How Are The Gay Younger Brothers Doing?

...

In the 1990s, Blanchard and Bogaert proposed the Fraternal Birth Order Effect (FBOE). Men with more older brothers were more likely to be gay. “The odds of having a gay son increase from approximately 2% for the first born son, to 3% for the second, 5% for the third and so on”.

This started as a purely empirical finding. If you surveyed enough men, you would find it was true, even though no one knew why1. In 2006, Bogaert found that the effect applied only to biological siblings and not adoptive ones, suggesting a biological cause. He proposed a mechanism based on H-Y antigens, a set of molecules on male cells involved in sexual development. If a mother has many male pregnancies, her immune system might become gradually more sensitized to H-Ys, start attacking them, and interfere with later fetuses’ sexual development.

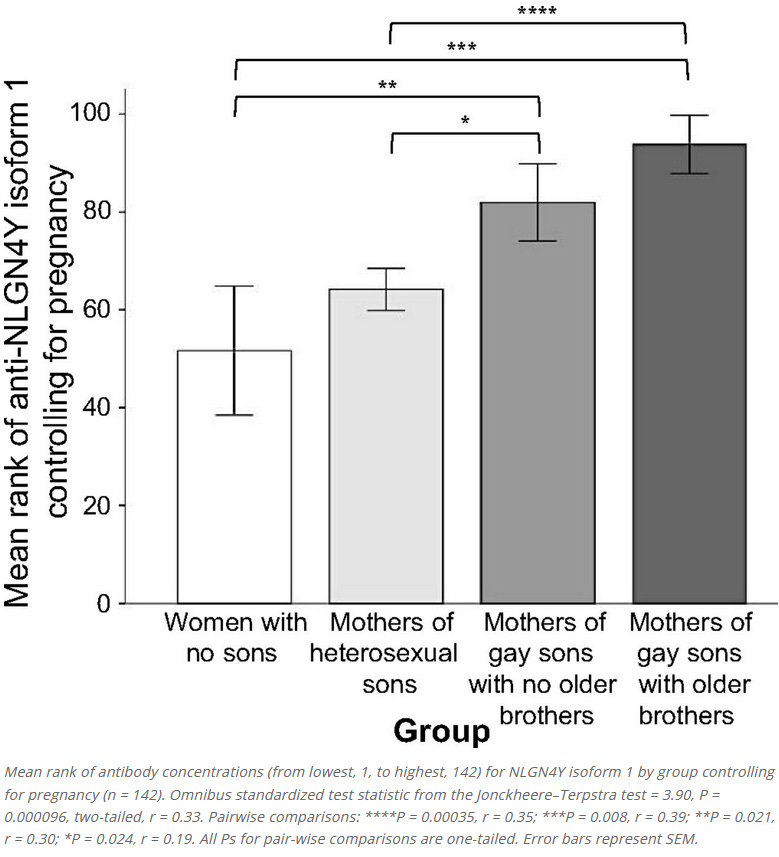

In 2018, scientists announced tentative confirmation: antibodies to a male protein called NLGN4Y seemed more common in the mothers of gay sons than in men, non-mothers, and mothers of straight people.

It seemed like the FBOE was ready to coast into the pantheon of accepted scientific ideas.

But three more recent studies have complicated things, starting with:

Frisch, Hviid, And 2,000,000 Danes

Not actually that recent (2006), but still relevant.

Denmark legalized gay marriage in 1989 and keeps great records. So a sufficiently bold scientist could get data on everybody in Denmark, use birth certificates to figure their family structure, use marriage certificates (gay vs. straight) to figure out their sexual orientation, and study the determinants of homosexuality with a sample hundreds of times bigger than anyone had done before.

Frisch and Hviid tried this and discovered many interesting things2, but not a clear fraternal birth order effect.

They argued that previous studies of the FBOE hypothesis had used pretty atypical gays - often pedophiles or people in therapy, because these were the populations hanging around scientists and easy to organize into a sample to study. Gays who get gay-married is also a selected population, but probably a more typical one, and studying them showed nothing.

Ray Blanchard, leading proponent of FBOE, wrote a comment in response suggesting that maybe an alternative method did end up finding a small but real difference. But Frisch and Hviid wrote a counter-counter-response saying even this small difference was artifactual and should be ignored.

So it seems that the largest, best study failed to find the FBOE. But then how come so many previous studies did find it?

Vilsmeier et al: Statistics Is Hard

Vilsmeier, Kossmeier, Voracek, and Tran have opinions on this.

The paper is 25,000 words of very dense statistical reasoning; I often found myself struggling to read a paragraph, only to eventually realize it was saying something obvious in as many long words as possible. But in the end I see it as making a few main points:

Blanchard and Bogaert weren’t justified in saying that older brothers but not older sisters increased chance of homosexuality. In their original paper, they found that the coefficient on older brothers was significant, and that on older sisters wasn’t. But the difference between “significant” and “nonsignificant” is not itself statistically significant. So we need to re-evaluate whether the theory should actually apply to brothers, brothers and sisters, or neither.

And in fact their statistics can’t really do that! Birth order statistics are hard: you want to isolate an effect (birth order) from a separate but related effect (family size). For example, you might guess that gays would have fewer siblings overall than straights (because their parents had some gay genes, and so weren’t as committed to the heterosexual-sex-for-reproduction thing). So if the FBOE is true, there will be one effect giving gays fewer siblings, plus a contrary effect giving gays more siblings. In theory you can separate these out by looking at birth order and older brothers vs. sisters and then controlling for family size. In practice, B&B slightly bungled this, and it’s impossible to tell from any of their statistics if gays have more older brothers, older sisters, or just older siblings in general. Read “Part i. current approaches do not quantify the theoretical estimand of interest: insights from probability calculus” for the details.

Having noticed these flaws, they meta-meta-analyze all previous meta-analyses on this subject with much more advanced and accurate statistical tools, and find:

Depending on which specific study set is interpreted, the odds for observing an older brother among the set of all older siblings reported by homosexual participants (male or female) were between 7% (for the Women full set) and 17% (for the 31 samples included in Blanchard 2018a) greater than those same odds for the heterosexual participants. However, the 95% CIs suggest that these estimates were compatible with a 6% decrease as well as with a 35% increase (i.e., the respective lower and upper bounds of the 95% CI of the summary estimate for the six probability samples included in Blanchard 2018a) for these odds.

In other words, while their point estimate somewhat supported the hypothesis, confidence intervals included zero3.

Note that this is just saying there is a small to zero effect for “observing an older brother among the set of all older siblings”. It doesn’t argue against versions of the FBOE that say the main difference between gays and straights is more older siblings in general (although AFAIK nobody has ever supported this hypothesis).

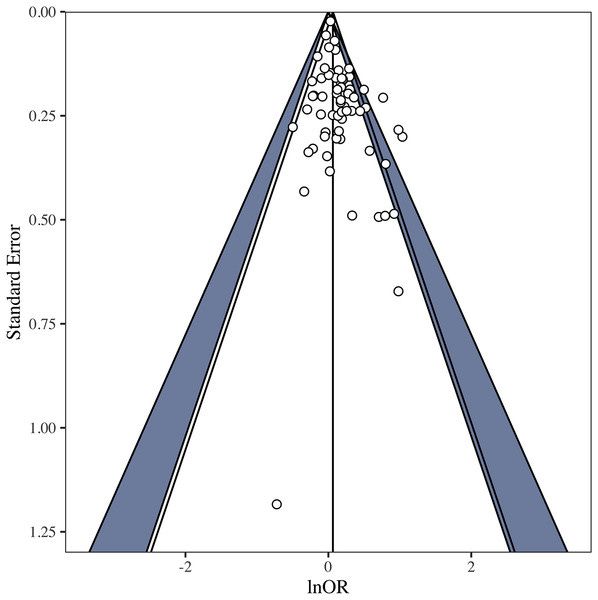

Fourth, they found some evidence of publication bias:

…suggesting that even the nonsignificant effect they found might have just been from small studies and a file drawer effect.

So they’re claiming FBOE doesn’t exist, right? Actually, their paper is so long and dense I can’t figure out exactly what they’re claiming. It sort of looks like they think that, but when someone says so, they protest that:

Blanchard & Skorska (2022) completely misconstrued our work by claiming that we wrote there is no evidence for the FBOE in men or women. This is not what we claim, neither in the present study, nor in the preprint.

So what are they claiming?

I’m not sure, but notice that their specification of the effect only demonstrates that older brothers do not cause homosexuality too much more than older sisters. If both types of older sibling caused homosexuality, that would match their findings, even if brothers caused it slightly more.

And in fact, hot on their heels, a new study found exactly that!

Ablaza, Kabatek, Perales, And 9,000,000 Dutch People To The Rescue

Remember how Frisch and Hviid managed to look at two million Danes? Well, the Dutch also have gay marriage and keep really good records. Ablaza, Kabatek, and Perales were able to obtain and analyze the data from nine million of them. They do more advanced statistics than any of their predecessors and are able to report basically every parameter of interest with high confidence4.

They find:

On average, individuals who did not enter a same-sex union have 2.36 siblings. This number is split evenly between younger (μ=1.19) and older (μ=1.17) siblings. The average sibling sex ratio—that is, the number of brothers over the number of sisters—is 1.04 for both younger and older siblings. In contrast, individuals who entered a same-sex union have fewer siblings (μ=2.14) and a greater number of older (μ=1.23) than younger (μ=0.91) siblings. Further, the sex ratio of their older siblings is skewed towards brothers (μ=1.18). All of these differences are statistically significant . . . these patterns manifest among both men and women.

These effects are potentially large:

For example, 0.73% of men who are the youngest of five siblings entered a same sex union, compared to just 0.35% of men who are the eldest of five siblings . . . the share of men with four older brothers entering a same-sex union is 0.96%, more than twice the share among men with four older sisters (0.46%)

Because of their advanced regression model, they’re able to tease apart family size effects from birth order and gender effects:

Adding one younger sister to an existing sibship is associated with a 13.8% decrease in the probability of entering a same-sex union (OR = 0.87, p < 0.001)5; moving one place down the birth order while keeping the number of younger and older brothers fixed is associated with an 7.9% increase in the probability of entering a same-sex union (OR = 1.08, p < 0.001); and replacing one older sister by one older brother is associated with a 12.5% increase in the probability of entering a same-sex union (OR = 1.13, p < 0.001). Replacing one younger sister by one younger brother is associated with a 1.2% increase in the probability of entering a same-sex union (OR = 1.01), but this estimate is not statistically significant (p > 0.1).

Also:

To illustrate the combined effects of birth order and sibling sex, we use the model to predict and plot the probabilities of entering a same-sex union for individuals in all relevant permutations of two-person sibships (Figure 3). In this example, we focus on two-person sibships because they are the most common sibship type (35% of individuals) and because the corresponding number of permutations is fairly contained (n=8). Among men, the lowest predicted probability (PP) of entering a same-sex union is for those whose only sibling is a younger sister (PP = 0.55%), followed by those with a younger brother (PP = 0.56%), those with an older sister (PP = 0.61%) and, finally, those with an older brother (PP = 0.68%). The ordering is the same among women: those with a younger sister (PP = 0.757%), followed by those with a younger brother (PP = 0.764%), those with an older sister (PP = 0.81%), and those with an older brother (PP = 0.92%). The difference between the lowest and highest predicted probabilities is 0.12 percentage points (23.5%) for men, and 0.16 percentage points (21.2%) for women.

How does this correspond to the findings of Frisch & Hviid, Blanchard & Bogaert, and and Vilsmeier et al?

I can’t really square it with Frisch & Hviid. Even though the methodologies are similar (one investigating everyone in Denmark, the other everyone in the Netherlands), the first finds approximately no result, and the second a very clear result. But Ablaza et al have both a larger sample and better statistics, and they better match previous studies on the topic, so I’ll be siding with them.

On the other hand, this beautifully synthesizes the seemingly-opposed results of Blanchard & Bogaert vs. Vilsmeier et al.

The FBOE, rightly understood, is primarily an effect of older siblings in general, not just older brothers. However, older brothers exert a slightly stronger effect than older sisters, for both men and women.

Blanchard and Bogaert were right to think something was going on with older siblings and homosexuality, and even right to highlight brothers in particular. But Vilsmeier et al were right to say they were wrong to discount older sisters, and that the “advantage” of older brothers over older sisters was so small they shouldn’t be sure it existed (although this much larger study can say more confidently that it does).

What does this mean for the maternal immune system / H-Y antigen / NLGN4Y theory of the effect6? It’s definitely awkward: the classic version of the theory doesn’t predict that older sisters should have any effect, or that siblings should have an effect at all on turning later-born females lesbian. Proponents of the theory are trying to adjust, claiming that maybe women have some kind of related antigen. Blanchard and Lippa have already proposed (though not conducted) the experimental next step: see if women with daughters have higher NLGN4Y levels than women who have never had children at all. I would also feel more comfortable if somebody replicates Bogaert’s 2006 study finding this was definitely biological and it’s not just some boring social effect like guys with more brothers having more positive male role models and so being more likely to get attracted to men.

Cremeiux Is Still Skeptical

I’d like to end on a note of “so now finally everyone agrees that birth order effects on homosexuality are real”, but Statistics Twitter personality Cremieux Recueil (Twitter, Substack) doesn’t agree. He admits that the Dutch study is the best evidence we have so far, but worries that it’s not good enough:

I don’t find these objections too convincing. Yes, gay marriage as an outcome omits most gays, but it’s still a bigger sample size than anyone else, and it seems less likely that married gays systematically differ from unmarried gays in their number of siblings for some reason (which doesn’t apply to married heterosexuals) than that they’re finding the same effect everyone else has found before them.

Conclusion

The fraternal birth order effect hypothesis has had a tough decade, but things are starting to look up. It’s been forced to abandon some of its key tenets (like an effect on male gays but not on female lesbians) and relax others (like older brothers having more of an effect than older sisters). In the process, its beautiful immunological mechanism has been cast into some doubt. But the core of the idea - that more older siblings = more gay - seems to stand. My predictions (to be evaluated whenever stronger evidence comes in):

Sibling birth order effect on homosexuality is real: 85%

Real and biological: 60%

Real, biological, and linked to NLGN4Y in particular: 40%

What about the ACX survey? I’m used to having larger sample sizes than the studies I try to replicate, but here that’s not true; Vilsmeier et al (discussed below) have 30,000 gays, whereas we only have about 1% of that number. Still here are the results: among people with zero older siblings, 4.5% were gay; for one sibling, 5.0%; two siblings, 5.3%; three siblings, 5.6%; four siblings, 9.0%. A t-test comparing gays and straights for number of siblings was marginally significant, p = 0.064. I know that’s higher than it’s supposed to be but this still increases my confidence in the hypothesis. Note that this is including both sexes of subject (ie male gays and female lesbians) and both sexes of sibling (ie older brothers and older sisters). For why I chose to analyze that way, see the rest of the post!

Overall, these data show that various factors correlated with marital instability decrease the chance of heterosexual marriage and increase the chance of gay marriage. My interpretation: from a nurturist point of view, it’s obvious why parents having a more marginal straight marriage would make kids less likely to get straight married. But there's also a plausible genetic explanation: maybe the parents have some gay genes, this is making it hard for them to stay straight married, and they pass these genes on to their kids.

I don’t understand how you could get a substantial effect size and a confidence interval including zero in a sample of 30,000 gays and 500,000 straights, but this is just one of many things about their statistics that I don’t understand.

The study tested two hypotheses: first, the FBOE we’ve been talking about. Second, the Female Fecundity Hypothesis. This was the brainchild of some evolutionary psychologists trying to figure out why evolution hadn’t eliminated homosexuality (given that it reduces procreation). They speculated that maybe (male) homosexuality came from genes for a sort of super-femininity which was bad for men but very good for women; under this model, female relatives of male homosexuals would have more children than normal. But in fact this study found the opposite: they had fewer. This makes sense if they’re getting some of the gay genes and so have less interest in heterosexual sex than normal. But it means the mystery of why evolution allows homosexuality is still unresolved.

Even granting that the FBOE is true, why does adding more younger siblings make you less gay? One possible answer (as discussed in the footnote above) is that if you’re gay, it means your parents had some of the genes for homosexuality, which means they weren’t as committed to the whole heterosexual-sex-for-procreation thing as usual, and we should expect them to have fewer kids, and therefore for you to have fewer siblings. But another theory, discussed here and here, is that the same maternal immune response which makes fetuses gay can, at slightly higher strength, kill them. If during pregnancy N the response was strong enough to turn the fetus gay, then during pregnancy N+1 it might be strong enough to kill them. Therefore, gays have fewer younger siblings, and so people with many younger siblings are less likely to be gay.

Can H-Y antigens explain the other birth order effects found on the ACX survey (and general firstborn advantage in math, physics, etc)? It’s a tempting hypothesis, since math, physics, and the ACX readership are all disproportionately male, and any process which gave people less-male-typical brains would drive people away from these things. But I found that the ACX birth order effect was social and not biological, and a Norwegian team found the same on their own data. Meanwhile, Bogaert’s study found the homosexuality effect was biological and not social. I don’t entirely trust either set of conclusions, but as long as they both stand, they weakly suggest these are different effects.