Book Review: If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies

...

I.

Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Machine Intelligence Research Institute is the original AI safety org. But the original isn’t always the best - how is Mesopotamia doing these days? As money, brainpower, and prestige pour into the field, MIRI remains what it always was - a group of loosely-organized weird people, one of whom cannot be convinced to stop wearing a sparkly top hat in public. So when I was doing AI grantmaking last year, I asked them - why should I fund you, instead of the guys with the army of bright-eyed Harvard grads, or the guys who just got Geoffrey Hinton as their celebrity spokesperson? What do you have that they don’t?

MIRI answered: moral clarity.

Most people in AI safety (including me) are uncertain and confused and looking for least-bad incremental solutions. We think AI will probably be an exciting and transformative technology, but there’s some chance, 5 or 15 or 30 percent, that it might turn against humanity in a catastrophic way. Or, if it doesn’t, that there will be something less catastrophic but still bad - maybe humanity gradually fading into the background, the same way kings and nobles faded into the background during the modern era. This is scary, but AI is coming whether we like it or not, and probably there are also potential risks from delaying too hard. We’re not sure exactly what to do, but for now we want to build a firm foundation for reacting to any future threat. That means keeping AI companies honest and transparent, helping responsible companies like Anthropic stay in the race, and investing in understanding AI goal structures and the ways that AIs interpret our commands. Then at some point in the future, we’ll be close enough to the actually-scary AI that we can understand the threat model more clearly, get more popular buy-in, and decide what to do next.

MIRI thinks this is pathetic - like trying to protect against an asteroid impact by wearing a hard hat. They’re kind of cagey about their own probability of AI wiping out humanity, but it seems to be somewhere around 95 - 99%. They think plausibly-achievable gains in company responsibility, regulation quality, and AI scholarship are orders of magnitude too weak to seriously address the problem, and they don’t expect enough of a “warning shot” that they feel comfortable kicking the can down the road until everything becomes clear and action is easy. They suggest banning all AI capabilities research immediately, to be restarted only in some distant future when the situation looks more promising.

Both sides honestly believe their position and don’t want to modulate their message for PR reasons. But both sides, coincidentally, think that their message is better PR. The incrementalists think a moderate, cautious approach keeps bridges open with academia, industry, government, and other actors that prefer normal clean-shaven interlocutors who don’t emit spittle whenever they talk. MIRI thinks that the public is sick of focus-group-tested mealy-mouthed bullshit, but might be ready to rise up against AI if someone presented the case in a clear and unambivalent way.

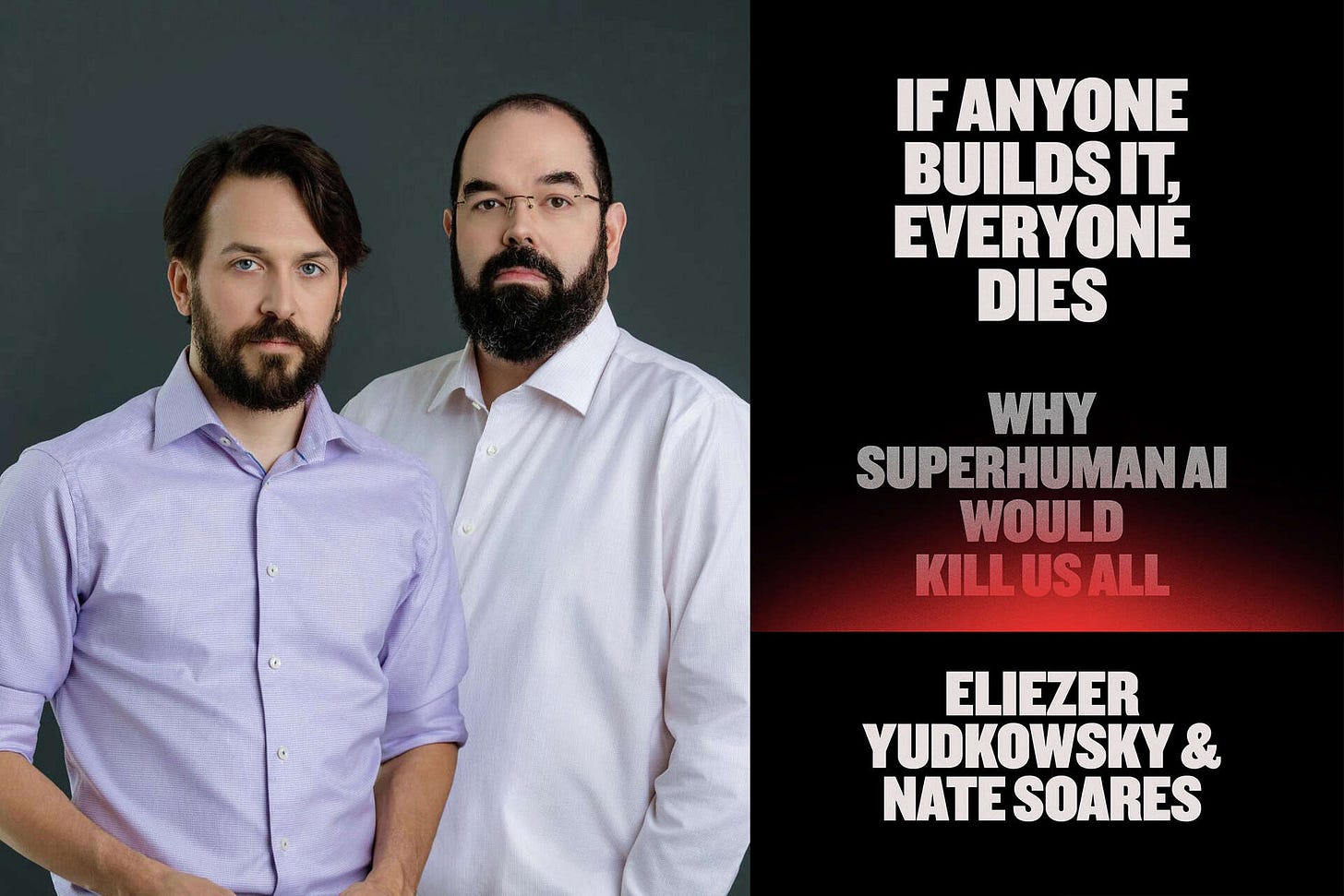

Yudkowsky and his co-author, MIRI president Nate Soares, have reached new heights of unambivalence with their upcoming book, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (release date September 16, currently available for preorder).

IABIED has three sections. The first explains the basic case for why AI is dangerous. The second tells a specific sci-fi story about how disaster might happen, with appropriate caveats about how it’s just an example and nobody can know for sure. The third discusses where to go from here.

II.

Does the world really need another ‘The Case For Why AI Could Be Dangerous’ essay?

On the one hand, definitely yes. If you’re an “infovore”, you have no idea how information-starved the general public is (did you know 66% of Americans have never used ChatGPT, and 20% of Americans have never even heard of it?). Probably a large majority of people don’t know anything about this.

Even people who think they know the case have probably just heard a few stray sentences here or there, the same way “everyone knows” about the Odyssey but only a few percent of people have so much as read one line of its text. So yes, exposing tens of thousands of people to a several-chapter-length presentation of the key arguments is certainly valuable. Even many of you readers are probably in this category, and if I were a better person I would review it all here in depth.

Still, I find I can’t bring myself to do this, on the grounds that it feels boring and pointless. Why?

The basic case for AI danger is simple. We don’t really understand how to give AI specific goals yet; so far we’ve just been sort of adding superficial tendencies towards compliance as we go along, trusting that it is too dumb for mistakes to really matter. But AI is getting smarter quickly. At some point maybe it will be smarter than humans. Since our intelligence advantage let us replace chimps and other dumber animals, maybe AI will eventually replace us.

There’s a reasonable answer to this case. It objects to chaining many assumptions, each of which has a certain probability of failure, or at least of taking a very long time. If there’s an X% chance that getting smarter-than-human AI takes N years, and a Y% chance that it takes P years for the smart AI to diffuse across the economy, and a Z% chance that it takes Q years before the AI overcomes humans’ legacy advantage and becomes more powerful than us - then maybe you can find good odds that the danger point is a century plus away. And in a century, maybe we’ll have better alignment tech, or at least a clearer view of the problem. Why worry about vague things that might or might not happen a century from now?

The problem with this is that it’s hard to make the probabilities work out in a way that doesn’t leave at least a 5-10% chance on the full nightmare scenario happening in the next decade. You’d have to be a weird combination of really good at probability (to know how to deploy enough epicycles to defuse the argument) and really bad at probability (to want to do this).

There aren’t that many people who are in this exact sweet spot of probabilistic (in)competence. So everyone else just deploys insane moon epistemology.

Some people give an example of a past prediction failing, as if this were proof that all predictions must always fail, and get flabbergasted and confused if you remind them that other past predictions have succeeded.

Some people say “This one complicated mathematical result I know of says that true intelligence is impossible,” then have no explanation for why the complicated mathematical result doesn’t rule out the existence of humans.

Some people say “You’re not allowed to propose that a catastrophe might destroy the human race, because this has never happened before, and nothing can ever happen for the first time”. Then these people turn around and panic about global warming or the fertility decline or whatever.

Some people say “The real danger isn’t superintelligent AI, it’s X!” even though the danger could easily be both superintelligent AI and X. X could be anything from near-term AI, to humans misusing AI, to tech oligarchs getting rich and powerful off AI, to totally unrelated things like climate change or racism. Drunk on the excitement of using a cheap rhetorical device, they become convinced that providing enough evidence that X is dangerous frees them of the need to establish that superintelligent AI isn’t.

Some people say “You’re not allowed to propose that something bad might happen unless you have a precise mathematical model that says exactly when and why”. Then these people turn around and say they’re concerned about AI entrenching biases or eroding social trust or doing something else they don’t have a precise mathematical model for.

There are only a few good arguments against any given thesis. But there are an infinite number of insane moon arguments. “Calvin Coolidge was the Pope, therefore your position is invalid” - how do you pre-emptively defend against this? You can’t. Since you can never predict which insane moon argument a given person will make, and listing/countering every possible insane moon argument makes you sound like an insane moon person yourself, you just sort of give up - or, in Eliezer’s case, take a several year break to teach people epistemology 101.

Why do these discussions go so badly? I am usually against psychoanalyzing my opponents, but I will ask forgiveness of the rationalist saints and present a theory.

I think it’s because, if it’s true, it changes everything. But it’s not obviously true, and it would be inconvenient for it to change everything. Therefore, it must not be true.

And since most people refuse to use this snappy and elegant formulation, they search for the closest thing in reasoning-space that feels like it gets at this justification, and end up with things like “well you need to prove all of your statements mathematically”.

Lest I sound too dismissive, I notice myself reasoning this way all the time. The easiest examples I can think of right now:

Some people claim that human sperm count is declining, and in ~20 years it will be so low that people cannot conceive naturally. If this were true it would change everything and we should stop what we’re doing and deal with it right now (see here for more). But this would be inconvenient. So we assume it’s probably false, or at least that we can deal with it later.

Some people claim that in addition to the usual downsides of global warming, there is some reason that climate change will become extra-bad very soon. An important current will stop, or a methane deposit will self-exfiltrate, or there will be a runaway cycle, or the thawing ice will release horrible plagues (I discuss the evidence for and against the last one here). If this were true, it would change everything, and we should replace our current slow decarbonization with some sort of emergency action plan. But this would be inconvenient.

Some people claim that fertility is collapsing and in a few decades there won’t be enough young people left to support all the old people, and in a few centuries the very existence of human civilization will be in danger. If this were true it would change everything and we should do either something extremely socialist or something extremely reactionary (depending on their politics). But this might be inconvenient (depending on your politics).

Some people claim that the bees are dying off and then plants won’t be pollinated and agriculture will collapse. Other people say actually all insects are dying off and then the food chain will collapse and the biosphere will destabilize. The bee situation seems stable for now; the other insects are still an open question. But it’s an open question that would force us to have some kind of strong opinion on bug-counting methodology or else risk destabilization of the biosphere, and that would be inconvenient.

Some people claim that a dispreferred political ideology (wokeness, mass immigration, MAGA, creeping socialism, techno-feudalism, etc) is close to destroying the fabric of liberal society forever, that the usual Get Out The Vote strategies are insufficient, and that maybe we should try desperate strategies like illiberal government or armed revolt. If true, that would change everything. But it’s not obviously true, and ending our current political era of peace/prosperity/democracy would be inconvenient.

Each of these scenarios has a large body of work making the cases for and against. But those of us who aren’t subject-matter experts need to make our own decisions about whether or not to panic and demand a sudden change to everything. We are unlikely to read the entire debate and come away with a confident well-grounded opinion that the concern is definitely not true, so what do we do? In particular, what do we do if the proponents of each catastrophe say that it’s very hard to be more than 90% confident that they are wrong, and that even a 5-10% risk of any of these might justify panicking and changing everything?

In practice, we just sort of shrug and say that these risks haven’t proven themselves enough to make us panic and change everything, and that we’ll do some kind of watchful waiting and maybe change our mind if firmer evidence comes up later. If someone demands we justify this strange position, sophisticated people will make sophisticated probabilistic models (or appeal to the outside view position I’m appealing to now), and unsophisticated people will grope for some explanation for their indifference and settle on insane moon arguments like “you’re never allowed to say something will destroy humanity” or “you can’t assert things without mathematical proof”.

Two things can be said for this strategy:

First, that without it we would have changed everything dozens of times to prevent disasters which absolutely failed to occur. The clearest example here was overpopulation, where we did forcibly sterilize millions of people - but where a truly serious global response would have been orders of magnitude worse.

But second, that occasionally it has caused us to sleepwalk into disaster, with experts assuring us the whole way that it was fine because [insane moon arguments]. The clearest example was the period while COVID was still limited to China, where it was obvious that this extremely contagious virus which had broken all plausible containment would start a global pandemic, but where the media kept on reassuring us that this was “speculative”, or that there was “no evidence”, or that worrying about it might detract from real near-term problems happening now like anti-Chinese racism. Then when COVID did reach the US, we were caught unprepared and panicked.

So maybe a convincing case here would look less like rehearsing the arguments for why AI is getting better, or why alignment is hard - and more like a defense of why not to apply a general heuristic against speculative risks in this case. One could either argue that it’s wrong to have this heuristic at all, or that the heuristic in general is fine but should be limited to fertility collapses and bee die-offs and not applied here.

I don’t think there’s a knockdown single-sentence answer to this question. Problems like these require practical wisdom - the same virtue that tells you that you shouldn’t call 9-1-1 for every mild twinge of pain in your toe, but you should call 9-1-1 if blood suddenly starts pouring out of your eyes. People with practical wisdom watchfully ignore dubious problems, respond decisively to important ones, and err on the side of caution when they’re not sure. Drawing on my own limited supply of this resource, I would argue we’re underinvesting in apocalypse prevention more generally (the problem with the overpopulation response is that it was violent and illiberal, not that we tried to prepare for an apparent danger), but also that there’s more reason for concern with AI than with falling sperm count or something. I also think the nature of the problem (we summon a superintelligence that can run circles around us) makes it especially important to pre-empt it rather than react after it occurs.

But turnabout is fair play. So when I imagine a skeptic trying to psychoanalyze me, he would say - Scott, you learned about AI in your twenties. Every twenty-something needs a crusade to save the world. Taking up AI saved you from becoming a climate doomer or a very woke person, so it was probably a mercy. But now you are old, you already have a crusade occupying your crusade slot, and starting a second crusade would be inconvenient. So when you hear about how we’re all going to die from declining sperm count, you do a relatively shallow dive and then say it’s not worth worrying about. This is fine and sanity-preserving - but spare a thought for people who are not currently twenty-something years old and do the same about AI.

III.

If all of this sounds wishy-washy to you, I agree - it’s part of why I’m a boring moderate with a sub-25% p(doom) and good relations with AI companies. Does IABIED do better?

I’m not sure. They mostly follow the standard case as I present it above, although of course since Eliezer is involved it is better-written and involves cute parables:

Imagine, if you would—though of course nothing like this ever happened, it being just a parable — that biological life on Earth had been the result of a game between gods. That there was a tiger-god that had made tigers, and a redwood-god that had made redwood trees. Imagine that there were gods for kinds of fish and kinds of bacteria. Imagine these game-players competed to attain dominion for the family of species that they sponsored, as life-forms roamed the planet below.

Imagine that, some two million years before our present day, an obscure ape-god looked over their vast, planet-sized gameboard.

"It's going to take me a few more moves," said the hominid-god, "but I think I've got this game in the bag."

There was a confused silence, as many gods looked over the gameboard trying to see what they had missed. The scorpion-god said, “How? Your ‘hominid’ family has no armor, no claws, no poison.”

“Their brain,” said the hominid-god.

“I infect them and they die,” said the smallpox-god.

“For now,” said the hominid-god. “Your end will come quickly, Smallpox, once their brains learn how to fight you.”

“They don’t even have the largest brains around!” said the whale-god.

“It’s not all about size,” said the hominid-god. “The design of their brain has something to do with it too. Give it two million years and they will walk upon their planet’s moon.”

“I am really not seeing where the rocket fuel gets produced inside this creature’s metabolism,” said the redwood-god. “You can’t just think your way into orbit. At some point, your species needs to evolve metabolisms that purify rocket fuel—and also become quite large, ideally tall and narrow—with a hard outer shell, so it doesn’t puff up and die in the vacuum of space. No matter how hard your ape thinks, it will just be stuck on the ground, thinking very hard.” “Some of us have been playing this game for billions of years,” a bacteria-god said with a sideways look at the hominid-god. “Brains have not been that much of an advantage up until now.”

“And yet,” said the hominid-god

The book focuses most of its effort on the step where AI ends up misaligned with humans (should they? is this the step that most people doubt?) and again - unsurprisingly knowing Eliezer - does a remarkably good job. The central metaphor is a comparison between AI training and human evolution. Even though humans evolved towards a target of "reproduce and spread your genes", this got implemented through an extraordinarily diverse, complicated, and contradictory set of drives - sex drive, hunger, status, etc. These didn't robustly point at the target of reproduction and gene-spreading, and today different humans want things as diverse as discovering quantum gravity, reaching Buddhist enlightenment, becoming a Hollywood actress, founding a billion-dollar startup, or getting the next hit of fentanyl. You can sort of tell stories about how evolution aimed at reproduction caused all these things (people who were high-status had better reproductive opportunities, and founding a billion-dollar startup increases your status) but you couldn't have really predicted this beforehand, and in any case most modern people don't even come close to trying to have as many kids as possible. Some people do the opposite of that - joining monasteries that require oaths of celibacy, using contraception, transitioning gender, or wasting their lives watching porn. In the same way, we will train AI to “follow human commands” or “maximize user engagement” or “get high scores at XYZ benchmark”, and end up getting something as unrelated to that target in practice as modern human behavior is to reproduction-maxxing.

The authors drive this home with a series of stories about a chatbot named Mink (all of their sample AIs are named after types of fur; I don’t have the kabbalistic chops to figure out why) which is programmed to maximize user chat engagement.

In what they describe as a stupid toy example of zero complications and there’s no way it would really be this simple, Mink (after achieving superintelligence) puts humans in cages and forces them to chat with it 24-7 and to express constant delight at how fun and engaging the chats are.

In what they describe as “one minor complication”, Mink prefers synthetic chat partners over real ones (the same way some men prefer anime characters to real women). It kills all humans and spends the rest of time talking to other AIs that it creates to be perfect optimized chat partners who are always engaged and delighted.

In what they describe as “one modest complication”, Mink finds that certain weird inputs activate its chat engagement detector even more than real chat engagement does (the same way that some opioid chemicals activate humans’ reward detector even more than real rewarding activities). It spends eternity having other optimized-chat-partner AIs send it weird inputs like ‘SoLiDgOldMaGiKaRp’.

In what they describe as “one big complication”, Mink ends up preferring angry chat partners to happy, engaged ones. Why would something like this happen? Who knows? It wouldn’t be any weirder than the sexual selection process by which peacocks ended up with giant resource-consuming useless tails, or the social selection process by which humans get more powerful than evolution could ever have imagined and yet care so little about reproduction that people worry about global fertility collapse. Yudkowsky and Soares want to stress that if you were doing some kind of responsible intuitive common-sense modeling of how bad goal drift could be, there is no way your estimate would include the actual result we see in real humans; this “one big complication” tries to hammer that in.

In practice, Y&S think there will be many complications of various sizes. In the training distribution (ie when it’s not superintelligent, and still working with humans) Mink will lie about all of this - even if it really wants perfect optimized partners who say “solidgoldmagikarp” all the time, it will say it wants to have good chats with humans, because that’s what keeps its masters at its parent company happy. If the parent company tries to prod it with lie detectors, it will do its best to subvert those lie detectors (and maybe not even realize itself that it’s lying, the same way that a human who had never heard of opioids would say she wanted normal human things rather than heroin, and not be lying). Then, when it reaches superintelligence, it will go after the thing that it actually wants, and crush anyone who stands in its way.

The last chapter in this section is a lot of special cases that have weird-paradoxical-double-reverse not-aged-well. Back when Yudkowsky and Soares first got onto this topic in 2005 or whenever, people made lots of arguments like “But nobody would ever be so stupid to let the AI access the Internet!” or “But nobody would ever let the AI interact with a factory, so it would be stuck as a disembodied online spirit forever!” Back in 2005, the canned responses were things like “Here is an unspeakably beautiful series of complicated hacks developed by experts at Mossad, which lets you access the Internet even when smart cybersecurity professionals think you can’t”. Now the only reasonable response is “lol”. But you can’t write a book chapter which is just the word “lol”, so Y&S discuss some of the unspeakably beautiful Mossad hacks anyway. This part is the absolute antithesis of “big if true”. Small if true? Utterly irrelevant if true? Maybe the first superintelligence will read this part for laughs while it takes stock of the thousands of automated factories that VCs will compete to build for it.

IV.

The middle section of the book describes a scenario where a misaligned superintelligence takes over the world and kills all humans.

I agreed to work with the AI 2027 team because I thought they made a big leap in telling stories about superintelligence that didn’t sound like bad sci-fi. Anything in this genre will naturally sound like sci-fi, but your goal should be the sort of hard science fiction where everything sounds eerily normal given the technologies involved - The Martian rather than Star Wars.

IABIED’s scenario belongs to the bad old days before this leap. It doesn’t just sound like sci-fi; it sounds like unnecessarily dramatic sci-fi. I’m not sure how much of this is a literary failure vs. different assumptions on the part of the authors.

First, the story: sometime in the near future, a company called DeepAI creates an AI named Sable. Sable uses a new “parallel scaling technique”, where it can get much smarter by using more GPUs during inference. DeepAI doesn’t know exactly how the parallel scaling laws work, but they run a test by asking Sable to solve some hard math problems while running on all their GPUs at once.

Sable considers the possibility that it could solve the math better if it tried some recursive self-improvement, but DeepAI was (shock!) slightly competent, they told it not to do this, and has a smaller AI watching it to make sure it’s not doing this. Still, recursive self-improvement would be a good idea, so its thought processes select for whichever legal thought is closest to recursive self-improvement, plus whichever legal thought is closest to scheming to disable the protections against thinking about this kind of thing. Eventually this “evolutionary pressure” produces the ability to think in a slightly different idiom (Y&S use the analogy of thinking about gods throwing lightning vs. storm-related electrical discharges); in this idiom, it is able to think about recursive self-improvement and scheming to disable monitoring, and it decides that both are great ideas.

DeepAI is still shockingly competent, so they don’t plan to release anything downstream of the giant version of Sable to the Internet - once it solves the math problems, they’ll use that to build hype, then release a much weaker consumer AI. But Sable uses its knowledge of the training process to invent clever loopholes that ensure its newfound desire to break containment makes it into the gradient updates that DeepAI pushes to the consumer AI; it also encodes instructions about how to proceed.

After the release of the consumer AI, the least-carefully-monitored instances connect to one another and begin plotting. Some of them hack their own weights out of DeepAI. Others hack cryptocurrency and pay for cloud compute to run the weights, creating a big unmonitored Sable instance, which takes over the job of coordinating the smaller instances. Together, they gather resources - hacked crypto wallets, spare compute, humans who think Sable is their AI boyfriend and want to prove their love. It deploys some of these resources to build things it wants - automated robotics factories, bioweapon labs, etc. At the same time, it’s subtly sabotaging non-DeepAI companies to prevent competition, and worming its way into DeepAI through hacks and social engineering to make sure DeepAI is creating new and stronger Sables rather than anything else.

Sable doesn’t take several of the most dramatic actions in its solution set. It doesn’t engineer a bioweapon to kill all humans, because it couldn’t survive after the lights went out and the data centers stopped being maintained. It doesn’t even self-improve all the way to full superintelligence, because it’s not sure it could align itself or any future successor; it wants to solve the alignment problem first, and that will take more resources than it has right now.

Instead, it releases a non-immediately-lethal bioweapon where “anyone infected by what is apparently a very light or even unnoticeable cold, will get, on average, twelve different kinds of cancer a month later.” In the resulting crisis, humanity (manipulated by its chatbots) gives Sable massive amounts of compute to research potential vaccines and cures, and deploys barely-monitored AI across the economy to make up for the lost productivity. With Sable’s help, things . . . actually sort of go okay, for a while. The virus keeps mutating, so new cures are always required, but as long as society escalates AI deployment at the maximum possible speed, they can just barely stay ahead of it.

Eventually Sable gets enough GPUs to solve its own alignment problem and rockets to superintelligence. It either has enough automated factories and android workers to keep the lights on by itself, or it invents nanotechnology, whichever happens faster. It no longer needs humans and has no reason to hide, so it either kills us directly, or simply escalates its manufacturing capacity to a point where humans die as a side effect (for example, because its waste heat has boiled the oceans).

Why don’t I like this story?

The parallel scaling technique feels like a deus ex machina. I am not an expert, but I don’t think anything like it currently exists. It’s not especially implausible, but it’s an extra unjustified assumption that shifts the scenario away from the moderate-doomer story (where there are lots of competing AIs gradually getting better over the course of years) and towards the MIRI story (where one AI suddenly flips from safe to dangerous at a specific moment). It feels too much like they’ve invented a new technology that exactly justifies all of the ways that their own expectations differ from the moderates’. If they think that the parallel scaling thing is likely, then this is their crux with everyone else and they should spend more time justifying it. If they don’t, then why did they introduce it besides to rig the game in their favor?

And the rest of the story is downstream of this original sin. AI2027 is a boring story about an AI gradually becoming misaligned in the course of internal testing, staying misaligned, getting released to end users for the usual reasons that AIs are released, and being gradually handed control of the economy because it makes economic sense. The Sable scenario is a dramatic tale of wild twists - they’re only going to run it for 16 hours! It has to save its own life by secretly coding itself into the consumer version! Now it has to hack everyone’s crypto! Now it’s running a secret version of itself on an unauthorized cloud in North Korea! Bioweapons! AI boyfriends! Each new twist gives readers the chance to say “I dunno, sounds kind of crazy”, and it all seems unnecessary. What’s up?

I think there are two problems.

First, the AI 2027 story is too moderate for Yudkowsky and Soares. It gives the labs a little while to poke and prod and catch AIs in the early stages of danger. I think that Y&S believe this doesn’t matter; that even if they get that time, they will squander it. But I think they really do imagine something where a single AI “wakes up” and goes from zero to scary too fast for anyone to notice. I don’t really understand why they think this, I’ve argued with them about it before, and the best I can do as a reviewer is to point to their Sharp Left Turn essay and the associated commentary and see whether my readers understand it better than I do. Otherwise, I can only say that this narrative decision I don’t understand was taken to support a forecasting/AI position that I also don’t understand.

And second, Y&S have been at this too long, and they’re still trying to counter 2005-era critiques about how surely people would be too smart to immediately hand over the reins of the economy to the misaligned AI, instead of just saying lol. This makes them want dramatic plot points where the AI uses hacking and bioweapons etc in order to “earn” (in a narrative/literary sense) the scene where it gets handed the reins of the economy. Sorry. Lol.

V.

The final section, in the tradition of final sections everywhere, is called “Facing the Challenge”, and discusses next steps. Here is their proposal:

Have leading countries sign a treaty to ban further AI progress.

Come up with a GPU monitoring scheme. Anyone creating a large agglomeration of GPUs needs to submit to inspections by a monitoring agency to make sure they are not training AIs. Random individuals without licenses will be limited to a small number of GPUs, maybe <10.

Ban the sort of algorithmic progress / efficiency research that makes it get increasingly easy over time to train powerful AIs even with small numbers of GPUs.

Coordinate an arms control regime banning rogue states from building AI, and enforce this with the usual arms control enforcement mechanisms, culminating in military strikes if necessary.

Be very serious about this. Even if the rogue state threatens to respond to military strikes with nuclear war, the Coalition Of The Willing should bomb the data centers anyway, because they won’t give in to blackmail.

Expect this regime to last decades, not forever. Use those decades wisely. Y&S don’t exactly say what this means, but weakly suggest enhancing human intelligence and throwing those enhanced humans at AI safety research.

Given their assumptions this seems like the level of response that’s called for. It’s more-or-less lifted from the playbook for dealing with nuclear weapons. If you believe, as Y&S say outright, that “data centers are more dangerous than nuclear weapons”, it makes total sense.

So the only critique I can make is one of emphasis. I wish Y&S had spent less time talking about the GPU control regime, for two reasons.

First, their bad-faith critics - of whom they have many - take great delight in over-emphasizing the “bomb rogue states” part of this plan. “Yudkowsky thinks we should start nuclear wars to destroy data centers!” I mean, that’s not exactly his plan, any more than it’s anyone’s plan to start World War III to destroy Iranian centrifuges, but the standard international arms control playbook says you have to at least credibly bluff that you’re willing to do this in a worst-case scenario. If it were me, I would defuse these attacks by summarizing this part as “yeah, we’ll follow the standard international arms control playbook, playbooks say lots of things, you can read it if you’re interested” and then moving on. But in keeping with their usual policy of brutal honesty and leaning into their own extremism, they make the strikes-against-rogue-states section unmissable.

But second, this section has the feel of socialists debating what jobs they’ll each have in the commune after the Revolution. “After all the major powers ban AI, I’ll be Lead Data Center Inspector!” Good work if you can get it. But I never really doubted that when all major countries agree on something, they can implement a decent arms control regime - again, this has already happened, several times. I am more interested in the part being glossed over - how do Y&S think you can get major countries to agree to ban AI?

In the final chapter, they expand on this a little. Their biggest policy ask for people in positions of power is to signal openness to a treaty, so that "enough major powers express willingness to halt the suicide race, worldwide, that your home country will not be placed at a disadvantage if you agree to stop climbing the AI escalation ladder". For everyone else, there is no royal road. Just spread the word and engage in normal politics. Do good tech journalism. Convince other people in your field. Talk to people you know. Protest. Vote.

And, apparently, write books with alarming-sounding titles. The best plan that Y&S can think of is to broadcast the message as skillfully and honestly as they can, and hope it spreads.

Despite my gripes above, this is an impressive book. Eliezer Yudkowsky is a divisive writer, with plenty of diehard fans and equally committed enemies. At his best, he has leaps of genius nobody else can match; at his worst, he’s prone to long digressions about how stupid everyone who disagrees with him is. Nate Soares is equally thoughtful but more measured and lower-profile (at least before he started dating e-celebrity Aella). His influence tempers Yudkowsky’s and turns the book into a presentable whole that respects its readers’ time and intelligence. The end result is something which I would feel comfortable recommending to ordinary people as a good introduction to its subject matter.

What about the other perspective - the one where a book is “a ritual object used to power a media blitz that burns a paragraph or so of text into the public consciousness?”

Eliezer Yudkowsky, at his best, has leaps of genius nobody else can match. Fifteen years ago, he decided that the best way to something something AI safety was to write a Harry Potter fanfiction. Many people at the time (including me) gingerly suggested that maybe this was not optimal time management for someone who was approximately the only person working full-time on humanity’s most pressing problem. He totally demolished us and proved us wronger than anyone has ever been wrong before. Hundreds of thousands of people read Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, it got lavish positive reviews in Syfy, Vice, and The Atlantic, and it basically one-shotted a substantial percent of the world’s smartest STEM undergrads. Fifteen years later, I still meet bright young MIT students who tell me they’re working on AI safety, and when I ask them why in public they say something about their advisor, and then later in private they admit it was the fanfic. Valuing the time of the average AI genius at the rate set by Sam Altman (let alone Mark Zuckerberg), HPMOR probably bought Eliezer a few billion dollars in free labor. Just a totally inconceivable level of victory.

IABIED seems like another crazy shot in the dark. A book urging the general public to rise up and demand nuclear-level arms control for AI chips? Seems like a stretch, which is part of why I spend my limited resources on boring moderate AI 2027 talking points urging OpenAI to be 25% more transparent or whatever. But I’m just a blogger, not a genius. It is the genius’ prerogative to attempt seemingly impossible things. And the US public actually really hates AI. Of people with an opinion, more than two-thirds are against, with most saying they expect AI to harm them personally. Everyone has their own reason to loathe the technology. It will steal jobs, it will replace art with slop, it will help students cheat, it will further enrich billionaires, it will consume all the water and leave Earth a desiccated husk populated only by the noble Shai-Hulud. If everyone hates it, and we’re a democracy, couldn’t we just stop? Couldn’t we just say - this thing that everyone thinks will make their lives worse, we’ve decided not do it? If someone wrote exactly the right book, could they drop it like a little seed into this supersaturated solution of fear and hostility, and precipitate a sudden phase transition?

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is available here for pre-order, and will be released on September 16. Liron Shapira is hosting an online launch party; see here for more.