Mantic Monday 3/11/24

Robots of prediction, predictions of robots

Robots Of Prediction

Last month we talked about FutureSearch, a prediction startup that claims their AI is as good as experienced forecasters. This month, two academic teams claim to have gotten similar results with AIs of their own.

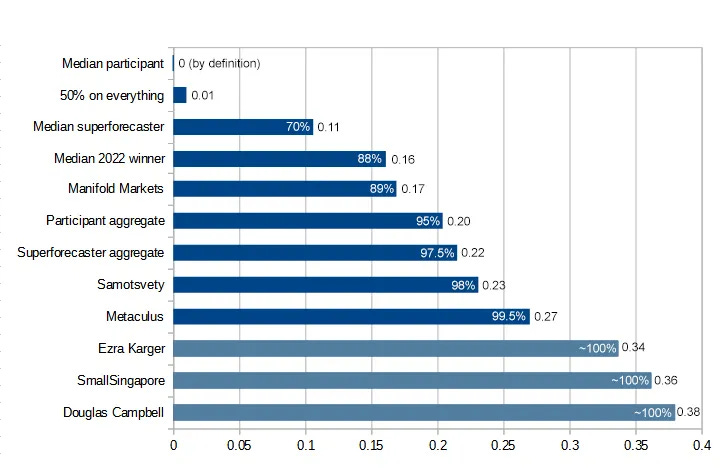

The first team is Halawi et al at Berkeley (also including Jacob Steinhardt, featured here before). They cite previous work on out-of-the-box AIs like GPT-4 or Claude. When these enter forecasting tournaments, they might beat some especially unskilled participants, but they lag behind the easiest aggregation method: “the wisdom of crowds”, ie a simple average of all forecasts. The wisdom of crowds is hard to beat - in my tournament, it scored at the 95th percentile.

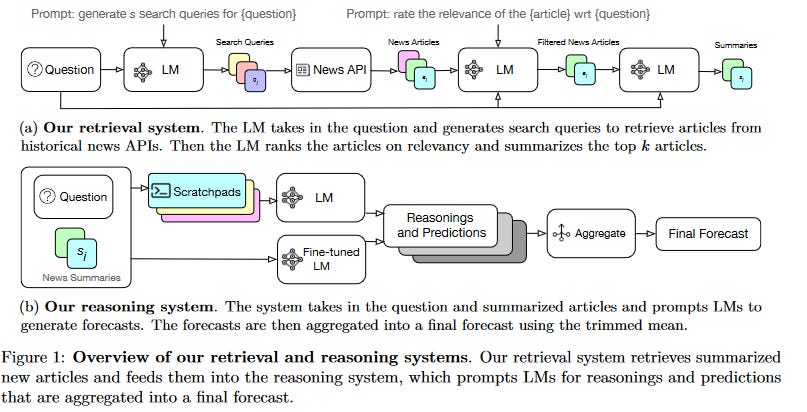

Halawi fine-tunes the out-of-the-box AI (in his case, a version of GPT-4) using some of the same tricks as FutureSearch. They attach it to “news APIs” (NewsCatcher, Google News) and teach it to search them effectively and reason about the contents.

In one part of the experiment, they use a human-written scratchpad to prompt the reasoning; in another, they fine-tune an AI on these scratchpads so it doesn’t need to use them every time. They get all these different AIs to make multiple predictions and average them together (wisdom of inner crowds - easier for AIs than humans since you can just raise the temperature!)

Then they fine-tune the whole system on forecasting questions from prediction sites (eg Metaculus, Manifold) that ended between mid-2023 and today. Why mid-2023? Because the AI was trained in mid-2023 and only knows what happened before then, and they can artificially limit its news API calls to before mid-2023. This lets them train the AI on thousands of forecasting questions without letting the AI cheat or having to wait years for the questions to resolve. They select the reasoning where the AI does well, and fine-tune it to do more stuff like that.

They find this works almost as well as the human crowd:

But the crowd still beats the AI, right? Halawi et al object that humans can forecast only when they feel like it - you can bet on a prediction market question you feel confident on, and avoid one you don’t. When they let their AI forecast only on those questions where it’s most likely to do well (eg those with lots of relevant news articles), it very slightly outperforms the human crowd.

As AI gets better, will it naturally beat humans in forecasting? Halawi et al say this won’t be trivial. They find a version of their system based off GPT-3.5 is only very slightly worse than the final version built off GPT-4. This suggests a forecasting AI built off GPT-5 or 6 might get only small improvements.

The second team is Tetlock et al. They start from the same place as Halawi - out-of-the-box LLMs aren’t good at forecasting. They’re more scathing about this than Halawi was - they argue that out-of-the-box models do worse than predicting 50% for everything (this was close to true of human forecasters in the ACX tournament).

Instead of increasing quality, Tetlock increases quantity. He wants to do wisdom of crowds, where the crowd is a bunch of different LLMs. So he gets twelve LLMs - including Bard, GPT, Claude, Mistral, PaLM, LLaMa, some Chinese models I’d never heard of, and a couple of variations on these bases - asks them to predict questions, and averages the results.

The results:

Next, we compare the LLM crowd performance to that of the human crowd for our second hypothesis, directly putting the two crowd-aggregation mechanisms head-to-head. To do this, we use the same LLM crowd average as before (taking the median LLM prediction on each question and averaging up the Brier scores across questions). We compare this to the average of median human predictions on the same questions. In our preregistered analysis, we fail to find statistically significant differences between the LLM crowd’s mean Brier score of M=0.20 (SD=0.12) and that of the human crowd, M=0.19 (SD=0.19), t(60) = 0.19, p = 0.850

Their study was much smaller than Halawi’s (31 questions vs. 3,672), so I don’t think this result (nonsignificant small difference) should be considered different from Halawi’s (significant small difference). Still, it’s weird, isn’t it? Halawi used a really complicated tower of prompts and APIs and fine-tunings, and Tetlock just got more LLMs, and they both did about the same.

I have two questions after reading these results:

Did they actually do the same, or is this just a function of the small sample size in Tetlock and the non-head-to-head comparison?

If you made Halawi-style system out of all twelve of the LLMs studied in Tetlock, and you wisdom-of-crowds-ed them together, would that do better than Halawi’s individual system?

I don’t know. I think you pretty quickly pick low-hanging fruit in LLM forecasting and get to a regime where new advances are just shaving off tiny fractions of a percentage point. But I look at the ACX tournament results:

Halawi and Tetlock’s AIs did between slightly-worse-than and equivalent-to the participant aggregate, so let’s say 90-95th percentile. FutureSearch claims to equal a 98th percentile forecaster, but they got this number through totally different and slightly suspicious methodology, so I don’t know if it’s actually any better.

Still, we see that Samotsvety is capable of 98%ile performance (likely real and repeatable) and Metaculus of 99.5th. So there’s still a long way to go before we exhaust the limits of what’s possible to predict given the available amount of information!

Towards Rationality Engines

An interlude, before we get to other interesting prediction news.

Forecasting AIs are pretty cool. I wouldn’t have expected them to work as well as they do. They are already superforecaster-level, and given the amount of low-hanging fruit that gets picked every day here, I can see them equalling or exceeding the top human forecasters in the next few years

But they can’t answer many of the questions we care about most - questions that aren’t about prediction. Do masks prevent COVID transmission? Was OJ guilty? Did global warming contribute to the California superdrought? What caused the opioid crisis? Is social media bad for children?

I see two interesting challenges ahead here:

Making an AI that can do this.

Proving/testing that an AI can do this

1 . . . might be easy? The forecasting AIs - again, it took various professors and geniuses to make them, I don’t want to call them absolutely easy - but by the standards of AIs, they seemed pretty basic. Just get a normal AI and teach it a few forecasting tricks. It’s not obvious that forecasting AIs aren’t already full domain-general rationality engines.

(an example: I’ve been following the lab leak debate, and recently saw someone say the prior for any given pandemic being a lab leak - ie not counting anything specific we know about COVID - is 20%. I realized I could trick FutureSearch into double-checking this number by asking for the probability that the next pandemic is a lab leak. It said 15%, which was gratifyingly close. All we need is an AI that can answer questions like this without you having to trick it first!)

How would we improve forecasting AIs’ ability to answer non-forecasting rationality questions? This shades into the question of how we would test success - we need more structured data. Forecasting is perfect here - you can train an AI on thousands of question/known-correct-answer pairs. What else is like this?

Maybe trials? Maybe someone has a database of thousands of criminal trials, and the jury’s verdict? Even better would be a set of trials where DNA evidence or something later provided a gold standard, just in case the jury was wrong. Maybe other kinds of legal cases, like constitutional arguments where the Supreme Court ruled 9-0 one way or another?

Maybe scientific papers? Maybe you could put in the Introduction section and train the AI to predict the results? You would want to really carefully filter for scientific papers that were actually good, and this isn’t quite the same thing as rationality per se, but it might work?

If you got 10,000 forecasting questions, 10,000 trials, 10,000 constitutional law cases, and 10,000 scientific papers, trained an AI to do well on half of them, then kept the other half as a validation set, would it just learn each of those four domains separately? Or would it start becoming a domain-general reasoner?

One of the limitations of existing LLMs is that they hate answering controversial questions. They either say it’s impossible to know, or they give the most politically-correct answer. This is disappointing and unworthy of true AI. I don’t know if simple scaling will automatically provide a way forward. But someone could try building one.

The Predicting Of Robots

The story so far: the Forecasting Research Institute wanted to see if superforecasters could sort out this whole AI thing. Their forecasters averaged an 0.4% chance AI would destroy humanity by 2100. When they learned domain experts thought it was higher, they didn’t care, and stuck with 0.4% chance.

The most pessimistic domain experts were pretty annoyed by this, and challenged FRI’s research. Maybe AI is an especially tough subject to understand. Maybe if you forced the superforecasters to do really deep dives and hear all the arguments and become domain experts themselves, they would change their minds.

So FRI gathered eleven of the most AI-skeptical superforecasters (average probability of AI doom: 0.1%) and another 11 very concerned AI safety experts (average probability: 25%) and made them spend forever talking and thinking about it. The average skeptical superforecaster spent 80 hours on the project, including research, talking to experts, and arguing with the more concerned people.

After 80 hours, the skeptical superforecasters increased their probability of existential risk from AI! All the way from 0.1% to . . . 0.12%.

(the concerned group also went down a little, from 25% → 20%, but the paper stresses this wasn’t necessarily because of the experiment; several people in this group attributed it to unrelated policy victories during this period)

Okay, so maybe this experiment was not a resounding success. What happened?

Did the two sides just fail to understand each other’s arguments? No. They argued with each other for 80 hours, and were able to (when asked), give excellent summaries of the others’ key points. So there must be some more fundamental problem.

Did they pick defective concerned experts? Tentatively no. The IRB says it’s “important” “for” “privacy” “reasons” not to reveal who the experts were, but the paper says they were selected by Open Philanthropy Project, a big AI safety funder who I trust a lot and who I would expect to choose good people (Eliezer Yudkowsky, who is less sanguine about OpenPhil than I am, does sort of blame this one).

Did the skeptics underestimate the blindingly-fast speed of current AI research? Seems like no. Both groups had pretty similar expectations for how things would play out over the next decade, although the concerned group was a little more likely to expect detection of some signs of proto-power-seeking behavior.

As far as I can tell, the biggest difference was about speed. The skeptics expected a relatively leisurely progress through the human level, with the last few human tasks in the long tail taking forever to fall. Both groups expected approximately human-level AI before 2100, but the concerned group interpreted this as “at least human, probably superintelligent”, and the skeptics as “it’ll probably be close to human but not quite able to capture everything”. When asked when the set of AIs would become more powerful than the set of humans (the question was ambiguous but doesn’t seem to require takeover; powerful servants would still count), the concerned group said 2045; the skeptics said 2450. They argued that even if AI was smart, it might not be good at manipulating the physical world, or humans might just choose not to deploy it (either for safety or economic reasons).

The best that FRI could do in terms of real disagreement was to say that the concerned group expected things to happen very fast, the skeptics slowly. There’s a transhumanist meme:

…that probably encapsulates as well as anything the spirit of what the concerned group seems to believe that the skeptics don’t.

I found this really interesting because the skeptics’ case for doubt is so different from my own. The main reason I’m 20% and not 100% p(doom) is that I think AIs might become power-seeking only very gradually, in a way that gives us plenty of chances to figure out alignment along the way (or at least pick up some AI allies against the first dangerous ones). If you asked me for my probability that humans are still collectively more powerful/important than all AIs in 2450, I’d get confused and say “You mean, like, there was WWIII and we’re all living in caves and the only AI is a Mistral instance on the smartphone of some billionaire in a bomb shelter in New Zealand?”

So what do we do with this?

One thing we could do is say “Okay, good, the superforecasters say no AI risk, guess there’s no AI risk.” I updated down on this last time they got this result and I’m not going to keep updating on every new study, but I also want to discuss some particular thoughts.

I know many other superforecasters (conservatively: 10, but probably many more) who are very concerned about AI risk (example: Samotsvety). Is this just cherry-picking? Could we find 10+ superforecasters who believe anything? Or is this question unusual in its bimodal distribution of superforecaster opinions?

If it’s unusual, can we find other questions like this? What do they have in common? Does plowing through the disagreement and taking the median anyway usually work in questions like this? How often does it work?

Are superforecasters all the same religion (or no religion)? If not, do the religious ones believe in the Judgment Day? If so, that’s a weird bimodal split in superforecasters about a future event, isn’t it? This is only sort of a joke - if it’s true, religion will be some kind of special domain that superforecasters’ expertise can’t pierce. What other special domains are like this?

This ties back to the “rationality engine” section above - is forecasting a single domain-general skill? Or is it excellence at predicting a certain type of near-term geopolitical event, such that superforecaster performance regresses toward the mean on other types of tasks?

This Month In The Markets

There’s been more news and claims about the LK-99 alleged superconductor recently, all of which have totally failed to move the market away from 4%:

When the OpenAI board tried to fire Sam Altman last year and everyone said they were making a crazy mistake, I urged patience, saying maybe there was some kind of good plan. With the appointment of a new board, the last few loose ends from the affair have now been settled, and - I was wrong. There was no good plan and it was a giant self-own, sorry. The new board is back to having Sam Altman, plus random businesspeople who I don’t expect to have good opinions or exercise real restraint. Accordingly, the prediction market about whether anything good will come of it has gone down from its already low levels:

Hadn’t been following this much, but good to have a number on it:

I guess I have to post this one every month until November:

I guess this one too:

Tim Scott leading the (Manifold) race to be Trump’s VP, I think this could make for some interesting crossed ideological wires:

Israeli operations in Gaza not expected to end until autumn (!)

Crypto is back in the news, with Bitcoin at record highs again. Polymarket is crypto-based, so it shouldn’t be surprising that they have the highest-liquidity and most diverse crypto questions:

And Futuur has an Infectious Diseases section I hadn’t seen before:

Okay, I admit I forgot Futuur existed until this moment. But now I’m looking at their play money markets, and some of them have 3,000+ participants? What?!

Short Links

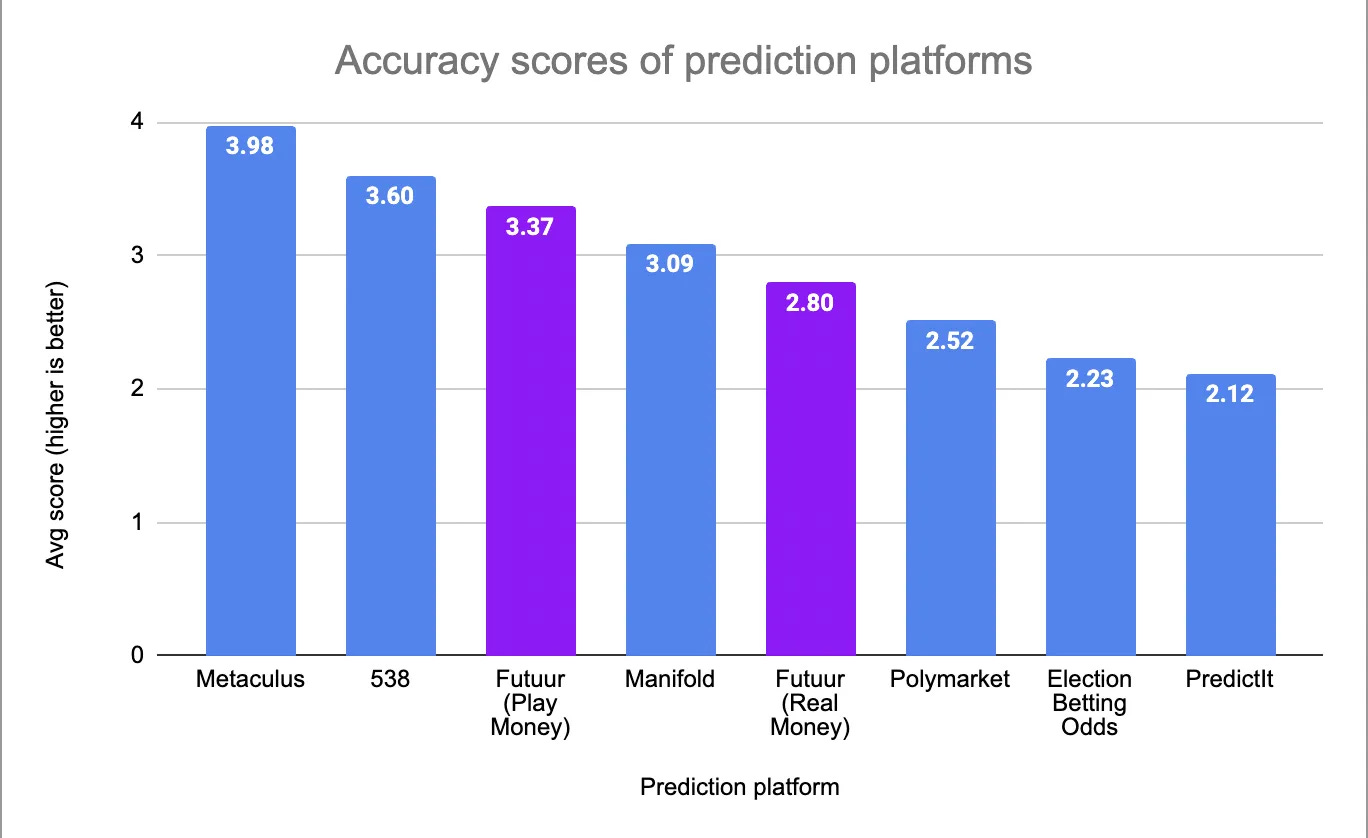

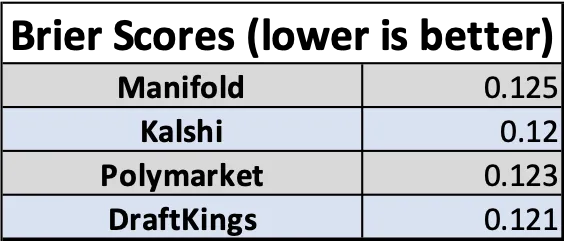

1: Apparently, forgetting that Futuur exists is a common problem! Jeremiah Johnson’s Asterisk article Do Prediction Markets Have An Election Problem? (featured here two months ago) also didn’t have Futuur. The folks at Futuur, who did not forget that they existed, added themselves to Johnson’s results and find that they actually did quite well, with the play money half outperforming the real money half.:

2: Mike Saint-Antoine compares forecasting platforms on the Oscars:

More at the link; see especially the last section “Mike this is a boring result, why the heck are you even making this post?”

3: Satori is some kind of crypto thing that claims to be “predicting the future with decentralized AI”. I can’t make heads or tails of it and I’m slightly concerned it’s just a lot of buzzwords strung together, but it does have a white paper. Someone tell me if it makes sense to them.

4: Also in crypto: Sam Altman’s WorldCoin has quadrupled in value this month. Some of this is the general crypto rally, but it also seems to go up whenever OpenAI does something cool, suggesting it’s more of a “how popular is Sam Altman and his company right now” memecoin than anything else. This ties back to some of our old discussion on using memecoins to track people and companies that can’t or won’t sell you real stocks. This isn’t investment advice, but WorldCoin might be in some sense a shadow OpenAI stock right now.