The Good News Is That One Side Has Definitively Won The Missing Heritability Debate

...

…the bad news is that they can’t agree which one.

I explained the debate more here, but the short version is: twin studies find that most traits are at least 50% genetic, sometimes much more. But molecular studies - that is, attempts to find the precise genes responsible - usually only found enough genes for the traits to be ~10-20% genetic. The remaining 35% was dubbed “missing heritability”. Nurturists argued that the twin studies must be wrong; hereditarians argued that missing effect must be in hard-to-find genes.

The latter seemed plausible because typical genetic studies only investigate the genes that most commonly vary across people - about 0.1% of the genome. Maybe the other 99.9% of genes, even though they rarely vary across people, are so numerous that even their tiny individual effects could add up to a large overall influence. There was no way to be sure, because variation in these genes was too rare to study effectively.

But as technology improved, funding increased, and questions about heredity became more pressing, geneticists finally set out to do the hard thing. They gathered full genomes - not just the 0.1% - from thousands of people, and applied a whole-genome analysis technique called GREML-WGS. The resulting study was published earlier this month as Estimation and mapping of the missing heritability of human phenotypes, by Wainschtein, Yengo, et al.

Partisans on both sides agree it’s finally resolved the missing heritability debate, but they can’t agree on what the resolution is.

First, the study. The researchers got genetic data from 347,630 British people, and also measured their level of 34 traits, including both biomedical traits (like white blood cell count) and socially-relevant behavioral traits (like IQ).

Resolving missing heritability requires matching twin studies to genetic studies. The researchers were well-prepared to do a genetic study. But they couldn’t do a twin study, because most people in their sample did not have twins. And they couldn’t rely on the results of other twin studies, because twin studies - like every other type of study - return slightly different results in each group of people. So instead, they performed a “pedigree” study (their term, although it’s somewhat different from how pedigree studies usually work). Close relatives share whole chromosomes or other large stretches of DNA. By looking at who shared how many of these, they created a genealogical map of their sample: who was brothers, sisters, first cousins, second cousins, etc. Since there were 300,000+ participants, this was easy. Then, across moderately close relatives, they compared trait similarity to degree of relation. For example, I might be very similar in IQ to my brother, but somewhat less similar to my cousin, and even less similar to my second cousin once removed. After doing all of this, they could figure out how much more similar relatives were than non-relatives and get a family-based estimate for how genetic different traits were. This was their stand-in for twin studies.

Then they switched to people who were not close relatives, and tried to calculate their trait similarity based on detected genetic similarity; essentially, how many genes we share by pure chance. That is, if I and my neighbor are 50.001% genetically similar, and I and my other neighbor are 49.999% genetically similar, how much more do I resemble my first neighbor than my second neighbor?

When they were done, their pedigree study gave them a stand-in for twin studies, and their genetic study gave them an estimate of how much heritability could be detected with molecular genetic studies using both rare and common genes. This let them compare the two numbers, assessing the size of the “heritability gap” inclusive of rare variants.

The headline result: “WGS captures approximately 88% of the pedigree-based narrow sense heritability.”

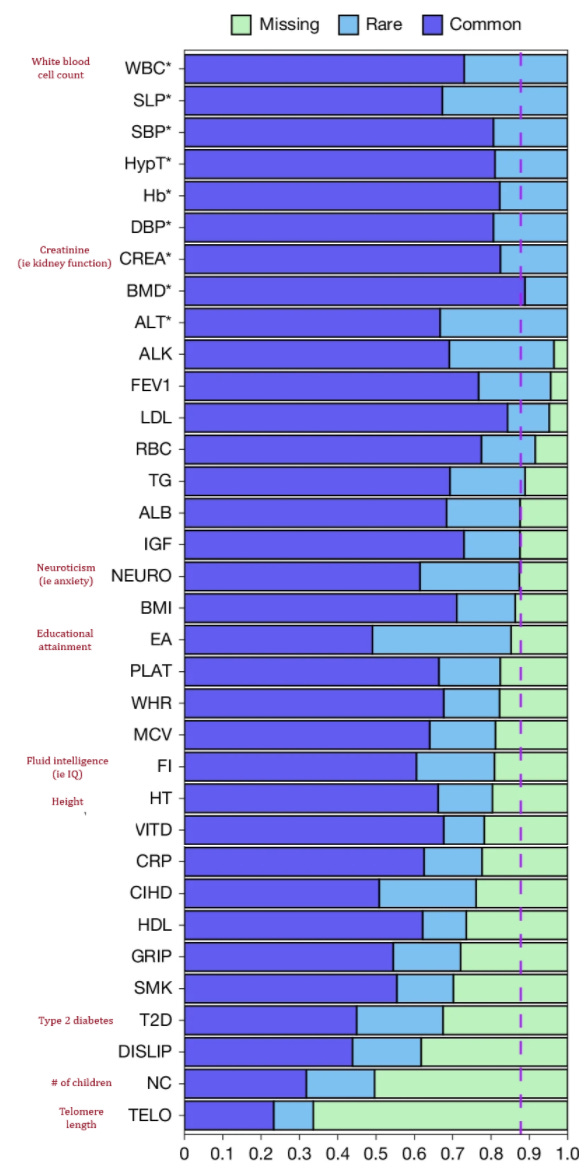

The hereditarians declared victory (Cremieux on X, Emil Kirkegaard on Substack) because of this graph:

That is, once you include the rare variants, the amount of genetic variation that “should” exist but doesn’t shrinks to only 12%. Plausibly an even bigger study, investigating even rarer variants, could shrink the gap further, all the way to zero. The oldest and strongest argument against hereditarianism - if all these genes exist, why can’t we find them? - has finally been put to rest. You couldn’t find them because they were rare. But when you include rare variants in your search, you can find at least 88% of them.

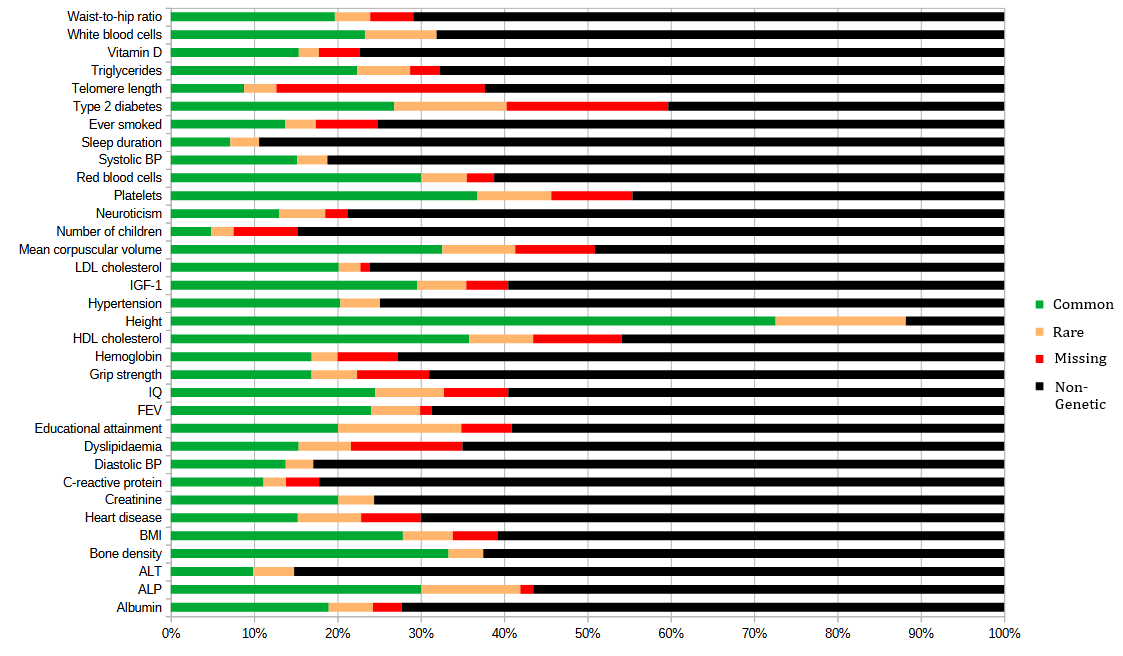

But the nurturists declared victory (Sasha Gusev on Substack) because the graph, zoomed out, looks like this:

Of the colored region, very little is red (representing missing heritability). But most of the graph is still black - ie, not heritable. So for example, this study found that IQ was 41% heritable, and they were able to “find” 33%pp of that - a full three-quarters. But 41% heritable is still a low number!

Previous studies found high numbers (like 50 - 80%) for expected heritability, but were only able to get small numbers (10 - 20%pp) for “found heritability”. This study “closed the gap” by finding medium numbers (~30 - 40%) for both. But a medium amount of almost-fully-found heritability is still only a medium amount of heritability. Start with 30 - 40%, shave off a bit for confounders, and you might end up with only 10 - 20% direct causal heritability, which would be a total nurturist victory.

The hereditarians object that this study wasn’t designed to pinpoint specific heritability numbers. Other methods are more accurate. But (the nurturists counter) those more accurate methods disagree among themselves, and some of them give results similar to the low numbers in this study. So this study is welcome (to nurturists) confirmation that the other low studies might have been on the right track.

In other words, your interpretation on this study depends on which of these statements you agree with more:

This study was designed to determine whether the missing heritability - the gap between relatedness and molecular methods - can be found in rare variants. It can be. We should celebrate this, and not worry too much about the exact heritability numbers, since it was never designed to find exact numbers in the first place.

This study determined that there was never that much heritability to find in the first place. We found that small amount, but it’s still small. This study wasn’t designed to pinpoint exact numbers, but the ones that are all also sort of consistent with it being small, and this study certainly doesn’t provide any extra evidence that it isn’t.

So who’s right?

Emil and Cremieux argue that we know why this study found low heritability of IQ. It’s because you can’t give 347,630 people a full-length IQ test. So they gave these people a short crappy IQ-like test with a lot of random noise. Past studies estimated the reliability of this test at 0.61 (low). It’s easy to statistically correct for this; when you do so, you find that if the test had been better, this study would have estimated the heritability of IQ at 55%. This is still on the low end, but it’s already within the hereditarians’ estimate of 50 - 80%, and there are a few other biases that might be bringing it down too (eg healthy volunteer bias).

The advantage of this theory is that the measurements and statistical corrections are pretty simple, and it’s definitely true. The disadvantage is that IQ is only one piece of this bigger puzzle, and every trait in the study is lower than expected.

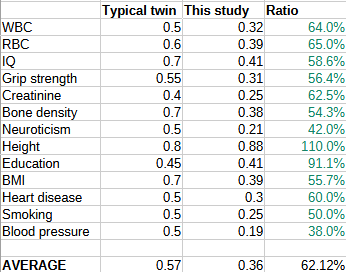

This table compares the heritability found in a typical twin study to the heritability numbers found in the pedigree portion of this study. On average, this study’s numbers are only about 60% as high; IQ isn’t really an outlier (although if we used Kirkegaard’s adjusted number, that wouldn’t be too much of an outlier either).

But this same argument can be deployed against the nurturists’ favorite explanations for high twin study numbers: population stratification and assortative mating. These could be expected to affect socially-relevant and environmentally-mediated traits like educational attainment. But nobody assortative-mates on white blood cell count, and these types of “hard” biomedical traits are just as depressed in this study as the “soft” behavioral ones.

The real answer is that despite everyone’s pronouncements, nobody’s won, nothing has been resolved, and the debate continues. Different studies continue to find different heritability estimates and nobody has a good explanation why. Here are the two stories you could tell, updated for this new paper:

Hereditarian: Most traits are 50 - 80% heritable, as per twin studies, adoption studies, and classic pedigree studies. Molecular genetics studies underestimate this because much of the heritability is in rare variants, as this new study demonstrates. Sib-regression, RDR, and this new study’s “pedigree-style” analysis underestimate this because they’re untested methods applied to problematic samples and the estimates are noisy; also, shut up.

Nurturist: Most traits are ~30% heritable, as per Sib-regression, RDR, molecular genetics, and this new study’s “pedigree-style” analysis. Twin studies, adoption studies, and pedigree studies overestimate this because of assortative mating and population stratification. This affects biomedical traits like white blood cell count just as much as behavioral traits, because shut up. The one sib-regression study that found very high heritability for IQ was just a weird sample, or noise.

Can we reconcile these narratives?

The hereditarian case is strongest for height, but only slightly weaker for intelligence. If we accept Kirkegaard and Cremieux’s correction, then this study found up to 55% heritability of IQ, and the only sib-regression study on the topic found 75% (albeit with low confidence). But this is stringing together a corrected estimate with a noisy estimate and I have low confidence that the next study won’t find something lower.

The nurturist case is strongest for educational attainment. This is easily confused by nondirect effects, and a sib-regression study, the best type to see through the confusion, found <10% direct heritability. But if IQ is >55% heritable and educational attainment is <10% heritable, does this require us to believe that IQ only barely affects success in education? A certain sort of contrarian might relish this conclusion.

The biomedical traits confuse me the most; it’s still hard to square the twin studies with the sib-regression and molecular estimates. Either people are somehow assortative mating on blood pressure, or else these remain the strongest evidence of some deeper problem.