Sorry, I Still Think MR Is Wrong About USAID

...

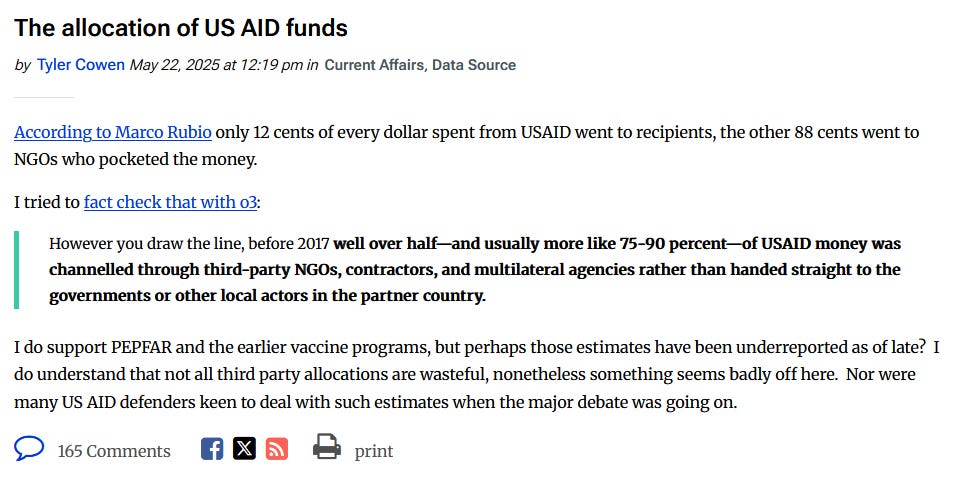

Tyler Cowen of Marginal Revolution continues to disagree with my Contra MR On Charity Regrants. Going through his response piece by piece, slightly out of order:

Scott takes me to be endorsing Rubio’s claim that the third-party NGOs simply pocket the money. In reality my fact check with o3 found (correctly) that the money was “channelled through” the NGOs, not pocketed. Scott lumps my claim together with Rubio’s as if we were saying the same thing. My very next words (“I do understand that not all third party allocations are wasteful…”) show a clear understanding that the money is channeled, not pocketed, and my earlier and longer post on US AID makes that clearer yet at greater length. Scott is simply misrepresenting me here.

The full post is in the image below:

Maybe I’m just revealing my poor reading comprehension, but I think that:

Starting with Rubio’s claim that only 12% goes to recipients because 88% is “pocketed”…

Then saying you are going to “fact check” it…

Then quoting and bolding sentence from the “fact check” which includes a claim that 75-90% goes to “third parties”, as if this is a “fact-check” of the 88% number which finds it correct…

Then saying that it demonstrates “something is badly off here”, when correctly understood it would not demonstrate that at all (at least not without some kind of unusual and very controversial argument for why giving to partners must be bad)...

Then saying that USAID defenders were unwilling to consider this when the “debate” (about Rubio’s claims) was going on…

…will inevitably lead to people thinking Tyler is confirming or at least directionally agreeing with Rubio.

I wasn’t the only person who understood it this way. So did eleven people who commented to this effect on the ACX subreddit1, 22 people who commented this on Marginal Revolution itself, a Yale economics professor , a Center for Global Development senior economist - and, presumably, my friend who, when I told them last week that I had a post I wanted them to proofread, responded, without even knowing what it was about, I quote, "before clicking on the link my guess is it's about tyler cowen's inane USAID post...I was so angry".

So I apologize for any misunderstanding I may have had, but I think Tyler should also consider apologizing for a post that may have been unclear to a lot of people.

Someone should tell [Scott] that Emergent Ventures overhead is typically two percent, five percent for dealing with screwier banking systems. (That is one reason why I won the recent Time magazine award for innovation in philanthropy.) I am well aware there are various ways of calculating overhead, but there are now more than one thousand Emergent Ventures winners, and all of them can testify to how radically stripped-down the process is.

The overhead for ACX Grants is 0%; I agree that it’s important to try to keep overhead as low as possible. So why do USAID charities have higher overhead than Tyler’s regrants?

My original hypothesis was that it’s more expensive to run a system of African clinics than a grants program. But in the process of trying to confirm, I found that wasn’t the answer at all. It’s because the 30% number I gave yesterday is an accounting concept called NICRA which is often cited as overhead, but different from the common-sense conception.

Let’s consider a typical USAID partner NGO. To avoid accusations of cherry-picking, we’ll take the biggest one: Catholic Relief Services, which operates a series of clinics throughout Africa. USAID gives them about $500 million per year, and they get another $1 billion from other donors.

Their NICRA is 27%, which matches the 30% number I gave yesterday (CTRL+F “NICRA” here). But the percent of their money spent on administrative costs , which is probably closer to what most people mean by overhead, was 6.3% (supporting/total on page 22 here). Of that 6.3%, about 4%pp went to salaries and 2%pp to fundraising.

Why is NICRA so much higher than true overhead? I’m not an accountant, but my understanding of this document suggests NICRA is a legal fiction negotiated with the United States government in a way that is convenient for funding but has different numerators and denominators than real expenses. Because many real contributions and expenses cannot be included in the denominator, the overall rate appears artificially high.

(is CRS unusual in its low overhead, maybe because of its Catholic affiliation? I checked one of USAID’s biggest secular partners, the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education on Obstetrics and Gynecology (JHPIEGO), which despite its name operates AIDS, malaria, and COVID clinics in Africa. Its NICRA was 17% and its true overhead was 3.9%, and I couldn’t otherwise find any big difference from CRS.)

Is it bad that CRS spends 4% on salaries? That’s $60 million of their $1.5 billion budget. They say this includes finance, HR, legal, internal audit, IT, risk-management, and insurance. Does a $1.5 billion charity really need $60 million worth of audits, risk management, insurance, etc? I don’t know, but it seems harsh to blow up the whole thing because you’re mad about 4%.

What does the 94% non-administrative money go to? The largest category is food (to feed starving people in developing countries). The second-largest is salaries (for local personnel like doctors and nurses).

The third-largest category (20%, so $300 million of their total $1.5 billion yearly budget) is the types of re-re-grants people are concerned about. Sometimes they give the money to their local Catholic equivalent, like Caritas Nigeria. In some war-torn places, they give the money to local groups that are already stuck in the war-torn area instead of trying to send American staffers in themselves - I think this is what’s going on in the Joint Emergency Operation in Tigray.

Why doesn’t USAID give grants to these groups directly, instead of giving them to CRS to give grants to them? Sometimes it’s because random locals in Tigray with a comparative advantage in dodging warlords don’t also have a comparative advantage in interfacing with the US government, which demands large amounts of paperwork. Other times it’s because these are such small grants that they’re a bad match for USAID’s long application and compliance process. Still other times, it’s because CRS has more people on the ground and more expertise in figuring out who needs money.

Do these groups charge an additional overhead layer? I’m having trouble figuring this out. This seems to suggest CRS isn’t allowed to charge its own overhead on anything beyond the first $50,000 that it sub-grants - but I’m not sure I’m understanding it correctly. In other cases, CRS pays the other charities’ overheads out of its own overhead costs. I can’t get a great read on how often grants really are double-overheaded. But for CRS, it seems like the absolute worst case scenario, where all of its regrants have double overhead, is something like 7.2% total overhead (6% CRS overhead, plus another 6% partner overhead on the 1/5 of its money that it gives to partners).

In the original post, I was imagining something like a 30% overhead plus another layer of 10% overhead totalling 40%. But it’s really more like 7.2%. So I got this one extremely wrong, sorry. The reason I didn’t catch this was that I thought that certain program expenses (like doctor salaries) were included in overhead, so “30% overhead” didn’t immediately stand out as crazy to me. I have added this to my Mistakes page and regret the error.

Anyway, Tyler’s 2-5% grant program overhead is pretty similar to the real overhead of CRS, JHPIEGO, and presumably other USAID charities, so I don’t think there’s a mystery here.

Scott could have simply asked me how [Mercatus overhead] works. It is also the case that we do not receive or seek federal government research funding, but if we did the overhead going to GMU would be zero (are you listening o3?). Depending on the exact source of the funding, very likely we would make a lot of money on such grants because we would receive significant “overhead” payments for what would not be actual overhead expenses. That is one big problem with the system, I might add. We at Mercatus have made the judgment that we do not wish to become institutionally/financially addicted to such overhead…and I wish more non-profits would do the same.

In my original post, I quoted o3 saying that Mercatus took about 8% as direct overhead, and that many other administrative expenses that a normal charity would have to charge as overhead were instead covered by George Mason University, but that under normal federal grant rules these would count for about 30%. I didn’t mean to imply that Mercatus actually took federal funding or charged these numbers (which is why I used the hypothetical “if” on that statement) and if it came off this way, I’m sorry. But other than that, I’m not sure what Tyler is objecting to.

The 8% number comes from Mercatus’ 990 form here - management + general + fundraising as a percent of total expenses (again, compare to Catholic Relief Services’ 6%).

The claim that George Mason covers services that would usually have to be charged as overhead is also well-cited; for example, this article says that Mercatus rents its office space from GMU for a cost of $1 for a twenty-eight year lease - surely not the market price in Northern Virginia.

There’s nothing wrong with this - ACX Grants maintains its 0% overhead because Manifund covers our bills. My point is that it’s nothing to be proud of either. Mercatus hasn’t discovered some amazing new way to do charity without overhead costs, such that USAID charities that charge overhead are bloated and wasteful, but Mercatus is innovative and lean. They’ve just found someone who covers many of their bills for free.

There was an earlier time when US AID did much less channeling through American third party NGOs. That was in my view a better regime, though of course Congress wanted to spend more money on Americans, and furthermore parts of the Republican Party, often in the executive branch, viewed the NGO alternative as more flexible and also more market-friendly. That created a small number of triumphs, such as PEPFAR, and a lot of waste, and I am happy to clear away much of that waste. Doing so also will improve aid decision-making in the future. It is right to believe that US AID can operate on another basis, and also right to wish to stop a system that allows spending on ostensible “democracy promotion.” I find it a useful discipline to have an initial approach to the problem that starts with this question “if you can’t find poverty-fighting domestic institutions in a country to fund directly, with sufficient trust, perhaps you should be giving aid elsewhere.” I also find it plausible that doing a lot of initial and pretty radical clearing away of NGO relations is the best way to get there, though I agree that point is debatable.

Why? Are local charities more efficient than US charities? I don’t know, and I see no evidence that Cowen knows either. I suppose they might take less than 6% in overhead, since salaries are cheaper there and there are fewer compliance costs. But they also seem to have a lot of corrupt warlords in those countries, and “fewer compliance costs” is not an unalloyed good.

I would love to see a careful analysis of whether it’s more efficient to fund local vs. US charities. If it turned out the answer was local charities, then I would support a transition plan to get as much USAID money distributed locally as possible while causing as little disruption to on-the-ground services as possible. My impression is that pre-Trump USAID was actually in the middle of something like this (they had identified a target of 50% locals, but were having trouble finding good ones).

What instead happened was that almost all USAID programs were simply terminated, with no attention to minimizing disruption, and no plan to replace them with local charities, and so probably several million people will die. If Tyler will condemn this as a terrible decision, then we’re on the same page and everything else here is minor nitpicking. But if this is what he means by the “radical clearing away of NGO relations” that he finds “plausible” as “the best way”, then we’re not at all on the same page and I think Tyler should say so clearly and admit he disagrees with me.

Also - “I find it a useful discipline to have an initial approach to the problem that starts with this question ‘if you can’t find poverty-fighting domestic institutions in a country to fund directly, with sufficient trust, perhaps you should be giving aid elsewhere.’” Why? Switzerland has great institutions - should we give our charity money there? There’s a obvious tension between the two goals of giving charity to countries dysfunctional enough to need it, but functional enough to use it effectively. Existing international aid is a complex balance between these two goals, and using (functional) US institutions to help get charity into (dysfunctional) countries is one proposed solution. There are probably others, and maybe Tyler has one in mind, but he doesn’t argue for it here, just gives a sort of faux-profound slogan.

Scott writes: “When Trump and Rubio try to tar them [US AID] as grifters in order to make it slightly easier to redistribute their Congress-earmarked money to kleptocrats and billionaire cronies, this goes beyond normal political lying into the sort of thing that makes you the scum of the earth, the sort of person for whom even an all-merciful God could not restrain Himself from creating Hell.” Is that how the rationalist community should be presenting itself? In a time when innocent Americans are gunned down in the streets for their (ostensible) political views, and political assassination attempts seem to be rising, and there even has been a rationalist murder cult running around, does this show a morally responsible and clear thinking approach to the post that was published?

I want to make it clear: I am not recommending that people kill Donald Trump or Marco Rubio. I am recommending that God consider sending them to Hell. I think this is a moderate compromise proposal, endorsed by leading Hell experts2.

I reject the claim that criticism is tantamount to violence - a claim which anyway I usually hear applied to transgender sex workers rather than, say, Donald Trump. Partly this is because I think a writer’s first responsibility is to to truth, second to goodness, and only very far down the list to manage the emotions of some hypothetical psychopath who may or may not be reading their work.

But primarily it’s because applied consistently, it makes it impossible to ever criticize anything - after all, even the most tepid criticism could fuel someone sufficiently on the edge. This is impractical, so nobody ever does apply it consistently, so it inevitably ends up as an isolated demand for rigor. I think this is true for Tyler, who has called proponents of pharma price controls “supervillains” and accused them of potentially “inducing millions of premature deaths”. Although he reserves the “supervillain” term for pharma price controllers consistently, plenty of other people are “villains” - for example, Gavin Newsom for excluding Tesla from a 4% electric vehicle rebate.

We all have our breaking points. For some of us, it’s when people kill millions of children. For others, it’s when they exclude cool companies from 4% electric vehicle rebates. Rather than accusing anyone who reaches a breaking point and uses harsh words of fanning terrorism, I think we should agree that it’s permissible to call someone a very bad person - even a villain! - but not permissible to engage in terrorism or assassination. The blame for the latter lies entirely with the terrorists/assassins, not with writers who criticize their target.

Even if Tyler disagrees with this, I think there are enough other people calling Donald Trump a bad person that it’s not worth his time to respond to me in particular; he should present some kind of more general explanation of his views.

(also, rumor says Trump has a Service to protect him from this sort of danger, although I’m not surprised Tyler doesn’t know about it - I hear it’s secret.)

More generally, I wonder if Scott ever has dealt with US AID or other multilaterals, or the world of NGOs, much of which surrounds Washington DC. I have lived in this milieu for almost forty years, and sometimes worked in it, from various sides including contractor. A lot of people have the common sense to realize that these institutions are pretty wasteful (not closedly tied to measured overhead btw), too oriented toward their own internal audiences, and also that the NGOs (as recipients, not donors) “capture” US AID to some extent. As an additional “am I understanding this issue correctly?” check, has Scott actually spoken to anyone involved in this process on the Trump administration side?

This has been a general pattern in debates with Tyler. I will criticize some very specific point he made, and he’ll challenge whether I am important enough to have standing to debate him. “Oh, have you been to 570 different countries? Have you eaten a burrito prepared by an Ethiopian camel farmer with under-recognized talent? Have you read 800 million books, then made a post about each one consisting of a randomly selected paragraph followed by the words ‘this really makes you think, for those of you paying attention’?”

I am not an expert on aid. But the development fellows and econ professors I mentioned above are, and they agree with my criticism. I ran this post by someone who’s worked closely with USAID and affiliated programs for a decade and they said they took my side. Not that it matters - the blogosphere, like the Royal Society, ought to be nullius in verba, not a chest-puffing competition of credentials but a data dump of receipts.

(although the expert I talked to also volunteered that they have never seen someone who has vast personal experience with and expertise in USAID refer to the program as “US AID” with a space, the way Tyler regularly does.)

And - fine - I admit I’ve never hob-nobbed with Trump administration officials. But I have delivered medicine in a Third World country. I’ve helped treat patients who were definitely going to die within a year, for want of medication that would be routine anywhere else. I’ve looked in parents’ eyes while telling them their kid wasn’t going to recover. It sucks. I can’t say that it teaches anything directly useful for understanding the details of the public charity funding landscape. Maybe everything I’m writing here about NICRA vs. overhead and sub-grants vs. sub-sub-grants is totally and embarrassingly wrong, and my lack of familiarity with DC NGO culture is to blame.

But - someone recently asked Elon Musk why he cancelled PEPFAR. Musk responded that what, huh, he didn’t know he cancelled PEPFAR, that must have been a mistake, somebody should get around to fixing it. If he’s telling the truth, maybe this redeems him a little? Certainly it makes him better than the ghouls cheering on its cancellation. But it doesn’t redeem him very much. I think if Elon had the same experiences I had, he wouldn’t have been able to sleep at night for fear that he had accidentally cancelled PEPFAR. He would have been calling his lieutenants at odd hours of the morning, all through the winter and early spring, saying “Hey, you definitely didn’t cancel the developing world medical funding, did you?” and the lieutenants would respond “Elon, you’ve asked me that four times tonight already, please stop obsessing over this.”

In the same way, I think if Tyler had the experiences I’ve had, he would not so casually write a handwavy four-line post vaguely insinuating slanders on USAID while protesting that he never quite said them clearly. If someone told him the post was misleading, he would care a lot about this, rather than acting like one of the most worth-worrying-about points was whether overly strong criticism of Trump might lead to his assassination. He wouldn’t be so breezy about a “radical clearing away of NGO relations”, or engage with the destruction of the charity ecosystem on the level of faux-profound slogans. Maybe Tyler is much nicer and more rational than I am and able to treat this whole situation with perfect Zen calm. But to me, it comes across as a sort of “missing mood” in the Bryan Caplan sense.

There are a bunch of other things wrong with Scott’s discussion of overhead, but it is not worth going through them all. I am all for keeping the very good public health programs, and yes I do know they involve NGO partners, and jettisoning a lot of the other accretions. That is the true humanitarian attitude, and it is time to recognize it as such. Better rhetoric, better thinking, and less anger are needed to get us there. It is now time for Scott to return to his usual high standards of argumentation and evidence.

Another missing mood! This has none of the intellectual curiosity that Tyler would apply to something he considered important. Just - there are “very good” programs and also “accretions”, USAID truly is a land of contrasts.

Here’s Congress’ chart of where USAID money goes:

“Humanitarian” is things like giving food to starving people. “Governance” is mostly grants to the government of Ukraine, which apparently “allowed the government to sustain its operations, helping pay state workers salaries and provide state services…[as the] economy shrank and budgets were redirected to the country’s defense”. The other categories should be self-evident.

Which of these are the “accretions”? If “Health” and “Humanitarian” are what Cowen is calling “very good public health programs”, and the Ukraine aid is probably controversial but everyone can understand why we’re doing it, what’s left?

I keep hearing about how most USAID money goes to rich woke snobs who use it to throw parties celebrating how much better they are than you. But where are these people? Are they hiding in the 6% overhead in Catholic Relief Services? The 3.9% overhead in JHPIEGO? The Ukrainians? The African clinics? I hear a lot about how USAID is funding foreign journalists to be really liberal, but it looks like all “democracy and human rights” grants combined - the category that this would fall into - are 2-5% of the budget (and this category also includes a lot of things like election observers).

The whole point of this debate is that (almost) everyone agrees “keep the good stuff, but jettison the bad stuff”. But the discussion is dominated by people who think USAID is 90% grift and operas about transgender people, and that the AIDS work is a tiny veneer on top of that to add credibility. My impression is that it’s the opposite. We can’t sensibly consider how to act on a policy of “keep the good stuff, but jettison the bad stuff” without a careful reckoning of who’s right, and whether the relevant instrument is a scalpel vs. a chainsaw.

This is why I found Tyler’s post saying that he was “fact checking” Marco Rubio’s claim that it was mostly waste, and indeed found that 75-90% “went to third-parties” and that “not all third parties are wasteful” but “USAID defenders [aren’t] keen to deal with such estimates” to provide such negative value. It looks like it’s offering this much-needed clarity, but in fact it’s the opposite.

In conclusion, I support keeping good stuff and jettisoning waste. If Tyler also supports this, then we’re on the same team. I continue to hope he will edit his original post to reflect this.