The Dilbert Afterlife

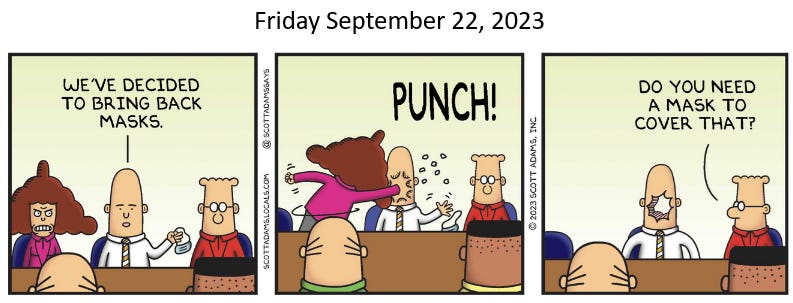

Sixty-eight years of highly defective people

Thanks to everyone who sent in condolences on my recent death from prostate cancer at age 68, but that was Scott Adams. I (Scott Alexander) am still alive1.

Still, the condolences are appreciated. Scott Adams was a surprisingly big part of my life. I may be the only person to have read every Dilbert book before graduating elementary school. For some reason, 10-year-old-Scott found Adams’ stories of time-wasting meetings and pointy-haired bosses hilarious. No doubt some of the attraction came from a more-than-passing resemblance between Dilbert’s nameless corporation and the California public school system. We’re all inmates in prisons with different names.

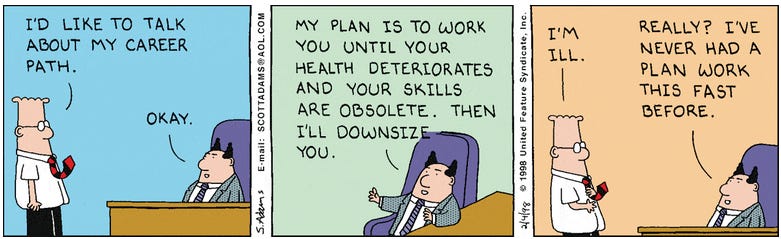

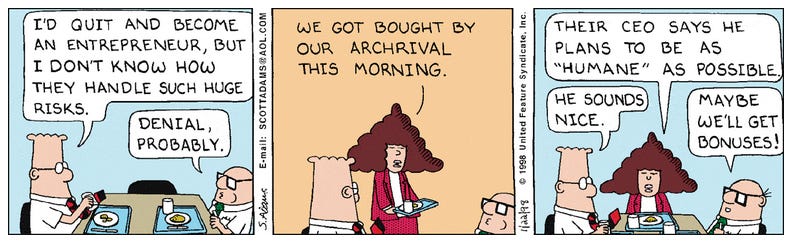

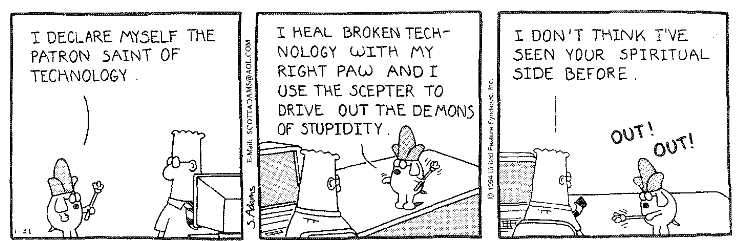

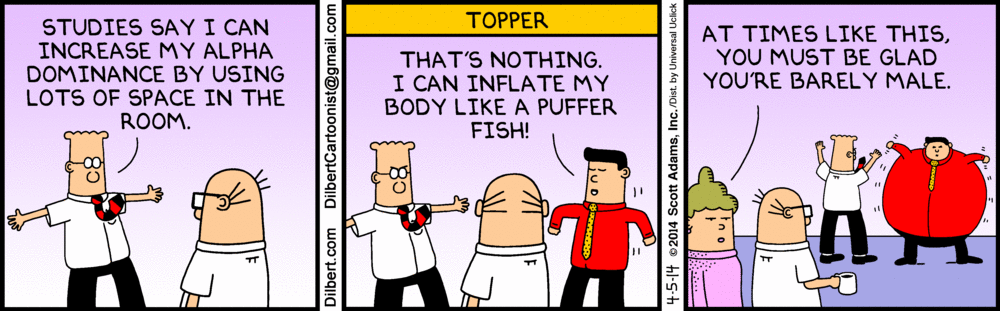

But it would be insufficiently ambitious to stop there. Adams’ comics were about the nerd experience. About being cleverer than everyone else, not just in the sense of being high IQ, but in the sense of being the only sane man in a crazy world where everyone else spends their days listening to overpaid consultants drone on about mission statements instead of doing anything useful. There’s an arc in Dilbert where the boss disappears for a few weeks and the engineers get to manage their own time. Productivity shoots up. Morale soars. They invent warp drives and time machines. Then the boss returns, and they’re back to being chronically behind schedule and over budget. This is the nerd outlook in a nutshell: if I ran the circus, there’d be some changes around here.

Yet the other half of the nerd experience is: for some reason this never works. Dilbert and his brilliant co-workers are stuck watching from their cubicles while their idiot boss racks in bonuses and accolades. If humor, like religion, is an opiate of the masses, then Adams is masterfully unsubtle about what type of wound his art is trying to numb.

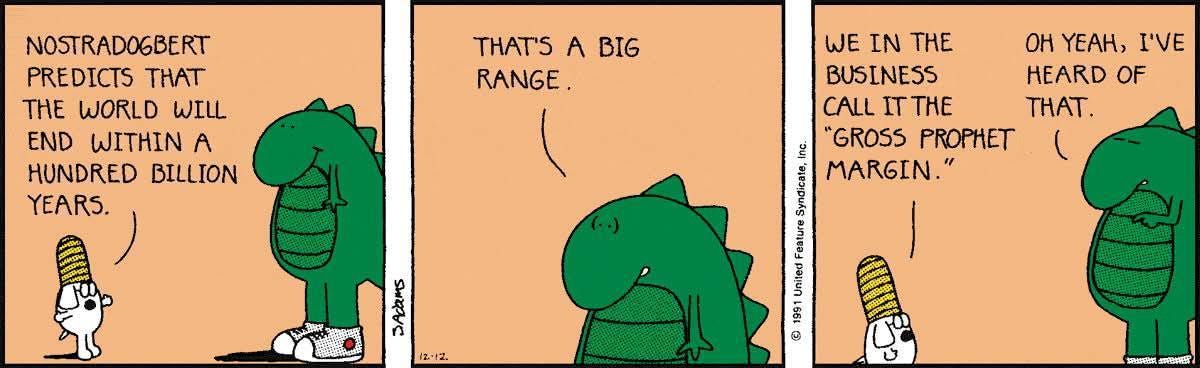

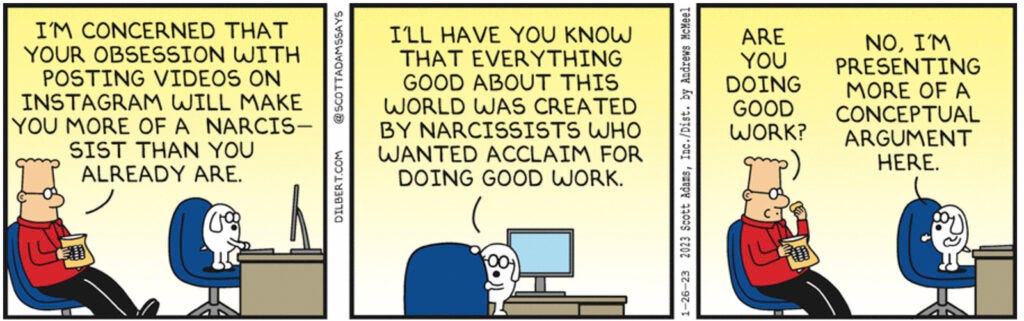

This is the basic engine of Dilbert: everyone is rewarded in exact inverse proportion to their virtue. Dilbert and Alice are brilliant and hard-working, so they get crumbs. Wally is brilliant but lazy, so he at least enjoys a fool’s paradise of endless coffee and donuts while his co-workers clean up his messes. The P.H.B. is neither smart nor industrious, so he is forever on top, reaping the rewards of everyone else’s toil. Dogbert, an inveterate scammer with a passing resemblance to various trickster deities, makes out best of all.

The repressed object at the bottom of the nerd subconscious, the thing too scary to view except through humor, is that you’re smarter than everyone else, but for some reason it isn’t working. Somehow all that stuff about small talk and sportsball and drinking makes them stronger than you. No equation can tell you why. Your best-laid plans turn to dust at a single glint of Chad’s perfectly-white teeth.

Lesser lights may distance themselves from their art, but Adams radiated contempt for such surrender. He lived his whole life as a series of Dilbert strips. Gather them into one of his signature compendia, and the title would be Dilbert Achieves Self Awareness And Realizes That If He’s So Smart Then He Ought To Be Able To Become The Pointy-Haired Boss, Devotes His Whole Life To This Effort, Achieves About 50% Success, Ends Up In An Uncanny Valley Where He Has Neither The Virtues Of The Honest Engineer Nor Truly Those Of The Slick Consultant, Then Dies Of Cancer Right When His Character Arc Starts To Get Interesting.

If your reaction is “I would absolutely buy that book”, then keep reading, but expect some detours.

Fugitive From The Cubicle Police

The niche that became Dilbert opened when Garfield first said “I hate Mondays”. The quote became a popular sensation, inspiring t-shirts, coffee mugs, and even a hit single. But (as I’m hardly the first to point out) why should Garfield hate Mondays? He’s a cat! He doesn’t have to work!

In the 80s and 90s, saying that you hated your job was considered the height of humor. Drew Carey: “Oh, you hate your job? There’s a support group for that. It’s called everybody, and they meet at the bar.”

This was merely the career subregion of the supercontinent of Boomer self-deprecating jokes, whose other prominences included “I overeat”, “My marriage is on the rocks”, “I have an alcohol problem”, and “My mental health is poor”.

Arguably this had something to do with the Bohemian turn, the reaction against the forced cheer of the 1950s middle-class establishment of company men who gave their all to faceless corporations and then dropped dead of heart attacks at 60. You could be that guy, proudly boasting to your date about how you traded your second-to-last patent artery to complete a spreadsheet that raised shareholder value 14%. Or you could be the guy who says “Oh yeah, I have a day job working for the Man, but fuck the rat race, my true passion is white water rafting”. When your father came home every day looking haggard and worn out but still praising his boss because “you’ve got to respect the company or they won’t take care of you”, being able to say “I hate Mondays” must have felt liberating, like the mantra of a free man2.

This was the world of Dilbert’s rise. You’d put a Dilbert comic on your cubicle wall, and feel like you’d gotten away with something. If you were really clever, you’d put the Dilbert comic where Dilbert gets in trouble for putting a comic on his cubicle wall on your cubicle wall, and dare them to move against you.

(again, I was ten at the time. I only know about this because Scott Adams would start each of his book collections with an essay, and sometimes he would talk about letters he got from fans, and many of them would have stories like these.)

But t-shirts saying “Working Hard . . . Or Hardly Working?” no longer hit as hard as they once did. Contra the usual story, Millennials are too earnest to tolerate the pleasant contradiction of saying they hate their job and then going in every day with a smile. They either have to genuinely hate their job - become some kind of dirtbag communist labor activist - or at least pretend to love it. The worm turns, all that is cringe becomes based once more and vice versa. Imagine that guy boasting to his date again. One says: “Oh yeah, I grudgingly clock in every day to give my eight hours to the rat race, but trust me, I’m secretly hating myself the whole time”? The other: “I work for a boutique solar energy startup that’s ending climate change - saving the environment is my passion!” Zoomers are worse still: not even the fig leaf of social good, just pure hustle.

Silicon Valley, where hustle culture has reached its apogee, has an additional consideration: why don’t you found a startup? If you’re so much smarter than your boss, why not compete against him directly? Scott Adams based Dilbert on his career at Pacific Bell in the 80s. Can you imagine quitting Pacific Bell in the 80s to, uh, found your own Pacific Bell? To go to Michael Milken or whoever was investing back then, and say “Excuse me, may I have $10 billion to create my own version of Pacific Bell, only better?” But if someone were to try to be Dilbert today – to say, earnestly, “I hate my job because I am smarter than my boss and could do it better than him,” that would be the obvious next question, the same way “I am better at picking stocks than Wall Street” ought to be followed up with “Then why don’t you invest?”

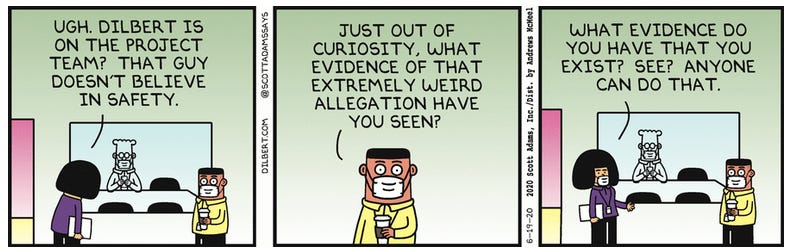

Above, I described “the nerd experience” of “being smarter than everyone else, not just in the sense of being high IQ, but in the sense of being the only sane man in a crazy world where everyone else spends their days listening to overpaid consultants drone on about mission statements instead of doing anything useful.” You nodded along, because you knew the only possible conclusion to the arc suggested by that sentence was to tear it down, to launch a tirade about how that nerd is naive and narcissistic and probably somehow also a racist. In the year of our Lord 2026, of course that’s where I’m going.

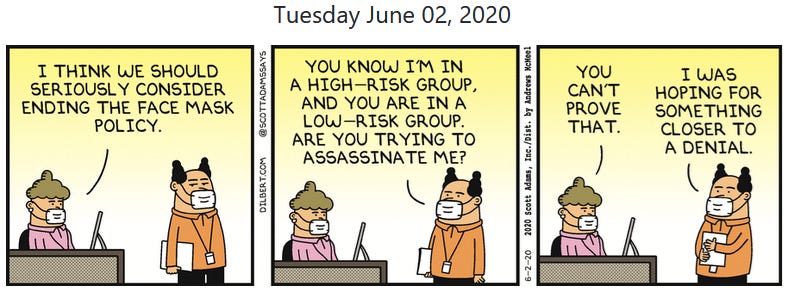

Dilbert is a relic of a simpler time, when the trope could be played straight. But it’s also an artifact of the transition, maybe even a driver of it. Scott Adams appreciated these considerations earlier and more acutely than anyone else. And they drove him nuts.

Stick To Drawing Comics, Monkey Brain

Adams knew, deep in his bones, that he was cleverer than other people. God always punishes this impulse, especially in nerds. His usual strategy is straightforward enough: let them reach the advanced physics classes, where there will always be someone smarter than them, then beat them on the head with their own intellectual inferiority so many times that they cry uncle and admit they’re nothing special.

For Adams, God took a more creative and – dare I say, crueler – route. He created him only-slightly-above-average at everything except for a world-historical, Mozart-tier, absolutely Leonardo-level skill at making silly comics about hating work.

Scott Adams never forgave this. Too self-aware to deny it, too narcissistic to accept it, he spent his life searching for a loophole. You can read his frustration in his book titles: How To Fail At Almost Everything And Still Win Big. Trapped In A Dilbert World. Stick To Drawing Comics, Monkey Brain. Still, he refused to stick to comics. For a moment in the late-90s, with books like The Dilbert Principle and The Dilbert Future, he seemed on his way to be becoming a semi-serious business intellectual. He never quite made it, maybe because the Dilbert Principle wasn’t really what managers and consultants wanted to hear:

I wrote The Dilbert Principle around the concept that in many cases the least competent, least smart people are promoted, simply because they’re the ones you don't want doing actual work. You want them ordering the doughnuts and yelling at people for not doing their assignments—you know, the easy work. Your heart surgeons and your computer programmers—your smart people—aren't in management.

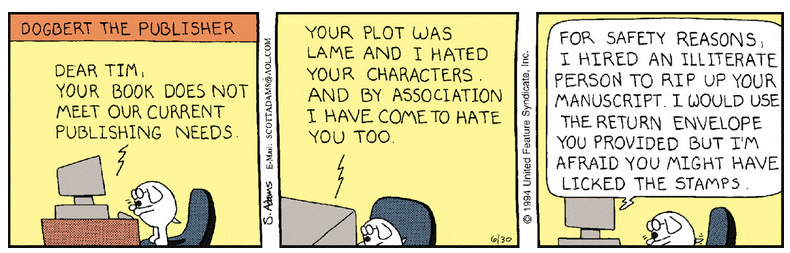

Okay, “I am cleverer than everyone else”, got it. His next venture (c. 1999) was the Dilberito, an attempt to revolutionize food via a Dilbert-themed burrito with the full Recommended Daily Allowance of twenty-three vitamins. I swear I am not making this up. A contemporaneous NYT review said it “could have been designed only by a food technologist or by someone who eats lunch without much thought to taste”. The Onion, in its twenty year retrospective for the doomed comestible, called it a frustrated groping towards meal replacements like Soylent or Huel, long before the existence of a culture nerdy enough to support them. Adams himself, looking back from several years’ distance, was even more scathing: “the mineral fortification was hard to disguise, and because of the veggie and legume content, three bites of the Dilberito made you fart so hard your intestines formed a tail.”

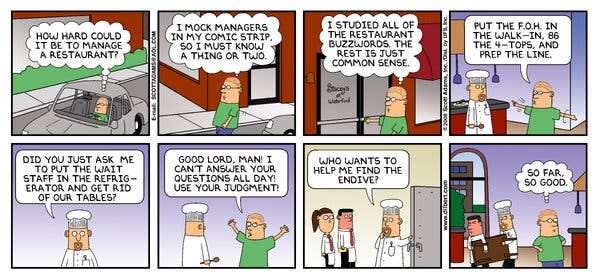

His second foray into the culinary world was a local restaurant called Stacey’s. The New York Times does a pitch-perfect job covering the results. Their article starts:

This is yet another story about a clueless but obtrusive boss — the kind of meddlesome manager you might laugh at in the panels of “Dilbert,” the daily comic strip.

…and continues through a description of Adams making every possible rookie mistake. As the restaurant does worse and worse, Adams becomes more and more convinced that he has to figure out some clever lifehack that will turn things around and revolutionize restaurants. First he comes up with a theory that light is the key to restauranting, and spends ages fiddling with the windows. When this fails, he devolves into an unmistakable sign of desperation - asking blog commenters for advice:

He also turned to Dilbert fans for suggestions on how to use the party room, in a posting on his blog titled “Oh Great Blog Brain.” The Dilbert faithful responded with more than 1,300 comments, mixing interesting ideas (interactive murder-mystery theater) with unlikely mischief (nude volleyball tournaments). Mr. Adams asked his employees to read the comments and is now slowly trying some of them.

But what makes this article truly perfect - I can’t believe it didn’t get a Pulitzer - is that it’s not some kind of hostile ambush profile. Adams is totally self-aware. He also finds the whole situation hilarious! Everyone involved is in on the joke! The waiters find it hilarious! After every workday, Adams and the waiters get together and laugh long into the night together about how bad a boss Adams is!

There’s a running joke about how if you see a business that loses millions yearly, it’s probably run by some banker’s wife who’s getting subsidized to feel good about herself and pretend she has a high-powered job. I think this is approximately what was going on with Stacey’s. Adams made enough money off Dilbert that he could indulge his fantasies of being something more than “the Dilbert guy”. For a moment, he could think of himself as a temporarily-embarrassed businessman, rather than just a fantastically successful humorist. The same probably explains his forays into television (“Dilbert: The Animated Series”), non-Dilbert comics (“Plop: The Hairless Elbonian”), and technology (”WhenHub”, his site offering “live chats with subject-matter experts”, which was shelved after he awkwardly tried to build publicity by suggesting that mass shooting witnesses could profit by using his site to tell their stories.)

Adams and Elon Musk occasionally talked about each other - usually to defend one another against media criticism of their respective racist rants - but I don’t know if they ever met. I wonder what it would have been like if they did. I imagine them coming together at some Bay Area house party on copious amounts of LSD or MDMA. One, the world’s greatest comic writer, who more than anything else wanted to succeed in business. The other, the world’s greatest businessman, who more than anything else wanted people to think that he’s funny. Scott Adams couldn’t stop frittering his talent and fortune on doomed attempts to be taken seriously. But someday Elon Musk will buy America for $100 trillion, tell the UN that he’s renaming it “the United States of 420-69”, and the assembled ambassadors will be as silent as the grave. Are there psychic gains from trade to be had between two such people?

Michael Jordan was the world’s best basketball player, and insisted on testing himself against baseball, where he failed. Herbert Hoover was one of the world’s best businessmen, and insisted on testing himself against politics, where he crashed and burned. We’re all inmates in prisons of different names. Most of us accept it and get on with our lives. Adams couldn’t stop rattling the bars.

I’m No Scientist, But I Think Feng Shui Is Part Of The Answer

Having failed his forays into business, Adams turned to religion. Not in the sense of seeking consolation through God’s love. In the sense of trying to show how clever he was by figuring out the true nature of the Divine

The result was God’s Debris. This is not a good book. On some level, Adams (of course) seemed to realize this, but (of course) his self-awareness only made things worse. In the second-worst introduction to a work of spiritual wisdom I’ve ever read (Gurdjieff keeps first place by a hair), he explains that this is JUST A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT and IF YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY, YOU FAIL. But also, it really makes you think, and it’s going to blow your mind, and you’ll spend the rest of your life secretly wondering whether it was true, but it won’t be, because IT’S JUST A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT, and IF YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY, YOU FAIL. Later, in a Bloomberg interview, he would say that this book - and not Dilbert - would be his “ultimate legacy” to the world. But remember, IT’S JUST A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT, and IF YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY YOU FAIL.

I read it for the first time while researching this essay. The frame story is that a delivery boy gives a package to the wisest man in the universe, who invites him to stay a while and discuss philosophy (REMEMBER, IT’S JUST A WORK OF FICTION! THESE ARE ONLY CHARACTERS!) Their discussion is one-quarter classic philosophical problems that seemed deep when you were nineteen, presented with no reference to any previous work:

“There has to be a God,” I said. “Otherwise, none of us would be here.” It wasn’t much of a reason, but I figured he didn’t need more.

“Do you believe God is omnipotent and that people have free will?” he asked.

“That’s standard stuff for God. So, yeah.”

“If God is omnipotent, wouldn’t he know the future?”

“Sure.”

“If God knows what the future holds, then all our choices are already made, aren’t they? Free will must be an illusion.”

He was clever, but I wasn’t going to fall for that trap. “God lets us determine the future ourselves, using our free will,” I explained.

“Then you believe God doesn’t know the future?”

“I guess not,” I admitted. “But he must prefer not knowing.”

There is an ongoing meta-discussion among philosophy discussers of how acceptable it is to propose your own answers to the great questions without having fully mastered previous scholarship. On the one hand, philosophy is one of the most fundamental human activities, gating it behind the near-impossible task of having read every previous philosopher is elitist and gives self-appointed guardians of scholarship a permanent heckler’s veto on any new ideas, and it can create a culture so obsessed with citing every possible influence that eventually the part where you have an opinion withers away and philosophy becomes a meaningless ritual of presenting citations without conclusion. On the other hand, this book.

Another quarter is philosophical questions which did not seem deep, even when you were nineteen, and which nobody has ever done work on, because nobody except Scott Adams ever even thought they were worth considering:

What makes a holy land holy?” he asked.

“Well, usually it’s because some important religious event took place there.”

“What does it mean to say that something took place in a particular location when we know that the earth is constantly in motion, rotating on its axis and orbiting the sun? And we’re in a moving galaxy that is part of an expanding universe. Even if you had a spaceship and could fly anywhere, you can never return to the location of a past event. There would be no equivalent of the past location because location depends on your distance from other objects, and all objects in the universe would have moved considerably by then.”

“I see your point, but on Earth the holy places keep their relationship to other things on Earth, and those things don’t move much,” I said.

“Let’s say you dug up all the dirt and rocks and vegetation of a holy place and moved it someplace else, leaving nothing but a hole that is one mile deep in the original location. Would the holy land now be the new location where you put the dirt and rocks and vegetation, or the old location with the hole?”

“I think both would be considered holy,” I said, hedging my bets.

“Suppose you took only the very top layer of soil and vegetation from the holy place, the newer stuff that blew in or grew after the religious event occurred thousands of years ago. Would the place you dumped the topsoil and vegetation be holy?”

“That’s a little trickier,” I said. “I’ll say the new location isn’t holy because the topsoil that you moved there isn’t itself holy, it was only in contact with holy land. If holy land could turn anything that touched it into more holy land, then the whole planet would be holy.”

The old man smiled. “The concept of location is a useful delusion when applied to real estate ownership, or when giving someone directions to the store. But when it is viewed through the eyes of an omnipotent God, the concept of location is absurd. While we speak, nations are arming themselves to fight for control of lands they consider holy. They are trapped in the delusion that locations are real things, not just fictions of the mind. Many will die.”

Another quarter of the discussion is the most pusillanimous possible subjectivism, as if Robert Anton Wilson and the 2004 film What the #$*! Do We Know!? had a kid, then strangled it at birth until it came out brain damaged. We get passages like these:

“I am saying that UFOs, reincarnation, and God are all equal in terms of their reality.”

“Do you mean equally real or equally imaginary?”

“Your question reveals your bias for a binary world where everything is either real or imaginary. That distinction lies in your perceptions, not in the universe. Your inability to see other possibilities and your lack of vocabulary are your brain’s limits, not the universe’s.”

“There has to be a difference between real and imagined things,” I countered. “My truck is real. The Easter Bunny is imagined. Those are different.”

“As you sit here, your truck exists for you only in your memory, a place in your mind. The Easter Bunny lives in the same place. They are equal.”

I remember the late ‘90s and early ‘00s; I was (regrettably) there. For some reason, all this stuff was considered the height of wisdom back then. The actual Buddhist classics were hard to access, but everyone assumed that Buddhists were wise and they probably said, you know, something like this. If you said stuff like this, you could be wise too.

The final quarter of the book is a shockingly original take on the Lurianic kabbalah. I‘m not pleased to report this, and Adams likely would have been very surprised to learn it. Still, the resemblance is unmistakable. The wisest man in the world, charged with answering all of the philosophical problems that bothered you when you were nineteen, tells the following story: if God exists, He must be perfect. Therefore, the only thing he lacks is nonexistence. Therefore, in order to fill that lack, He must destroy himself in order to create the universe. The universe is composed of the fragments of that destruction - the titular God’s Debris. Its point is to reassemble itself into God. Partially-reassembled-God is not yet fully conscious, but there is some sort of instinct within His fragments - ie within the universe - that is motivated to help orchestrate the self-reassembly, and it is this instinct which causes anti-entropic processes like evolution. Good things are good because they aid in the reassembly of God; bad things are bad because they hinder it.

Adams’ version adds several innovations to this basic story. Whatever parts of God aren’t involved in physical matter have become the laws of probability; this explains the otherwise inexplicable evolutionary coincidences that created humankind. There’s something about how gravity is produced by some sort of interference between different divine corpuscules - Adams admits that Einstein probably also had useful things to say about gravity, but probably his own version amounts to the same thing, and it’s easier to understand, and that makes it better (IT’S JUST A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT! IF YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY, YOU FAIL.) But my favorite part is the augmentation of Luria with Nick Land: the final (or one of the final) steps in the divine reassembly is the creation of the Internet, aka “God’s nervous system”, which will connect everything to everything else and give the whole system awareness of its divine purpose.

I’m honestly impressed that a Gentile worked all of this out on his own. Adams completes the performance by reinventing Kegan levels (this time I’m agnostic as to whether it’s convergent evolution or simple plagiarism), although characteristically it is in the most annoying way possible:

[The wise man] described what he called the five levels of awareness and said that all humans experience the first level of awareness at birth. That is when you first become aware that you exist.

In the second level of awareness you understand that other people exist. You believe most of what you are told by authority figures. You accept the belief system in which you are raised.

At the third level of awareness you recognize that humans are often wrong about the things they believe. You feel that you might be wrong about some of your own beliefs but you don’t know which ones. Despite your doubts, you still find comfort in your beliefs.

The fourth level is skepticism. You believe the scientific method is the best measure of what is true and you believe you have a good working grasp of truth, thanks to science, your logic, and your senses. You are arrogant when it comes to dealing with people in levels two and three.

The fifth level of awareness is the Avatar. The Avatar understands that the mind is an illusion generator, not a window to reality. The Avatar recognizes science as a belief system, albeit a useful one. An Avatar is aware of God’s power as expressed in probability and the inevitable recombination of God consciousness.

I think going through every David Chapman essay and replacing the word “metarationality” with “THE AVATAR” would actually be very refreshing.

What are we to make of all of this?

Nothing is more American than inventing weird cringe fusions of religion and atheism where you say that God doesn’t exist as (gestures upward) some Big Man In The Sky the way those people believe, but also, there totally is a God, in some complicated sense which only I understand. When Thomas Jefferson cut all the passages with miracles out of his Bible, he was already standing on the shoulders of generations of Unitarians, Quakers, and Latitudinarians.

This was augmented by the vagaries of nerd culture’s intersection with the sci-fi fandom. The same people who wanted to read about spaceships and ray guns also wanted to read about psionics and Atlantis, so the smart sci-fi nerd consensus morphed into something like “probably all that unexplained stuff is real, but has a scientific explanation”. Telepathy is made up of quantum particles, or whatever (I talk about this more in my article on the Shaver Mystery). It became a nerd rite of passage to come up with your own theory that reconciled the spiritual and the material in the most creative way possible.

And the Nineties (God’s Debris was published in 2001) were a special time. The decade began with the peak of Wicca and neopaganism. Contra current ideological fault lines, where these tendencies bring up images of Etsy witches, they previously dominated nerd circles, including male nerds, techie nerds, and right-wing nerds (did you know Eric S. Raymond is neopagan?) By decade’s end, the cleverest (ie most annoying) nerds were switching to New Atheism; throughout, smaller groups were exploring Discordianism, chaos magick, and the Subgenius. The common thread was that Christianity had lost its hegemonic status, part of being a clever nerd was patting yourself on the back for having seen through it, but exactly what would replace it was still uncertain, and there was still enough piety in the water supply that people were uncomfortable forgetting about religion entirely. You either had to make a very conscious, marked choice to stop believing (New Atheism), or try your hand at the task of inventing some kind of softer middle ground (neopaganism, Eastern religion, various cults, whatever this book was supposed to be).

It’s Obvious You Won’t Survive By Your Wits Alone

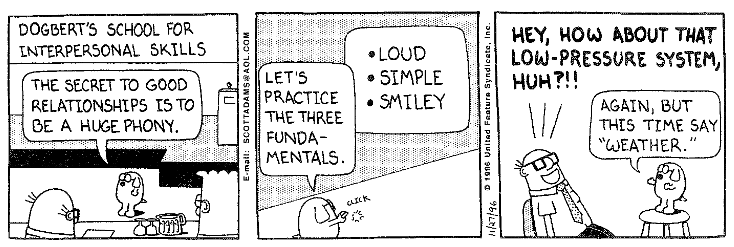

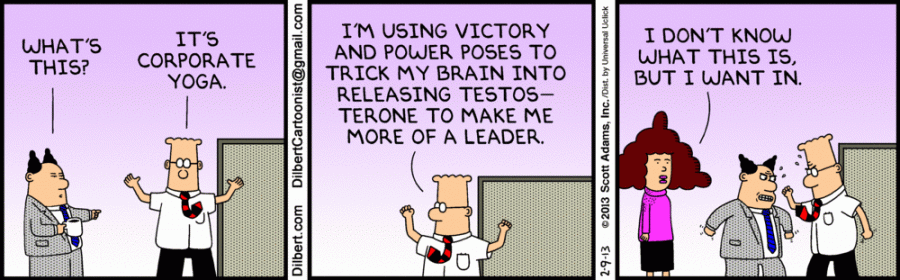

Adams spent his life obsessed with self-help. Even more than a businessman or a prophet, he wanted to be a self-help guru. Of course he did. His particular package of woo - a combination of hypnosis, persuasion hacks, and social skills advice - unified the two great motifs of his life.

Thesis: I am cleverer than everyone else.

Antithesis: I always lose to the Pointy-Haired Boss.

Synthesis: I was trying to be rational. But most people are irrational sheep; they can be directed only by charismatic manipulators who play on their biases, not by rational persuasion. But now I’m back to being cleverer than everyone else, because I noticed this. Also, I should become a charismatic manipulator.

I phrased this in a maximally hostile way, but it’s not wrong. And Adams started off strong. He read Dale Carnegie’s How To Win Friends And Influence People, widely agreed to be the classic book on social skills.

Then, in search of even stronger persuasion techniques, he turned to hypnosis. This has a bad reputation, but I basically buy that something is there. Psychiatry has legends of psychotherapist-hypnotists who achieved amazing things, and there’s a plausible scientific story for why it might work. So when Adams claimed to be a master hypnotist, I was originally willing to give him the benefit of the doubt.

That lasted until I read The Religion War3, Adams’ sequel to God’s Debris. In the intro, which may be literally the most annoying passage ever written in all two million years of human history, he discusses the reception of the original book:

This is a sequel to my book God’s Debris, a story about a deliveryman who chances upon the smartest person in the world and learns the secrets of reality. I subtitled that book A Thought Experiment and used a variety of hypnosis techniques in an attempt to produce a feeling of euphoric enlightenment in the reader similar to what the main character would feel while discovering the (fictionally) true nature of reality. Reactions to the book were all over the map. About half of the people who e-mailed me said they felt various flavors of euphoria, expanded awareness, connectedness, and other weird sensations that defied description. A surprising number of people reported reading the entire book twice in one day. So I know something was happening.

Other people wrote angry letters and scathing reviews, pointing out the logical and factual flaws in the book. It is full of flaws, and much of the science is made up, as it states in the introduction. I explained that the reader is supposed to be looking for flaws. That’s what makes the experiment work. You might think this group of readers skipped the introduction and missed the stated point of the book, but I suspect that something else is going on. People get a kind of cognitive dissonance (brain cramp) when their worldview is disturbed. It’s fun to watch.

I previously felt bad for writing this essay after Adams’ death; it seems kind of unsporting to disagree with someone who can’t respond. These paragraphs cured me of my misgivings: after his death is by far the best time to disagree with Scott Adams.

The book is a novel (a real novel this time, with plot and everything) meant to dramatize the lessons of its predecessor. In the near future, the Muslims and Christians are on the verge of global war. Adams’ self-insert character, the Avatar, goes around hypnotizing and mind hacking everyone into cooperating with his hare-brained scheme for world peace.

In an early chapter, the Christian alliance has captured the Avatar and sent him to be tortured. But the Avatar masterfully deflects the torturer’s attention with a bit of cold reading, some pointed questions, and a few hypnotic suggestions:

As the Avatar planned, the interrogator’s conscious mind was scrambled by the emotions and thoughts of the past minutes. This brutish man, accustomed to avoiding deep thoughts, had imagined the tiniest particles of the universe, his childhood, and the battles of the future. He had laughed, felt pain and pity, been intellectually stimulated, confused, assured, and uncertain. The Avatar had challenged his worldview, and it was evaporating, leaving him feeling empty, unimportant, and purposeless

In the thrilling climax, which takes place at Stacey’s Cafe (yes, it’s the real-world restaurant Adams was managing - yes, he turned his religious-apocalyptic thriller novel into an ad for his restaurant - yes, I bet he thought of this as a “hypnotic suggestion”), the characters find the Prime Influencer. She is able to come up with a short snappy slogan so memetically powerful that it defeats fundamentalist religion and ends the war (the slogan is: “If God is so smart, why do you fart?”). Adams’ mouthpiece character says:

It wasn’t the wisdom of the question that made it so powerful; philosophers had posed better questions for aeons. It was the packaging—the marketing, if you will—the repeatability and simplicity, the timing, the Zeitgeist, and in the end, the fact that everyone eventually heard it from someone whose opinion they trusted.The question was short, provocative, and cast in the language of international commerce that almost everyone understood—English. Most important, and generally overlooked by historians: It rhymed and it was funny. Once you heard it, you could never forget it. It looped in the brain, gaining the weight and feel of truth with each repetition. Human brains have a limited capacity for logic and evidence. Throughout time, repetition and frequency were how people decided what was most true.

This paragraph is the absolute center of Adams’ worldview (later expanded to book length several times in tomes named things like Win Bigly: Persuasion In A World Where Facts Don’t Matter). People don’t respond to logic and evidence, so the world is ruled by people who are good at making catchy slogans. Sufficiently advanced sloganeering is indistinguishable from hypnosis, and so when Adams has some cute turns of phrase in his previous book, he describes it as “[I] used a variety of hypnosis techniques in an attempt to produce a feeling of euphoric enlightenment in the reader”. This is the cringiest way possible to describe cute turns of phrase, and turns me off from believing any his further claims to hypnotic mastery.

Throughout this piece, I’ve tried to emphasize that Adams was usually pretty self-aware. Did that include the hypnosis stuff? I’m not sure. I think he would have answered: certainly some people are great charismatic manipulators. Either their skills are magic, or they operate by some physical law. If they operate by physical law, they should be learnable. Maybe I’m not quite Steve Jobs level yet, but I have to be somewhere along the path to becoming Steve Jobs, right? And why not describe it in impressive terms? Steve Jobs would have come up with impressive-sounding terms for any skills he had, and you would have believed him!

Every few months, some group of bright nerds in San Francisco has the same idea: we’ll use our intelligence to hack ourselves to become hot and hard-working and charismatic and persuasive, then reap the benefits of all those things! This is such a seductive idea, there’s no reason whatsoever that it shouldn’t work, and every yoga studio and therapist’s office in the Bay Area has a little shed in the back where they keep the skulls of the last ten thousand bright nerds who tried this. I can’t explain why it so invariably goes wrong. The best I can do is tell a story where, when you’re trying to do this, you’re selecting for either techniques that can change you, or techniques that can compellingly make you think you’ve been changed. The latter are much more common than the former. And the most successful parasites are always those which can alter their host environment to be more amenable to themselves, and if you’re a parasite taking the form of a bad idea, that means hijacking your host’s rationality. So you’re really selecting for things that are compelling, seductive, and damage your ability to tell good ideas from bad ones. This is a just-so story that I have no evidence for - but seriously, go to someone who has the words “human potential” on their business card and ask them if you can see the skull shed.

But also: it’s attractive to be an effortlessly confident alpha male who oozes masculinity. And it’s . . . fine . . . to be a normal person with normal-person hangups. What you really don’t want to be is a normal person who is unconvincingly pretending to be a confident alpha male. “Oh hello, nice to meet you, I came here in my Ferrari, it’s definitely not a rental, you’re having the pasta - I’m choosing it for you because I’m so dominant - anyway, do you want to have sex when we get back? Oh, wait, I forgot to neg you, nice hair, is it fake?”

In theory, becoming a hot charismatic person with great social skills ought to be the same kind of task as everything else, where you practice a little and you’re bad, but then you practice more and you become good. But the uncanny valley is deep and wide, and Scott Adams was too invested in saying “Ha! I just hypnotized you - ha! There, did it again!” for me to trust his mountaineering skills.

Don’t Step In The Leadership

It all led, inexorably, to Trump.

In summer 2015, Trump came down his escalator and announced his presidential candidacy. Given his comic status, his beyond-the-pale views, and his competition with a crowded field including Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz, traditional media wrote him off. Sure, he immediately led in the polls, but political history was full of weirdos who got brief poll bumps eighteen months before an election only to burn out later. The prediction markets listed his chance of the nomination (not the Presidency!) at 5%.

Which made it especially jarring when, in August, Scott Adams wrote a blog post asserting that Trump had “a 98% chance” of winning. This claim received national attention, because Trump was dominating the news cycle and Adams was approximately the only person, anywhere, who thought he had a chance.

There are two ways to make historically good predictions. The first way is to be some kind of brilliant superforecaster. Adams wasn’t this. Every big prediction he made after this one failed. Wikipedia notes that he dominated a Politico feature called “The Absolute Worst Political Prediction of 20XX”, with the authors even remarking that he “has managed to appear on this annual roundup of the worst predictions in politics more than any other person on the planet”. His most famous howler was that if Biden won in 2020, Republicans “would be hunted” and his Republican readers would “most likely be dead within a year”. But other highlights include “a major presidential candidate will die of COVID”, “the Supreme Court will overturn the 2024 election”, and “Hillary Clinton will start a race war”.

The other way to make a great prediction is to live your entire life for one perfect moment - the inveterate bear who predicted twelve of the last zero recessions, but now it’s 2008 and you look like a genius. By 2015, Adams had become a broken record around one point: people are irrational sheep who are prey for charismatic manipulators. The pointy-haired boss always wins. Trump was the pointiest-haired person in the vicinity, and he was obviously trying to charismatically play on people’s instincts while other people were doing comparatively normal politics. Scott Adams’ hour had arrived.

But Adams also handled his time in the spotlight masterfully. He gave us terms like “clown genius”. I hate using this, because I know Scott Adams was sitting at his desk in his custom-built Dilbert-head-shaped tower thinking “What sort of hypnotic catchy slogans can I use to make my meme about Trump spread . . . aha! Clown genius! That has exactly the right ring!” and it absolutely worked, and now everyone who was following the Internet in 2015 has the phrase “clown genius” etched into their brains (Adams calls these “linguistic kill shots”; since I remember that term and use it often, I suppose “linguistic kill shot” is an example of itself). He went from news outlet to news outlet saying “As a trained hypnotist, I can tell you what tricks Trump is using to bamboozle his followers, given that rational persuasion is fake and marketing techniques alone turn the wheels of history,” and the news outlets ate it up.

And some of his commentary was good. He was one of the first people to point out the classic Trump overreach, where he would say something like “Sleepy Joe Biden let in twenty trillion illegal immigrants!” The liberal media would take the bait and say “FACT CHECK: False! - Joe Biden only let in five million illegal immigrants!”, and thousands of people who had never previously been exposed to any narrative-threatening information would think “Wait, Joe Biden let in five million illegal immigrants?!” Once you notice it, it’s hard to unsee.

Adams started out by stressing that he was politically independent. He didn’t support Trump, he was just the outside hypnosis expert pointing out what Trump was doing. IT’S JUST A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT, IF YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY, YOU FAIL. Indeed, “this person is a charismatic manipulator hacking the minds of irrational sheep” is hardly a pro-Trump take. And he lived in Pleasanton, California - a member in good standing of the San Francisco metropolitan area - and nice Pleasantonians simply did not become Trump supporters in 2016.

On the other hand, at some point, his increasingly overblown theories of Trump’s greatness opened up a little wedge. The growing MAGA movement started treating him as one of their own; liberals started to see him as an enemy. His fame turned the All-Seeing Eye of social media upon him, that gaze which no man may meet without consequence. Once you’re sufficiently prominent, politics becomes a separating equilibrium; if you lean even slightly to one side, the other will pile on you so massively and traumatically that it will force you into their opponents’ open arms just for a shred of psychological security.

As he had done so many other times during his life, he resolved the conflict in the dumbest, cringiest, and most public way possible: a June 2016 blog post announcing that he was endorsing Hillary Clinton, for his own safety, because he suspected he would be targeted for assassination if he didn’t:

This past week we saw Clinton pair the idea of President Trump with nuclear disaster, racism, Hitler, the Holocaust, and whatever else makes you tremble in fear. That is good persuasion if you can pull it off because fear is a strong motivator. It is also a sharp pivot from Clinton’s prior approach of talking about her mastery of policy details, her experience, and her gender. Trump took her so-called “woman card” and turned it into a liability. So Clinton wisely pivoted. Her new scare tactics are solid-gold persuasion. I wouldn’t be surprised if you see Clinton’s numbers versus Trump improve in June, at least temporarily, until Trump finds a counter-move.

The only downside I can see to the new approach is that it is likely to trigger a race war in the United States. And I would be a top-ten assassination target in that scenario […]

So I’ve decided to endorse Hillary Clinton for President, for my personal safety. Trump supporters don’t have any bad feelings about patriotic Americans such as myself, so I’ll be safe from that crowd. But Clinton supporters have convinced me – and here I am being 100% serious – that my safety is at risk if I am seen as supportive of Trump. So I’m taking the safe way out and endorsing Hillary Clinton for president.

As I have often said, I have no psychic powers and I don’t know which candidate would be the best president. But I do know which outcome is most likely to get me killed by my fellow citizens. So for safety reason, I’m on team Clinton.

My prediction remains that Trump will win in a landslide based on his superior persuasion skills. But don’t blame me for anything President Trump does in office because I endorse Clinton.

This somehow failed to be a masterstroke of hypnotic manipulation that left both sides placated. But it was fine, because Trump won anyway! In the New Right’s wave of exultation, all was forgiven, and the first high-profile figure to bet on Trump became a local hero and confirmed prophet. Never mind that Adams had predicted Trump would win by “one of the biggest margins we’ve seen in recent history” when in fact he lost the popular vote. The man who had dreamed all his life of being respected for something other than cartooning had finally made it.

Obviously, it destroyed him.

At first, I wondered if Adams’ right-wing turn was a calculated manuever. He’d always longed to be a manipulator of lesser humans, and had finally achieved slightly-above-zero skill at it. Wouldn’t it fit his personality to see the right-wingers as dumb sheep, and himself as the clever Dogbert-style scammer who could profit off them? Did he really believe (as he claimed) that he was at risk of being assassinated by left-wing radicals who couldn’t handle his level of insight into Trump’s genius? Or was this just another hypnotic suggestion, retrospectively justified insofar as we’re still talking about it ten years later and all publicity is good publicity?

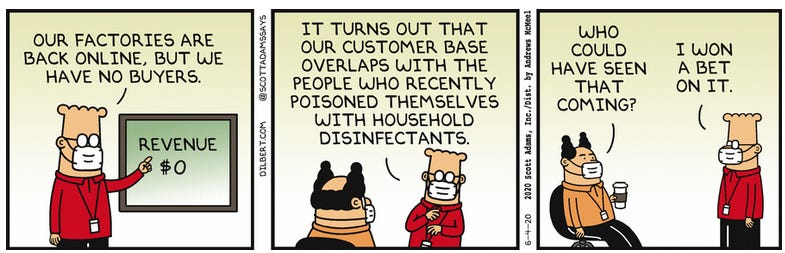

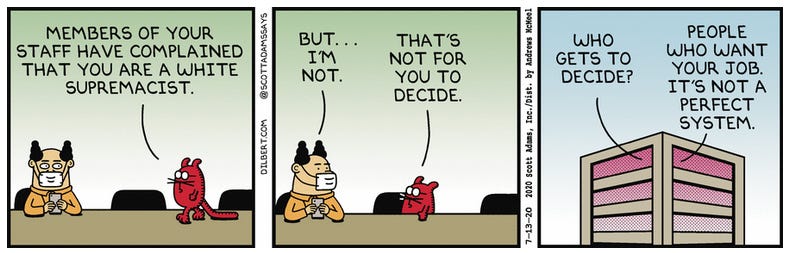

But I don’t think he did it cynically. At the turn of the millennium, the obsessed-with-their-own-cleverness demographic leaned firmly liberal: smug New Atheists, hardline skeptics, members of the “reality-based community”. But in the 2010s, liberalism became the default, the public switched to expertolatry, dumb people’s orthodoxies about race and gender became easier and more fun to puncture than dumb people’s orthodoxies about religion - and the O.W.T.O.C.s lurched right. Adams was borne along by the tide. With enough time, dedication, and archive access, you can hop from Dilbert comic to Dilbert comic, tracing the exact contours of his political journey.

There’s a passage in the intro to one of Adams books where he says that, given how he’s going to blow your mind and totally puncture everything you previously believed, perhaps the work is unsuitable for people above fifty-five, whose brains are comparatively sclerotic and might shatter at the strain. This is how I feel about post-2016 politics. Young people were mostly able to weather the damage. As for older people, I have seen public intellectual after public intellectual who I previously respected have their brains turn to puddles of partisan-flavored mush. Jordan Peterson, Ken White, Curtis Yarvin, Paul Krugman, Elon Musk, the Weinsteins, [various people close enough to me that it would be impolite to name them here]. Once, these people were lions of insightful debate. Where now are the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Adams was 58 when Trump changed everything. In 2001, age 44, he’d found the failure of his Dilberito funny. But in another interview, at age 50, he suggested that maybe his competitors had formed teams to sneak into supermarkets and hide them in the back of the shelves. Being tragically flawed yet also self-aware enough to laugh about it is a young man’s game.

In 2024, diagnosed with terminal cancer, Adams decided to treat it via ivermectin, according to a protocol recommended by fellow right-wing contrarian Dr. William Makis. This doesn’t seem to me like a story about a cynic milking right-wingers for the grift. It sounds like a true believer. Scott Adams, the man too clever and independent to join any political tendency, who had sworn to always be the master manipulator standing above the fray rather than a sheep with ordinary object-level opinions - had finally succumbed to sincere belief.

It’s Not Funny If I Have To Explain It

Every child is hypomanic, convinced of their own specialness. Even most teenagers still suspect that, if everything went right, they could change the world.

It’s not just nerds. Everyone has to crash into reality. The guitar player who starts a garage band in order to become a rockstar. The varsity athlete who wants to make the big leagues. They all eventually realize, no, I’m mediocre. Even the ones who aren’t mediocre, the ones with some special talent, only have one special talent (let’s say cartooning) and no more.

I don’t know how the musicians and athletes cope. I hear stories about washed-up alcoholic former high school quarterbacks forever telling their girlfriends about how if Coach had only put them in for the last quarter during the big game, things would have gone differently. But since most writers are nerds, it’s the nerds who dominate the discussion, so much so that the whole affair gets dubbed “Former Gifted Kid Syndrome”.

Every nerd who was the smartest kid in their high school goes to an appropriately-ranked college and realizes they’re nothing special. But also, once they go into some specific field they find that intellect, as versatile as it is, can only take them so far. And for someone who was told their whole childhood that they were going to cure cancer (alas, a real quote from my elementary school teacher), it’s a tough pill to swallow.

Reaction formation, where you replace a unbearable feeling with its exact opposite, is one of the all time great Freudian defense mechanisms. You may remember it from such classics as “rape victims fall in love with their rapist” or “secretly gay people become really homophobic”. So some percent of washed-up gifted kids compensate by really, really hating nerdiness, rationality, and the intellect.

The variety of self-hating nerd are too many to number. There are the nerds who go into psychology to prove that EQ is a real thing and IQ merely its pale pathetic shadow. There are the nerds who become super-woke and talk about how reason and objectivity are forms of white supremacy culture. There are the nerds who obsess over “embodiment” and “somatic therapy” and accuse everyone else of “living in their heads”. There are the nerds who deflect by becoming really into neurodiversity - “the interesting thing about my brain isn’t that I’m ‘smart’ or ‘rational’, it’s that I’m ADHDtistic, which is actually a weakness . . . but also secretly a strength!” There are the nerds who flirt with fascism because it idolizes men of action, and the nerds who convert to Christianity because it idolizes men of faith. There are the nerds who get really into Seeing Like A State, and how being into rationality and metrics and numbers is soooooo High Modernist, but as a Kegan Level Five Avatar they are far beyond such petty concerns. There are the nerds who redefine “nerd” as “person who likes Marvel movies” - having successfully gerrymandered themselves outside the category, they can go back to their impeccably-accurate statisticsblogging on educational outcomes, or their deep dives into anthropology and medieval mysticism, all while casting about them imprecations that of course nerds are loathsome scum who deserve to be bullied.

(maybe it’s unfair to attribute this to self-hatred per se. Adams wrote, not unfairly, that the scientismists in Kegan level 4 “are arrogant when it comes to dealing with people in levels two and three.” Maybe there’s the same desperate urge for level 5 to differentiate themselves from 4s - cf. barberpole theory of fashion).

Scott Adams felt the contradictions of nerd-dom more acutely than most. As compensation, he was gifted with two great defense mechanisms. The first was humor (which Freud grouped among the mature, adaptive defenses), aided by its handmaiden self-awareness. The second (from Freud’s “neurotic” category) was his own particular variety of reaction formation, “I’m better than those other nerds because, while they foolishly worship rationality and the intellect, I’ve gotten past it to the real deal, marketing / manipulation / persuasion / hypnosis.”

When he was young, and his mind supple, he was able to balance both these mechanisms; the steam of their dissonance drove the turbine of his art. As he grew older, the first one - especially the self-awareness - started to fail, and he leaned increasingly heavily on the second. Forced to bear the entire weight of his wounded psyche, it started showing more and more cracks, until eventually he ended up as a podcaster - the surest sign of a deranged mind.

In comparison, his final downfall was almost trivial - a bog-standard cancellation, indistinguishable from every other cancellation of the 2015 - 2025 period. Angered by a poll where some black people expressed discomfort with the slogan “It’s Okay To Be White”, Adams declared that “the best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from black people; just get the fuck away”. Needless to say, his publisher, syndicator, and basically every newspaper in the country dropped him immediately. He relaunched his comics on Locals, an online subscription platform for cancelled people, but his reach had declined by two orders of magnitude and never recovered.

Adams was willing to sacrifice everything for the right to say “It’s Okay To Be White”. I can’t help wondering what his life would have been like if he’d been equally willing to assert the okayness of the rest of his identity.

Dilbert's Guide to the Rest of Your Life

In case it’s not obvious, I loved Scott Adams.

Partly this is because we’re too similar for me to hate him without hating myself. You’re a bald guy with glasses named Scott A who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. You think you’re pretty clever, but the world has a way of reminding you of your limitations. You try to work a normal job. You do a little funny writing on the side. People like the funny writing more than you expected. Hardly believing your luck, you quit to do the funny writing full time. You explore themes about the irrationality of the world. You have some crazy ideas you’re not entirely willing to stand behind, and present them as fiction or speculation or April Fools jokes. You always wonder whether your purpose in life is really just funny writing - not because people don’t love the stuff you write, not even because you don’t get fan mail saying you somehow mysteriously changed people’s lives, but just because it seems less serious than being a titan of industry or something. You try some other things. They don’t go terribly, but they don’t go great either. You decide to stick with what you’re good at. You write a book about the Lurianic kabbalah. You get really into whale puns.

As we pass through life, sometimes God shows us dopplegangers, bright or dark mirrors of ourselves, glimpses of how we might turn out if we zig or zag on the path ahead. Some of these people are meant as shining inspirations, others as terrible warnings, but they’re all our teachers.

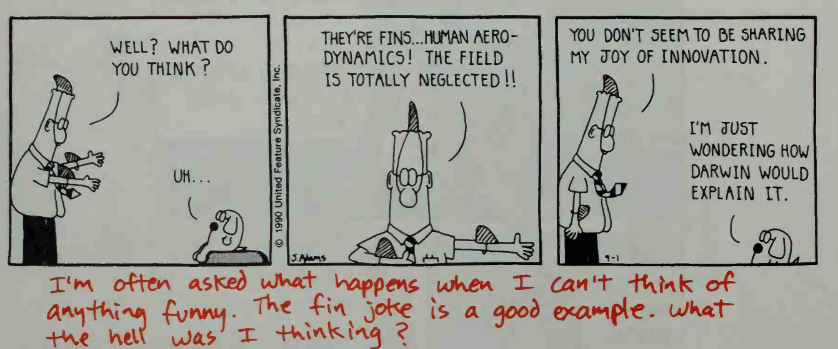

Adams was my teacher in a more literal way too. He published several annotated collections, books where he would present comics along with an explanation of exactly what he was doing in each place, why some things were funny and others weren’t, and how you could one day be as funny as him. Ten year old Scott devoured these. I’ve always tried to hide my power level as a humorist, lest I get pegged as a comedic author and people stop taking me seriously. But objectively my joke posts get the most likes and retweets of anything I write, and I owe much of my skill in the genre to cramming Adams’ advice into a malleable immature brain4. There’s a direct line between Dogbert’s crazy schemes and the startup ideas in a typical Bay Area House Party post.

The Talmud tells the story of the death of Rabbi Elisha. Elisha was an evil apostate. His former student, Rabbi Meir, who stayed good and orthodox, insisted that Rabbi Elisha probably went to Heaven. This was never very plausible, and God sent increasingly obvious signs to the contrary, including a booming voice from Heaven saying that Elisha was not saved. Out of loyalty to his ex-teacher, Meir dismissed them all - that voice was probably just some kind of 4D chess move - and insisted that Elisha had a share in the World To Come.

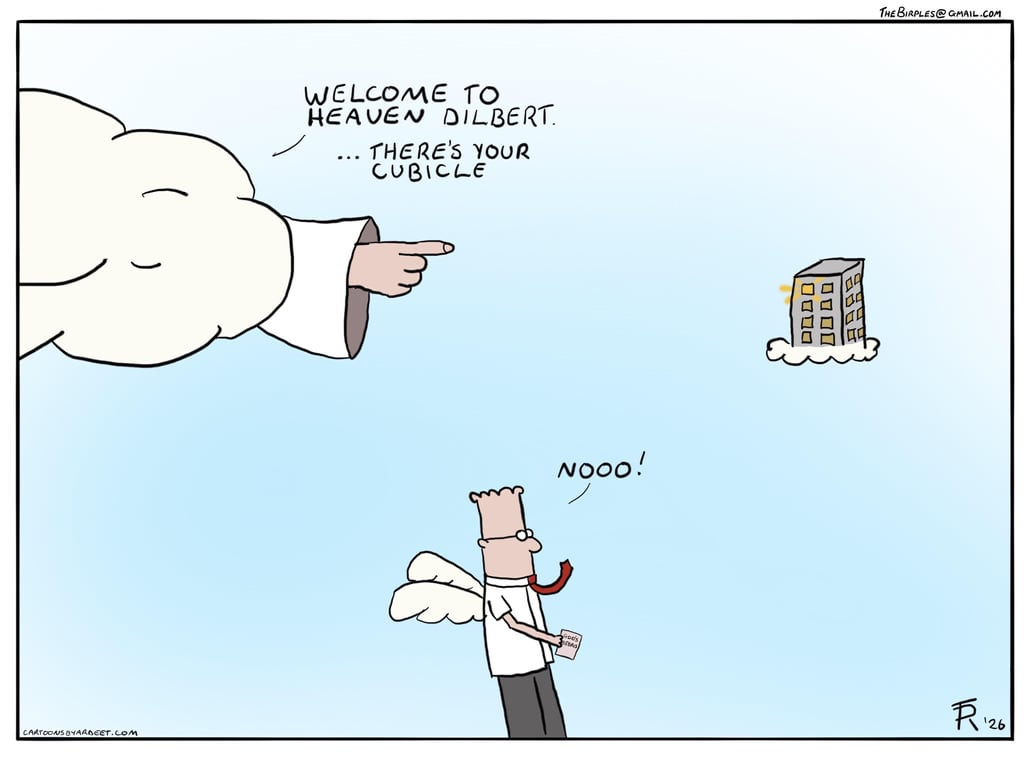

Out of the same doomed loyalty as Rabbi Meir, I want to believe Scott Adams went to Heaven.

There is what at first appears to be promising evidence - in his final message to his fans, Adams said:

Many Christian friends have asked me to find Jesus before I go. I’m not a believer, but I have to admit the risk-reward calculation for doing so looks attractive. So here I go: I accept Jesus Christ as my lord and savior, and I like forward to spending an eternity with him. The part about me not being a believer should be quickly resolved if I wake up in heaven. I won’t need any more convincing than that. And I hope I am still qualified for entry.

It is a dogma of many religions that sincere deathbed conversions are accepted. But I’d be more comfortable if this sounded less like “haha, I found my final clever lifehack”. I can only hope he didn’t try to implant any hypnotic suggestions in an attempt to get a linguistic kill shot in on the Almighty. As another self-hating nerd writer put it, “through all these years I make experiment if my sins or Your mercy greater be.”

But I’m more encouraged by the second half of his departing note:

For the first part of my life, I was focused on making myself a worthy husband and parent, as a way to find meaning. That worked. But marriages don't always last forever, and mine eventually ended, in a highly amicable way. I'm grateful for those years and for the people I came to call my family.

Once the marriage unwound, I needed a new focus. A new meaning. And so I donated myself to "the world," literally speaking the words out loud in my otherwise silent home. From that point on, I looked for ways I could add the most to people's lives, one way or another.

That marked the start of my evolution from Dilbert cartoonist to an author of - what I hoped would be - useful books. By then, I believed I had condensed enough life lessons that I could start passing them on. I continued making Dilbert comics, of course.

As luck would have it, I'm a good writer. My first book in the "useful" genre was How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big. That book turned out to be a huge success, often imitated, and influencing a wide variety of people. I still hear every day how much that book changed lives. My plan to be useful was working.

I followed up with my book Win Bigly, that trained an army of citizens how to be more persuasive, which they correctly saw as a minor super power. I know that book changed lives because I hear it often.

You'll probably never know the impact the book had on the world, but I know, and it pleases me while giving me a sense of meaning that is impossible to describe.

My next book, Loserthink, tried to teach people how to think better, especially if they were displaying their thinking on social media. That one didn't put much of a dent in the universe, but I tried.

Finally, my book Reframe Your Brain taught readers how to program their own thoughts to make their personal and professional lives better. I was surprised and delighted at how much positive impact that book is having.

I also started podcasting a live show called Coffee With Scott Adams, dedicated to helping people think about the world, and their lives, in a more productive way. I didn't plan it this way, but it ended up helping lots of lonely people find a community that made them feel less lonely. Again, that had great meaning for me.

I had an amazing life. I gave it everything I had. If you got any benefits from my work, I'm asking you to pay it forward as best you can. That is the legacy I want.Be useful.

And please know I loved you all to the end.

I had been vaguely aware that he had some community around him, but on the event of his death, I tried watching an episode or two of his show. I couldn’t entirely follow, but I think his various sub-shows are getting rolled into a broader brand, The Scott Adams School, where his acolytes discuss and teach his theory of persuasion:

The woman on the top left is his ex-wife. Even though they’ve been divorced for twelve years, they never abandoned each other. All the other faces are people who found Adams revelatory and are choosing to continue his intellectual tradition. And in the comments - thirteen thousand of them - are other people who loved Adams. Some watch every episode of his podcast and consider him a genius. Others were touched in more subtle ways. People who wrote him with their problems and he responded. People who met him on the street and demanded the typical famous person “pose for a photo with me”, and he did so graciously. People who said his self-help books really helped them. People who just used Dilbert to stay sane through their cubicle jobs.

(also one person blaming his death on the COVID vaccine, but this is Twitter, you’re never going to avoid that)

Adams is easy and fun to mock - as is everyone who lives their life uniquely and unapologetically. I’ve had a good time psychoanalyzing him, but everyone does whatever they do for psychological reasons, and some people end up doing good.

Though I can’t endorse either Adams’ politics or his persuasive methods, everything is a combination of itself and an attempt to build a community. And whatever the value of his ideas, the community seems real and loving.

And I’m serious when I say I consider Adams a teacher. For me, he was the sort of teacher who shows you what to avoid; for many others, he was the type who serves as inspiration. These roles aren’t quite opposites - they’re both downstream of a man who blazed his own path, and who recorded every step he took, with unusual grace and humor, as documentation for those who would face a choice of whether or not to follow. This wasn’t a coincidence, but the conscious and worthy project of his life. Just for today, I’ll consider myself part of the same student body as all the other Adams fans, and join my fellows in tribute to our fallen instructor.

I hope he gets his linguistic kill shot in on God and squeaks through the Pearly Gates.

As is quantum complexity blogger Scott Aaronson.

Cf. the old joke about the Soviet Jew trying to emigrate to Israel. The secret police is giving him a hard time - “What don’t you like about our communist paradise? You think the economy is too weak?” “Oh no, I can’t complain.” “You think the politics are oppressive?” “Oh no, I can’t complain.” “You think we prevent you from practicing your primitive religion?” “Oh no, I can’t complain.” “Then why do you want to leave for Israel?” “Because there, I can complain.”

"What’s the normal English term for when holy people fight over holy sites because of their differing beliefs about what is holy? Oh, right, a Religion War.”

To be more precise, half of my skill. I attribute the other half to Dave Barry, who I consumed the same way during the same period of my life.