Highlights From The Comments On Vibecession

...

[Original post: Vibecession - Much More Than You Wanted To Know]

Table of Contents

1: When was the vibecession?

2: Is the vibecession just sublimating cultural complaints?

3: Discourse downstream of the Mike Green $140K poverty line post

4: What about other countries?

5: Comments on rent/housing

6: Comments on inflation

7: Comments on vibes

8: Other good comments

9: The parable of Calvin’s grandparents

10: Updates / conclusions

1: When Was The Vibecession?

…

Kyla Scanlon writes:

Hi! I’m the person who coined and first published this term. I’ve been studying this phenomenon for the past four years, so forgive the rather long comment! A quick factual clarification: the Vibecession began in 2022 as the sentiment–data divergence that opened up that summer is the real starting point. The decade before didn’t have the same shape of malaise, which you can see in the sentiment data you included. People who’ve also been working on this topic tend to focus on the same pressures you outlined like housing, education, measurement problems which are absolutely part of the story. Maybe this is what you meant by smoking gun, but the Vibecession has crossed into somewhat of a meaning-making crisis which shows up in collapsing trust and inconsistent reactions to the data. Every generation has one of these, but ours is flattened across all ages due to social media and those tighter economic constraints. Expectations around future stability collapsed at the same time institutions lost credibility, and that combination changes how people interpret even good data. Also the post-2020 political environment runs on performance and constant identity signaling, and economic sentiment gets lost in those dynamics, which is why the usual models don’t fully explain what’s going on. Finally, we really aren’t in one right now, as the economic data has deteriorated meaningfully and the negative sentiment is warranted at this point.

I appreciate this guide to the original intent of the word, but I claim ‘death of the author’ - it seems to me this is more than just a two-year problem. I remember people complaining about hellworld, the broken social contract, the Boomers tearing up the bridge behind them, vanishing opportunities for the young, the blackpill of modern life, etc, well before 2022. Memory can be faulty, but don’t we need something like this to explain the Trump campaign, the Sanders campaign, Chapo Trap House, Red Scare, 4chan, and all the other mid-2010s politicians and media telling us that things were worse than they’d ever been and outrage was the only acceptable response?

And I appreciate that the economic data have gotten worse so that some level of worry is now justified. But GDP growth last quarter was 4.3% (without AI it would still have been like 4%). And I still hear people they’ll never be able to have a family but it doesn’t matter because it would be immoral to bring children into a world where they could never have any chance of getting ahead or living a normal life. Even if we’re in a mild recession now, that doesn’t sound like mild recession talk!

Still, Kyla has spiritual copyright on vibecession, so maybe we need another phrase to discuss the longer-term hypothesis. I propose “The Great Vibepression”.

TTAR writes:

I was a doomer when I graduated in 2014 because that’s what my parents and literally every single media outlet and professor were preaching to me, then I got a job right out of a college with a mediocre (3.6) GPA from a state school and went to work as an analyst at a midsized regional bank, got promoted internally a few times and lived very frugally with my wife (met at work), now I’m able to be a stay at home dad with our kid while she works from home. We live in Oklahoma; we bought new construction last year for $200k with some spare cash I had laying around in a brokerage account. So I am pretty fully cured of the doomerism, success is trivial. My bosses and coworkers constantly praised the fact that I approached my job with gratitude and focused on identifying the goals and achieving them efficiently and optimally from 9-5 every day. That’s it. No late hours, no connections or networking or anything else fancy.

Good for TTAR, but I’m including this one here as confirmation that people graduating in 2014 felt like “my parents and literally every single media outlet and professor” were preaching doom at them.

Moose writes:

Every explanation for the vibecession that does not attempt to explain why there is a huge drop in 2021 specifically and persistently lower vibes for the following years should be disregarded. I think the best explanation is just inflation: this is what is most different in 2021-2024 compared to previous time periods, but you can also blame the shift to remote work, or higher housing prices. Examples of bad explanations would be “phones bad”, “media bad”, or “inequality bad” without explaining why they became worse in 2021.

I agree that if you follow the consumer confidence numbers and date it to 2021-2022, inflation is an easy culprit and we don’t need to look for anything more. My theory predicts that some kind of vibecession will continue even when inflation is far in the past.

Zahmakibo writes:

> “There is one anomaly, which is that I remember people complaining about the bad economy and the Boomers and hellworld since well before 2020 (consider the Trump and Sanders campaigns), but the official vibes didn’t crash until COVID. Is my memory faulty?”

my memory is the same, and I’m now asking the same question.

every chart in this post seems to support, or at least not contradict, the following story:

- 2008: Subprime mortgage crisis. economy is bad. vibes are bad

- 2009-2018: economy steadily improves. vibes steadily improve.

- by 2019, vibes are about as good as 1998.

- 2020: Pandemic. economy is bad. vibes are bad.

- 2021-present: economy is... complicated? stocks are good. wages briefly shot up, then slowly declined, and are now rising again. recent grad unemployment is rising. vibes are improving, but still bad in absolute sense.are we just conflating two different trends?

- a mysterious meta-vibecession in the 2010s

- a real but explainable vibecession in the 2020s

In 2008, a lot of people thought the Great Recession heralded the end of capitalism - either to be replaced with something better, or at least to degenerate into some obviously feudal dystopia that would end the charade and get everyone to finally agree that the system was rotten.

But actually, capitalism shrugged off the Great Recession just fine, and continued exactly as before. That must have been a bitter pill to a lot of budding socialists. I wonder if something about the situation broke people’s brains.

Erica Rall writes:

For young adults in particular, I don’t think the bad vibes are at all new. My go-to illustration is the first verse of the theme song for Friends, which started airing in 1994:

“So no one told you life was gonna be this way / Your job’s a joke, you’re broke, your love life’s D.O.A., / It’s like you’re always stuck in second gear / When it hasn’t been your day, your week / Your month, or even your year”

I’m younger than Erica, and have less pop culture literacy: can someone tell me whether the Friends theme song was meant to express a zeitgeist that would be immediately recognizable by and sympathetic to most viewers, or whether we were supposed to interpret it as referring to a few especially unlucky people?

2: Is The Vibecession Just Sublimating Cultural Complaints?

Tanya Jarvik writes:

Maybe people are complaining about not having enough money these days because the amount of money it takes to produce a feeling of abundance is larger in the absence of community, sense of purpose, “my life matters” etc.

The two most certain things in the world are that people will suspect every social complaint of being a proxy for economic problems, and that people will suspect every economic complaint of being a proxy for social problems.

The strongest argument against this position is that the vibecession started sometime between 2008 and 2023, and I don’t think this was an especially bad time for community and purpose compared to any other time since the 60s. I don’t think earlier periods of social dissolution were sublimated into economic complaints.

Alex Zavoluk comes down in favor:

“Players are great at identifying problems but terrible at coming up with solutions.” This is from Mark Rosewater, the head designer of Magic: the Gathering. His point is that when playing a game, it’s easy to tell that you aren’t having fun, but not always so easy to know exactly why or how to fix it. And in my experience, it’s very true--people will repeat platitudes they’ve heard from others about what makes a game fun or not fun, but the complaint manifestly does not apply to the situation they’re describing. Or there’s another situation which totally resolves the complaint but they’re still not having fun.

I think the same principle applies more generally. People are unhappy, and they can easily determine that. But that doesn’t mean they know what would change that fact. Money and material standard of living are easy to point to as things that would make life better, but my understanding of the research is that how much happier people think they will be after making more money is higher than how much happier they actually become. People in their 20s are now Gen Z, i.e. people who were raised after several generations of an increasing trend to shelter children and prevent them from having any independence, and who have been exposed to a constant stream of social media since middle school. One can debate whether these really are the problem, but I certainly wouldn’t expect zoomers to say, “oh yeah, obviously I’m unhappy because I was protected from challenge as a child, had to be driven everywhere, was never allowed to practice being independent until after college, community life has been severely hampered, and I’ve been exposed to brain-rotting forms of media since I was old enough to read, in total contrast to my parents and every previous generation” even if that’s true.

Alex also mentions the political angle:

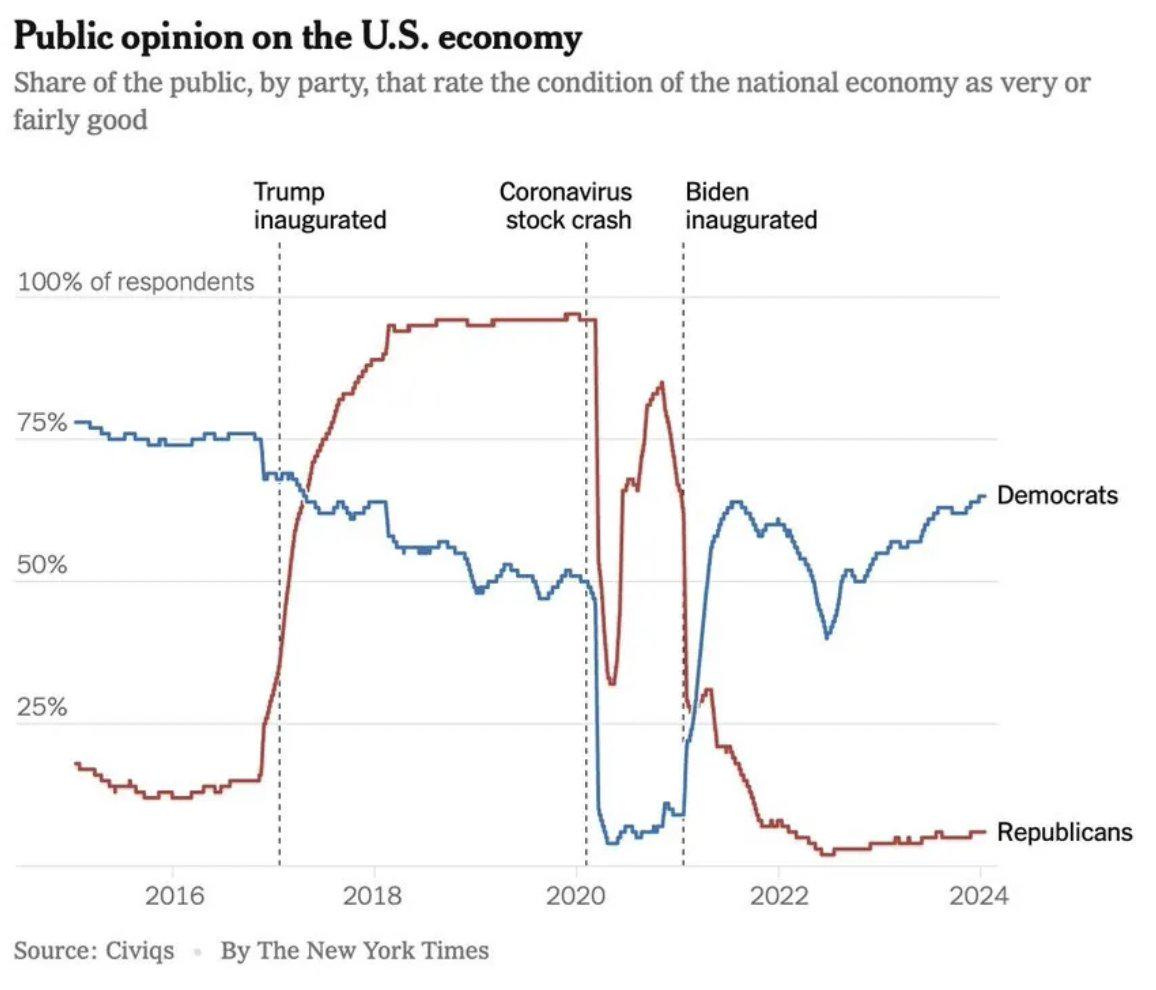

Obviously nothing real changes the exact second a new president is inaugurated, so people must be using questions about the economy to express their overall happiness about the state of the world.

Alex asks whether increasing political polarization could make this worse. Both parties’ extreme factions share a tendency to treat the country as controlled by a hegemonic conspiracy of their enemies - the woke coastal elite Soros cosmopolitan establishment, or the neoliberal fat cat Koch Brothers tech oligarch blob. Does this mean everyone is getting some multiple of the “other party’s president is in power” effect all the time?

3: Discourse Downstream Of The Mike Green $140K Poverty Line Post

…

Shovacklerod writes:

Scott have you read Mike Green’s viral post on this?

His main argument is that the poverty line is miscalculated, but in context of declining middle class sentiments—

The more interesting thesis is that there exists a “valley of death” where two parents in the workforce need a combined ~$140k salary otherwise the cumulative “participation costs” of a fast modern society (for example a phone plan or child care) make year-over-year capital accumulation near impossible.

I haven’t, but other commenters suggest reading responses, including Noah Smith’s The $140,000 Poverty Line Is Very Silly, Jeremy Horpedahl’s The Poverty Line Is Not $140,000, and Tyler Cowen’s The Myth Of The $140,000 Poverty Line.

Most of these focus on Green’s explicit errors - for example, he gets most of his cost-of-living numbers from Essex, NJ, an especially rich county, then compares them to average earnings. Correct half a dozen things like this, and the real poverty line is probably somewhere between $35K - $60K. The percent of Americans below this line continues to decline every year, as it has for decades. Green finally pseudo-apologized, lambasting the “mockery machine” of the “cognitive elite” but admitting that his post “was never intended to go viral and was written for my existing audience that tends to be pretty understanding that I don’t do this for a living, but rather as PART of my living”

Still, many people took Green’s article as a starting point to contribute to the Vibecession discourse, so let’s go over the ones that touch on our topic in more detail.

Lincicome titles his response The $140,000 Poverty Line Is Wrong, So Why Does It Feel Right?, and blames Baumol’s cost disease:

As the Financial Times’ John-Burns Murdoch just detailed, Americans’ overall cost of living has improved over time, but certain highly visible and socially desirable services have become more expensive. That’s not a conspiracy against the middle class but instead just Baumol at work:

“[A]s countries develop economically, the same productivity growth that drives down the cost of tradeable goods causes the cost of in-person services to balloon. Wages in sectors like healthcare and education that require intensive face-to-face labour, and have slow (if any) productivity growth, are forced upwards in order to attract workers who would otherwise opt for high-paying work in more productive sectors. The result is that even if people keep consuming the exact same basket of goods and services, as living standards in their country increase they will find more and more of their spending is going on essential services.”

Sectors where productivity grows slowly and prices outpace inflation—health care, education, child care, personal services, housing (construction), etc.—happen to be the same ones that middle-class families notice most and that signal social status. As we’ve all gotten richer, moreover, these services have transitioned from luxuries to expectations. Throw in the hedonic treadmill and the fact that you can’t price-shop schools or hospitals the way you can TVs, and public alarm is all but inevitable.

I’m suspicious of including “housing (construction)” on this list - couldn’t you use the same argument to reclassify any manufactured good as a service good? - but the rest of these are well-taken.

Still, did Baumol or the other economists who first discussed the effect in the 1960s predict it would make people feel like things were outright worse, as opposed to just getting better less than would be expected from raw productivity numbers? Seems strange.

Also, hasn’t the Baumol effect been basically constant since at least the Industrial Revolution? And isn’t the Vibecession only 5 - 20 years old?

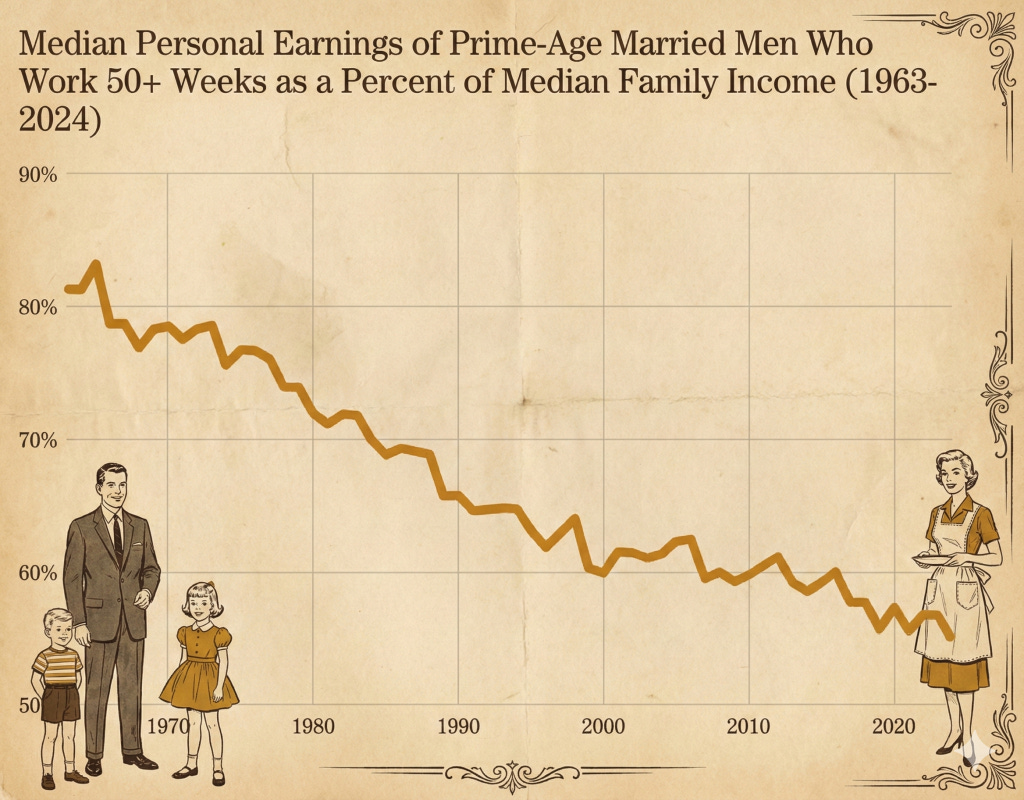

Matt Bruenig has his own response to Green, Why Do People Feel Like They’re Falling Behind? He bases his argument around this graph:

…which is just making the common-sense point that, as society shifts from one-income to two-income families, the husband’s share of family income drops from ~100% to ~50%.

So, Bruenig argues, if everyone is trying to keep up with the Joneses, and the Joneses are a dual-earner family, then this single working man has gone from making 100% of his comparison point, to making only 50%.

This is a cool potential cognitive bias, but is anyone really making this mistake? Vibecession complaints hardly seem limited to men in traditional one-earner households wondering why they’re not making as much as the neighbors whose wife is a fancy lawyer. My impression is that they include both two-earner families who still feel like they’re falling behind, and (most of all) young singles who are comparing themselves to their young single friends where this issue never comes up in the first place.

Matt Yglesias uses a similar strategy in You Can Afford A Tradlife.

He argues that the reason most wives work these days isn’t because we’re poorer (and they have to work to survive), but because we’re richer (and so wives can make so much money working outside the home that the opportunity cost is too high to pass up).

A single earner could still support a family on a 1950s lifestyle. It would just feel like a failure, because we don’t realize how much worse than 1950s lifestyle was compared to our current conditions.

The article’s paywalled, but you can get a pretty good sense of the argument from these paragraphs. After determining that the median man makes about $80,000/year, he writes:

Let’s say our $80,000-a-year man is living in the Jacksonville area. The Department of Housing and Urban Development calculates what are called Fair Market Rents for each American metro — this means the 40th percentile rent for a home with any given set of characteristics. They say F.M.R. for a three-bedroom home in the Jacksonville area is $2,163. That comes out to about 30 percent of Mr. Median’s annual income.

Can you really get a place to live for that little? Here’s a lovely three-bedroom home in the East Arlington neighborhood for $2,020 a month, and it’s zoned for an elementary school with a 10-out-of-10 ranking from GreatSchools.

It’s true that 1,617 square feet is on the small side for, say, a family of five in the contemporary United States. But the average size of a new single family home was 1,289 square feet in 1960 and 1,500 square feet in 1970. Two of your kids are going to need to share a bedroom, but that’s how people lived back in the day.

There’s more to life than housing, of course, but I started there because that’s the largest item in a household budget. Durable goods like furniture, cars, and appliances have all become better and more affordable since the mid-1960s. That’s partially offset by rising prices for things like college tuition, child care, and health care. But in the 1960s, most young people didn’t go to college. The way health insurance works, you only need one worker in your family to get a job-based health plan. And of course, with your wife serving as a full-time homemaker, you don’t need to worry about child care expenses.

The big thing is that, with a larger family, you literally have a bunch of mouths to feed. But the model here is to replicate how people actually lived in the mid-1960s, which is that they dined out much less frequently and also spent a much larger share of their total income on food.

When I try to retrace this, it seems possible, but barely. I imagined doing this in Sacramento, to be near family. Suppose I make $80K pretax = $6.6K/month pretax = $5K per month posttax. A cheap 3-bedroom house on a nice-enough block is $2200 mortgage, assume $3K after property taxes etc. A cheap new car is $350/month. Food can be arbitrarily low if you’re willing to eat rice all the time, but let’s say $250/month. CoveredCalifornia offered my family of four healthcare for $600/month. So top four expenses take $4200/month of the $5000/month pretax income. I don’t know; seems tough. I would like to see a more thorough breakdown of an average 2026 vs. 1956 man’s likely budget.

There are also some areas where it’s harder to separate genuine declines from rising expectations. Most people in the 1950s didn’t have health insurance. Was that because they accepted lower levels of health, or because medical care was cheaper, and easy enough to afford out-of-pocket? Probably some very complicated combination of both. And it might be impossible to get certain kinds of 1950s medical care today, i.e. a bed in a cheap low-quality shared hospital room.

(some of the best discussion around this came from the response to Elizabeth Warren’s The Two-Income Trap, see eg Matt Bruenig here)

Still, I find this tangential to the main point. Yes, a few conservatives complain that it’s hard to have a single-income family. But most vibecession complaints come from singles or dual-earner households!

4: What About Other Countries?

…

Dionysus writes:

Did you know that China also has a vibecession?

If even China can’t regulate social media heavily enough to prevent this phenomenon, how can any liberal society possibly hope to?

The link goes to an NYT article, which includes quotes like:

Using apps like RedNote and Douyin, people are reviving memories of the 2000s and the early 2010s with photos of daring outfits, upbeat songs and vintage TV commercials, all of which, in different ways, evoke a time in China that pulsed with optimism. “The music back then throbbed with exuberance, brimming with the sense that the future could only get brighter,” a middle-aged man said in a RedNote video. “Today’s lyrics begin with lines like, ‘We’re trying our best to survive.’”

And

The boom-time beauty meme is the latest expression of a Gen Z counterculture born of disillusionment, the recognition that they may be the first generation in half a century unlikely to surpass their parents’ standard of living, no matter how hard they try.

Over the past five years, this quiet resistance has taken many forms. It began with “lying flat,” a refusal to join the rat race. Some chose to pursue the “run philosophy,” or emigrating in search of freedom and brighter prospects. Others declared themselves the “last generation,” vowing not to have children. Still others embraced “let it rot,” giving up on difficult goals rather than battling for uncertain rewards. To show they could care less about career prospects, many took to wearing “gross outfits” at work.

This is especially crazy in China, where GDP per capita is now ten times what it was back during the “Boom Years” that everyone reminisces about. This might be the smoking gun that people’s economic beliefs are totally unmoored from how rich they are.

The Chinese story has an obvious moral: people care about growth rate more than level. But even this doesn’t work for America - our Vibecession doesn’t correspond to a period of unusually low growth.

machine_spirit writes:

It’s interesting to compare it to Europe as the control group. Unlike the US, whose economy muddled through just fine during the last decade, we are currently experiencing a massive economic decline that could soon turn into a full-blown collapse. And yet, outside of debates about immigration or foreign policy especially regarding Ukraine you don’t really hear the same level of rancour about ‘things being bad’ in the local media.

I’m surprised to hear this. I hear many economic complaints from Europeans, but I suppose this passes through my own American filter bubble which is incentivized to talk about economic hardship for its own American reasons.

Golden Feather writes:

I am an Italian currently living in the US. My main guesses would be:

Right-wing parties control a supermajority of TV and print media. They have also been in the govt most of the time, which means they control the state TV and have an interest in presenting things as rosey. The much older population makes the internet less relevant for public sentiment. Even in the few years where they were at the opposition, they mostly focused on immigration and crime to rile up popular sentiment, I guess because the population is older, their voters even moreso, so they care more about that than about the economy

The absolutely massive and unsustainable intergenerational transfers keep everyone somehow sedated. Maybe your wage is terrible, especially after taxes, maybe you’re unemployed and it’s hard to find a job, but grandma will be happy to help out her only grandchild. Most don’t realize they’re just getting their money back. This is bound to collapse soon but see the point above, the media really don’t want you to think about it.

It’s a lot easier to feel like you’re providing opportunities for your kids. The stereotypical rich-kid private uni is, even as a proportion of median income, still a lot cheaper than an Ivy and probably even an unremarkable liberal arts school. Unless you want to study business or law, there just aren’t private unis (there is one for medicine but it’s universally considered bad). Public uni is cheap and usually open access. If there is some kind of selection (eg medicine or architecture), it’s a standardized test, so you don’t have to worry about optimizing your kid’s extracurriculars, you can just have them do what they like or what is important to you. You don’t have to worry about living in a good school district because anyone can enroll in any public HS, and with very few exceptions private HSs are worse. If you are more aware about the state of the country than most of your co-nationals, and want to send your kid to study abroad, any other EU country is bound by treaty to treat them exactly like their own citizens, you just have to make sure they speak decent (not excellent, decent) English. The anxiety Americans have about setting up their kids for success is assuaged, partly because Italians are less ambitious but mostly because it’s objectively much easier to do so.

Related to the above point, but the EU ensures that in the worst countries there is a lot of evaporative cooling. The most ambitious Italians are not doomscrolling about how terrible the tech job market is in Italy, they’re learning German or looking for a job in the Netherlands. And when they’re there they complain even less than the locals because well, nobody likes an ungrateful guest, they don’t want to feel they uprooted their life for nothing, and it’s still much better than Italy - the usual reasons immigrants are much more appreciative than natives everywhere.

The last point obviously does not apply to the richest countries themselves (hence why populism in the Nordics, Germany and the Netherlands looks more like MAGA than the rest of the European right), but the first three do, mutatis mutandis. The second and the third one even moreso, opportunities are as equal as they can realistically be and the safety net really robust. Nobody is afraid they will end up destitute, and opportunities are as equalized as they can realistically be across the bottom 95% (maybe even 99%) of the kids. Once you take away those two sources of anxiety, people tend to be a lot more relaxed.

Citizen Penrose writes:

On the Brooklyn theory. If media sentiment was the main factor wouldn’t you expect it to vary in English speaking vs non-English speaking countries? Whereas, you get the same phenomena in all the developed countries as far as I know.

I don’t know which direction this pushes. I think the UK is having the same problem with London that we have with Brooklyn, and China has their Tier 1 cities. I don’t know what the situation is in France or Germany, but I’m also not sure the Vibecession is happening in those places.

JBB23 writes:

To the extent you believe the large consumer confidence surveys (Conference Board and UMich) accurately measure sentiment, there are dozens of subindices which shed light on the actual reasons people feel bad.

A few things to note - there’s no obvious differentiation by either age or income, so any hypothesis relying on things being especially bad for young/poor/middle class is not showing up in this data. The subindices on labor markets, income, and the stock market are strong (as they should be). The subindices that are weak are related to inflation, buying conditions for durables (inflation again), buying conditions for homes, and vibier questions like expectations for retirement, expectations for future income, etc.

The OECD also produces consumer confidence surveys and the US is pretty middle of the pack compared to other advanced countries for the last three years - US, Australia, western europe, UK, japan, are all in the -1 to -1.5 z score range historically. China is the worst, around -2 z scores. Interestingly, Mexico is one of the few places with high consumer confidence right now.

So for me, the synthesis should be any explanation is pretty global and pretty widespread across demographic groups. That suggests inflation and media negativity.

5: Comments On Rent And Housing

…

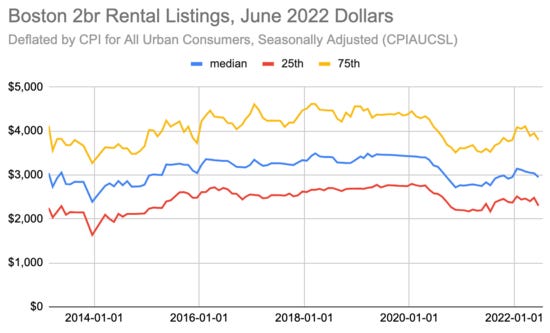

Fred writes:

I don’t actually buy that city rents haven’t gone crazy. We were renting in the inner-inner not-quite-suburbs of Boston for $1700 in 2021. When we checked back in 2024, it was at $2800. Pretty sure that’s roughly in line with overall Boston rental price movement. Is NYC maybe not the best to look at because of all that rent control I always hear about? (This sounds so simplistic that it has to be wrong, and I know nothing about NYC, but I have to throw it out there).

Good point. The chart I gave to show relatively-stable rents in NYC was 2010 - 2023. Jeff Kaufman has 2013 - 2023 for Boston. Here is the inflation-adjustion version:

Basically no change during that time, weird. But Demost writes:

It may not just be rent-controlled apartments.

If you look into the rents in Germany and Switzerland (the ones I know about), there are two very different measures of rents, even after adjusting for flat sizes etc:

1) The median rent of a person who lives in the city.

2) The median rent of a person who moves to the city.

I believe that the second one has absolutely skyrocketed in the last 20 years in all major German and Swiss cities, while the first one has only moderately increased. The reason is that rents are sticky. People who have lived in the same flat for 20 years have seen limited increase of their rents, whereas rates for new tenants have increased dramatically.

If you look into official statistics, as Scott did, they will probably measure 1), and see a moderate increase. But for young people, 2) is much more relevant.

I don’t know whether it is the same for large US cities. The housing markets are different, for example in Germany (and Switzerland?) there are much fewer home owners than in the US. But on this side of the Atlantic, I think this is a very major factor for why many young people are struggling with their rents.

I’d like to know more about what factors hold rents down for long-time residents. Without rent control laws, wouldn’t landlords raise rents on existing renters each year to keep them equal to the market price?

David Levey writes:

Has Kevin Erdmann decisively figured out why we seem to be in a perpetual “vibecession,” where people feel much worse off economically than the usual numbers — real wages, household incomes and consumption, etc. — would justify? A situation with major political implications, in that every administration successively finds itself disappointing its supporters who believed promises of falling costs of living and rising prosperity.

He argues, in a new paper for the Mercatus Center, “We Are Not as Wealthy as We Thought We Were,” that a large portion of the wealth of U.S. households, which is found in the value of their homes, is, in fact, not real wealth, but a result of being trapped in rising cost accommodations in a housing-poor society. Here is the abstract:

This is interesting, but I don’t think it affects most of our measures of vibecession, which aren’t looking at real estate wealth. The income of people today should be comparable to the income of people X years ago before the housing increase happened, with the exception of how much they spend on housing/rent, which we’ve already priced in.

Aristides writes:

I will be honest and my vibes are low entirely because of the mortgage increase. I had everything ready to buy a house in 2021, and the housing prices rose so much I can’t afford one. I’ve been living in rentals for 4 more years than I expected. Sure, my rent only increased by 10%, but now I have a 3 year old who wants to play outside in a yard that I own, and instead we are in a tiny apartment with no yard. I’ll probably figure out how to buy a house by 2027, but 6 extra years of rentals makes this a bad decade for me even if my income increased by 50% over this time.

Question for Aristides and others: why is renting so associated with apartments (eg your child can’t have a yard), and buying so associated with houses? I’m not denying this is true, I just can’t fully trace the economic logic that causes it.

Ransom Cozzillio writes:

It’s obviously still possible, as you note, that housing cost increases, which are a very real issue, are carrying a disproportionate burden of “the vibes”. However, I think it’s worth noting that ~70% of Americans are homeowners. So those rising prices actually make the majority of people wealthier. Also, the homeownership rate for Millennials isn’t tracking much behind that for the Boomer at the same ages (a couple percentage points). Yes, the younger generation is paying more, inflation adjusted, for those houses. That’s not ideal. But also it can’t really be said they are getting negative vibes from being locked out of homeownership or something.

6: Comments On Inflation

…

Citizen Penrose writes:

“I think inflation calculations are pretty good.”

I wouldn’t be so quick to dismiss the argument that inflation figures are wrong. Like you said, if inflation has historically actually been much higher it provides a very parsimonious explanation for all the other data.

CPI might do a good job measuring short term changes in inflation, say year to year, but it’s very unclear that it can be used to make long term comparisons between different decades, as all figures in this post implicitly do.

I liked this post a lot about ways CPI figures can be systemically wrong stretched over time:

https://devinhelton.com/economics/gdp-and-cpi-are-broken

The metric which that post suggests as a more realistic measure of real incomes is how many hours of median wages are required for a 30 year old man to provide: A running car. A house. 2k calories of food daily.

I asked chat gpt’s deep research to calculate an index for that basket of goods and the index has been on a secular decline since around 1970, and in 2025 was only about half the 1970 value (i.e. it takes twice as many working hours to provide those goods now.) https://chatgpt.com/share/6931e385-c8b8-800f-922f-cf2202485000

Also even if the CPI figures are right, the composition might still matter. Broadly, essential goods are more expensive now than in 1970 and consumer goods are much cheaper. Even if that looks like a wash in CPI figure it could still mean a loss in wellbeing for several reasons:

1.) Maybe consumer goods are more likely to be affected by hedonic adaptation or have negative externalities. By normal CPI measures a smartphone might be worth a million dollars in 1970, but what is the actual hedonic effect of smartphones? (maybe negative?) Having a “one million dollar” smartphone isn’t going to make up for not having a £300k house.

2.) Maybe consumer goods have steeper diminishing marginal utility. The same way having three right shoes isn’t better than one right and one left shoe, being able to afford twenty 50” tvs isn’t as good as being able to afford one tv + a house to put it in.

I appreciate your work, but when I try to check ChatGPT’s work, I find that its “basket of goods” assumes the median person buys one house per year. This means the basket massively overweights the price of housing compared to everything else, and - since the price of housing has increased the most - it massively overestimates inflation.

WoolyAI writes:

For the first time, this is less than I wanted to know, very specifically regarding inflation measurements and how we adjust for it in wages.

Specifically, I can remember around 2013 when there was a proposal that Social Security COLA adjustments (annual cost of living increases) be tied to Chained CPI, rather than CPI. And the AARP seemed very, very convinced that minor changes to how inflation was calculated would dramatically impact real people’s Social Security checks (1). I’ve seen calculations that chained CPI is 0.25-0.3% (5) lower than CPI. Which is small overall but large relative to overall inflation, roughly 2%, and compounding.

I don’t want to argue here that the goldbugs are right and the purchasing power of the US dollar has dropped by 80%. But it does seem plausible that different inflation measures, even if both equally valid, could dramatically alter the real median wage over this period.

For example, from FRED’s “Real Median Household Income” series (2), from 2000-2024, income grew from $71,790 to $83,730. That’s about a 16.6% increase over 24 years. That’s roughly a 0.6% annual growth rate. If the difference between Chained CPI and CPI is roughly 0.3%/year and real median income growth is ~0.6%/year, then how we measure inflation has a pretty significant impact on how we calculate real income, as well as every inflation adjusted measure we looked at.

And I’m pretty confident that chained CPI is valid, because in the “Real Median Household Income” data from FRED, under notes, it says “Income in 2024 C-CPI-U (2000-2024) and R-CPI-U-RS (pre-2000) adjusted dollars.” Which looks like the pre-2000 numbers are calculated using traditional CPI and the post-2000 numbers are calculated using chained CPI. This is buttressed by the fact that FRED’s chained CPI data only goes back to 2000 (3)

So, briefly, I don’t like the “Miscalculation Of Inflation” section and I wish it dove into more detail because:

#1 There are multiple valid inflation metrics. I have nothing against CPI, it’s a solid metric and we have the data going back to the 60’s, and I have nothing against chained CPI, which is the current standard FRED uses and also makes more sense (4). However, there are more inflation metrics beyond Chained CPI; Penn State lists 5 here alone (6)

#2 The impact of different inflation metrics is large enough to significantly alter the increase in real median wages, say up or down 50%.

#3 I don’t understand how the decision to use different inflation measures affects all our other inflation adjusted metrics. To make this specific, I don’t know what the real median household income would be for 2019 if we calculated it with CPI (the way we did in 1999) vs with chained CPI.

#4 The response from economists here feels…dismissive. Which would be fine if there really was a single consistent inflation metric everyone was confident in, and maybe there is, but there seems to be a lot more complexity and value judgment to inflation metrics than “just CPI”. Especially when there’s such a gap between consumer sentiment/vibes and official statistics which would be significantly impacted by different inflation measures.

#5 Which is worse, because…I cannot help but note that the kind of guys who post things like the “US Wages in Gold” or “The Fiat Crisis” (7) are disproportionately multimillionaire crypto bros who…On the one hand they all sounds like salesmen at best and scammers at worst and constantly predict a US fiscal and monetary collapse but…they did go act on those beliefs and built the entire crypto ecosystem worth at least half a trillion. Anyone who’s financial/economic philosophy directly leads to them inventing their own ridiculously lucrative alternative financial system deserves to be taken at least somewhat seriously.

To clarify, I don’t think the impacts of different inflation measures are large enough for a decline narrative but they could be for a stagnation narrative.

Real Income growth of 16% from 2000-2024 sounds like slow, solid but uninteresting growth. 6-7% total growth over that same period “feels” like stagnation.

Inflation-adjusted rents going up 40% vs 30%.

An average mortgage payment of $3.3k vs $3k compared to an average mortgage payment of $2k in 2000.

I would appreciate any insight anyone else has, as this is a subject I know worse than nothing about, I know a little. And I wish I knew more.

(1) https://states.aarp.org/what-is-the-chained-cpi

(2) https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEHOINUSA672N

(3) https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SUUR0000SA0

(4) As far as I can tell, chained CPI just attempts to adjust the basket of goods by how consumers vary their purchases as prices change. Pretend I buy 4 pounds of beef a week. The price of beef doubles. I stop buying beef and start buying chicken. CPI measures as if I still buy 4 pounds of beef. Chained CPI tries to capture my change to chicken, which is hard.

(5) https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44088

Okay, this one I’ll leave to the economists.

7: Comments On Vibes

…

Fluorescent Kneepads brings up an article asking each generation their definition of financial success, key point this graph:

By Zoomers’ metric, about 1.5% of Americans are “financially successful”. Could their high standard for success be related to why they feel like they are unsuccessful, and from there why they think the economy’s bad?

But an alternate interpretation of this chart is that every generation believes success is ~$500,000/year, inflation-adjusted to the value of the dollar when they were in their early 20s and forming beliefs about success. This is a bit of a stretch - surely Boomers have had plenty of time to update on the value of a dollar since their 20s, especially since many of them are still working and collecting salaries. But the math works out.

Victor Thorne, responding to a demand that Zoomers to justify themselves, wrote:

I’m on the older side of Gen Z (22) and it’s not really about that. I do think I’d need to make a ton of money to be comfortable, not because I actually need to spend anywhere near that much money, but because that’s how much cushion I would need to have to feel like I wasn’t on the edge of a crisis. I mean, to shop at a nice grocery store without worrying too much about prices you should probably be making at least 200k; that’s a big part of my definition of financial success (in part because better food is one of the main ‘rich people things’ I am actually interested in).

Cue commenters yelling at him for feeling like he “needs” to shop at a nice grocery store, and him very reasonably responding that the question asked about “feeling financially successful”, not about what he “needs”. So one interpretation of this question is that companies have done a better job making Zoomers feel like expensive products are part of the good life (e.g. shopping at Walmart vs. Whole Foods). I endorse this: I’m in the same social class as my parents, but I remember them shopping at the same grocery store as the poor people in their hometown, whereas I mostly shop at upscale hippiesh places.

Theodidactus writes:

I’m surprised you didn’t address one thing...but I guess it’s just a different way of saying “vibes”, still I think this connects to a lot of econ discourse and...frankly...I don’t have a good solution and it honestly scares me a little:

So, when prices go up really fast, that’s “the economy.” It’s a force external to me, and I’m mad that it’s happening, cuz I sure as hell didn’t do it.

When *my salary* goes up really fast, that’s...just me, obviously, I deserve that. I’m happy it’s happening, and I SURE AS HELL caused it.

In short: it’s an outrage if eggs cost $10, and that’s true even if I make $500,000 a year and made $250,000 the year before. That massive jump in my income was the result of my blood, sweat, and toil. I didn’t do the egg thing.

My own read on the vibes of a lot of people my age (esp. who voted for trump) is that they actually expect *the real sticker price of commodities* to go down as the result of...some unspecified economic corrective policy...and if not, well, things will be bad for whoever is in charge, and this will be true no matter how much anyone makes.

Obviously, if you know economics, you know the cost of things going down would be bad, and that your own salary going up is due as much to economic forces as anything, but you can’t fix sentiment errors like this by sitting the whole country down and having an economics lesson (indeed, I’d argue biden tried that).

Ivan Fyodorovich writes:

A key part of the “Brooklyn Theory” is that the media industry really is a total nightmare of endless layoffs, unpaid internships, city newspapers shutting down etc as Google et al. eat all the advertising revenue. They have been in an awful recession for decades and since they have the megaphones, they can spread their misery to everyone else.

I was going to ask if the media is really this powerful, but DocTam writes:

After seeing how much media opinions on big tech changed overnight in 2016 I learned how much the opinions of journalists in NYC really changes the zeitgeist of discussion. The journalism industry is so miserable with people still looking to get college degrees in a field that pays terribly. Even the alternative media economy is primarily driven by wretched journalism majors.

This was a formative experience for many people in Silicon Valley: there was a sudden turn from the early 2000s world where everyone loved technology and thought that the information superhighway was the utopian world of the cyber-future, to the late 2000s world where everyone hated techno-fascist tech-bro techno-oligarchs using The Algorithm to addict our children. Although there was some shift in the underlying terrain, the sheer speed of the change in opinion made a lot of people point to journalists realizing that tech was bad for their business and making an united decision to cover it negatively. Could the same thing happen to an entire economy? Should we subsidize journalists, on the theory that if they’re in a good mood, everyone else will be in a good mood too? Is this Chris Best’s secret plan for Substack?

8: Other Good Comments

…

Golden Feather writes:

I think a very important piece of evidence you missed is all the surveys where people answer that their own situation is fine, but the economy is bad. See eg this one https://www.axios.com/2023/08/18/americans-economy-bad-personal-finances-good

Even if we assume people rate their own situation independently of the media (very strong claim), the media must be responsible at the very least for the dissonance between their own experience and their assessment of the economy, no?

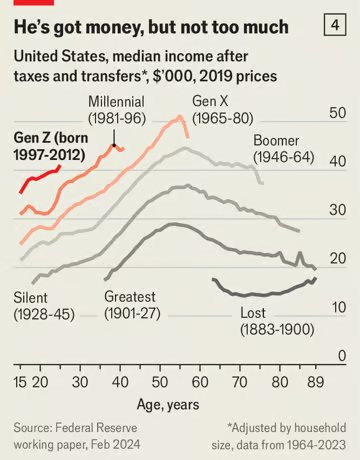

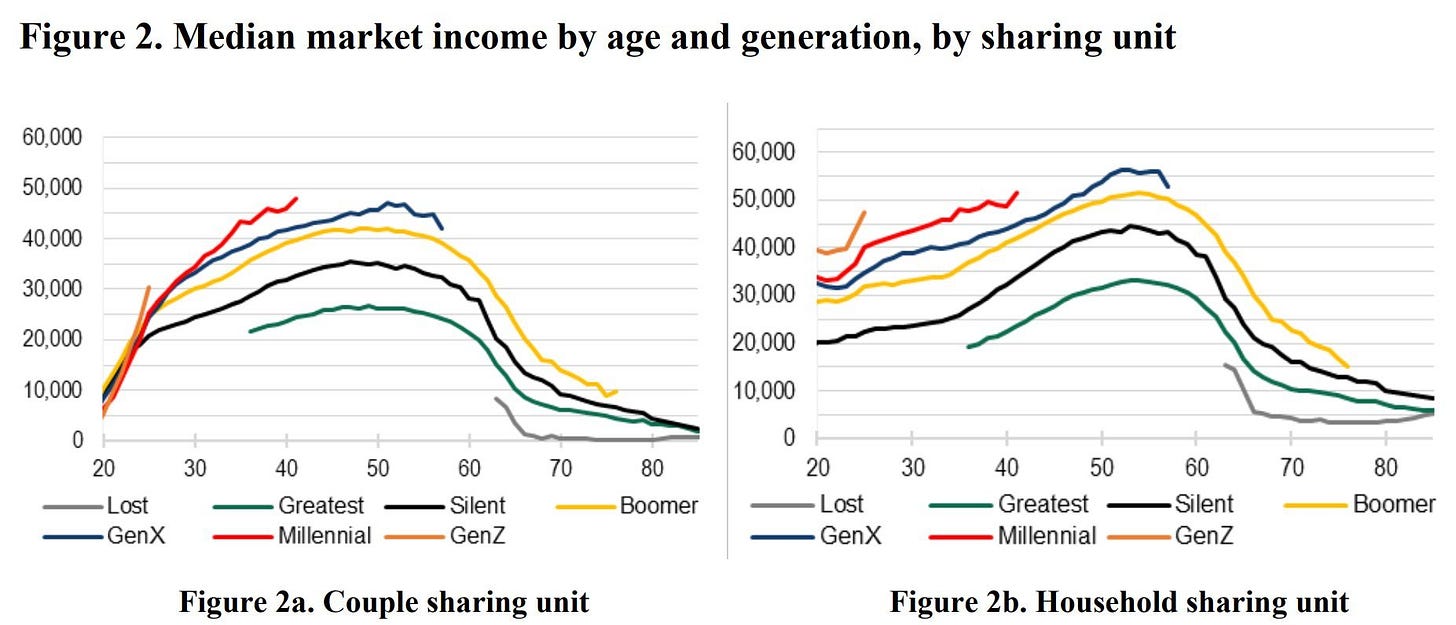

Cremieux (on X) objects to the chart showing each generation doing better than the last.

He writes that they “divided by the square root of household size”, but that “this is problematic because it means Gen Z incomes are being inflated to the extent they live with their parents.” I’m not entirely sure what he means by this - if Zoomers were being counted as living in a large household, wouldn’t that deflate their income (by dividing by an artificially high denominator)? Maybe he means Boomers are getting deflated because their adult kids are counted as part of their household? But this wouldn’t affect the 20-year-old band where we’re doing most of the comparison.

In any case, he includes a “couple sharing unit” graph that avoids this problem:

…and it still shows every generation doing better than the last, albeit by a smaller amount.

Joel Long writes:

I have not been able to find data to assess this, but my pet theory is that the basket of consumption middle class people are chasing as “normal” has changed.

Anecdotally, I see this on:

1) expected square footage per person in housing (e.g. kids sharing bedrooms seems much less universal than it used to be)

2) vehicle space per household member. Meaning both size and number of vehicles. My perception is also that “cars as status goods” has made its way further down the socioeconomic ladder than it used to be but that’s wild speculation.

3) frequency, duration, and distance of vacations: I blame this one, perhaps unfairly, on the prevalence of travel vloggers. Here there is some data: https://ourworldindata.org/tourism

Basically: while people have gotten wealthier over time, the standard of living they’re pursuing has increased even more, which can come out as feeling poorer on net.

Mika writes:

I think the low friction of applications is a big driver of this (both in jobs, college, dating etc). I am in my final year of an Electrical Engineering degree and applied to ~500 full time jobs this fall. I am a reasonably economically minded person, I try to avoid pessimism know the stats on how everything has gotten better over time, pro capitalism etc. But even I was having trouble mentally reconciling what I knew about the numbers with my feeling from the inside of like being rejected over and over again while being in a pretty in demand field. Additionally my algorithms started to pick up on this and fed me content about how the sky was falling no one was getting hired etc. Things got pretty dark for me mentally for about a month. I’m mostly on the other side of it now, I got some offers (ones I probably won’t take and because they are in the wrong EE field) , and a lot of interviews scheduled etc. But I just don’t think humans are built to mentally understand “ You will have to be rejected multiple hundreds of times over a month or two to get a job”. Even if it’s relatively guaranteed if you put in that effort.

I hadn’t considered the bad experience → complain online → algorithm shows you pessimistic content trapped prior loop.

9: The Parable Of Calvin’s Grandparents

…

Calvin Blick writes:

Imagine having to get up at 4 am every morning, drive an hour to work, and then run a meat shop singlehandedly--dealing with customers, slicing cuts of meat, dealing with all the behind the scenes stuff like rent and suppliers. You get home at 7 or 8 pm every night. You only rarely get to see your kids. You have a small house in a not-great neighborhood.

Your wife has to deal with five kids singlehandedly. Money is tight. Meat is a luxury. Your husband beats you on occasion, and no one cares.

That was the reality for my grandparents. Yes, my grandfather owned the business, but it was a really hard life by modern standards. Obviously living standards were rising rapidly which is not the case today, but none of the people complaining about how hard things are now would trade places to take on that life.

I like this comment for putting the “your life really is different from and better than past generations’ in ways that are invisible to you” argument in stark relief. But…

Liface answers:

You have kids, in fact, FIVE of them, the wonderful bundles of joy! You own your own business. You get to work in-person, providing value to real people. Your neighbors talk to each other. Neighborhood kids play in the street. Civic society is strong: you are members of a church, the Elks club, you volunteer at local events, etc. You live near extended family. With no internet, you only compare your situation to your immediate neighbors. The economy appears to be growing and prospects for the future look good.

…I also like this one for how it turns Calvin’s comment on its head and makes me more sympathetic to the cultural proxy argument. But…

Calvin answers:

You are definitely taking an extreme "paint a rosy picture" view here. My grandfather rarely saw his kids. He never made it to a single baseball game or activity. I have worked enough customer service jobs to know how utterly draining they are, and I've known enough people who owned their own business to know how brutal that can be. My grandfather was a member of a church (which played a big part in his life; kids went to Catholic school, etc), but he definitely didn't have the time or money for the Elks club or volunteering.

…I really like this one because it helps show how dubious and contingent the cultural proxy argument is.

Aella talks a lot about how she used to have a manufacturing job, hated hated hated it, and decided to switch to sex work so she never had to do anything like that ever again; this seems like a pretty common opinion among people who have legit worked in factories (cf. how many of them are motivated by the dream of giving their child a better life where they won’t have to work a factory job). And we’ve already talked about how the average parent now spends far more time with their children these days than they used to.

If it were as easy to quantify the intangibles as it is to quantify GDP, would we find that we’re in a cultural vibecession, where the intangible parts of life are also getting better and we’re just ignoring it out of the same pessimistic bias which is confusing our view of the economy?

J Nicholas adds:

The thing is, there is nothing stopping most people from living a lifestyle just like Calvin’s grandfather. You can totally get a job running a small business in a very rural area with all those things you describe.

There is a butcher in a village near me who asks me, every time I see him, whether I have any interest in taking over his business when he retires. He hasn’t shown me his books (although I’m sure he would if I asked), but he clearly makes well over $100,000/year. I have no relevant experience, so I’m sure if he asks me he is asking lots of other people. Nobody has taken him up on it (except the Amish, but he doesn’t like them and doesn’t want to sell to them).

Would young people today be happier if they chose that lifestyle? Very possible. But they don’t want to, even if they can.

If you disagree and think this sounds like a great offer, you can message J Nicholas here and see if he’ll put you in touch with the butcher! Be sure to email me too, so I can check up later on how it went.

And J has written more about what he calls “the myth of the cost of living crisis” on his own blog.

10: Updates / Conclusions

My strongest update is on the stories about vibecession-like sentiments in China, where incomes clearly, obviously, grew by a factor of 5-10x in the past generation. This demonstrates that vibes can be totally divorced from the real economic situation, and makes me less neurotic about searching for some way that the US vibes could be correct.

My second strongest update comes from Alex’s chart showing wild swings in partisan ratings of economic health when a president from a different party gets elected, which again show vibes totally divorced from reality.

The strongest counterargument is that the housing (not rent) situation has genuinely been awful since about 2020. If you want to argue that the bad vibes began then, and are entirely about not-yet-homeowners despairing at their chances of ever owning a home, then those bad vibes would be fully justified.

I’m also more open to taking the consumer confidence charts seriously, limiting the vibecession proper to ~2022 - 2024, and saying it was mostly about inflation, plus a side of high housing prices. All of the pessimism before 2022 was something else, mostly coming from a few disenfranchised or chronically pessimistic groups and not having as much to do with the economy in particular.

I would like to see someone seriously investigate an average 1955 couple’s budget vs. an average modern couple’s budget, discuss how far each one would go, and do a more careful analysis of who was getting the better deal, and by how much.