations.

Scientists and engineers who conducted exploratory research.

More applied engineers, who took the work of the first group and integrated their discoveries into existing problems at AT&T.

A third group of engineers who put the work from the first two groups into production.

This seems to have been cargo-culted at most modern tech companies. Ping-pong tables and nap pods don’t replace a true culture of cross-pollination of ideas in a boring cafeteria.

I’m reminded of the story of Richard Feynman in academia6. His colleagues who kept their office doors closed made progress on their research in the short-term, but hit stumbling blocks. Those who kept their doors open didn’t seem to make much progress initially, but eventually outpaced the “closed door” scientists. They had new ideas and research directions based on all the interesting conversations they were having with others.

The simple lesson here is to get outside of your bubble a bit more. Maybe the normies have something valuable to say once in a while.

Second, an emphasis on continuing education. This blew me away: Bell Labs developed a syllabus of graduate-level courses and taught it to any interested employee. They didn’t outsource the curriculum or the teaching.

Third, a technical staff that was held in just as high of an esteem as the PhDs who managed them. This seems to be why there is little innovation in government: talented engineers are treated as second-class citizens in research labs, so they work for Stripe and OpenAI instead. Similarly, one can attribute the lack of innovation in hospitals to doctors holding all of the institutional power. Often, all a hospital needs to save lives is simple practices that other businesses figured out long ago, but the hubris of MDs prevents this from happening. But I digress.

Fourth, a culture that embraced failure. While many companies say they have a culture of “failing fast”, how many actually mean it?

Some of the best parts of this book are the diversions. This book is in a sense nostalgic – edges are lost over time, trading firms come and go, entire markets disappear. All you have along the way is the knowledge that for one instant, in one market, you had knowledge that the rest of the world didn’t and used it to make one profitable trade.

8: Possibility

Just because something has never happened doesn’t mean it can’t.

Corollary: Enough people relying on something being true makes it false.

“Impossible” and “25-standard deviation” events sure seem to happen awfully often in the financial industry.

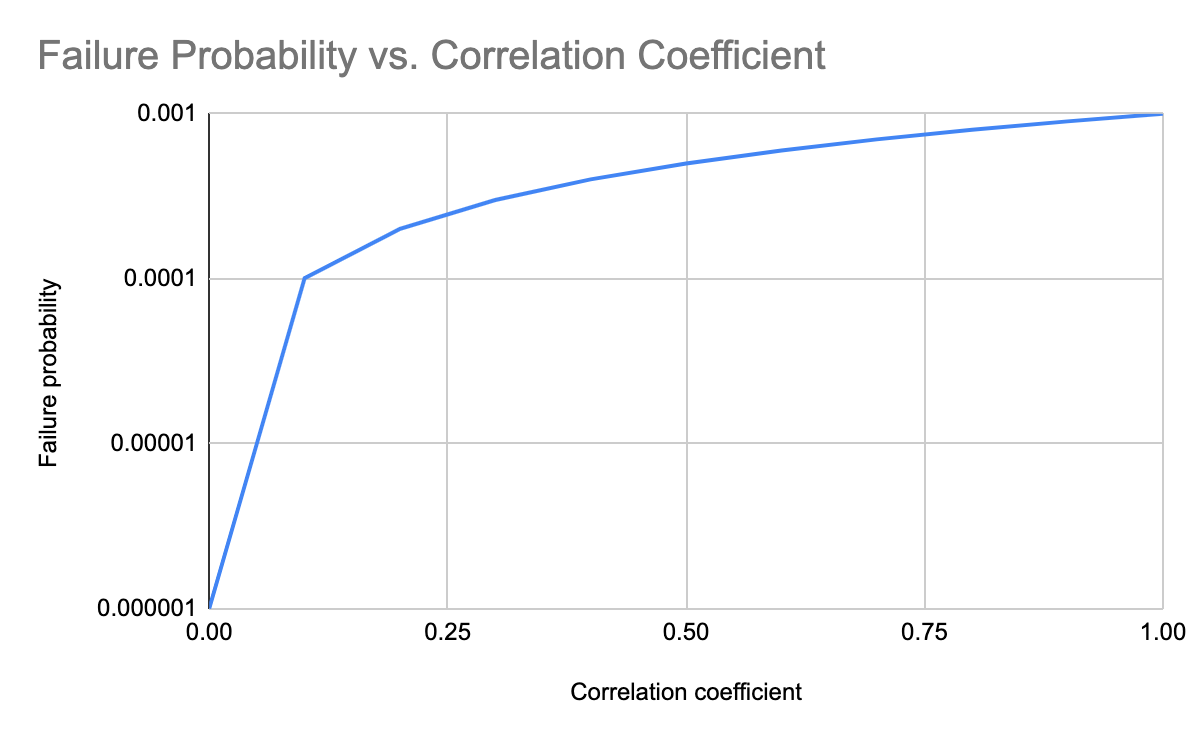

Consider an airplane engine that has a 1/1,000 chance of failing. Each plane has two engines, so that if one fails the other can still operate and get everyone to the ground safely. That’s great if the engines act as completely independent variables, but what if failures are correlated?

The key insight here is that small correlations create large changes in failure probabilities. Namely, a relatively “small” correlation of 0.1 increases the probability of engine failure 100x.

The feedback loop of markets is great at hiding these correlations until something goes wrong. When it does, you have highly-correlated mortgage-backed securities kicking off the 2008 Financial Crisis.

One of Lebron’s more interesting insights is that markets are stochastic, self-organized feedback systems, which means that both momentum trades (a price that is going up will continue to go up) and mean-reversion trades (the exact opposite) are valuable at different points in time.

I found this to be a good framework for thinking about AI. Some folks are clearly betting on momentum – that GPT-X products will continue to improve, reaching AGI (if it hasn’t already). The other side of the coin is bets on mean-reversion, which focus on the S-curves of technology and take a historical view. I’m old enough to remember that in 2016 everyone was talking about how self-driving cars would mean the end of truckers, and there’s more demand than ever for them today.

9: Alignment

Working to align everyone’s interests is time well spent.

This is the principal-agent problem. Whenever the person investing the money is not also providing the capital, you’re going to have problems.

Follow the incentives. When a fund manager is paid 2% of assets under management (AUM), the incentive is to raise as much money as possible. When they are paid 20% of profits, they’re incentivized to make high-risk investments, as their upside is uncapped but their downside is capped at $0.

High-water mark provisions help with this. Basically if your fund had $1 billion AUM last year and you lost 30% this year, you now have $700 million. As the fund manager, you don’t get paid until you’re back to the $1 billion mark.

But…then you just shut down your fund, return the $700 million, and start a new fund.

Lebron argues that the only way to resolve this problem is to perfectly align capital and labor.

I wonder how much of the Renaissance Medallion fund’s success comes from a) this perfect alignment of incentives vs. b) capital limits, meaning that strategies can be executed that would not work at a larger scale.

Lebron argues that everyone acting as an owner is a good thing. And I tend to agree! But there’s a free-rider problem here that he doesn’t address. I’m writing this book review instead of working at my day job as a tech employee. I’m an owner — but my salary and equity was negotiated a few years ago when I signed my job offer. If I were a salesperson working on commission, perhaps I’d be singing a different tune. Aligning incentives is easier when you’re working at a job where performance is a) easily measurable and b) a direct output of your labor (say, as the Portfolio Manager at a hedge fund).

Lebron also argues that, within an organization, consistency of culture is more important than the specific culture. I fully agree – this is particularly egregious at tech companies. Many claim to support work-life balance but then ask you to work weekends, or say “we’re a family” but then lay off employees the second they have trouble raising the next round of funding. Employees can see right through this. Put your flag in the ground and say what you actually stand for. If you stand for everything, you stand for nothing.

10: Technology

If you don’t master technology and data, you’re losing to someone who does.

This point is self-explanatory and I don’t think it needs further exploration for the average Astral Codex Ten reader.

Will machines take over the world? Lebron straddles the line here and states in the context of trading, a human-machine hybrid still does the best work, given our complementary skill sets. Humans have higher-level thinking and understanding context, whereas computers possess the speed and iteration ability necessary to implement models. This book was released in 2019 — I’d love to see if Lebron has updated his priors at all based on recent developments in AI.

There’s also an interesting diversion here into software development. Specifically, Lebron tries to quantify technical debt, which I haven’t seen done before.

11: Adaptation

If you’re not getting better, you’re getting worse.

The markets are a very scary place, and you are in an existential arms race with your competitors. Adapt or die. At the individual level, group (trading desk/business unit) level, firm level, and market level. Adapt or die.

That may seem harsh. But no – Lebron praises trading as a positive-sum game. International financial markets allow the flow of capital from rich to poor countries, giving rich investors a return and raising the standard of living in the developing world.

This is a striking perspective to have on trading. I’ve heard traders describe the work they do as “net neutral” and “adding no value to the world”. Conversely, Lebron views trading as an act of creativity, a way to make the world, in one small way, a better place through creating efficiencies in markets. His philosophical approach to markets is best demonstrated through this story of a trader named Mark,

“Tomorrow will be more difficult than today, and the day after more difficult still, and on until the day he decides to retire from the business. There is no respite and there are no pauses to the inexorable adaptation of markets.

It’s easy to view Mark’s job as a soul-destroying, almost Sisyphean effort. And indeed, it’s this ceaseless competition that does, over time, break the will of many market participants. But I will argue in what follows that the best traders view their situation with very much the opposite perspective: as a liberating and redemptive force…

…Profitable traders are some of the most intelligent, driven, perceptive, and adaptable people on earth. To relegate such a person to a life of maintenance and literally trading on past glories sounds and is soul-destroying. The essence of trading, the thing that makes it such an interesting and stimulating undertaking, is this very process of adaptation and competition.”

One can imagine Lebron, in a previous life, penning the words “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Beyond the philosophy, while reading this book I was struck by the fact that trading is one of the few true apprenticeship systems that remains for white-collar work. You can career switch into the technology industry without a degree. There is a clear educational path to becoming a doctor or a lawyer. But trading is a bunch of dudes (and it’s almost always men) behind closed doors working on intellectually challenging problems. Lebron recognizes this as well:

“Autodidacts in trading are like jailhouse lawyers: for every person who’s truly discovered and developed a successful strategy sui generis, there is an army of people who either significantly undervalued the teaching that others provided, or they are deluding themselves about the profitability of their trading.”

The Laws of Trading opens the door to this world a crack and allows the rest of us to peek in, ever so slightly.

The book actively used by traders is perhaps the driest thing that Nassim Taleb has ever written: Dynamic Hedging: Managing Vanilla and Exotic Options.

Like any good Bayesian, he introduces us to Bayesian statistics and its merits over Frequentism, then points us to the work of Eliezer Yudkowsky to learn more.

You’re offering to buy 1,000 shares at 54.25 and to sell 1,000 shares at 54.45.

As an aside, this seems to sometimes be a failure mode for Rationalists and EAs. They hang out in the same circles, leading to correlated career paths, social networks, and groupthink.

This is also the entire field of Investment Banking: build a model, then massage the inputs to get the multiple that the Managing Director tells you to.

No luck finding this story via Google or ChatGPT, but I think I’m getting the details broadly correct.