In The Long Run, We're All Dad

...

I.

In February 2023 I found myself in the waiting room of a San Francisco fertility clinic, holding a cup of my own semen.

The Bible tells the story of Onan, son of Judah. Onan’s brother died. Tradition dictated that Onan should impregnate his brother’s wife, ensuring that his brother’s line would (in some sense) live on. Onan refused, instead “spilling the seed on the ground”. God smote Onan, starting a 4,000-year-old tradition of religious people getting angry about wasting sperm on anything other than procreative sex.

Modern academics have a perfectly reasonable explanation for all of this. If Onan had impregnated his brother’s wife, the resulting child would have been the heir to the family fortune. Onan refused so he could keep the fortune for himself and his descendants. So the sin of Onan was greed, not masturbation. All that stuff in the Talmud about how the hands of masturbators should be cut off, or how masturbation helped cause Noah’s Flood (really! Sanhedrin 108b!) is just a coincidence. God hates greed, just like us.

Modern academics are great, but trusting them feels somehow too convenient. So there in the waiting room, I tried to put myself in the mindset of the rabbis thousands of years ago who thought wasting semen was a such a dire offense.

The average ejaculation contains about 300 million sperm. There are about 300 million people in the United States. If every sperm in a single ejaculation got to fertilize an egg and incubate in a womb, it would be enough to populate a second America.

America has about 200 living Nobel Prize winners. 735 billionaires. 1,000,000 doctors, 5,000,000 nurses. 100,000 pilots, 700,000 cops. Also 700,000 drug dealers, 100,000 murderers, and 1,700 NYT journalists.

That doesn’t necessarily mean my cup contained exactly 100,000 future pilots. If we assume complete genetic determinism, my sperm form a normal distribution around my personal genetic average. I’m terrible at three dimensional reasoning, so let’s say I’m two standard deviations less likely than usual to become a pilot. If my wife is normal on this trait, and we average it out, that means only about 32,000 future pilots in the cup.

On the other hand, I’m better than average at writing. I might be among the top 20,000 most-read authors in the US, so maybe +4SD above average. Again assuming my wife is normal, that suggests even the average kid we have will be a good writer. But imagine an entire America worth of people centered around being a good writer. The best writer in existing America should be +6SD above average; the best writer among the sperm in the cup is +8SD. 8SD is “best in two quadrillion”. There has never been a writer that good in the whole history of the world. There is a sperm in that cup who could write at an utterly superhuman level, write things none of us could possibly imagine, things so good it’s not even clear you would still call them writing and not some entirely new semi-divine form of art.

There’s also, on priors, some sperm who would shoot up a school. There’s a decent chance of a few who, if given an egg and a womb, would destroy the world, and a few others who would save it. A few hundred might ruin my life so thoroughly that I would commit suicide to escape them. A few dozen might be so great that people would build statues to me just for being their father, the same way some people build statues to St. Joseph.

The nurse called my name, I handed her the cup, and she took it away to pour into some lab apparatus. Good bye, 200 Nobelists. Good bye, 32,000 pilots. Good bye, son who would have destroyed the world. Good bye, daughter who would have saved it. I waited to see if God would smite me. He did not. A few weeks later the clinic called and said there was nothing wrong with my sperm. My fertility problems were just bad luck. I should just keep trying.

There’s an old Jewish joke. How do you make God laugh? Tell Him your plans. 1/10,000 chance of a pilot, because I’m bad at navigation and the base rates are low. 1/10 chance of a doctor, because of all the doctors in my family. I knew it was bogus. Partly because I’m bad at standard deviations and probably got the numbers wrong. But partly because anything can happen. Maybe I was having all this trouble because the lab missed something and I really was infertile. Maybe my wife was infertile. Maybe we’d eaten too many microplastics and it was all over. Maybe we’d have a kid, an amazing kid who could have changed everything, but the world would end in 2027 and they’d never get a chance. Still, you’ve got to calculate. One in three million chance of becoming a billionaire. One in thirty thousand chance of committing murder. One out of this. One in that. One one one one one, until you reach semantic satiation on the number “one” and the syllable loses all meaning.

This time God chose to frustrate my calculations even faster and more decisively than usual: He blessed me with twins.

II.

Natural selection didn’t design the female body to carry two children. It barely, grudgingly, designed it to carry one. Two is a cruel joke.

I remember cutting an onion, sometime during month one. My wife asked if they were a different variant from usual, or if they’d gone bad. They hadn’t. It had to be morning sickness. We laughed and hugged each other. This pregnancy thing was starting to feel real!

A month later - including a hunt through the kitchen to cleanse it of any shred of onion, or anything that had ever touched an onion - we agreed that actually, morning sickness was bad. Two months later, we debated bringing my wife to the ER because she hadn’t eaten anything other than plain saltine crackers in several days. We did manage to avoid the hospital, but it was rough. I’m surprised more people don’t name their children after Zofran®. Women get such positive feelings about it, right when they’re considering baby names. For a girl, you could nickname her Zoe. For a boy, Frank.

And after the morning sickness it was asthma. After the asthma, anemia. After the anemia, hip pain, trouble sleeping, trouble walking, trouble with everything.

I’ve heard rumors of some women who keep working all through pregnancy, with a smile on their face. Pronatalist influencer Simone Collins says she was taking business calls from her hospital room during the delivery. I think it’s a conspiracy. All the pronatalist influencers get together and say that pregnancy isn’t so bad. Young women believe them, and so the human race survives another generation.

As my wife labored to build our childrens’ physical forms, I toiled to give them their spiritual-semiotic identity. The theory of nominative determinism posits that a person’s name shapes the course of their future life. Its proponents have collected a mountain of evidence: British chief justice Igor Judge, neurologist Lord Brain, poker champion Chris Moneymaker, investment CEO Eugene Profit. The Chinese think the number of strokes in the characters that form a child’s name must add up to a lucky number; the Jews believe each letter corresponds to a number, and a person’s name resonates spiritually with all other words whose letters sum to the same amount.

Now the statisticians have joined the fray: did you know that children with short first names earn over $10,000 more than longer ones? Or that men named "Jim" make 50% more than men named "Isaiah"? Is this causation or confounding? Names indicate whether you are black or white, rich or poor, and whether your parents are traditional or eccentric; what is left after adjusting for this effect? The only paper I’ve seen even begin to address the question is a sibling-control study by David Figlio, who finds that even within families, children with lower-class names perform worse. And you don’t need scientists to know that names affect how other people see you. Just ask Chad, Karen, Tyrone, or the poor doctor I worked with once named Osama (he went by “Sam”).

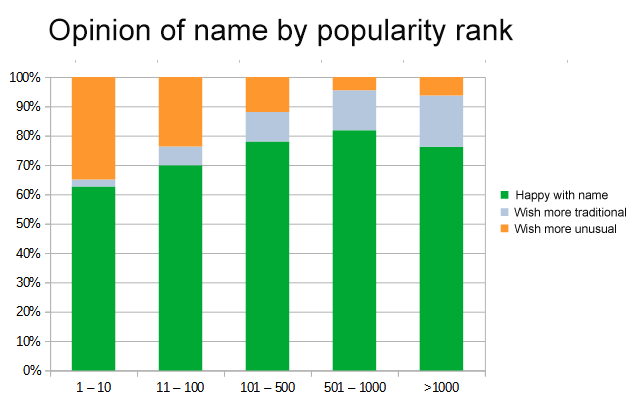

But also, some people love their names, and other people hate theirs. This was the factor I was least sure about, so I surveyed 1518 blog readers.

Here “popularity rank” comes from the List Of Most Popular Baby Names for the respondent’s birth year - for example, Scott was the 39th most popular boys’ name in 1984, so I am rank 39. I find that people are happiest with names in the 501 - 1000 range (a separate question, which asked people to rate their happiness with their name on a scale of 1 - 5 without reference to whether it was traditional or unusual, got the same result).

What about other considerations?

I asked people how happy they would be with ten different types of names.

People expressed a strong preference for common older names like John and Mary. Does this contradict the finding above that people with very common names were least happy? Not necessarily - the common names on the question above included all common names (the #1 most common name for boys born last year is “Liam”), so maybe people like common older names in particular? But I looked at people in the sample named John, Michael, Mary, and Sarah, and they didn’t differ much from the overall common names category. So people may think they would like names like these, but actual Johns and Marys wish they were named something a little more unusual.

The least popular categories included “new-fangled name” and “sci-fi / fantasy name”. The most popular were “name honoring a deceased relative”, “name from your ethnic origin”, and “historical figure”.

So that’s why I decided to name my children Napoleon Herschel Siskind and Hatshepsut Tzeitel Siskind.

No, seriously, I’m not comfortable telling the Internet my kids’ names. I’ll let them get doxxed the usual way - by the NYT, the first time they express a problematic opinion.

But I need some way to refer to them online, so their nicknames are Kai and Lyra.

III.

On December 13, 2023, two surprisal-minimization engines registered an unpredecented spike in surprisal. They were thrust from a sunless sea into a blooming buzzing confusion, flooded with inexplicable data through input channels they didn’t even know they had. The engines heroically tested hyperprior after hyperprior to compress the data into something predictable. Certain patterns quickly emerged. Probability distributions resolved into solid objects. The highest-resolution input channel snapped into place as a two-dimensional surface being projected onto by a three dimensional space. But - a blur of calculations - the three-dimensional nature of space implies that it must be intractably large! And if there are n solid objects in the world, that implies the number of object-object interactions increases as n(n-1)/2, which would quickly become impossible to track. Their hearts sinking, the engines started to worry it might take hours before they were fully able to predict every aspect of this new environment. A panic reflex they didn’t know they had kicked in, and they began to cry.

Some outside force picked them up, rocked them back and forth. A million inexplicable sense-data, overwhelmed by a single stimulus - a rhythmic stimulus. The predictability of importance-weighted sense-data shot way up! Kullback-Leibler divergence dropped to near-zero! The panic reflex subsided, and the engines - exhausted by their sudden spurt of computation - shut off to renormalize synaptic weights.

Soon the engines will discover that things are even worse than they think. Some of their predictions are hard-coded; they will never be able to change them to match the world. Their only hope is to change the world to match their predictions: they are obligate agents. As they grow older, their goal systems will throw up increasingly complicated hard-coded forecasts; food, water, belonging, social status, sex. Their only path towards predictive accuracy will be to obtain all of these things from a hostile world. It’s a lousy deal.

My poor, fragile, little cognitive engines! These, then, will be the twin imperatives of your life: surprisal minimization and active inference. If your brains are still too small to process such esoteric terms, there are others available. Your father’s ancestors called them Torah and tikkun olam; your mother’s ancestors called them Truth and Beauty; your current social sphere calls them Rationality and Effective Altruism. You will learn other names, too: no perspective can exhaust their infinite complexity. Whatever you call them, your lives will be spent in their service, pursuing them even unto that far-off and maybe-mythical point where they blur into One.

If you pursue them only far enough to reduce your own predictive error, it will still be a life well-lived, and nobody will blame you for it. But if you choose, you can take an extra burden upon yourself, improving not just your own models but the broader predictions of the world. You can push forward the frontiers of knowledge, or improve the lot of all humankind. It’s a crazy thing to try, when even your own local predictions are so far from perfect accuracy. I cannot exactly tell you why you should want to do something like this. If you feel it, you feel it; if not, so it goes.

But a parable: when you were born, your mother kissed you. Along with the kiss came a microdose of the BCS3-L1 genetically engineered bacterium. Without any teeth to cling to, it fell into the pit of your stomach and died. But she’ll kiss you again and again, transferring a few more BCS3-LI each time. In a few months, one of the colonists will find an incipient tooth and hang on for dear life. It will fight off competitors, wage epic battles that will determine the fate of the mouth for decades to come. It will win, because its genetic enhancements are pretty good. Then, if some smart people got their calculations right, it will do exactly nothing. No tooth decay. No cavities. The teeth will stay safe and clean.

When you get older, I’ll tell you the story behind this. Your mother worked for a company synthesizing genetically engineered tooth bacteria that prevent cavities. She isn’t the kind of person who would push a product on others that she hadn’t tried herself. So she infected herself with the bacterium, fresh out of the lab. Other people in the company did the same. But only she was pregnant. Babies get their mouth bacteria from their mothers. So you might be the first children in the world to grow up without s-mutans-mediated tooth decay.

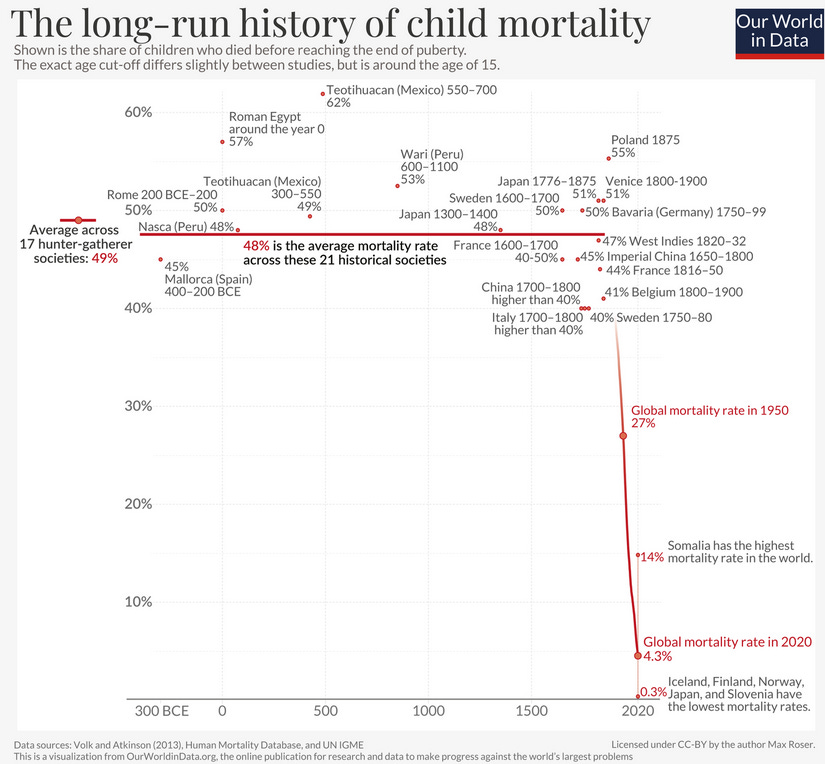

Tooth decay isn’t the worst thing in the world. As victories go, this is a relatively minor one. I tell it to you only because it is ours. Our drop of water in a vast ocean of victories that have improved the lot of humankind on every continent, for as long as the species lasts. There is nothing that hammers this in like being a new father - nothing like seeing two tiny rudimentary week-old cognitive engines struggle not to fade into the entropic background. Kai, you wouldn’t come out of your mother on your own - the obstetrician used vacuum extraction to save your life. Neither of you was a great breastfeeder at first, and if we hadn’t had nurses and bottles and formula, you might not have made it. A few days after your birth, it rained two inches in fifty degree weather; if we didn’t have central heating and space heaters and warm blankets, who knows what would have happened? In 1800, about 50% of babies died before their fifth birthday. This statistic used to feel like a brute fact. Now I’m noticing all the little cracks that Death could creep in through, if we didn’t have our cornucopia of technologies and our team of vigilant pediatricians.

There are two of you. Back in 1800, statistically, one of you would have made it. I look at you now - such beautiful, fragile cognitive engines - and I cannot bear the thought of losing either one. The statistics for the 21st century suggest I won’t have to.

I was thinking about this recently, because - well, I feel kind of bad. I instantiated two surprisal-minimization engines - two conscious algorithms designed to feel negative qualia in the presence of hard-to-predict stimuli - on a world ruled by 195 mutually-hostile and frequently-shifting coalitions of over-evolved murder-monkeys, many of whom have nuclear weapons. I cannot quite remember why I thought this would be a good idea. I blame the pronatalist influencer conspiracy.

But if I have any excuse at all, it’s excessive enthusiasm for this grand project of world-scale surprise minimization and active inference. You are here to benefit from it, to enjoy sensual and intellectual pleasures that our ancestors could never know. And also, if you choose, to continue it, push it forward into a new era. You have already contributed in a tiny way - as guinea pigs - to the conquest of tooth decay. But there are so many other worse sources of prediction error out there. What else might you conquer, my two little surprisal-minimization engines?

IV.

There is a secret known only to parents of twins, medical residents, and Alexey Guzey: the human body does not actually need sleep. After 31 hours awake, you get an integer overflow in God’s database and go back to being well-rested again. Also you gain the ability to see angels.

This has become the new rhythm of our lives. Changing, nursing, burping, first one child, then the other. Twenty minutes per child, times two children, times once every 2-3 hours; you can do the math. We do everything else - laundry, shopping, cooking, occasionally even napping - in the precious intervals when both babies are asleep.

The Snoo is a $1500 computerized bassinet that continually assesses babies’ needs and tries to calm them with various soothing noises and automated rocking motions. We got two, both of which have been soundly rejected. The twins insist on sleeping in their carseats, which we’ve grudgingly moved to the nursery. At first I was miffed, but now I see their logic. You’ve got to learn to resist the algorithmic content mills early.

Kai has some baby version of Alien Hand Syndrome. His arms are controlled by a malevolent entity with a grudge against the rest of his body. If we leave them loose, they wave wildly in all directions, and he freaks out. This is apparently a common problem, best solved by heavy swaddling clothes. The malevolent entity struggles against the swaddle and occasionally breaks free, like some 1980s horror movie monster. Every nursing, we must struggle against it and bind it anew before returning him to his carseat.

Lyra is already an overachiever. She has clearly read all the How To Be A Baby textbooks, learned when crying is appropriate, and only cries at those specific times. She drinks the exact amount of milk recommended on the Baby Age-Appropriate Nursing Chart, then refuses to accept more. I’m worried that if we don’t teach her to think independently soon, she’ll end up somewhere terrible like Harvard.

I look over at them. They seem so peaceful in their stupid carseats. Let them sleep. Let them nurse as often as they want. They’ll need all their strength for what’s ahead.

Kai. Lyra. You’ll live to see a million things that man was never meant to see. You were born just in time for a high-speed collision with the hinge of history. I’m only 39, I expect to be around when whatever-it-is happens - but if not, you’re our family’s ambassadors to the singularity. A thousand generations, from hardy Neolithic farmers to studious Russian rabbis to overprivileged American office workers - they all lived and died so you could be here and experience this, and maybe tilt the course of what’s coming by a couple of micro-degrees.

Parents are supposed to teach their children the skills they need to navigate the world. This already feels somewhat obsolete - where are the Google programmers who were taught Python by their fathers, or the Instagram influencers who learned content creation on their mother’s knee? Soon it will be completely hopeless. Where we’re going there are no roads. You’ll have to figure it out by yourself. If I am to pass on anything of value to you, it can only be the ultimate power, the technique that forms all other techniques.

I’ve always wondered why I wrote so much. Now I realize I was leaving you bread crumbs.

Happy holidays, from our family to yours. ACX will return to its normal posting schedule in January.

…of 2042.