I.

Adam Mastroianni has a great review of Memories Of My Life, the autobiography of Francis Galton. Mastroianni centers his piece around the question: how could a brilliant scientist like Galton be so devoted to an evil idea like eugenics?

This sparked the usual eugenics discussion. In case you haven’t heard it before:

Beroe: Eugenics inspired the Nazis (and 1920s Americans) to do very evil things. But Islam inspired Osama bin Laden to do very evil things, and we rightly believe that it’s fine to practice Islam as long as you don’t use it as an excuse to do evil things. Islam isn’t bad, flying planes into buildings is bad. Likewise, eugenics isn’t bad, involuntarily sterilizing people, or sending them to gas chambers, is bad. What’s the argument against forms of eugenics that don’t do this?

Adraste: Like what?

Beroe: Let’s say - financial incentives for the most talented people to have lots of children. Something like the old Nobel Sperm Bank, where people with great socially-valuable gifts are encouraged to deposit gametes, and couples who can’t conceive naturally - maybe infertile people, maybe lesbians - are encouraged to make use of them. And making voluntary contraception free and easily available, since by far the most common reason for the less-genetically-blessed part of the population having children is that they want contraceptives but can’t access them.

Adraste: Oh, interesting. I thought you were going to say a much worse thing, along the lines of "identify people you consider genetically inferior, then offer them money to undergo voluntary sterilization”. But of course there are many things we don’t allow people to offer other people money for. Like sex work. Or organ donation. Although people are allowed to have sex and donate organs for free, we think the desperation of poverty is so compelling, and the danger of these irreversible actions so great, that we ban seemingly-voluntary economic transactions around them. Call me a BETA-MEALR, but I think sterilization should be in the same category. Still, your suggestion avoided that, so good job.

Beroe: I take it you will shortly find some other objection, though.

Adraste: A brief aside: eugenics, as implemented in the early part of the 20th century, was extraordinarily evil. We might loosely consider the entire Holocaust eugenics, based on Nazi theory of racial purity1, but even if we restrict the label to the Nazis’ specific campaign against the disabled and mentally ill, it caused about 300,000 deaths. And although “Nazis are bad” is already priced in to our moral system, here in the United States we sterilized between 60,000 and 150,000 people. Also - it wouldn’t have been any better if it was scientifically competent, but it really wasn’t2. They sterilized 2,000 people for a form of blindness that wasn’t even genetic.

Beroe: Blindness, wow. I’d only heard about the cases around mental disabilities.

Adraste: Ah yes, mental disabilities. Carrie Buck was the plaintiff in Buck v. Bell, the case where the Supreme Court ruled 8-1 that involuntary sterilization was fully constitutional. She was sterilized for a mental disability. . . after making the honor roll at her school! Probably a family member raped her, and the family was trying to save their reputation and prevent any further inconvenient pregnancies. Then they sterilized her sister, on the grounds that she was related to Carrie and so probably had the same genes. Nobody knows how many of the hundred-thousand-odd forced sterilizations in the US were like this. Probably a lot. Again, not that it would have been any better if they were all real disability cases - just that the sheer incompetence and callousness of the people charged with making these life-ruining decisions is impossible to overestimate.

Beroe: But Galton was -

Adraste: - against this kind of thing. Which brings me back to my objection to your seemingly-compassionate-and-sensible eugenics proposal. Francis Galton said we should do eugenics in a voluntary and scientifically reasonable way3. People listened to him, nodded along, and then went and did eugenics in a coercive and horrifying way. Now here you are, saying we should do eugenics in a voluntary and scientifically reasonable way. You can see why I might be concerned. People roll their eyes at slippery slopes, but some slopes are genuinely slippery, and the slope from “thinks about eugenics at all” to “involuntary sterilization campaign” seems steep enough that I would just rather people not think about eugenics at all.

Beroe: If I understand you right, you’re saying that some things are so bad that we must ban not only the bad thing, but also innocent things that bad people could use to promote the bad thing. This seems to grant you, as arbiter of which things are too close for comfort to other things, an extraordinary amount of power. As I said before, Islam has been used by bad people to promote bad things. Some people would be very happy if we banned Islam. Should we?

Adraste: You seek hard-and-fast rules, but these will always elude you. You can’t escape adding up the costs and benefits and having a specific object-level opinion. Banning Islam has few benefits and many costs. It violates religious freedom. It perpetuates racist stereotypes. You couldn’t do it if you tried, plus a billion people would declare jihad on you. And the overwhelming majority of Muslims don’t commit terrorist acts anyway. Banning eugenics is very easy. We already did it; the victory requires minimal effort to maintain. Rolling it back has many costs and few benefits. I say keep it banned.

Beroe: You can’t assess idea how many benefits it does or doesn’t have, because your principle commits you to putting your fingers in your ears and saying “la la la I can’t hear you” whenever someone discusses the issue. Consider Garrett Jones’ hypothesis that most international differences - eg between developed and underdeveloped countries - are due to IQ. And consider that IQ is mostly genetic and could be improved with eugenics. Bringing all underdeveloped countries up to First World living standards would be the most valuable thing humanity has ever done. Or consider Greg Cochran’s hypothesis that Ashkenazi Jews have a 15-point genetic IQ advantage - there aren’t a lot of Jews starving or in prison. If you could lift everyone up fifteen points, you could come close to ending poverty even within developed countries. Obviously these hypotheses are controversial, but they’re controversial not because there’s a lot of evidence against them but because everything about genetics and society is controversial because of your policy of cutting off all lines of speculation that might lead to eugenics. I maintain that if we discussed these ideas openly, we might find that they held the key to ending global poverty, crime, and disease. Meanwhile, what has Islam given us? Pretty buildings, calligraphy, and hummus.

Adraste: See, this is what worries me. I’m not sure you raise global IQ fifteen points merely by distributing condoms and subsidizing sperm banks. And if the advantages are so great - a fact which, of course, you haven’t remotely proven, merely gestured at a few renegade scientists speculating along similar lines - then it will seem so very tempting to do a bit more, the kinds of things that really could raise global IQ 15 points in a reasonable amount of time. Either eugenics isn’t tempting - in which case why do it? - or it’s very tempting - in which case we definitely shouldn’t do it.4

Beroe: The great sin of rationality is to look for justifications for your prejudices. I worry you have found a fully general one. Everything good could in theory be bad if it was implemented dictatorially and violently. You will use this as a rationalization to condemn any unpopular idea, but give every popular idea a pass based on hokey cost-benefit analyses and witty sayings.

Adraste: I may be more consistent than you think. Eugenics caused hundreds of thousands of involuntary sterilizations, ending just a few decades ago. And the perpetrators weren’t al-Qaeda terrorists or blood-crazed generalissimos who we can safely distance ourselves from. They were smug Western elites overly impressed with their own intelligence and moral crusading spirit, just like us. Show me another idea like that and I bet I’d be against that one too.

II.

I regret to say Adraste would lose her bet.

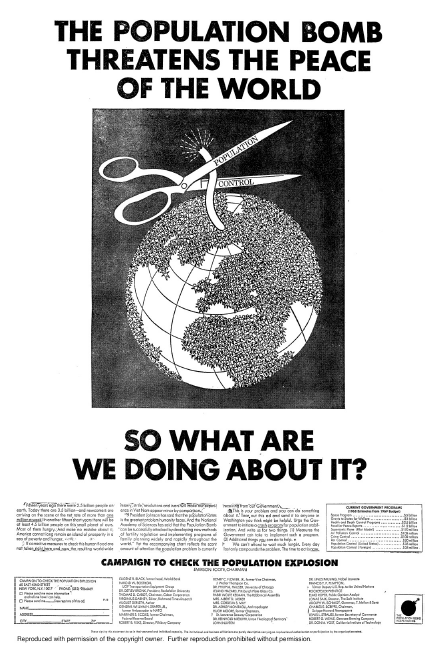

Paul Ehrlich is an environmentalist leader best known for his 1968 book The Population Bomb. He helped develop ideas like sustainability, biodiversity, and ecological footprints. But he’s best known for prophecies of doom which have not come true - for example, that collapsing ecosystems would cause hundreds of millions of deaths in the 1970s, or make England “cease to exist” by the year 2000.

Population Bomb calls for a multi-pronged solution to a coming overpopulation crisis. One prong was coercive mass sterilization. Ehrlich particularly recommended this for India, a country at the forefront of rising populations.

When we suggested sterilizing all Indian males with three or more children, [Chandrasekhar, an Indian official who shared Ehrlich’s views] should have encouraged the Indian government to go ahead with the plan. We should have volunteered logistic support in the form of helicopters, vehicles, and surgical instruments. We should have sent doctors to aid in the program by setting up centers for training para-medical personnel to do vasectomies. Coercion? Perhaps, but coercion in a good cause.

I am sometimes astounded at the attitudes of Americans who are horrified at the prospect of our government insisting on population control as the price of food aid. All too often the very same people are fully in support of applying military force against those who disagree with our form of government or our rapacious foreign policy. We must be just as relentless in pushing ·for population control around the world, together with rearrangement of trade relations to benefit UDCs, and massive economic aid.

I wish I could offer you some sugarcoated solutions, but I'm afraid the time for them is long gone. A cancer is an uncontrolled multiplication of cells; the population explosion is an uncontrolled multiplication of people. Treating only the symptoms of cancer may make the victim more comfortable at first, but eventually he dies - often horribly. A similar fate awaits a world with a population explosion if only the symptoms are treated. We must shift our efforts from treatment of the symptoms to the cutting out of the cancer. The operation will demand many apparently brutal and heartless decisions. The pain may be intense. But the disease is so far advanced that only with radical surgery does the patient have a chance of survival.

Ehrlich’s supporters included President Lyndon Johnson, who told the Prime Minister of India that US foreign aid was conditional on India sterilizing lots of people. The broader Democratic Party and environmentalist movement were completely on board.

In 1975, India had a worse-than-usual economic crisis and declared martial law. They asked the World Bank for help. The World Bank, led by Robert McNamara, made support conditional on an increase in sterilizations. India complied:

Before the Emergency, compulsory sterilization was considered in different states, but no concrete decision was ever made. At the time, only states had the authority to make a decision in the area of family planning. Once the Emergency was imposed, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, on her son’s insistence, amended the Constitution. The Constitution Act of 1976 gave the central government the right to execute family planning programs. Soon after, the central government mobilized the state political leadership and took decisive actions, such as setting up camps and sterilization targets.

Mr. [Sanjay] Gandhi allocated quotas to the chief ministers of every state that they were supposed to meet by any means possible. The chief ministers, too, in an attempt to impress the younger Gandhi, strived hard to meet those targets. Mr. Gandhi often visited villages and towns in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to encourage and approve the tremendous work being done in terms of meeting sterilization goals. Commissioners were awarded gold medals for their hard work. As a result, nothing mattered when it came to meeting the targets. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were at the top when it came to exceeding the targeted number of sterilizations, resulting in more commissioners from these states receiving medals.

Force was not only physical in form but also indirect. The government issued circulars stating that promotion and payments to employees were in abeyance until they were sterilized or completed their assigned quota of people they convinced to undergo sterilization. People had to produce a certificate of sterilization to get their salaries or even renew their driving/ rickshaw/scooter/sales tax license. Students whose parents had not undergone a sterilization were detained. Free medical treatment in hospitals was also suspended until a sterilization certificate was shown. Those who suffered the most were people associated with lower classes. These unfortunate people were picked up from railway stations or bus stops by policemen, regardless of their age or marital status. Poor, illiterate people, jail inmates, pavement dwellers, bachelors, young married men, and hospital patients were all victims.

In the end about eight million people were sterilized over the course of two years. No one will ever know how many were “voluntary” by standards that we would be comfortable with, but plausibly well below half.

The West didn’t just tolerate this process, they supported it and cheered it on. The Ford and Rockefeller Foundations provided much of the funding. Western media ranged from supportive to concerned-for-the-wrong-reasons; my favorite example of the latter is the Washington Post’s Compulsory Sterilization Provokes Fear, Contempt. It worried that the campaign produced too much backlash:

By forcibly sterilizing millions of men during the 20-month emergency, the government of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi may made some very limited inroads on the birthrate, but it probably set back by a generation all efforts to contain the exploding population of India.

The closest it comes to moral criticism is in a section on a populist politician who wanted to solve overpopulation through yoga:

While Narain's folksy approach fits generally into the government's roughly sketched plans for returning India to its peasant roots, some Western experts are skeptical that there can be anything like a voluntary solution to the crisis, especially under the constraints created by the emergency.

"Compulsory sterilization was an obscenity," said a West European economist. "But I'm afraid, I'm convinced that there's no way to cope with the population problem of this country if birth control is not made compulsory. There should at least be disincentives against having more than two children."

The article mostly focuses not on condemning or condoning, but on the war against “misinformation” - in the “peasant bitterness” around the sterilization campaigns, many poor Indians spread false rumors, like that sterilization could make them sick. Until the Indian government worked harder to fight these kinds of myths, it would never be able to meet sterilization quotas effectively.

Francis Galton had the good fortune to die before people started misusing his ideas, allowing us to hope he would have opposed such developments. Ehrlich is still very much alive. When asked in 2015 if he still agreed with everything in his book, he said that “I do not think my language was too apocalyptic in The Population Bomb. My language would be even more apocalyptic today. The idea that every woman should have as many babies as she wants is, to me, exactly the same kind of idea as everybody oughta be permitted to throw as much of their garbage into their neighbor’s backyard as they want.”

Luckily for Ehrlich, no one cares. He remains a professor emeritus at Stanford, and president of Stanford’s Center for Conservation Biology. He has won practically every environmental award imaginable, including from the Sierra Club, the World Wildlife Fund, and the United Nations (all > 10 years after the Indian sterilization campaign he endorsed). He won the MacArthur “Genius” Prize ($800,000) in 1990, the Crafoord Prize ($700,000, presented by the King of Sweden) that same year, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2012. He was recently interviewed on 60 Minutes about the importance of sustainability; the mass sterilization campaign never came up. He is about as honored and beloved as it’s possible for a public intellectual to get.

(meanwhile, in 2020 the University College of London, to worldwide acclaim, announed that they were “denaming” a building previously named for Galton to show their repugnance for his eugenic theories).

Francis Galton’s ideas led - without his support or consent - to several hundred thousand forced sterilizations. Paul Ehrlich’s ideas - with his full support and consent - led to several million forced sterilizations.

Adraste claims our society has a taboo around eugenics only because of its repugnance at coercive sterilization. But actually, our society can’t bring itself to care at all about coercive sterilizations at all when eugenics isn’t involved.

III.

Beroe: I claim that if eugenics is discredited because its morally bankrupt proponents forcibly sterilized people in its name, then environmentalism - whose morally bankrupt proponents forcibly sterilized ten times as many people in its name - should be ten times as discredited. The only reason they aren’t is that the failures of eugenics received enough public attention to generate a hyperstitious slur cascade against it, and the failures of environmentalism didn’t.

Adraste: That seems bonkers to me. It seems easy to draw a line between demanding that foreign dictatorships sterilize their populace - which would be evil whether or not it was done under the environmental aegis - and saving the whales, or ensuring clean water, or protecting the rainforest.

Beroe: And it seems easy to me to draw a line between demanding that mental hospitals sterilize their patients - which would be evil whether or not it was done under the eugenic aegis - and having a sperm bank for talented people, or providing financial incentives to reproduce. You’re trying to take refuge in the exact sort of distinctions you wanted to deny me, under the argument that the harmless ideas were a “slippery slope” towards the harmful ones. Once you start saving the whales, you’re implicitly accepting a worldview which questions the sustainability of industrial civilization. And that worldview is a risk factor for demanding that Indira Gandhi sterilize millions of Indians. I’m not asserting this, mind you - I love whales! - just trying to point out the hypocrisy of your position.

Adraste: I recognize the similarity between these two cases, but if you retreat from your pathological extreme Outside View for a second, I think a gestalt look at both movements would show that eugenics had many other failures, and environmentalism many other successes, and that it’s fair to use these as context when deciding how to legislate each particular case.

Beroe: What you call my “pathological extreme Outside View” is an attempt to ban myself from smuggling in all my prejudices under the guise of “context”. For example, someone with different biases than you might say eugenics had many successes - my favorite is Dor Yeshorim, the group that screens for the genetic mutations common in Ashkenazi Jews and makes sure that two carriers don’t marry each other and produce a child with a deadly condition. Or they might say environmentalism has had some pretty spectacular failures - knee-jerk environmentalist opposition to nuclear power prevented it from taking over from fossil fuels, leading to our current coal-and-oil-dominated regime and all the worries about climate change that come with it - also coal pollution in the air kills tens of thousands of people per year directly. I think that if you do your calculations and context-finding without writing the bottom line ahead of time, it’s actually quite hard to make environmentalism come out on top.

Adraste: So, what? So we should drink lead-filled water on purpose to own the libs? Or whoever it is you’re trying to own here, I must admit I’m having trouble keeping track.

Beroe: No! We can admit that “environmentalism” is a big tent containing both evil hurtful ideas and good valuable ideas, and that the evil hurtful ideas do not detract one whit from the goodness of the good valuable ideas. And then we can do the same with eugenics!

Adraste: I must admit you make a compelling point. But don’t you agree there is sometimes a place for slippery slopes? For example, it seems so attractive to hand over the government to a nice-seeming communist dictator with good ideas. Maybe he can use that absolute power to really fix things up! But if someone proposes this, I would like to be able to object that, in the past, “give all power to a nice-seeming communist who will use it for good things” has slipped down a slope to “the communist dictator is actually a bad guy and abuses his power”. And I would like to be able to make this argument without a certain dear friend objecting that it’s exactly the same as saying that if you let people save the whales, maybe they will end up sterilizing millions of Indians.

Beroe: You also make a compelling point. I cannot deny that past atrocities cast deontological shadows, making us wary of doing anything in their vicinity. Indeed, it seems like this is the origin of deontology, and all moral systems beyond a naive act utilitarianism - that sometimes our attempts to do good will end in evil, and so we shut off large categories of apparently-good things because they resemble those that have historically ending in evil more often than we expected. If I have any argument at all here, beyond a simple “well, my intuitions about whether to do this say no in this particular case”, it’s that we should rarely let an atrocity cast shadows over speech, belief, or opinion, because once we ban those things, we lose the capacity for self-correction. I may deny your right to save the whales, but I will defend to the death your right to argue that the whales should be saved without facing the least bit of social sanction for your views.5

IV.

Character views are not author views, but I will admit to agreeing with Beroe’s final paragraph above.

Footnotes

Although eugenics eventually became labeled racist, this took a while and before it happened the political coalitions were not what you would expect. The anti-racist positions of the 1920s, expressed by black leaders like W.E.B. DuBois, centered around fear that only white people would get to do eugenics to themselves, leaving the white race irrecoverably better than the black. Black organizations demanded that eugenics be applied to blacks as well, with many of them thinking of it as their ticket out of relative poverty. See eg Nuriddin and Ginther.

As far as I can tell, Galton had a reasonable 19th century view of genetics, making a few good guesses while also appreciating how little he knew. His successors were utterly and inexcusably confused about the topic, and conceptualized all negative traits as simple recessive genes; once these were were removed from the population by killing or sterilizing their carriers, nobody would have negative traits anymore. A grim reminder of how wrong they were: the Nazis killed nearly ever schizophrenic in Germany, hoping to eliminate “the schizophrenia gene”. Today, Germany has exactly as many schizophrenics as any other country, because there are thousands of genes involved in schizophrenia, and all the deleterious variants are present in some frequency in the healthy population. But see footnote 4 below.

This is eliding a lot of complexity in what Galton actually believed. Most of his published speeches focus on “positive eugenics” - convincing geniuses to breed more, rather than undesirables to breed less. He seemed to understand how little we knew about genetics, and wanted more research before doing anything rash (if the research had been done, it would have shown that most negative eugenic practices could not possibly have worked). But he also wrote an unpublished novel about a eugenic utopia, whose policies extended to social pressure for undesirables not to have children, and sometimes exile. There was no mention of forcible sterilization or murder. I am not an expert in Galton and he may have mentioned these somewhere else.

Adraste sticks to moral arguments against eugenics and never tries to claim it wouldn’t work; I don’t think arguments that it wouldn’t work are defensible. Nobody doubts that breeding programs can successfully enhance or remove traits from farm animals or dogs; nobody serious doubts anymore that most human traits are at least partly genetic. And Beroe specifically mentions sperm banks - I don’t think anyone seriously doubts that which sperm donor you choose affects your future child’s traits a lot, and the child of a Nobel Prize winner is about 100,000x more likely to win a prize themselves than the average person. Even if you doubt the existence of genes, eugenics should work on whatever alternative explanation you have for the clustering of traits within families. For example, if the reason poorer people have poorer children is educational access / culture / cycles of poverty, you should still expect that increasing the proportion of rich people to poor people having children would increase the proportion of rich people to poor people in the next generation. This doesn’t mean that a given proposal to change the gene pool might not need much more selection pressure / take much longer than expected (see footnote 2 above), but now that we understand genetics we can calculate this. Also, common sense goes a long way here - most people have a good idea how much more children resemble their parents than the average adult.

Coria: Oh, hello there! You always seem so surprised to see me, even though I always show up at times like this!

Adraste: Oh no, what kind of crazy galaxy-brained take do you have for us today?

Coria: I want to claim that, in expectation, Paul Ehrlich did nothing wrong. He thought a population explosion was going to end the world! In fact, he had good reason to think this - it was the natural continuation of the trends at the time, averted only by a Green Revolution outside the window of what most forecasters considered possible. If he had been right, mass sterilization would have been the only way to save the world.

We have a known system for dealing with times when you need to break deontological prohibitions for the greater good, which is you present your case to the government and let it be considered democratically. He did that, the government agreed, and everyone tried mass sterilization. They were all tragically wrong, of course, but if they’d been right it would have been the right thing to do. Ehrlich was stupid but not evil.

Beroe: You could justify anything with that!

Coria: Quite! For example, Galton was pretty sure that there was a dysgenic trend - the human race was getting sicker and dumber every generation, and would soon lose the ability to sustain complex societies. He was more careful than Ehrlich - unable to prove it, he didn’t exactly propose any solutions. But his successors did, they went through the proper legal channels, and they took extreme action to avert the collapse of civilization. Now, in fact Galton was almost as wrong as Ehrlich - modern research suggests the dysgenic trend does exist, but it’s only 1-3 IQ points per century - things will be very different long before we notice it. Still, even the counterfactual Galton who demanded full-speed ahead negative eugenics acted correctly based on what he knew at the time.

Beroe: So are you endorsing pure act utilitarianism?

Coria: Absolutely not. I’m only recommending the existence of governments, which has been standard practice since Gilgamesh. Many things are rights violations - for example, seizing someone’s property. But when a legitimate government does so in the public interest after due consideration, we accept it as part of living in a society. It was a rights violation to quarantine an entire population in their homes during the early days of the coronavirus. But the legitimate government decided to do it in order to protect the public interest, so it’s not morally equivalent to kidnapping or whatever we would call it if a random person did it. And some states still castrate pedophiles as a punishment - one which naturally includes sterilization - and I have no particular problem with that. So it seems I must believe governments may sometimes involuntarily sterilize citizens when it is in the public interest. Did you know the Supreme Court’s ruling on Buck said that “The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes?”

Beroe: Awkward.

Adraste: Yes, this is one of the very many things about the Buck ruling I would change if I had a time machine.

Beroe: So are you saying that governments can’t be judged on normal standards of good and evil? Everything Stalin did was okay, because he was dictator while he did it?

Coria: No, of course not. I’m saying that individuals are judged on a strictly deontological standard, and governments on something partway between deontology and consequentialism. During a crisis, governments are licensed - within the bounds of their constitutions - to act for the greater good. These acts can still be judged as evil, but only on consequentialist grounds - they made the world worse rather than better.

If the governments that followed Ehrlich had succeeded in averting a population bomb that would otherwise have destroyed humanity, I would judge them as good. If the governments that followed Galton had succeeded in preventing a dysgenic collapse of civilization, I would judge them as good too. Instead, their actions caused great suffering for no benefit, so I judge them as bad.

Adraste: I thought you said Ehrlich did nothing wrong!

Coria: I said bad, not wrong. If you see your friend and hug them, but unbeknownst to you they have an aneurysm which is activated by hugs, and they die, then you have done a thing which went badly, but you were not morally in the wrong for doing it. Ehrlich did the best he could have based on what he knew at the time. If we are to do better than him, it will have to be by being smarter, not by being more moral.

Adraste: I find this pretty concerning. My original position is that we must taboo everything about eugenics. Beroe made an argument that perhaps we could relax the taboo if we promise never to do anything unethical or coercive. But she hasn’t even had time to gather her breath before you come in and say that in fact, we should sometimes do unethical and coercive things too. I think this just reinforces my suspicion that we shouldn’t even take that first step.

Coria: That’s fine. You have every right to oppose eugenics, but you must exercise that right in your capacity as a citizen of a democratic polity, not as some sort of impersonal arbiter of morality who gets to decide prima facie what actions are always and forever off limits. Paul Ehrlich estimated that what was best for the world was to pursue a sterilization campaign, and he lobbied the government for it. If you estimate that what’s best for the world is to never do sterilization campaigns, you should also lobby the government for that. I will believe both of you are good people trying to do the right thing as you understand it. Only one of you can be right, of course, but that reflects on your intelligence, not your morality. We can’t all be geniuses. At least not until Beroe gets her Nobel Sperm Bank!

I (Scott) definitely do not admit to agreeing with Coria’s final paragraph, but I admit the problem bothers me: it seems hard to find a middle ground between Coria’s stance and pure minarchist libertarianism.

Share this post