Why AI Safety Won't Make America Lose The Race With China

...

If we worry too much about AI safety, will this make us “lose the race with China”1?

(here “AI safety” means long-term concerns about alignment and hostile superintelligence, as opposed to “AI ethics” concerns like bias or intellectual property.)

Everything has tradeoffs, regulation vs. progress is a common dichotomy, and the more important you think AI will be, the more important it is that the free world get it first. If you believe in superintelligence, the technological singularity, etc, then you think AI is maximally important, and this issue ought to be high on your mind.

But when you look at this concretely, it becomes clear that this is too small to matter - so small that even the sign is uncertain.

The State Of The Race

We can divide the AI race into three levels: compute, models, and applications2. Companies use compute - chips deployed in data centers - to train models like GPT and Claude. Then they use those models in various applications. For now, those applications are things like Internet search and image generation. In the future, they might become geopolitically relevant fields like manufacturing and weapons systems.

Compute: America is far ahead. We have better chips (thanks, NVIDIA) and can produce many more of them (thanks, TSMC). Our recent capex boom, where companies like Google and Microsoft spend hundreds of billions of dollars on data centers, has no Chinese equivalent. By the simplest measure - total FLOPs on each sides - we have 10x as much compute as China, and our advantage is growing every day. A 10x compute advantage corresponds to about a 1-2 year time advantage, or an 0.5 - 1 generation advantage (eg GPT-4 to GPT-5).

Models: The quality of foundation models - giant multi-purpose AIs like GPT or Claude - primarily depends on the amount of compute used to train them, so America’s compute advantage carries over to this level. In theory, clever training methods and advanced algorithms can make one model more or less compute-efficient than another, but this doesn’t seem to be affecting the current state of the race much - most advances by one country are quickly diffused to (or stolen by) the other. Despite some early concerns, neither DeepSeek nor Kimi K2 Chinese models provide strong evidence of a Chinese advantage in computational efficiency (1, 2).

Applications: This is where China is most likely to dominate3. They already outdo America at most forms of advanced manufacturing and infrastructure deployment (eg solar, high-speed rail). And as a command economy, they have more ability to steamroll over concerns like job loss, intellectual property, et cetera.

China knows all of this and is building their AI strategy around it. The plan, which some observers have dubbed “fast follow”, goes like this:

Work hard to catch up with US chip production. They are very far behind here, but also have a long history of catching up to the West on things when they put their mind to it, so they feel up to the challenge. They estimate this will take ten years.

For the next ten years, accept that they may lag somewhat behind America in compute, and therefore on models. But if they can smuggle in chips and steal US technological advances, they can keep this to a manageable 1-2 year gap, rather than a disastrous 4-5 year gap.

Leverage their applications advantage as hard as possible. They imagine that sure, maybe America will have AI that’s 1-2 years more advanced than theirs. But if our smarter AI is still just sitting in a data center answering user queries - and their dumber AI is already integrated with tens of thousands of humanoid robots, automated drones, missile targeting systems, etc - then they still win.

This is a very practical strategy from a very practical country. The Chinese don’t really believe in recursive self-improvement or superintelligence4. If they did, they wouldn’t be so blasé about the possibility of America having AIs 1-2 years more advanced than theirs - if our models pass the superintelligence threshold while theirs are still approaching it, then their advantage in humanoids and drones no longer seems so impressive.

What is the optimal counter-strategy for America? We’re still debating specifics, but a skeletal, obvious-things-only version might be to preserve our compute advantage as long as possible, protect our technological secrets from Chinese espionage, and put up as much of a fight as possible on the application layer.

The State Of AI Safety Policy

It’s worth being specific about what we mean by “AI safety regulation”.

The two most discussed AI safety bills of the past year - California’s SB53 and New York’s RAISE Act - as well as Dean Ball’s proposed federal AI safety preemption bill - all focus on a few key topics:

The biggest companies (eg OpenAI, Anthropic, Google) must disclose their model spec, ie the internal document saying what their models are vs. aren’t banned from doing.

These companies should come up with some kind of safety policy and disclose it.

These companies can’t retaliate against whistleblowers who report violations of their safety policy.

These companies should do some kind of evaluation to see if their AIs can hack critical infrastructure, create biological weapons, or do other mass casualty events.

If they find that the answer is yes, they should tell the government.

If one of these things actually happens during testing, they should definitely tell the government.

These are relatively cheap asks. For example, the evaluation to see whether AIs can hack infrastructure will require hiring people who can conduct the evaluation, allocating compute to the evaluation, etc. But on the scale of an AI training run, the sums involved are tiny. Currently, two nonprofits - METR and Apollo Research - do similar tests on publicly-available models. I estimate their respective budgets at $5 million and $15 million per year. Nonprofits can always pay lower salaries than big companies, so it may cost more for OpenAI to replicate their work - for the sake of argument, $25 million. Meanwhile, the likely cost to train GPT-6 will probably be about $25 - $75 billion, with a b. So the safety testing might increase the total cost by 1/1000th. I asked some people who work in AI labs whether this seemed right; they said that most of the cost would be in complexity, personnel, and delay, and suggested an all-things-considered number ten times higher - 1% of training costs.

But all activists start out with small asks, then move up to larger ones. Is there a risk that the next generation of AI safety regulations will be more burdensome? From what I hear, if we win this round beyond our expectations, the next generation of AI safety asks is third-party safety auditing and location verification for chips. I don’t know the exact details, but these don’t seem order-of-magnitude worse than the current bills. Maybe another 1%.

What about extreme far-future asks? Aren’t there safetyists who want to pause AI progress entirely?

Most people who discuss this want a mutual pause. The most extreme organization in this category, Pause AI, has this on their FAQ:

Q: If we pause, what about China?

A: […] We are primarily asking for an international pause, enforced by a treaty. Such a treaty also needs to be signed by China. If the treaty guarantees that other nations will stop as well, and there are sufficient enforcement mechanisms in place, this should be something that China will want to see as well5.

When we look at concrete AI safety demands, they aren’t of the type or magnitude to affect the race with China very much - maybe 1-2%.

So Is It Impossible For Regulation To Erode The US Lead?

Running the numbers: we started with a 10x compute advantage over China.

Safety legislation risks adding 1-2% to the cost of training runs.

So if we were able to train a model 10x bigger than China’s best model before safety legislation, we can train a model ~9.8x bigger than China’s best model after safety legislation.

Does that mean that America’s chip advantage is so big that no regulation can possibly lose us the race?

Not necessarily. Consider AI ethics regulations like the Colorado AI Act of 2024. It legislates that any institution which uses AI to make decisions (schools, hospitals, businesses, etc) must perform yearly impact assessments evaluating whether the models might engage in “algorithmic discrimination”, a poorly-defined concept from the 2010s that doesn’t really make sense in reference to modern language models. Anyone who could possibly be affected by an AI decision (students, patients, employees, etc) must be notified about the existence of the AI, its inputs and methods, and given an opportunity to appeal any decision which goes against them (for example, if a business used AI when deciding not to hire a job candidate).

In the three-part division that we discussed earlier, the Colorado act most affects the application layer. Instead of imposing a fixed per-training run cost on trillion-dollar companies that don’t care, it places a constant miasma of fear and bureaucracy over small businesses and nonprofits. Some end users might never adopt AI at all. Some startups might be strangled in their infancy. Some niches might end up dominated by one big company with a good legal team that establishes itself as “standard of care” and keeps customers too afraid of regulatory consequences to try anything else. None of this is easy to measure in compute costs, nor does a compute advantage necessarily counterbalance it.

China is relying on this. They know they can’t compete on the compute and model layers in the near-term6, so they’re hoping to win on applications. They imagine America having a slightly better model - GPT-7 instead of GPT-6 - but our GPT-7 is sitting in a data center answering user questions and generating porn, while their GPT-6 is helping to run schools, optimize factories, and pilot drones. America’s task isn’t micro-optimizing our already large compute and model advantages - gunning to bring the score to GPT-7.01 vs. GPT-6. It’s responding to the application-layer challenge that China has set us.

AI safety only tangentially intersects the application layer. There’s no sense in which schools and hospitals need to be doing yearly impact assessments to see whether they have created a hostile superintelligence. Aside from the AI companies themselves, our interest in end users is limited to those who control weapons of mass destruction - biohazard labs, nuclear missile silos, and the like. These institutions should harden themselves against AI attack. All our other asks are concentrated on the model layer, where China isn’t interested in competing and the American position is already strong.

But What If I Really Care About A 1% Model-Layer Gap?

One might argue that every little bit helps. Even though I claim that AI safety regulation only increases training costs by 1%, maybe I’m off by an order of magnitude and it’s 10%, and maybe there will be ten things like that, and when you combine them all then we’re getting to things that might genuinely tip close races. What then?

Here it’s helpful to zoom out and look at the scale of other issues that affect the US-China AI balance, of which the most important is export controls.

America’s biggest advantage in the AI race is our superior chips, which provide the 10x compute advantage mentioned above. Until about 2023, we had few export controls on these. China bought them up and used them to power their own AI industry.

In 2023, the US realized it was in an AI race with China and slashed chip exports. Chinese access to compute dropped dramatically. They began accelerating onshore chip development, but this will take a decade or more to pay off. For now, the Chinese AIs you’ve heard of - DeepSeek, Kimi, etc - are primarily trained on a combination of stockpiled American chips from before the export controls, and American chips smuggled in through third parties, especially Singapore and Malaysia.

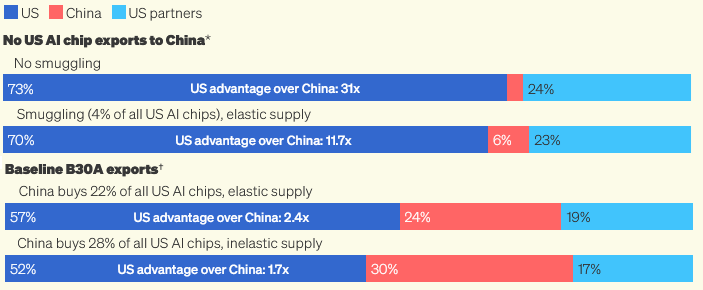

Institute For Progress has a great report analyzing the stakes. They project how much compute each country will add in 2026.

Because our compute advantage keeps growing, we look better in flows than stocks: in a world without smuggling, America adds 31x more compute than China next year. But if China can continue to smuggle at their accustomed rate, the lead collapses from 31x to 10x.

If the US knows about Chinese chip smuggling strategies, why can’t it crack down? The main barriers are a combination of corporate lobbying and poor funding. That is, chip companies want to continue to sell to Singapore and Malaysia without too many awkward questions about where the chips end up. And the Bureau of Industry and Security, the government department charged with countering smuggling, gets about $50 million/year to spend on chips, which experts say is not enough to plug all the holes. To put that number in context, Mark Zuckerberg recently made job offers as high as $1 billion per AI researcher. If America cared about winning the race against China even a tenth as much as Mark Zuckerberg cares about winning the race against OpenAI, we would be in a much better position!

It gets worse. NVIDIA, America’s biggest company, constantly lobbies to be allowed to sell its advanced chips to China. It’s not afraid to play dirty, and stands accused of trying to get China hawks pushed out of government for resisting; Steven Adler reports “widespread fear among think tank researchers and policy experts who publish work against NVIDIA’s interests”. Foundation for American Innovation fellow David Cowan goes further, saying that “NVIDIA is a national security risk”.

All of this lobbying has paid off: the administration keeps proposing changing the rules to allow direct chip sales to China. So far cooler heads have prevailed each time, but the deal keeps popping back onto the table. NVIDIA tries to argue that the models being proposed for export are only second-rate chips that won’t affect the compute balance, but this is false - last month’s talks involved the most price-performant chip on the market. Here’s IFP’s calculation for how caving on this issue would affect the AI race:

It would decrease our compute advantage from 10-30x to about 2x. You can read the report for more scenarios, including one where aggressive chip exports actually give China a compute advantage.

Commentators have struggled to describe how bad an idea this is. Some say it would be like selling Russia our nukes during the Cold War, or selling them our Saturn V rockets during the space race. The problem isn’t just that Russia gets free rockets. It’s also that every rocket we sell to Russia is one that we can’t use ourselves. We’re crippling our own capacity in order to enrich our rivals.

Yet some of the loudest voices warning against AI safety regulation on “race with China” grounds support NVIDIA chip exports! For example, White House “AI and crypto czar” David Sacks, a strident opponent of AI safety regulation, has been instrumental in trying to dismantle export controls and anti-smuggling efforts. According to NYT:

Mr. Sacks disliked another Biden administration rule that controlled A.I. chip sales around the world. He also questioned Washington’s consensus that selling A.I. chips abroad would be bad for the United States.

Some people argue that giving China our chips prevents them from learning to make their own. I think this is historically naive: has giving China our advanced technology ever worked before? “Maybe letting China access our technology will open up new markets for American goods” is the “maybe the stripper really likes you” of international trade. We have tried this for decades; every time, China has stolen the tech and made their own, better versions. China is obsessed with autarky - the idea that after a “century of humiliations”, they shouldn’t depend industrially on any outside power. They aren’t going to give up on chip manufacturing, a vital dual-use technology. We shouldn’t blow our entire present-day AI lead in the hopes that China will do the thing which it has never done once in history and which its entire industrial culture is centered around not doing. If we give them chips, they’ll both use our chips and develop their own (remember, China is a command economy, and they don’t have to stop developing their own chips just because there’s a lower-cost option). Then they’ll use their AIs, built with our chips, to compete with American AIs on the international market.

Others argue that chip sanctions just encourage China to be smarter and more compute-efficient, and that we’ll regret training them into a scrappy battle-hardened colossus. I think this is insulting to American and Chinese researchers, who are already working maximally hard to discover efficiency improvements regardless of our relative compute standing. More important, it doesn’t seem to be true - Chinese AIs are no more compute-efficient than American models, with most claims to the contrary being failures of chip accounting. I’m not even sure the people making this argument believe their own claims. When I play devil’s advocate and ask them whether America should perhaps pass lots of AI safety regulations a hundred times stricter than the ones actually under consideration - since that would increase training costs, reduce the number of chips we can afford, and cripple us in the same way that chip sanctions cripple China - these people suddenly forget about their bad-things-are-good argument and go back to believing that bad things are bad again.

A final argument for chip exports: right now, chip autarky is something like China’s number five national priority. But if our AI lead becomes too great, they might increase it to number one, and catch up quicker. If we allow some chip exports to China, we can keep our lead modest, and prevent them from panicking and working even harder to catch up. This is too 4D chess for me - we have to keep our lead small now so it can be bigger later? But again, if you support keeping our lead small to avoid scaring China, you can’t turn around and say you’re against AI safety regulation because it might shrink our lead!

Absent galaxy-brained takes like these, reducing our 30x compute advantage relative to China to a 1.7x compute advantage is extremely bad - orders of magnitude worse than any safety regulation. So why do so many of the same people who panic over AI safety regulation - who call us “traitors” for even considering it- completely fail to talk about the export situation at all, or engage with it in dumb and superficial ways?

I don’t think this combination of positions comes from a sober analysis of the AI race. I think people have narratives they want to tell about government, regulation and safetyism, and the AI safety movement - which has “safety” right in the name! - makes a convenient villain. The topics that really matter, like export controls, don’t lend themselves to these stories equally well - you would have to support something with “controls” right in the name!7 - so they get pushed to the sideline.

But the people who care most about the race against China are focusing most of their energy on export controls, some energy on application-layer regulations like the one in Colorado, and barely think about AI safety at all.

It’s Too Early To Even Know The Sign Of AI Safety Regulations

Narratives about regulation stifling progress are attractive because they are often true. A time may come when the Overton Window shifts to a set of AI safety regulations strong enough to substantially slow American AI. Perhaps this will happen at the same time that China finally solves its own chip shortage - likely sometime in the 2030s - and America can no longer rely on its compute advantage for breathing room. Then the threat of Chinese ascendancy will be a relevant response to concerns about safety. Perhaps people raising these arguments now believe that they are protecting themselves against that future - better to cut the safety movement out at its root, before it starts to really matter. Be that as it may, their public communications present the case that AI safety regulation is already a big threat. This is false, and should be called out as such.

But also, it’s based on a flawed idea that the only way AI safety can affect the race with China is to slow us down. I’ve already argued that the magnitude of any deceleration is trivial. But I’ll go further and say it’s too early even to know what the sign of AI safety regulations is; whether they might actually speed us up relative to China.

First, safety-inspired regulation is leading the way in keeping data centers secure. Secure data centers prevent hostile AIs from hacking their way out, but they also prevent Chinese spies from hacking their way in. The safety-inspired SB 53 is the strictest AI cybersecurity regulation on the books, demanding that companies report “cybersecurity practices and how the large developer secures unreleased model weights from unauthorized modification or transfer by internal or external parties.” So far, no other political actor has been equally interested in the types of measures that would prevent the Chinese from stealing US secrets and model weights; this is a key factor in developing a model-layer lead.

Second, safetyists are pushing for compute governance: tags on chips that let governments track their location and use. This would be a key technology for monitoring any future international pause, but incidentally would also make it much easier to end smuggling and prevent the slow trickle of American chips to Chinese companies.

Third, China is having its own debate over whether it can prioritize safety without losing the race against America! See for example TIME - China Is Taking AI Safety Seriously. So Must The US. If America signals that it takes safety seriously, this might give pro-safety Chinese factions more room to operate on their side of the ocean, leaving both countries better off.

Finally, small regulations now could prevent bigger regulations later. In the wake of a catastrophe, governments over-react. If something went wrong with AI - even something very small, like a buggy AI inserting deliberate malware into code that brought down a few websites, or a terrorist group using an AI-assisted bioweapon to make a handful of people sick - the resulting panic could affect the AI industry the same way 9/11 affected aviation. If safety regulations halve the likelihood of a near-term catastrophe at the cost of adding 1% to training runs, it’s probably worth it.

More generally, industry leaders tend to play up how much they want to win the race with China when it’s convenient for them - for example, as a way of avoiding regulation - then turn around and sell China our top technology when it serves their bottom line. Safetyists may have some other priorities layered on top, but we actually want to win the race with China, because a full appreciation of the potential of superintelligence produces a natural reluctance to let it fall into the hands of dictators. A recent Washington Examiner article pointed to “effective altruists” in DC as responsible for some of the strongest bills aimed at preserving American AI supremacy, both during the last administration and the current one.

When the wind changes, and the position of industry leaders changes with it, you may be glad to have us around.

For purposes of this post, I am accepting the race framework as a given; for challenges to it, see eg here.

This section comes mostly from personal conversations, but is pretty similar to the conclusions of Nathan Barnard and Dean Ball.

Especially in hardware applications. The US has a good software ecosystem, and more advanced models might let us keep an edge in AI-enabled software applications like Cursor.

With the notable exception of Liang Wenfeng, CEO of DeepSeek. This is maybe not so different from the US, where tech company CEOs believe in superintelligence while the government tends towards more practical near-term thinking. But in America, companies are more influential relative to government than in China. In particular, DeepSeek is much poorer than the American tech giants and has little access to VC funding. So where the US tech giants can engage in massive data center buildup on their own, a similar capex push in China will need to be led by the government.

It’s more complicated than this, because the US is in a stage of the race where it’s mostly working on building AIs, and China is in a stage of the race where it’s mostly working on developing chips. If a treaty bans both sides from building AI, China can still develop its chips, and be in a better place vis-a-vis the United States when the treaty ends than when it began. A truly fair treaty would have to either wait until China had finished developing its chips and was also in the building-AI stage of the race (5-10 years), or place restrictions on Chinese chip development, or otherwise compensate the US for this asymmetry.

It will take until about 2035 for China to be able to seriously compete on compute. After that, they most likely end up with a large compute advantage due to their superior manufacturing base, energy infrastructure, state capacity, and lack of NVIDIA profit margins (see footnote 7 below). If America doesn’t have superintelligence by then, we are in trouble. I don’t know of anyone who has a great plan for this besides trying to improve on all these fronts, and I also don’t have a great plan for this.

Future developments may threaten these people’s China hawkery even further. NVIDIA has a 90% profit margin on every advanced chip sold in the US. China is still working on developing advanced chips, but once they get them, the government will make Huawei sell at minimal profit margins, to support the national interest of winning the AI race. That means that at technological parity, US chips will cost 10x Chinese chips, and it may become a live topic of debate whether the US government should force NVIDIA to cut its own profit margins. I can only vaguely predict who will take which side of these debate, but I bet it won’t line up with current levels of China hawkery.