Your Book Review: The Family That Couldn’t Sleep

Finalist #4 in the Book Review Contest

[This is one of the finalists in the 2024 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

“You wake up screaming, frightened by memories,

You’re plagued by nightmares, do we haunt all of your dreams?”

The Family That Couldn’t Sleep by D. T. Max was published in late 2006. This glues it to a very particular era. A spectre was haunting Europe – the spectre of mad cow disease. Something was tearing through Britain’s cows, turning them inside out, eating their brains and thrashing their souls. It had been doing so since, DTM thinks, “the late 1970s”. When we look back in retrospect and think about a timeline like this, knowing everything we know, you can’t help but feel a shiver down your spine.

By 2006, some few hundred people had developed variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, colloquially “mad cow disease”. They were almost all young adults in the United Kingdom. The disease was a nightmare – healthy young people succumbing to a terrifying dementia, caused by naught but a beef dinner they had enjoyed years ago. Few diseases were more horrific. Even the worst neurodegenerative disorders rarely struck people so young. The fact it was caused by – and covered up by – the cattle industry made it all the worse.

The numbers were down by this point; the fear of a mad cow pandemic seemed to flicker, then die. The dust was settling, as it were, and it was just now possible to write a history. Simultaneously, it was still in the spotlight. Prion diseases gripped people’s souls with fear. You couldn’t sell a book about mad cow so well ten years later; people were much less scared of it. “That thing people were panicking about in 1999? Wasn’t it a nothingburger?”

(forgive me for “nothingburger”)

The Family That Couldn’t Sleep comes from this era of...optimism? Yeah, let’s say optimism. The wildest predictions – that hundreds of thousands of people across Britain would be struck by vCJD around the turn of the millennium – were clearly wrong. The disease was severe enough to strike the fear of prion diseases into people’s hearts; the name, entirely unfamiliar a few years earlier, now defines a bogeyman cluster of The Worst Diseases Possible. It seemed possible they could be human epidemics, if small ones. This was enough to be scary. But it wasn’t quite as scary as a Game Over.

Having done all this work to set the scene, let’s talk about the book itself. It’s great! I really dig it.

Like all the best nonfiction, it’s a cavalcade of characters. Fiction is leashed by verisimilitude. We have some loose expectations of “how the world works”, and dismiss fiction as unrealistic if its events are too bizarre, its coincidences too forced, or its characters just that much larger than life. God does not care about any of this, and works with the trust you will believe what he says.

Accordingly, The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is beneath all else a “character-driven narrative”. It first introduces us to, of all poetic things, a fallen noble-blooded Venetian family. The money ran out, you see – not because of profligate spendthrifts or revolutionary uprisings, but because of whispers, taunts, that its members were cursed to go mad. In midlife, it seemed, a strangely high fraction of them were struck by a specific sort of insanity. It started with a fever that never quite let down, even after any supposed illness should have ran its course. A little trouble sleeping – but is that so unusual, for someone feverish in the languid Italian summers?

At first, perhaps, this could permit a paradoxical productivity. D. T. Max traces (he thinks) the first description of the family’s disease to a doctor who died in 1765. For a scholarly man in that era, less time spent sleeping may well permit more time pursuing one’s plans. “In the beginning,” he writes, “the feeling might not have been unpleasant—he could stay up all night playing cards or maybe read Morgagni’s famous comparisons of the body to a machine, published just a few years before.” Many of us scheme against the God of Sleep, trying to fight its teeth and claws, eke out more power from days and nights that would otherwise slip away. But we let it win, eventually. What happens if you can’t let it win?

The first part of the book is DTM’s pseudobiography of this doctor, and it presents a fascinating story – all hypotheticals, but all driven by what a learned man in the mid-eighteenth century could have thought while watching his body and mind betray him in a way no one else’s ever had. The story is beautiful, crossing the streams of fiction and nonfiction in an impossible way. As the disease wore on, DTM speculates, our physician friend would start thinking it a curse rather than a blessing. As he soaked through his clothes, his servants would find themselves pouring through his wardrobe several times a day for new shirts. He would guzzle wine, the supposed treatment for insomnia, and find himself drunken but no more capable of sleep; his limbs would grow heavy and his mind exhausted, but he could never cross the divide. He might try to leave the noisy city of Venice for quieter pastures, and find himself no more relieved. He could consult with his colleagues, and none of them would know a word more than he did; in all likelihood they would know far less, the curse of everyone interested in medicine and experiencing something beneath its umbrella.

The disease would wear on inexorably, no matter what he tried. He would find himself trapped in illucid places between waking and sleeping, never quite dreaming, never quite not dreaming. His fever would never abate, but it would gyrate – the fevers typical of the disease, we know, are marked not by consistent high temperatures but by impossible fluctuations, jumping rapidly between every possible extreme. Even today, they look like measurement errors.

When he died, no one would know what to call it. They didn’t know what to call it in his nephew1, or in any of his nephew’s children or grandchildren. As the disease spread across generations, it took upon thousands of names – every wasting disease, infection, or psychosis you could find. It wasn’t exceptionally good for the family’s prospects; the repeated deaths of able-bodied adults made the family poorer, and neighbours refused to marry into the “mad” bloodline.

A point about prion diseases that D. T. Max likes emphasizing is that they don’t steal your reason. Everyone was unanimous that across multiple prion diseases – fatal familial insomnia itself, but also many forms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob, and plenty of other things you could grant such a name – the afflicted were consistently aware of their fates, even in the worst reaches of the illness. Many people with FFI never lost the ability to talk at all, and could express this very well for themselves. Others did, but seemed to know their surroundings infaillibly. There is a famous case report about a man with FFI who managed to slow the disease’s progression with a slew of treatments; he could consistently describe his state in his most “incapacitated” periods when remitting. I’ll let him speak for himself:

(This report was, as it happens, published in the exact same month as The Family That Couldn’t Sleep.)

DTM came to know the family well. He befriended them by way of two members of their younger generation, Lisi – a woman terrified by the shadow of the disease, and Ignazio – the doctor she had married, who was more terrified by the shadow of the disease. Ignazio put together the pieces of the family puzzle, consolidating all the disparate diagnoses into a single disorder and filling out a lot of blank spots on family trees. When DTM came along, he was able to help Ignazio make the case that the family would benefit from the spotlight – that greater awareness of FFI could lead to a cure both for them and for a slew of other prion diseases.

As it so happens, he is one of those nonfiction authors who serve as a character in their own story. DTM has some form of progressive muscular palsy. He is, or at least was in 2006, not entirely sure what it is. The relatively unimpressive state of genetics at the time had not identified his causative mutation, though it looked a lot like one of the rarer forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease2. DTM is pragmatic about this, the way everyone chronically ill is either pragmatic or doomed. Whatever he has, it is a defect in protein structure; his peripheral nerves decay not because of a problem with the nerves themselves but an inability of their scaffolding to hold them together, as he puts it. The last chapter of the book dwells on this, on the web of connections popping up between a thousand disorders. DTM’s disease is something vaguely similar, if you squint, to an exceptionally slow-progressing motor neurone disease; if you jump another level out, you see amyloid plaque diseases like Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s, and if you jump yet another level out, you see something like prions. His interest in the Venetian family was driven by this. Some of its members thought this a beautiful act of sympathy; others thought him a grotesque parody of themselves, an onlooker, a gawker, peddling their tragedy to salve his relatively insignificant problems. They are, he thinks, both right.

That’s the beginning, and that’s the end. What happens in the middle?

---------------------------------------------------------

The Venetian family lends the book its title, but they’re really more of a framing device. The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is separated into four parts, of which the first and fourth – the shortest by far – deal with the family. Part 2 is kuru, the king of fucked up diseases you read about in clickbait Weird Medicine listicles. Let’s talk about kuru!

Kuru, is, famously, the prion disease you get if you eat another person’s brain. Well, not quite. It’s a prion disease that became endemic amongst women in the Fore society, who ritually ate brains, one of which had an inherited or spontaneous prion disease. This is an important note – there’s a tendency (which the book’s later chapters engage in) to assume cannibalism just has a Prion Disease Generator attached. If you eat people who don’t have prion diseases, you won’t suddenly get one. Uh, don’t eat people.

Anyway, part 2 is DTM’s historiography of Fore-Westerner first contact. It’s hilarious. Papua New Guinea is a frankly ridiculous place; one of the all-time best Lyttle Lytton winners (worst first sentence from a hypothetical or, in this case, real work) was “Papua New Guinea is so violent that more than 820 languages are spoken there”. The native residents were so hostile to outsiders that all the colonial empires had cut their losses – and when you think about the places they colonized, that says something. After the First World War, PNG was ripped from its nominal German ‘owners’, but no one else wanted the place.

So, of course, they gave it to the Australians.

It was thirty years and another war before we actually made contact. 1940s Australia was as ‘settled’ as it’d ever be; the cities were bustling and the interior was mapped. The kind of explorer who two centuries before would be heading to new continents had to console himself with Pacific islands. Console he did. The native peoples of the PNG coasts were hostile enough to the wannabe-colonialists that the Australians, flying planes overhead, were the first people to discover that the island’s inland was populated too. No one had broken through on land.

In all this deep and angry rainforest, the Fore were the furthest out. They lived far into the island’s mountainous interior; DTM describes their territory as “nearly vertical”. Calling people primitives is a bit passe these days for understandable reasons, but no other term comes to mind. The Fore had no name for themselves; we call them by an exonym, “the people to the south”. They weren’t, to be clear, hunter-gatherers – they were slash-and-burn agriculturalists, but very well-fed ones. Despite the tendency in grain-focused cultures for poor agriculturalists to be stunted/malnourished, the Fore were a remarkably healthy people.

Well, except for the famous bit.

The first remarkable thing about the Fore was just how quickly they wanted to assimilate. Most PNG tribes weren’t particularly enthused by Western offers of injections/tractors/radios/Christianity. Yet as soon as the Australians arrived, the Fore made ceasefires in their wars with other tribes, volunteered to help large-scale Australian projects on the coast, started planting and trading coffee, and enthusiastically participated in censuses. It’s the only first-contact narrative I’ve seen where the colonizers were concerned about how badly the other guys wanted to be colonized.

The next was the one that got their names in the history books. Australian officials started to notice a remarkable lack of women in Fore camps. Some tribes sequestered their women, particularly when Westerners were around, so at first they thought nothing of it. The high rate of unpartnered young men, though, was way out of PNG norms.

DTM tells this part fantastically. The Fore chapters drip with the dread of dramatic irony. When the first breakthrough comes, you have to catch your breath:

“Tiny” Carey noted something in the middle of August 1950 that deepened this mystery. He noticed that near the village of Henganofi there had been an unusual number of deaths. “It appears,” he wrote his superiors, “natives suffer from stomach trouble, get violent shivering, as with the ague, and die fairly rapidly.” [...] McArthur investigated a little more [...] One day in August 1953 he ran into more of the shivering people Tiny Carey had seen several years before: “Nearing one of the dwellings, I observed a small girl sitting down beside a fire. She was shivering violently and her head was jerking spasmodically from side to side.”

It would be quite some time before anyone figured out what caused it – but the problem, as DTM notes, was that its cause wasn’t possible. Everyone priored that the weird undescribed disease in the Fore lands was some nocebo sorcery-sickness. Vincent Zigas, the first actual doctor sent to work with the Fore, tried to placebo-effect them and failed miserably:

On the way, Apekono stopped at a hut and showed Zigas his first kuru victim. “On the ground in the far corner sat a woman of about thirty,” the doctor wrote. “She looked odd, not ill, rather emaciated, looking up with blank eyes with a mask-like expression. There was an occasional fine tremor of her head and trunk, as if she were shivering from cold, though the day was very warm.” It was almost exactly the tableau McArthur had witnessed in 1953. Zigas, though, was a doctor. He could do more than look—or so he thought: “I decided I might as well try my own variety of magic,” he remembered. He rubbed Sloan’s Liniment, a balm for sore muscles, on her and declared to her family and his guide: “The sorcerer has put a bad spirit inside the woman. I am going to burn this spirit so that it comes out of her and leaves her. You will not see the fire, but she will feel it. The bad spirit will leave her and she will not die.”

The lotion penetrated the woman’s skin and she writhed in pain. “Get up! Walk!” Zigas commanded theatrically. “The woman struggled feebly as if to rise, then, exhausted, started to tremble more violently, making a sound of foolish laughter, akin to a titter.” That evening Apekono asked Zigas not to try to cure any more kuru victims; “Don’t use your magic medicine anymore. It will not win our strong sorcery.”

This was a disaster. The Fore were so cooperative precisely because they hoped “Western magic” could conquer theirs. As it became clear it couldn’t, they turned hostile. The Australians had hoped to “modernize a Stone Age people”; now all their subjects were dropping dead before their eyes, from what they could only assume was a “hysterical reaction” to colonization itself.

So, to solve this, they needed a batshit insane American.

Carleton Gajdusek is one of the characters who dominates The Family That Couldn’t Sleep. He couldn’t not. You could put him in a car commercial and he’d dominate it.

Gajdusek was a physician with a rare, intense combination of science and practice. He was a romanticist, a field worker, and a lover of everything strange. He’d been an army doctor, a government conspiracy-cover-upper, and a postdoc under Linus Pauling who described his intent as “to straighten out Pauling’s ideas about proteins”. He hated civilization, in a slightly-to-Ted’s-centre sense, and was passionate about “primitives and isolates”. He jumped at the chance to work in Papua New Guinea; he planned to conduct a multi-site study on child development in such cultures, and relished the opportunity to live in a “primitive” environment himself.

He did all this so he could rape kids. Oh, he did it for the scientific curiosity and love of medicine, but he also did it so he could rape kids. Gajdusek was a pedophile in the actual-lifelong-exclusive-paraphilia sense, as opposed to the “metonym for child molester” sense. Some people who roll snake-eyes on the Sexuality Dice repress it, but some are perfectly happy to act on it; Gajdusek was #2 in its fullest form, the kind of guy who believes that a well-lived life includes raping some kids. DTM doesn’t shy from this, not for a moment. It’s the first thing he tells you about Gajdusek. It couldn’t not be; you couldn’t talk about why he went to PNG otherwise.

When Gajdusek landed in PNG, he first found the place too civilized. He’d been promised a land of “cannibal savages” – where were they? After some traipsing, he found them, right where he was promised. The Fore were perfect for Gajdusek. They had some kind of medical mystery that’d been lost on everyone else. They ate each other, in exactly the way he loved detailing in his diaries (“”Women and children, particularly, partake of the human flesh,” he noted with pleasure”). As kuru cases popped up, he aggressively recorded them. He wrote lovingly detailed notes that he sent back to his Australian advisor. He wrote with intensity, with exclamation marks, with the joie de vivre of a man just where he wanted to be. Gajdusek smothered the Fore with ‘cures’ that never worked, but they didn’t get angry at him. As DTM dryly puts it: “Their children trusted him, and that was enough for them.”

At some point, someone suggested sending an anthropologist...or an epidemiologist...or literally anyone with more credentials than Gajdusek and Zigas3. Gajdusek threw a shitfit, convinced this one-and-a-half-man team was enough to Solve The Problem Forever. But he got bored eventually – running off with another tribe with, as his diary notes at length, an apparent custom of youths ritually fellating older men – and Zigas, I dunno, the book neglects him a bit here. So they managed to sneak in some anthropologists.

The husband-and-wife team of Robert Glasse and Shirley Lindenbaum4 were the first involved parties to give a shit about the Fore as people, rather than as colonial subjects/medical mysteries/walking sex toys. What they uncovered was fascinating. The Fore were cannibals, yes, but they were recent cannibals.

They didn’t have an ancient tradition of eating their dead, like the other visitors assumed. They happened to be in contact with some cannibal groups, and after a Fore man died of “sorcery”, they thought: well, what would happen if we ate him? “People tasting it expressed their approval. ‘”This is sweet,” they said, “What is the matter with us, are we mad? Here is good food and we have neglected to eat it.”” If not for the wild coincidence that the first Fore cannibalism victim had a prion disease, kuru would never have existed.

Glasse and Lindenbaum started to put together the pieces. They’d been sent down to rule out a genetic explanation – to track the kinship ties of the Fore and see how the disease ran through families. It didn’t run through families in any coherent sense, but it sure did run through cannibalism. The clincher was the age distribution. The Fore, ever enthused by colonialism, quit eating each other as soon as the Australians arrived. Children stopped dying of kuru shortly after; they simply weren’t exposed to the infectious agent.

The couple sent the news to Gajdusek, who was off raping kids somewhere else. In the next part of the book, DTM runs through Gajdusek’s many conjectures of kuru’s cause – more like sketches or abstract paintings than like true hypotheses. Gajdusek was annoyed that someone else was doing something he “totally could’ve done”, and even more annoyed that another lab was running similar experiments – an attempt at a vaccine for a particular sheep disease had accidentally created a prion generator. But he was happy to swoop in and claim the credit for what he was starting to think of as “slow viruses”, an infection that somehow lays dormant for years.

DTM portrays Gajdusek perfectly, in that “real life has no need for verisimilitude” way. Gajdusek was at once a brilliant man, an all-consuming narcissist, an entertaining character, and a monster beyond redemption. A lesser book might pick one or two. The Family That Couldn’t Sleep portrays him as all four, and on a personality level (as opposed to a scientific one), the Gajdusek-focused parts are some of the most gripping.

---------------------------------------------------------

Outside of the jumps between the Venetian family and everything else, The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is not siloed. The narratives of all prion diseases are deeply intertwined. This is what makes it a great book. It’s 300 pages of dramatic irony. You read the whole thing, waiting for the eureka moment – the point everyone realizes they’re looking at the same cause. It does, however, make it a tad difficult to review or synopsize. The book’s story is so weird – and, often, so at odds with conventional wisdom that trickles down about the Fore et al – that you have to recap quite a bit, and the book steadfastly resists recapping.

The next couple chapters after we depart from Gajdusek’s credit-claiming are mostly about experiments with various prion diseases. They’re scientifically fascinating. Unlike some medical-books-for-general-audiences (cough, How Not to Study a Disease), DTM never talks down to the reader. He assumes someone reading a 300-page book about prions is smart and wants to learn about prions. He also has – you can feel it in his words – the agonizing experience of spending his life on the other side of the doctor’s desk, trying to beat into whoever he’s talking to that no, seriously, you don’t need to lie to him or try explain a complex disease at a fourth-grade level.

The first prion disease studied was scrapie. Scrapie was a big deal – it starved and killed large shares of British sheep flocks, making it a serious economic problem. Veterinary researchers had tried to prevent or cure it for centuries. It was a veritable graveyard of ambitions:

Quintessential was D. R. Wilson at the Moredun Institute in Scotland, who worked in the middle of the last century for more than a decade trying, with mounting frustration, to kill the scrapie agent. He found that it survived desiccation; dosing with chloroform, phenol, and formalin; ultraviolet light; and cooking at 100 degrees centigrade for thirty minutes. The scrapie researcher Alan Dickinson told me he remembered Wilson at the end of his career as “very, very, very quiet. Of course, that was after his breakdown.”

“Now it is our turn to study prions. Perhaps we should approach the subject cautiously.”

The problem, as DTM explains, is that prion diseases were impossible. They violated 20th-century understandings of biology. Proteins “were no more alive, and no more infectious, than bone”. Prion diseases seemed to have too many causes – genetic, infectious, and sporadic. They looked infection-like in some ways, but patients didn’t produce virus antibodies. Sheep exposed to scrapie, or chimps infected with kuru, took years to develop symptoms. Their facts did not fit together.

In the 1960s, people started wondering. The unifying trait of prion agents was that they had to be denatured to be destroyed. Was this a particularly small virus defined by its protein coating? Or – even more outre – was it pure protein, no DNA at all? No one could figure out quite how the latter worked, but it was tempting. Gajdusek, by now a major figure in this field, kept a foot in both worlds. He didn’t want to stake his reputation on a no-DNA hypothesis, but he certainly sympathized.

Enter Prusiner. Stanley Prusiner was Gajdusek’s counterpart. Where Gajdusek seemed permanently manic, Prusiner was deliberate and exacting. He entered Gajdusek’s “slow viruses” field in the early 1970s after a chance encounter with a CJD patient. He relished the laboratory in a way Gajdusek didn’t at all, and set out to optimize the hell out of his projects.

Prusiner set out to isolate the smallest infectious particle in the scrapie agent. He injected tons of hamsters (hamsters got sick faster than mice) with increasingly tiny scrapie proteins, hoping to determine whether the Minimum Viable Scrapie was DNA. By the mid-1980s, he’d produced something so small it couldn’t possibly be a virus. Denaturing it destroyed it; exposing it to nucleic acid dissolvers actually made it stronger.

Emboldened by this discovery, Prusiner set out to anoint himself the King of Prions. Here emerges something of a Voldemort-Umbridge distinction – the difference between cartoonish villainy and banal evil. Gajdusek is a bad guy because he rapes kids. Prusiner is a bad guy because he is the most grotesque stereotype of the Advisor/Peer Reviewer from Hell made flesh. Everything Prusiner did was to build his reputation atop a pile of skulls. When recruited as a peer reviewer for other prion papers, he wrote negative reviews to undermine their authors. He worked his grad students to the bone and intentionally destroyed their careers, telling them he’d “ruin them” if they entered prion research as competitors. He lied about the origin of the protein-only hypothesis, claiming he originated it a decade after it was actually conjectured. But hey, he was good at getting grants.

I was surprised reading a lot of this, because for all the time I’ve been aware of it, the cause of prion disease has seemed settled. “Oh yeah, it’s a protein that gets all fucked up.” But DTM goes through just how unsettled it was right up through to The Family That Couldn’t Sleep’s publication. Serious confirmation only arrived a couple years later. Many people were deeply critical of the prion hypothesis – often, it seemed, because they loathed Prusiner too much to go along. Throughout the book, he cuts an uncharismatic figure.

Gajdusek and Prusiner both won the Nobel for discovering prions, decades apart. This tells you something – the “discovery” of prions can be construed quite a few ways. Gajdusek formulated the hypothesis; Prusiner proved it. Gajdusek was grievously offended by Prusiner’s Nobel, perceiving his rival – not inaccurately – as a follower who never originated any ideas of his own. But Gajdusek was offended from a federal prison cell, so how’d that work out for him?

Fascinating as all this is, no one published a book about prions in the mid-2000s because it was about kuru or FFI. They published books about prions because teenagers were dying, and people wanted to know why.

DTM lays the seeds for part 3 – the mad cow section – in part 1. This is a discussion of scrapie, the longstanding prion disease of sheep. Scrapie was a medical mystery for centuries (remember poor D. R. Wilson), precisely because of the intuitive implausibility of prions. The scrapie chapter is a great history-of-science piece, covering the agricultural productivity revolutions of the 18th century, the surfeit of bizarre origins veterinarians concocted, and the treatments that never worked.

Scrapie is not transmissible to humans – well, we hope. It’s concerningly transmissible to primates. But it’s been around for a long, long time, and it doesn’t epidemiologically look like humans get it...we hope. Anyway, you ever tried to generalize from one example?

The British government did! In the mid-1980s, strange reports started coming out of the UK’s farms. Farmers were describing a new disease where dairy cows – incredibly docile creatures, under normal circumstances – turned hostile, kicking them as they went into the milking stalls. The symptoms looked to all the world like scrapie. Epidemiologists tracing the outbreaks found a unifying link with “cake” – animal protein feed sweetened with molasses. The scrapie-like symptoms must have traced to an infected sheep. But scrapie doesn’t transmit to humans, so it must be okay to keep slaughtering them, right?

We all know how this ended.

The best term for the British response to the mad cow outbreak is “cacklingly evil conspiracy”. The agricultural industry really, really didn’t need a huge zoonotic outbreak – so it decided it didn’t have one. They first suppressed all mentions that the disease looked like scrapie, then – when this became impossible – hyped up that scrapie doesn’t transmit to humans, so there’s nothing to worry about. The formal name of the disease, “bovine spongiform encephalopathy”, was supposedly chosen to optimize for unfamiliarity – it wouldn’t fit well in a headline. They emphasized, extensively, that there was nothing to worry about. Ever.

At some point, people started asking questions. If there was nothing to worry about, why was the agricultural industry panicking so hard? As things became ever more worry-inducing, this turned down ludicrously twisting paths:

Meanwhile, the Southwood Working Party and the experts who advised it were learning on the job. They learned, for instance, that the BSE agent entered the animal through the mouth and then followed the digestive tract into the organs that try to filter out infections—the tonsils, the guts, and the spleen—and from there traveled into the peripheral and central nervous system, and finally arrived at the brain. They also learned that pasties, meat pies, and even some baby foods contained tissues from a lot of those organs. So the Southwood Working Party recommended banning these organs, but only from baby food. This started a chain reaction of consumer doubt: if infected cow organs were unsafe for babies, how could they be good for adults? The government then banned offal, as the organs were collectively called, in all human food but gave the industry a grace period to get it out of the feed supply. Then pet food manufacturers began to wonder if what drove cows mad might not also drive dogs, cats, and parrots mad. The feed they sold came from concentrate made of the same sick animals that had previously made up the meat and bone meal farmers used. Their trade group decided to put a similar ban in place—immediately. So for five months it was safer to be a dog than a human in Britain.

DTM spends pretty much this whole section of the book making fun of the British government. To be fair, they deserved it. They killed hundreds of kids in agonizing and preventable ways – they could take some ribbing.

This is all throughout the mid-1980s to early-mid 1990s. Through this period, it wasn’t yet clear that mad cow could spread to humans. The panic was clear, and deserved, but it didn’t yet have a match for its powder keg.

It would alight. The first suspected case of vCJD – human mad cow – was in 1994. Fifteen-year-old Vicky Rimmer developed a sudden, strange disease. Doctors gave her months to live...until she died in 1998. A couple other suspected cases trickled down through the mid-90s, including a young man who made meat pies for a living, whose grieving mother received a letter from the Prime Minister that “humans do NOT get mad cow disease”. (That must’ve been fun.)

Soon, they couldn’t deny it any longer.

On March 20, 1996, Stephen Dorrell, the health secretary, stood up in Parliament to announce the news that had already appeared as a tentative conclusion in scientific journals and as rumor in newspapers for the previous two years: British beef was killing British teenagers. The first confirmed death was that of Stephen Churchill, a nineteen-year-old student from Wiltshire, who died in May 1995. Back in 1989, at the Southwood Working Party’s suggestion, the government had set up a surveillance unit in Edinburgh to watch for any evidence that BSE had crossed to humans. One worry had been that if BSE passed to humans, how would anyone know it? How would you recognize something you had never seen? It turned out to be easy: Churchill and the nine other teenagers who had gotten sick had spectacular amyloid plaques in their brains, chunks of dead protein almost visible to the naked eye. If sporadic CJD was a whisper, BSE-caused prion disease was a shout. The investigators sat open-mouthed looking at slides whose damage, they feared, portended the most severe epidemic in modern British history.

This part of the book is not fun. It lacks the insane personalities and duelling careers of the other entries. It is an honest chronology of the vCJD epidemic – a gruesome failure of the agricultural industry, the one system that everyone is vulnerable to. The government and industry had completely violated their duty of care to citizens and consumers. They were paying the price. No one would buy British beef anymore – not while they watched their children die.

Now here’s the thing: this is ethnography, not historiography. The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is a book from the mid-2000s. The epidemic was not at all in the rear view mirror. There were piles of unanswered questions that DTM constantly alludes to. We have eighteen years more hindsight than he did then. What do we know now?

---------------------------------------------------------

In 2006, the vCJD epidemic looked like it was going to be a lot better than the worst fears. BSE itself was a huge problem for the cattle industry, but honestly, no one is too sympathetic to the cattle industry. People were not going to die in anywhere near the numbers believed. We had all sorts of reassuring data coming out about this, which DTM chronicles. We were learning that only some genotypes seemed susceptible to vCJD. We didn’t see any older people die of the disease. We were seeing numbers drop, such that vCJD must have a pretty short incubation period.

Anyway, all of this is wrong!

The Family That Couldn’t Sleep was written in the candidate gene era. Back then, the nascent field of human genetics was sure it was about to Solve Polygenism. Yes, the simple Mendelian monogenic patterns popular a few decades back clearly didn’t apply to common diseases, but how many variants could there be? We were about to discover the five genes influencing 20% of Alzheimer’s risk each, the five genes influencing 20% of heart disease risk each, etc., and once we were done we’d just do gene therapy and cure Alzheimer’s. A paper on autism genetics from 1999 was so outre as to speculate there might be as many as fifteen genes involved. The fact we are now using the term “omnigenic model” should tell you roughly how well this worked out.

Do you remember SNPedia? If you were a 2014 Slate Star Codex reader, you might. 2014 was still pretty candidate gene. People were out there publishing papers saying a single variant could increase your life expectancy by 15 years. SNPedia was a site that beautifully categorized all of these, so you could do 23andme or whatever, look up your results on SNPedia, and make horrible life choices.5 It was eventually bought out by one of the consumer DNA companies, so no one ever edited it again, making it a great time capsule of early-mid 2010s behavioural/medical genetics takes.

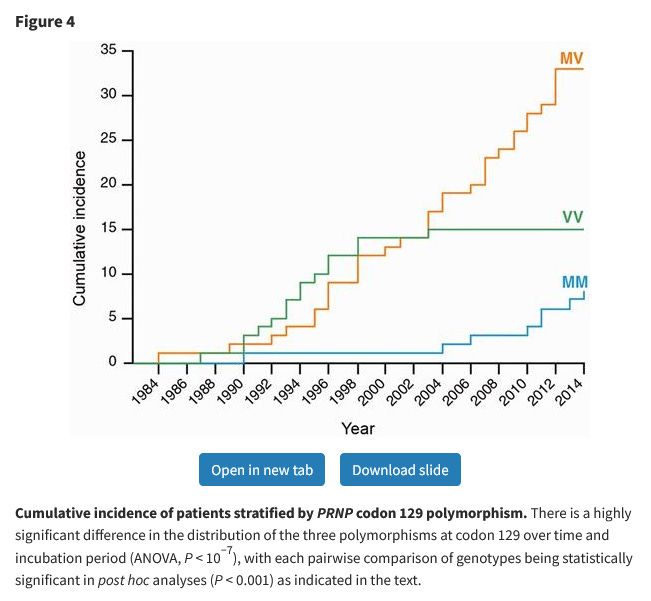

SNPedia will excitedly explain to you that common genetic variants make you immune to vCJD. They cite a 2009 post from the now-archived 23andme blog titled “No Good Evidence That Potential Pool of Mad Cow Disease Victims Is Expanding”, explaining how fears of late-onset vCJD are clearly debunked by new Scientific Knowledge. Everyone who developed vCJD in the 1990s and 2000s had an M/M genotype in a particular part of the PRNP prion gene, so the roughly half the population with M/V or V/V genotypes were immune.

The Family That Couldn’t Sleep buys this, too. In fact, it buys it in an even more agonizingly 2000s way. The first sign that transmissible prion diseases weren’t genotype-restricted should’ve been the growth hormone kids. You might have heard this story – from the late 1950s through mid-1980s, human growth hormone produced from brain tissue was used as a treatment for pituitary dwarfism, until it turned out to spread CJD if the originating brain was infected.

DTM discusses this, to set the scene for the genetics thing. He mentions what was the state of the art at the time – that a disproportionate share of both the growth hormone kids and sporadic CJD cases were V/V homozygotes. This, uh – so the book was written in the mid-2000s, yeah?

The conclusion DTM drew – and this was a common conclusion at the time – was that homozygosity somehow made you more vulnerable to CJD, and M/M homozygosity made you vulnerable to BSE-borne CJD in particular. We cannot criticise the author for not predicting the future, but we live in the future, and can say how this worked out. Turns out, nope, M/V heterozygotes totally get vCJD. After a British man in his 30s died of CJD in 2016, he was found to have vCJD and an M/V genotype. He was tested for vCJD only because he was exceptionally young for someone with a sporadic prion disease – meaning people developing it later in life would be missed6.

Did you know up to 1 in 2000 people in the UK have latent vCJD?

There is one line in The Family That Couldn’t Sleep that stopped me dead in my tracks when I read it:

What happens to the Italian family in the end depends less on their own actions than on the world’s interest in prion diseases, which they cannot control. If lots of people are afraid of getting variant CJD, the family benefits. If fear of prion disease goes the way of the fear of swine flu or Ebola, then they will be orphaned again.

THIS BOOK IS FROM 2006! Three years before the swine flu pandemic! Eight years before the Ebola pandemic! “If you’re looking for a sign, this is it.”

---------------------------------------------------------

The last section of The Family That Couldn’t Sleep addresses BSE fears in America and a nascent internet subculture DTM calls “Creutzfeldt Jakobins” – people who track American CJD cases, trying to spot vCJD patterns. When reading his description of the Creutzfeldt Jakobins, my mind constantly, uncontrollably turned to covid. Here it was – an online community of people deeply skeptical about a disease’s official story, tracking every contradiction, every implausibility, every statistic that failed to apply to the individual. Self-described “redneck hippies” and “soccer mom Republicans” teaming up to find the truth hidden behind an impossible world. You know what they’re doing now.

I’ve always combined a deep interest in medicine with a healthy distrust for it. People who are constitutionally inquisitive, anti-authoritarian, and suspicious about official narratives tend to end up skeptical of at least some mainstream claims in the field. This is not to say I think you should take bleach enemas or something, just that I understand the impulse behind concluding the US government was covering up a local vCJD wave.

Traditionally, sporadic prion diseases are said to have a prevalence of one in a million. (Hold on to that for a second.) The last section of the book is a chronology of Americans finding bizarrely more than one in a million of their friends dying of sporadic CJD, often at inexplicably young ages, sometimes in geographical clusters. This is understandably suspicious. Then DTM goes on to reassure us by saying none of these cases were confirmed to have an M/M genotype, which OH GOD OH FUCK

A number of high-profile people in the prion world, including Gajdusek, are clarified as not believing sporadic prion diseases exist. You get the impression DTM doesn’t, either. Now, how common are prion diseases?

Eric Vallabh Minikel has an answer for you! Eric and his wife Sonia are prion researchers from a rather unique background – after Sonia was diagnosed as having a single-gene mutation with ~100% penetrance for prion disease, they left their previous jobs to dedicate their lives to curing it. It turns out, when you run the numbers, you get not one in a million but 1 in 5000 people dying of prion diseases.

This is best described as “nightmarishly high”. I’m normed on genetic disorders. A genetic disorder that affects one in five thousand people is pretty common! I have known, in person, completely unselected, just from “random people I’ve met in my life in a non-medical context”, someone with a ~1/250k syndrome and someone with a ~1/50k-100k syndrome. I don’t think anyone in my extended family knows someone who died of a prion disease. I feel like it would’ve come up if they did!

Prion diseases have distinctive phenotypes. Not distinctive enough, apparently, to avoid a lot of CJD being misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s – but diagnosis is consistently insane. Something DTM reiterates throughout The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is just what prion dementia looks like. The characteristic dementia in prion diseases spares something – “self” or “recognition” or “reflection” – that is not spared by Alzheimer’s, or by most common dementias. Shouldn’t this be, uh, noticeable?7 They kill rapidly, often over the course of months, and often onset in midlife. ALS shares this pattern and is way, way more common than prion diseases; you hear about ALS far more in the “disorder people actually have” sense. What am I missing here?

Anyway: 1 in 2000 prevalence of latent vCJD in the UK + extreme lack of clarity over whether scrapie is human-transmissible + blood donations spread vCJD + sporadic CJD prevalence keeps going up = ???

(Yes, I am annoyed that most countries have lifted their ban on UK blood donors, thank you for asking!)

---------------------------------------------------------

But back to the book. The “American chapter” is one-third about the country’s response to vCJD, one-third about the Creutzfeldt Jakobins, and one-third about chronic wasting disease. The last part is the most interesting.

Chronic wasting disease is a prion disease of deer. Like scrapie, it “probably, we hope” isn’t human-transmissible (eat venison at your own risk). Under natural circumstances, deer shouldn’t get prion diseases:

A prion plague should not be possible among ruminants in the wild. Deer are not cannibals, as the cows that spread BSE were forced to be; and, because deer and elk are not domesticated, they do not have enough contact with one another to spread a prion infection the way sheep are thought to spread scrapie. But deer do not live as they used to live, humans having once again brought their ambitions to bear on the natural course of things.

The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is a book of medical anthropology. Anthropology of the Veneto, anthropology of Papua New Guinea, anthropology of 1990s Britain. Here, it is an anthropology of America. Americans, having won the world, still fight to win their own backyard. The North American continent is geographically diverse, cutting through rain-snow-shine, mountains jutting over plains, cities sprawling into wilderness, habitations criss-cross dotted with surprisingly few empty zones. Go somewhere like Denver, the Mile High City, three million people fighting against nature. Few other countries have anything like this; geographically vast polities usually have uninhabitable blocks. Australians are twenty-five million people clustered against the shore. It still surprises me, after all this time, how every US state has a meaningful city8.

Midcentury Denver, growing and sprawling out across its mountains, started to run into their natural inhabitants – deer.

Starvation is one way nature adjusts the deer population to the available food supply. People did not usually see this process, but in the 1950s and 1960s Colorado became more densely settled, reducing forested areas and forcing deer to look longer and harder for food. At the same time, the state enacted conservation laws, limiting when and where hunters could shoot. Soon emaciated deer began wandering onto the lawns and through suburban streets looking for a meal. People began to feed them, only to find that they died anyway. They would drop dead by haystacks, along highways, and in flower beds.

In the late 1960s, a young biologist named Gene Schoonveld tried to figure out why the deer starved even when they were fed.9 He deprived some deer of food for a while, “[h]e cut windows in their stomachs to see what went on inside, and then he began to feed them”. While this was going on, he had a control group of healthy, well-fed deer as backups in case anything went wrong. It did...but not to the experimental group.

The pen in which the deer were kept also housed sheep, which, it turned out, were scrapie carriers. The deer somehow acquired scrapie – there’s a huge unanswered question here, which DTM doesn’t address. How did they get scrapie? They didn’t eat the sheep, presumably. Did it somehow transmit from casual contact? This is not supposed to happen. And yet: the deer in the sheep pen started dying of a mysterious scrapie-like disease, one never reported before, that would go on to infect thousands.

These deer were released into the wild. Ten years later, the first reports of chronic wasting disease came out. The disease spread across deer and elk in the western half of the country. By the turn of the millennium, cases were exploding – and lost all geographical restriction. DTM can report up to 2005, at which point it was floating around Upstate New York.

This kind of spread doesn’t track natural deer migration. That’s irrelevant, because nothing about CWD’s spread is natural. We shift gears into an anthropology of the American hunter. The hunter wants to shoot the most impressive buck, to bag himself one with as many “points” as possible – one whose antlers branch out most. A “ten-point buck” has five branches on each horn:

Nature doesn’t make enough bucks with perfectly symmetrical ten-point horns. To fill the demand, the market had to step in. Thus was born the deer farm industry, which raises captive deer in better genetic and nutritional conditions than Nature permits, then ships them across the country so hunters who couldn’t get legit ten-point bucks get the taxidermy piece for their wall. These are controversial amongst hunters and illegal in numerous states – but the industry is big enough to spread CWD. (The kind of hunter who needs a deer shipped to his house is the kind of hunter who will fumble killing it.) Another problem is supplemental feeding – leaving out protein-enriched food for deer to eat. This produces “trophy class animals at an earlier age”, but again, what’s in that protein? (“It is much like feeding your cows 41 percent protein cottonseed cake during the winter to raise the protein level in the cow’s diet to a level that will maintain acceptable production”, says that article from 1991.)10

The book segues into a vignette. CWD was new in Wisconsin in the early 2000s, and the state’s Department of Natural Resources was optimistic it could eradicate it. In a state with a love of hunting, you could, in theory, recruit people to kill every single deer in a 400-square-mile radius:

In many states, the state would have had to call out the National Guard for such an onslaught, but hunting is a passion in Wisconsin. Hunters shoot 450,000 deer every year, more than in any other state. “I’m looking for ardent hunters to help us, unless fear or their wives keep them away,” one DNR official told a Milwaukee magazine. The state extended the normal hunting season and waived the usual limit of one buck per hunter, and the hunters came out in force.

The whole affair was gruesome – one official called it “hunting for slob hunters”. If you’re trying to eradicate a prion disease, you can’t very well let people take the carcasses home to eat. Bodies piled up in control stations, decomposition mingling with bleach. The 2002 hunt established a base rate of 2% for chronic wasting disease in Wisconsin deer, with the most affected areas getting up to 10%. Further hunts in 2003, 2004, and 2005 spread to wider and wider areas – and didn’t move the needle one bit.

This is to say that CWD is quite a bit more common in the American deer population than BSE ever was in British cattle. Since publication, it’s popped up in Norway and South Korea. Notably, Norway doesn’t allow for the import of cervids, raising numerous questions about how it got there. There are no unambiguous cases of CWD transmission to humans, and in vivo/in vitro primate studies have mixed results. There sure are some unusually young hunters with sporadic CJD, though. But don’t worry, most of them aren’t M/M homozygotes!

There is an absolute ton going on in this book. I’ve had to skim over whole sections. Parts that couldn’t be easily slotted into a narrative review include:

When Gajdusek was invited to a party at Prusiner’s house, he was horrified to find his rival had purchased hundreds of New Guinean statues – all with the genitals removed.

Elio Lugaresi, the neurologist who clinically identified FFI, shipped his patient’s brain to his former student Pierluigi Gambetti. Gambetti at this point ran a neuropathology lab at Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland. Lugaresi was absolutely bewildered as to why his student would leave Italy for Cleveland.

The only time DTM ever saw Lugaresi upset was when Lugaresi took him out for dinner at a restaurant specializing in wine, and he had to tell him he didn’t drink it.

The British agricultural minister attempted to force-feed his four-year-old daughter a burger as a photo-op. Later, a family friend’s daughter died of vCJD.

BSE origin theories include: space dust, Gajdusek being a secret CIA operative who infected cows, CJD-infected human remains accidentally getting shipped to Britain as animal feed.

George Glenner, an Alzheimer’s expert and collaborator of Prusiner’s, died of cardiac amyloidosis, where amyloid plaques (similar to those seen in the brain in both prion diseases and Alzheimer’s) build up in the heart. Several of their collaborators suspect he was somehow infected.

Prusiner experimented with quinacrine, the malaria cure, as a potential CJD treatment. He gave a bunch of it to a young woman whose father heard about his research. It stopped her symptoms from progressing – and exploded her liver. “By now, more than three hundred prion disease sufferers have tried quinacrine and, according to Graham Steel, the head of the CJD Alliance in the United Kingdom, “they’re all dead.””

There were internet fora full of people convinced they had vCJD. Minor side notes like “symptoms persisting for several years without decline” or “spontaneous recovery” were not considered contraindications. Some claimed to be cured of vCJD, and shilled various alt-med solutions. “[T]he woman who said she’d been cured responded with accidental ambiguity, “I don’t believe my information gives false hope—at the moment, what else is there?””

“What else is there”, indeed.

I’ve also skimmed over most vignettes of the family. Some of these are real highlights, particularly the explication of Silvano’s illness – the man who brought FFI to medical attention, after decades of misdiagnosis. This is impressively distinctive. His illness does not look like much anything else:

During good moments, Silvano could still read. He wore his glasses on the end of his nose. He ticked off the days on a pad so he wouldn’t get disoriented. He dressed in black silk pajamas with a pocket square and continued to receive visitors.

The nights were not so smooth. At night, Silvano dreamed, re-enacting memories of his old life, just as his sisters had. FFI strips its sufferers not just physically but psychologically. Silvano had always loved social life. He had even found the old crest of the Venetian doctor—black and red with a gold star—and hung it outside his bedroom. Now, in his dreams, Silvano carefully combed his hair, as if for a party. Once he saluted as if he were part of the changing guard at Buckingham Palace. He picked an orchid and offered it to the Queen of England.

During lucid moments, Silvano could laugh with Ignazio and Lisi over what was happening—he joked that the brain-sensor cap on his head made him look like Celestine V, and that, like the thirteenth-century pope, he wanted to renounce his crown—but such joking did not disguise his terror. Two months into his stay at Bologna, he was howling in the night, his arms and legs wrapped around themselves, the tiny pocket square still in place. In the last days of his life he lay in a twitchy, exhausted nothingness.

My thoughts turn back to DF, the FFI patient who swung between total lucidity and introverted serenity. Everyone was enraptured by Silvano’s illness precisely because he didn’t look “demented” in a traditional way, or even an unusually rapid way. This is supposed to be also true of CJD – some kind of lucidity persisting unusually far into the illness, even in a state that in any other disease would be marked by confusion and delirium.

So, let’s close on a question: is Alzheimer’s a prion disease?

Remember, earlier, that we mentioned how pituitary growth hormone treatment can spread CJD. Turns out – probably – that it can also spread Alzheimer’s. Tauopathies – which include Alzheimer’s – seem to be...prion-like, in some way. Prusiner has been banging this particular drum since the 1980s, but hey, that’s part of what “good at getting grants” means.

What is Alzheimer’s? No, seriously, that’s an important question. “Alzheimer’s disease” originally referred to a rare, early-onset dementia. It’s always been characterised by a specific neuropathology, but the value of “specific” here is, uh, not specific, and Alzheimer’s-like pathology is seen in surprisingly many healthy elderly people. The neuropathology of autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s is not always identical to that of the sporadic disease, nor is that of the dementia seen in Down syndrome (also, people with Down’s develop Alzheimer’s neuropathology 15+ years before symptom onset, and some people with Down’s never get dementia despite having the pathology). It’s tricky to avoid the conclusion that modern Alzheimer’s is a wastebasket diagnosis.

Does this mean there are diseases that can operate by the “genetic-infectious-sporadic” prion triad without being prion diseases per se? It’s possible to transmit cancer via organ donation, maternal-fetal transmission, or unhinged experiment; cancer can be genetic (e.g. BRCA, Li-Fraumeni) or sporadic (e.g. most of it). “Prion disease” is probably not the best way to think about cancer. It’s also apparent, when you look at it this way, that what we’re calling “sporadic” is not “you always get it by bad luck with no external influence”; there are unambiguously environmental factors in many cancer cases.

What I’m saying is that we need to redo the pituitary HGH experiments with more diseases My advisor has informed me not to say this.

This is interesting to dwell on. DTM mentions early in the book that modern medicine owes its existence to a fluke of prionlessness:

In 1862, Louis Pasteur boiled broth to kill the microscopic life in it, put some of the liquid in a goose-necked flask, and showed that if nothing living ever reached the liquid, no life would ever grow there. The experiment had enormous practical impact; it gave doctors the knowledge they still use to save lives by showing that because infections were living, reproducing things, if you could keep an environment sterile, you could keep a patient healthy. Had infectious prions been in Pasteur’s flask, curative medicine would never have gotten started. Doctors would still be competing with shamans and medicasters.

Perhaps prion research owes its existence to a similar fluke. Prions are recognizably genetic-infectious-sporadic in a sense untrue of most diseases. But the mainstream take on prion infection is that it’s actually pretty tricky – animal prion research involves injecting the proteins directly into the brain, because anything else won’t work well enough. If we had tried harder to shoot prisoners full of cancer in the 1950s, would it have scooped the recognition of prions? What if Alzheimer’s became a significant research area decades before it did in our world? (Maybe if a 1920s starlet rather than a 1940s one had an early-onset case.) It’s possible prions could never have been recognized as “unique”. We might still be running in circles with scrapie. We might – just might – have had a much bigger problem with BSE.

So goes the Land of Hypotheses. But we don’t live there, not in this life. In this life, we have a thousand unanswered questions. We can’t – yet – simulate all the universes where the prion question went different ways, where Alzheimer’s was a research focus in the 1950s, where we didn’t spend decades chasing the M/M homozygosity illusion, where the first Fore cannibalism victim died of something else, where prions were in Pasteur’s flask. But we can think, and dwell, and dream, and chase possibilities. The Family That Couldn’t Sleep is a great book, precisely because it inspires possibilities. Even the ways it’s become wrong with time are usefully wrong – illustrative, if you will.

“If prion fears go the way of swine flu or Ebola”, indeed.

Fatal familial insomnia is an autosomal dominant disorder. This implies that if the doctor had FFI, his sibling must have also had it, tracing the origin of the gene another generation back – a mutation in one of their parents. The book doesn’t really grapple with this; it seems that whoever the mutation really originated in must’ve died of unrelated causes before developing FFI, which is common in autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorders and makes it a real pain to construct family histories.

I think DTM’s explanation is erroneous. He identifies his disorder as resembling “a form of CMT caused by a mutation on Chromosome 21”, then goes on to describe the specific gene affected. That particular gene is on 8p21, so...understandable game of telephone. There is a reported form of CMT caused by a mutation on 21q22, but it seems to have been first described in 2019.

Despite the rhetorical description of Zigas as an “actual doctor”, quite a few people – including Gajdusek – were sure he was lying about having a medical degree.

They divorced at some point in the 1960s, and Shirley reverted to her maiden name. The book refers to them as “the Glasses” and uses the same surname for both, but most sources write Lindenbaum.

Draw your preferred parallels to modern companies offering polygenic embryo screening.

Realistically, this wasn’t the first case. However, the man in 2009 with vCJD and an M/V genotype wasn’t confirmed at postmortem, so the medical community didn’t accept it until 2016.

Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease is apparently more Alzheimer’s-like, in that DTM says the misdiagnosis is particularly common this way (I get the impression the Vallabh variant is phenotypically most GSS-like, from what I’ve read of Eric and Sonia’s work). GSS is really rare – or really underdescribed, one of those – and it’s hard to find good detailed case descriptions, the kind you’d need to compare it to FFI or CJD on this axis.

Let’s pretend for rhetorical purposes that somewhere like Cheyenne, Wyoming is a meaningful city. The metro area is 100k people – it’s meaningful enough. The equivalent spot in Australia has a population of “no one”.

With the benefit of hindsight, this is known as refeeding syndrome. If someone is deprived of food for long enough, they can’t instantly return to a normal diet. The best-case scenario is that your digestive system is very unhappy with you for a while; the worst case is sudden death.

DTM refers to this as Quality Deer Management, but I think he’s wrong? QDM seems to be a particular attitude towards hunting that avoids shooting young bucks to optimize antler development, while shooting more doe than a pure “kill all the cool-looking ones” strategy will to avoid overpopulation. You can do QDM with or without supplemental feeding. I might be wrong – I know very little about deer hunting