Your Book Review: Two Arms and a Head

Finalist #7 in the Book Review Contest

[This is one of the finalists in the 2024 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

Content warning: body horror, existential devastation, suicide. This book is an infohazard that will permanently alter your view of paraplegia.

The Death of a Newly-Paraplegic Philosopher

For me, paraplegia and life itself are not compatible. This is not life, it is something else.

In May of 2006, philosophy student Clayton Schwartz embarks on a Pan-American motorcycle trip for the summer before law school. He is 30 years old and in peak physical condition.

He makes it as far south as Acapulco in Mexico before crashing into a donkey that had wandered into the road.

The impact crushes his spinal cord at the T5 vertebra, rendering him paralyzed from the nipples down.

On Sunday, February 24, 2008, he commits suicide.

In the year and a half in between, he writes Two Arms and a Head, his combination memoir and suicide note.

Writing under the pseudonym Clayton Atreus, he lays out in excruciating detail how awful it is to be paralyzed, and how his new life is but a shadow of what it once was. He concludes that his life is no longer worth living, and proceeds to end it.

Along the way, he addresses the obstacles that society has put in his way of dying on his own terms—the biggest of which is the fact that physician-assisted suicide for his condition is illegal at the time.

But there are other factors. Smaller, more insidious roadblocks. Our society doesn't just condemn suicide; we do a great disservice to newly disabled patients in refusing to let them voice their misery and grief about being disabled. The book is a scathing indictment of how our society enables the lifelong disabled at the expense of the newly disabled and terminally ill.

Looking back from ~15 years in the future, when we have a patchwork of states and countries that have legalized physician-assisted suicide, Clayton's story stands as a cautionary tale for why it must become—and stay—legal.

Being Paralyzed Sucks

As a student of philosophy, Clayton is heavily influenced by the writings of Nietzsche and Camus. He analyzes the experience of being paralyzed primarily through the lens of Existentialism. It’s hard to imagine a more apt philosophy for interpreting body horror.

Two Arms and a Head comes from one of those rare moments in history when an individual’s circumstances so perfectly intersect with their skills that they leave a mark on the world. What better cosmic tragedy than to have a strong, fit, arrogant philosophy buff suddenly find himself paralyzed? His memoir is an exploration of what it means to exist in a body that is no longer entirely his own.

The full ramifications of being paralyzed are rarely discussed in polite company. Rest assured, he omits no details:

Everything below my nipples is no longer me. Hence the title of this work, “Two Arms and a Head”. [...] I am two arms and a head, attached to two-thirds of a corpse. The only difference is that it’s a living, shitting, pissing, jerking, twitching corpse. [...] What was once my beloved body is now a thing. [...]

Two arms and a head. Period. Additionally, I will be using a sort of shorthand in this book when I refer to parts of “my” body. So when I say “my penis”, for instance, what I really mean is “the unfeeling, alien piece of flesh that used to be my penis, but is now just part of the living corpse I will push or drag around forever until I am dead.” [...]

As far as I feel about my body, who do you love more than anyone else in the world? Think of that person. Now picture being chained to their bloated corpse—forever.

No, Really, It's Way Worse Than You Think

I had limited exposure to paraplegics until I read this book. Growing up, I only knew them from pop culture—usually as side characters who would appear on Very Special Episodes of Saturday morning cartoons. Professor X. The glider kid from that one episode of Avatar. The main character from the other Avatar.

The tropes gave me a mental model of being paraplegic that boiled down to "you can't use your legs, so you have to drag yourself in and out of a wheelchair to use the toilet. But you're still an ordinary person sitting upright in a wheelchair."

Clayton wastes no time in dispelling this myth:

> I am devastatingly, cataclysmically physically disabled. [...]

> There is a tremendous difference between me and an able-bodied person sitting in a wheelchair. Tremendous.

Spinal cord injuries affect everything downstream of the injury—not just "the legs" but also the pelvis, bowels, genitals, and abdomen. Depending on where the injury occurs, that can include all the trunk muscles that keep someone sitting upright.

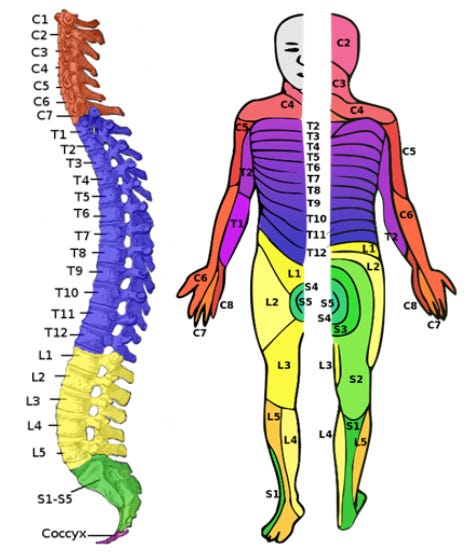

Starting at the top, the cervical (neck) vertebrae control the head, neck, arms, and fingers. The thoracic (torso) vertebrae control the entire torso and abdomen. The lumbar (lower back) vertebrae control the hips and front muscles of the legs. The sacral (tailbone) vertebrae control the back muscles of the legs and the groin area. The very last vertebra, S5, innervates the anus and genitals.

Clayton is injured quite high up on the torso at the T5 vertebra. Let's consider the ramifications of having everything below the nipples be completely numb and limp.

To start off, that means that he has no use of the muscles that hold him upright.

Nothing keeps me sitting up—no hip flexors, erector spinae, hamstrings, or abdominal muscles. I am arms-and-a-head on a column of Jell-O.

He can't put both arms out in front of him, lest he fall over. He has to continuously prop himself up with one arm while doing anything at arm's length. After only 1.5 years of being paralyzed, this has already caused significant repetitive strain injuries in his elbows, shoulders, and ulnar nerves.

Clayton still has to deal with all the logistics of life, despite two-thirds of his body being a hunk of corpse-flesh. He dedicates huge swaths of the text to all the little time-wasting tasks he now has to do. How much of his life is ticking away with every delay, every piece of effort, every task that is trivial for an able-bodied person but monstrously difficult for him. Something as simple as getting out of a car is an entire production—let alone running errands, cleaning, doing laundry, cooking.

Since the lower two-thirds of his body no longer sends pain signals to his brain, he must proactively tend to all of its physical needs. Complications include pressure sores, infections, and a high chance of blood clots. Aside from suicide, the leading causes of death among paraplegics are all related to poor circulation.

In addition to the loss of conscious sensation and muscle control, problems with the autonomic nervous system—heart rate, orthostatic blood pressure, temperature regulation—are common. This is even more pronounced in cervical spine (neck) injuries. Some quadriplegics black out or the blood rushes to their head when being moved from lying down into reclining in a wheelchair. A spinal cord injury wreaks havoc on the body's functioning.

Go back to that diagram. The groin area is innervated by the very end of the spinal cord, at the S5 vertebra. We tend to think of our legs as being “below” the crotch, but the nerves that control bowel movements and urination are downstream of the ones for the legs.

To keep the party rolling I will tell you about piss and shit. [...] To urinate I have to slide a catheter down my urethra. [...] To defecate I finger myself up the ass and root around and around until the shit comes out. Nuggets, smooshy, whatever it is I’m digging in it.

He describes the disgusting, nauseating process at length. For the sake of your lunch, I will refrain from quoting it all.

In addition to being unable to open and close his sphincters on command, he also receives no signals of needing to go. If he eats the wrong thing and gets a bout of diarrhea, he will have no warning—no abdominal discomfort and no final urge to rush to the bathroom.

One afternoon he "has an accident" while lounging on his couch. In trying to move from the couch to the toilet, he subsequently smears feces all over the couch, the carpet, his wheelchair, the toilet seat, and the shower.

After he digs the poop out of his anus and washes himself off, he then has to clean all of that up by himself.

From a wheelchair.

Bending down, stretching, trying not to fall over, trying to reach the floor to scrub feces off the carpet.

From a wheelchair.

This episode was hardly the first time. He would routinely wake up in the morning to find that he had soiled himself overnight. Imagine struggling to rip dirty sheets off the bed, stuff them in the laundry, and put a clean sheet on the mattress—from a wheelchair.

I don't know about you, but I can barely get a fitted sheet on my own mattress, and I get to do it while standing up.

And unless I want to piss or shit myself, there can be no rest from this drudgery, ever, for the rest of my life. No relieving stretch of time without piss-dowsing and fingering myself up the asshole.

Nobody told Kid Me that Professor X has to dig turds out of his anus every day.

The groin dysfunction doesn't stop there.

To be redundant once more, I can’t feel my penis. [...] Men, think how losing your penis would make you feel. Ladies, think of having your clit amputated and never having sex again. [...]

True, the unfeeling penis attached to the living corpse I drag around can become erect but what has that to do with me?

The one time he tries to have intercourse after his injury, it goes about as well as you'd expect:

Watching a woman bob up and down on the penis attached to the corpse that used to be my body struck me as macabre and disturbing. It was like necrophilia. It’s like watching a woman get off by rubbing my amputated foot on herself.

The disturbing facts just keep on rolling.

One final note about the physical symptoms: spinal cord injuries hurt. Everything below the damage is numb, but the injury itself is a massive tear in the central nerve that controls the body.

The pain is insistent, nagging, and so sharp it seems to crackle. [...] It’s just as sharp and intense every time, over and over, like it’s mocking you. Sometimes it happens when I’m lying in bed and it’s like trying to fall asleep with someone sticking a needle between my ribs or the bones of my big toe.

But, surely, the only real problem is the physical limitations? Clayton is still the same person he'd always been, right? He has the same brain, same personality he did before the accident. Even if he can't walk anymore, he still has his memories.

Not so fast.

Yes, Even Worse Than That

What kind of mental and emotional toll does all of this take on Clayton?

The feeling I experience is a frantic, frenzied, desperate distress. [...] I need to move. I need to move. [...]

Not only is two-thirds of my body paralyzed, but so is a huge part of my innermost self. It wants more than anything to feel and experience life. To exist. But it exists now only in a place between reality and nothingness with no hope of ever coming back. [...] All it can do is degenerate in the solitary place it has been forever exiled to.

A popular heuristic in neuroscience is "use it or lose it." This is usually in the context of memorization, but it also applies to sensory organs and limbs. When Clayton is injured, his brain's connection to everything below his nipples is severed. Lacking any more sensory input from down there, the brain simply overwrites and repurposes the unused neurons.

His injury is not limited to his present and future, but also reaches back into his past:

Certain of my memories seem to be disappearing. For example, when I try to remember doing things that involved running, jumping, and sex, the memories seem less real or vivid than they used to. [...]

If I imagine taking another person’s hand in mine, or kissing someone’s face, or someone touching my face, I feel something similar to sensation in those parts of my body when I imagine it. [...] But my lower body is now just a void, and its death started the creation of a void in my brain. Not only can I not feel it, but my ability to imagine feeling it is disappearing, as is my capacity to remember feeling it, and doing things with it.

He likens himself to a Cartesian brain, a part of the world but outside of it, forever locked away, unable to exert his will on the outside world. Not only has he lost his legs; he is beginning to lose the memory of those legs, too. Everything he ever was, any skills that he ever learned related to being able-bodied, are destined to die over the coming years.

His mind is doomed to slowly decay as its neurons do what neurons do: rewrite themselves until none of the person he used to be is left.

Toxic Positivity

Can Clayton actually talk about any of these things with his peers?

Not really. He has a small circle of other recently paralyzed friends who understand, but outside of that, no.

American culture has an entire social ecosystem that reinforces the idea that disabled people should be upbeat and optimistic about their life prospects. Almost any interview with a paraplegic ends on some upbeat note about how their disability "doesn't stop them from doing all the things they want to do" and that "they can do anything” an able-bodied person can.

In fact, Two Arms and a Head opens with one such quote from Stephen Hawking:

“I try to lead as normal a life as possible, and not think about my condition, or regret the things it prevents me from doing, which are not that many.” —Stephen Hawking

This is patently absurd. Why do they say these things? Do they actually mean it, or are they just being hyperbolic for rhetorical effect? Surely they all know, secretly, that they’re lying to themselves?

Clayton argues that no, they mean it, and they’re not lying to themselves.

Remember how disability affects the brain? How all those unused neurons get repurposed, and any concepts of using those paralyzed limbs gets overwritten (if they ever existed in the first place)?

They [lifelong paraplegics] tend to only see life in terms of the possibilities that exist for them [...] Their view becomes somewhat tautological. “What I can do is all that is possible, therefore I can do all that is possible.”

Just as able-bodied people cannot comprehend what it’s like to be a paraplegic, lifelong paraplegics and quadriplegics simply cannot grasp what it is to be able-bodied. I’m not saying that lightly. The difference is biological. They have different brains. [...] They do not understand the experience of being able-bodied—neither the subtleties or much of what, to observers, is overt and glaring. They can try to imagine it, but they don’t even come close to comprehending the potential that exists there.

Hence the common refrain that there are “not many” things that they can’t do.

Adding to this dynamic is that it is considered impolite in our culture to call them out on it:

If I were still able-bodied and a paraplegic told me he could do everything I could, I would just think “Looks like being crippled fucked up his mind too, because that’s insane.” I’m not sure what I’d actually say to him, but I know it wouldn’t be that. [...] So the disabled are basically allowed to go around saying whatever on Earth they want. They acquire a kind of de facto moral infallibility because nobody is going to argue with them.

On top of this, humans have a basic need to belong, stay positive, and avoid people who are negative and miserable. If paraplegics were honest about all the body horror and misery, they would quickly find themselves devoid of friends.

So what is a newly paraplegic person to do in order to maintain connections during a time in their life when they desperately need comfort and support?

Brainwash themselves, of course!

Clayton was staring down the prospect of what he would have to do to his mind in order to survive in our current society as a paraplegic. It was bad enough to be mutilated physically; he didn't also want to be mutilated mentally.

What happened to my body is frightful, but no less than what happens to the minds of many disabled people. We have to have some kind of integrity to our views of the world and reality, and the more the better. [...] So my unwillingness to adopt certain “attitudes” or whatever people call them is something like a desperate struggle to evade the clutches of madness.

It gets worse. This does not just affect their social lives and beliefs. These dynamics ripple out into the medical community’s attitudes about paraplegia. If every interviewee swears that paralysis doesn’t hold them back in life, then why pour resources into finding a cure?

I’ve heard people say that spinal cord injury is not a priority for medical research like cancer because “people can live like that”. No, we can’t live like this. This is not “life”.

Which raises the question—have there been any breakthroughs since 2008?

The State of the Cure

Let’s take a short break from the existential horror to look at the science of spinal cord injuries.

Clayton killed himself in 2008 because there was no cure at the time. Have there been any new developments in the ~15 years since?

The short and upsetting answer is "not yet"—though there are some glimmers of hope.

Why are Spinal Cord Injuries So Hard to Fix?

The spinal cord consists of multiple concentric layers of nerve fibers, not unlike an electrical cable. Wherever the spinal cord has trauma, the nerve cells die off and form lesions of scar tissue that block all nerve signals from traveling downstream of whichever thread was damaged. Some patients are lucky in that only parts of the spinal cord are damaged, resulting in paralysis on only one side of the body.

Nerve cells in the spinal cord do not regenerate themselves. Once damaged and scarred, there’s nothing anyone can do.

The good news is that emergency medicine has come a long way in arresting the formation of scar tissue at the moment of injury. Patients coming into the ER today have a much better prognosis than they did a few decades ago. The interventions are straightforward treatments like stabilizing the spine, surgery to release pressure on the pinched nerves, and shots of corticosteroids to reduce swelling and inflammation.

But beyond that, there is no clinically-proven, FDA-approved treatment for an existing injury. Clayton describes the challenge of rebuilding his injury as something similar to “reconstructing a crushed strawberry.” No amount of stabilization would have put his smeared spinal cord back together.

The Latest Research

Treatments fall into two camps: bridging the injury, and encouraging the injured scar tissue nerves to regenerate.

Implanted Nerve Cells

In 2012, Prof. Geoffrey Raisman's team at University College London successfully treated a paralyzed man in Poland.

The treatment involved removing one of the olfactory bulbs in his brain in order to culture olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs), which are the only nerve cells in the human body that continuously regenerate. The surgeons removed a section of nerve from the patient's ankle, then implanted both the ankle nerve and the OECs into his spine at the injury site. The grafted tissue bridged the gap between his brain and the healthy spinal cord just below the injury.

After years of rehab and physical therapy, in 2014 the researchers announced their success to impressive fanfare. As of 2016, the patient could walk, ride a tricycle, and had regained bladder, bowel, and sexual function. He was far from his pre-injury self, but his quality of life had improved immensely compared to before the treatment. The call went out to recruit two more volunteers for another study.

And then... crickets.

This follow-up study has yet to be performed.

It could have been delayed for a number of reasons. Perhaps they never found suitable volunteers whose profiles satisfied the demands of European regulators. Perhaps Brexit threw a bureaucratic wrench in the collaboration between UCL and the research center in Poland. Perhaps they ran out of funding.

To make matters worse, Prof. Raisman passed away in 2017.

In the years since, the team has been making progress in fits and starts. As of 2022, the current focus at UCL has been on figuring out how to culture OECs from the nasal mucosa instead of needing to crack open the skull to get at the olfactory bulbs directly. They’ve also made improvements in the technique for applying these cells to the injury site. Things are certainly happening, albeit at a glacial pace.

This treatment strategy may become widespread in the future, but at the moment, it remains experimental.

NervGen's "Wiggling Molecules"

In 2021, NervGen Pharma announced a drug that encourages damaged spinal tissue to heal without scarring. A bioengineered molecule, NVG-291, is injected into the spinal cord and acts as a scaffold for the nerve cells to attach to as they regrow. The molecules of this scaffold naturally "wiggle” and stimulate nearby nerve cell receptors, promoting healing. Animal models were extremely promising.

NVG-291 is currently in Phase 1b/2a clinical trials, which are scheduled to start in August of 2024.

I’m cautiously optimistic. The main impediments to finding a cure are the same ones that plague any other field of medical research: lack of funding and unreasonable requirements from regulators. The main problems at this point in time appear to be bureaucratic rather than strictly biological.

Will any of this research pan out within the next 5, 10, or even 20 years? Maybe. Only time will tell. (Someone should start a prediction market about this!)

Alas, this is all coming too late to have saved Clayton.

The Decision to Die

I am absolutely and heartbreakingly in love with life. But this is not life. [...]

For those who like to say this one: “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.” I reply that suicide in my case is a permanent solution to a permanent problem. [...] I have only one serious problem in life and it’s being paralyzed.

Clayton does not come to this decision lightly. He considers it exhaustively and systematically. When deciding whether to keep living, he starts from the premise that there is some amount of suffering past which life stops being worth it. He evaluates where that dividing line is by examining the sources of meaning in his life.

He starts by asserting that there is nothing wrong with his mental health or his reasoning abilities:

I am not depressed, I am tortured, and there is a difference. [...] If they came up with the cure today and I got better instantly, I could win myself a Nobel Prize in medicine for proving that depression was caused not by anything in the brain as previously thought, but by damage to a few cubic centimeters of nervous tissue in the spinal cord. Because I guarantee I’d pop up and be feeling as merry as a lark in about one second. [...] My problem is not depression. [...]

There is no problem with my reasoning powers. [...] So if I say, “Paraplegia prevents me running. A life without running is not worth living. Therefore, my life is not worth living.” you might not agree with one of my premises, but there is no question of whether I’m being reasonable.

This is similar to Frankl’s argument in Man’s Search for Meaning, and in fact Clayton spends an entire section talking about Frankl. He has a few disagreements with the book, but he has no gripe with the core message. Clayton decides to die because he had meaning in his life—and then the accident took it all away:

Probably the life of a deaf man would be good enough for me, or that of a mute or a man missing a leg or an arm. But not the life of a paraplegic. There is not enough left for me. [...]

The life I dreamed of and loved with all my heart is gone forever and there is nothing I can do about it. And it’s not just slightly changed, but utterly devastated. [...] My skills as a carpenter, roofer, plumber, gardener, all devastated. My ability to conduct my everyday life with wonderful efficiency, devastated. The wonderful way I was able to relate to other people, devastated. My sex life, devastated. My social life, devastated. [...]

I am who I am, I love what I love, and given what I need from life, existence is no longer tenable for me.

Some readers may look at that list and call him shallow. Even if that were so, that doesn't change his argument. Maybe most people don't place having sex, controlling one's bowels, and running through the woods as the quintessence of life-affirming values, but I'd be willing to bet that they're still important.

Reading this book should prompt a moment of introspection. If you disagree with Clayton’s list above, then reflect on what does give your life meaning. No, seriously, make a list: family, friends, partners, children, hobbies, skills, etc. Write them down.

Cross out one entry at random. How would you feel if you lost that entry? Would you still have enough left over to carry on? Probably.

Now cross out a few more. Lose your partner. Lose your children. Lose your parents. Your siblings. Your best friend. Your favorite hobby. How do you feel? Still worth it?

Add in some physical negatives: chronic pain. Constant nausea every time you eat. Losing feeling and control of your bowels, your legs, your genitals, your diaphragm, your non-dominant hand, your dominant hand, both arms. What about loss of sight? Hearing? Speaking? Communicating at all?

What about ending up like the title character in Johnny Got His Gun, where he is left with no legs, no arms, and is rendered blind, deaf, and mute? What would life be like as a disconnected brain in almost complete sensory deprivation?

How much would you have to lose before your life stops being worth living?

That list—and the dividing line between "worth it" and "not"—is different for everyone. The decision to end one's life is deeply personal. Clayton happened to draw the line at a particular point. Others may agree or disagree, but Clayton’s judgment was his own.

Decision in hand, next comes the hard part.

The Roadblocks

I did not want much from the world in dying. To be able to put my affairs in order without fear of being taken prisoner and treated like I was insane. To say goodbye to those I loved without the same fear. To die a painless death without worrying about leaving behind something gruesome. And to be comforted as I died. When a person has absolutely nothing left and is facing annihilation, all he wants is not to be alone.

For Clayton, killing himself is not a simple matter. At the time only one US state, Oregon, had any kind of “Death With Dignity” law on the books. However, this law only allowed assisted suicide for terminally ill patients with less than six months to live, while Clayton’s condition was stable.

The slightest whisper of suicidal ideation would have gotten him locked up in the psych ward. He has to write his book in secret, he has to lay his thoughts out for the world in secret, and he has to die in secret.

Becoming paralyzed destroys him on two fronts—the disability itself, and the fact that he is completely, utterly, devastatingly alone with his feelings. He writes Two Arms and a Head because he needs to show the world how agonizing it is to face death alone and how important it is for physical-assisted suicide to become—and stay—legal.

How empty to exist in this universe and share your feelings and experience with nobody! But that is how you, the world, have left me to die, alone. But what you don’t realize is this: in turning your backs on me, you have turned your backs on yourselves. [...]

Someday you will be on your deathbed and maybe you will remember me. What I say to the world is that if you don’t do something about the way death and assisted suicide are dealt with, you may someday find yourselves in an unimaginably horrible situation with no way out. [...]

Beware! There could be a horrible fate waiting for you and if you don’t all get together, look each other in the eye, recognize the insanity, and change the laws, you could wake up tomorrow as a head on a corpse with no way out for the next thirty years.

A lingering question you might be asking is: if he cared so much about it, then why didn’t he become an activist to get it legalized? The Overton Window was shifting. Washington state would pass a bill a few months after his death, and it would be legalized in Montana by a court case in 2009. Several more states would follow suit in the mid-2010s. He could have shared his experiences far and wide and joined the burgeoning movement that existed back then. He was a law student at Vanderbilt for crying out loud; surely he could have enlisted the help of at least a couple of his colleagues?

No one but him could have answered that, though I suspect that the answer is because he didn’t want to. He found his existence to be so ghastly that he didn’t want to stay in it for a second longer than necessary. The only reason he lasted as long as he did was because he wanted to finish the book. He chose to leave Two Arms and a Head as his legacy for the world, and nothing more.

We’ve gone over the state of the cure over the last ~15 years. Has there been any progress on amending the laws for physician-assisted suicide?

The State of MAiD

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) is currently legal in a patchwork of countries and US states.

The exact rules, restrictions, and methods vary. In most places that have legalized it, the patient’s condition must be considered terminal (i.e. death is expected within six months) to be eligible for MAiD. The procedure itself is typically either an IV injection administered by a nurse, or a prescription cocktail of benzodiazepines, digoxin, and opioids which patients drink themselves.

In Canada and the Netherlands, MAiD is also available to patients with a disability that does not present as immediately terminal. The Netherlands currently includes severe treatment-resistant mental illness as a qualifying condition, and Canada will follow suit in 2027.

So it sounds like Clayton got his wish, at least in Canada and parts of Europe. Now, when a Canadian ends up in a terrible accident, they have a choice in the matter of whether they want to spend the next few decades as a quadriplegic head-on-a-corpse. Phew.

However, it’s not all smooth sailing. It seems like every few months there’s another horror story in the press coming out of Canada or Europe. Two news stories came out in quick succession in late March/early April 2024—one from Canada, the other from the Netherlands.

In Canada, a 27-year-old autistic woman with no disclosed physical symptoms was granted the right to proceed with MAiD by an Alberta court. The story broke after her father sued to try and stop her.

In the Netherlands, a 28-year-old woman has decided to pursue MAiD due to her treatment-resistant clinical depression and borderline personality disorder. Her MAiD is scheduled for sometime in May 2024. At the time of this writing, she has yet to undergo it.

These stories are nothing new. They certainly sound dreadful.

Diving into every big story from the last ten years would be beyond the scope of this review, but let’s return to the one about the 27-year-old autistic Canadian woman who was granted MAiD. Both the Calgary Herald and CBC framed the story as a grieving father desperately trying to prevent his autistic daughter from being led astray by unethical doctors cherry-picked by the Alberta Health Service. The father insists that his adult daughter is physically healthy, albeit “vulnerable and not competent” to make medical decisions due to her autism and ADHD. Despite this, the judge has allowed MAiD to proceed anyway.

Meanwhile, reading the actual court decision shows that the legal issue at hand is whether the woman is required to disclose the physical ailment(s) that led to two doctors approving MAiD. The judge ruled that the woman is competent to make her own medical decisions, and that she is not required to disclose her diagnosis to either her family or the court. The father has since filed an appeal.

(July 2024 Update: the appeal hearing was subsequently scheduled for October 7, 2024 - six months in the future. Not willing to wait that long, the woman began a voluntary stoppage of eating and drinking (VSED) on May 28. The hearing was rescheduled for June 24. However, the woman continued to refuse food and water going into June. The father withdrew his appeal on June 11. It is unknown whether the woman has undergone MAiD at this time of this update.)

She is not choosing MAiD because of autism or ADHD. We don’t know what her physical diagnosis is. We only have the father’s insistence that “her physical symptoms, to the extent that she has any, result from undiagnosed psychological conditions.” That’s the father’s words, not a physician’s, and not the patient’s. Neurodivergence does not bestow immunity against all the nasty ailments that can cut someone down in their twenties.

I’m not accusing every news piece about MAiD of being similarly sensationalized, but I’m not not accusing every MAiD story of being similarly sensationalized.

Despite so many of these stories not holding up to their headlines, many remain opposed to the expanded rules. There is a massive contingent of activists who want to keep MAiD illegal.

Not Dead Yet

Clayton had a particular amount of ire directed at one prominent anti-MAiD disability rights org: Not Dead Yet.

Not Dead Yet (NDY) was founded in 1996 by the same people who lobbied to get the Americans with Disabilities Act passed a few years prior. As the name implies, they reject the notion that death could ever be an acceptable response to living with a disability.

Like any activist org worth their salt, they have a convenient Talking Points page where they lay out all the reasons why they’re opposed to MAiD. They argue that MAiD is deadly discrimination against disabled patients, with current programs having insufficient safeguards to prevent foul play. NDY argues against a medical field that has decided that death is preferable to disability. They insist that they are not against individual autonomy; patients will always be free to commit “un-assisted” suicide if they truly wish to die.

The page opens by explaining that MAiD is necessarily a disability issue, even in places where MAiD is only available to the terminally ill.

Although people with disabilities aren’t usually terminally ill, the terminally ill are almost always disabled.

When terminally ill patients get polled on why they are choosing MAiD, it turns out that avoiding pain isn’t the primary motivation. In Oregon, where MAiD is only available for the terminally ill, every patient fills out a questionnaire when they apply for the program. Tallying up all the surveys from 1998–2023, to top reasons are:

“Losing autonomy” (90%)

“Less able to engage in activities” (90%)

“Loss of dignity” (70%)

“Losing control of bodily functions” (44%)

“Burden on family” (47%)

“Inadequate pain control, or concern about it” (29%)

“Financial implications of treatment” (7%)

The top five all relate to the disabling symptoms that come with dying. “Less able to engage in activities” sounds remarkably similar to Clayton’s reasoning of, “the things that gave my life meaning are no longer possible, therefore it’s time to die.”

This isn’t surprising when considering that palliative care is legal in all 50 states. If someone’s condition is judged to be terminal, as Oregon requires, they already get a bottomless supply of morphine. Pain is not really the problem anymore.

The problem is that a failing body is, well, failing. Patients become weak and frail. They struggle to walk and use the bathroom. They may become dependent on a feeding tube or a respirator. Somewhere along the way they might lose their minds to dementia. All of these are serious, debilitating symptoms that can suck the meaning out of life, so many patients choose to die before they get to that point.

Not Dead Yet condemns this status quo.

We Don’t Need To Die to Have Dignity

In a society that prizes physical ability and stigmatizes impairments, it’s no surprise that previously able-bodied people may tend to equate disability with loss of dignity. This reflects the prevalent but insulting societal judgment that people who deal with incontinence and other losses in bodily function are lacking dignity. People with disabilities are concerned that these psycho-social disability-related factors have become widely accepted as sufficient justification for assisted suicide.

They argue that patients and physicians are merely reflecting a “prevalent but insulting” prejudice when they decide that death is preferable to debility. NDY paints a picture of the type of physicians who provide MAiD to patients:

In judging that an assisted suicide request is rational, essentially, doctors are concluding that a person’s physical disabilities and dependence on others for everyday needs are sufficient grounds to treat them completely differently than they would treat a physically able-bodied suicidal person. [...]

Legalized assisted suicide sets up a double standard: some people get suicide prevention while others get suicide assistance, and the difference between the two groups is the health status of the individual, leading to a two-tiered system that results in death to the socially devalued group. This is blatant discrimination.

There’s a lot to unpack here. NDY is starting from the premise that the desire to end one’s life is always and necessarily the product of an irrational mind, Claytons of the world be damned. Medical professionals, given that they’ve sworn an oath to protect life, have an obligation to treat all suicidal ideation with “suicide prevention” care (i.e. involuntary commitment until the patient comes to their senses).

A society that has legalized MAiD still extends this preventive care to the able-bodied who want to die, but then turns around and gladly assists disabled patients in ending their lives. This is discrimination! Doctors are murdering the undesirables!

To drive the point home, the Canadian chapter of NDY has this image on their homepage:

Clayton counters this by pointing out that doctors give different treatments for different circumstances all the time.

For example, begging for opioids out of the blue is considered “drug seeking” and will get you referred to addiction treatment; begging for opioids while in the ER for a severed leg... will get you opioids. Refusing to provide opioids and instead providing “addiction prevention care” to the able-bodied is not discrimination against the legless.

The Canadian chapter of Not Dead Yet has a similar Talking Points page, with this one written in the style of an FAQ. They raise some concerns about a lack of safeguards to prevent foul play. In Canada and parts of the United States, a MAiD patient simply picks up the lethal cocktail at a pharmacy, then takes it home to drink.

No witness is required when the drugs are taken. There’s no way to ensure that it’s voluntary.

If something goes wrong, there’s no way to help the person.

A lethal dose of drugs may sit around the house for weeks or months.

...That’s concerning. I didn’t know any of that before I read the website.

An obvious solution to this problem would be to do what the Netherlands does and require a medical professional to be present. That way, said clinician can ensure that the patient gives affirmative consent with no abuser standing over the patient’s shoulder. Once the patient has passed, the clinician can pack up the leftover meds for safe disposal. In the Netherlands, these professionals are part of dedicated teams who travel to patient homes for exactly this purpose.

Except NDY does not suggest this. In fact, they do the opposite. NDY condemns the Dutch approach by referring to these clinicians as members of a “mobile euthanasia unit” that dispatches patients in their own homes.

Everything seems to circle back to blaming doctors. But why?

Ableism

Underpinning Not Dead Yet’s objections to MAiD is the belief that society has a prejudice against disabilities. This prejudice is so strong that the average person believes that being disabled is sufficiently miserable to justify death. The disability rights community has a name for this bigotry: ableism.

Ableism is: “A system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness.”

When Clayton concludes that his paraplegic life is less “valuable” than his pre-accident life, he is invoking the societally constructed premise that “being able to walk, have sex, and control one’s bowel movements are good and desirable traits.” That is indeed one of his core values, and he is indeed being ableist.

The anti-ableist framework holds that a value judgment like “being able to walk, have sex, and control one’s bowel movements are good and desirable traits” is arbitrary bigotry on par with “having white skin is a good and desirable trait.”

When disability activists argue that our society should reject ableism, what they are saying is that we should reject the notion that “being able to walk, have sex, and control one’s bowel movements are good and desirable traits.”

Given what Clayton has told us of his life, that argument is cosmically, outlandishly insane.

So... why do they make it? What’s going on? They can’t really believe this, can they?

The knee jerk response is to dismiss them as just being in denial, but Clayton offers a much more horrifying explanation: they do mean it.

I have no desire to begrudge other paraplegics their happiness, though many of them evidently have every desire to begrudge me my feelings. I find them monstrous and inhuman the moment they want to insist that my feelings indicate from some kind of defect within me. [...] A clam is comfortable in its shell and thinks all of the other animals should envy it. A clam does not see why an eagle would rather die than be a clam.

Let’s explore this with a thought experiment.

The Four-Armed Alien

You probably don't fantasize on a daily basis about what life would be like with four arms. If you really try, you could imagine a few ways that life would be easier:

You could chop ingredients with two hands and stir the skillet with a third.

You could hold a 2x4 in place with two hands while holding and driving in a nail with the other two.

You could carry a full bundle of groceries with three arms while fumbling for the keys with the fourth.

That sure sounds convenient, doesn't it? Wouldn't that be so freaking awesome now that you really think about it?

But despite the possibilities, you don't dwell on it every day, because... you don't have four arms. You have two.

Our wiring just isn't cut out for this. And that's perfectly normal! Everyone's brain does this. This isn't some character flaw. Our brains simply aren't meant to comprehend sensory input from body parts that we don't have.

But suppose there existed a hypothetical alien race that did have four arms. One such alien’s entire experience of having four arms would be so much more detailed than human imagination. The convenience would be effortless, automatic. The feats of dexterity would be so mundane as to escape notice.

Now let's say that one of these aliens gets in an accident and has to get two arms amputated. They would be devastated! They would notice all the myriad things—both big and small—that they suddenly could no longer do. Their life would be immensely harder. Things that were effortless before would now be massive hurdles:

Vegetables must be chopped separately, with the existing food lying in the skillet, about to burn.

That 2x4 must be held up with one hand/forearm awkwardly pinning the board to the wall, while trying to awkwardly hold the nail in place so the other arm can swing the hammer.

That heavy bundle of groceries must be held precariously with only one hand as the other one fumbles for the keys.

The real list wouldn't be confined to those three entries, oh no. It would go on, and on, and on.

This amputee would be grieving the life that they used to have—and they might even conclude that their new life is not worth living. Other four-armed aliens might even agree. Their entire alien society might be filled with medical professionals who nod solemnly in understanding, give them info on how to put their affairs in order, and write a prescription for a deadly cocktail. When the time comes to drink it, the alien drifts off peacefully, surrounded and supported by all of their four-armed relatives.

Us two-armed humans might look at this and be outraged: "What!? What do you mean my two-armed life isn't good enough for you? Are you saying that I should die, too? You asshole!"

A lot of people stop right there. They call the alien shallow and bigoted against two-armed humans. They claim that the alien’s values are borne of small-minded prejudice, they condemn the aliens’ medical practices as barbaric, and they might even launch a campaign to get the practice outlawed and the alien doctors arrested.

But then, for some others, another thought creeps in: "...What if having four arms really is that good? Maybe my life is that much worse, and I don't even know it because my brain cannot fathom what I am missing. But tons of other amputees say that they're devastated and missing so much... Holy cow, should I die? Aaaaaaaah—"

This can quickly spiral into an existential crisis. (Don't do that! That's bad!)

If this happens to you, then please, to the best of your ability, try to take a step back and understand that this is not about you. It’s ok to have two arms.

When confronted by a two-armed alien amputee who wants to die, a “meaning-based” response would be to argue that yes, while having only two arms can be inconvenient, they still have some things they can do and some sources of meaning left. It's not all doom and gloom, and it is possible to lead a life that is "good enough" with two arms instead of four. That's a straightforward case to make.

The extra step here is if you fail to persuade the patient, then you can’t force them to comply. If the patient still concludes that their life is not worth living to them, then you have to respect their choice and let them die with dignity.

We don’t see disability activist groups like Not Dead Yet doing this. Instead, they get stuck on the “Are you saying I should die, too? You asshole!” stage, and then demand that all patients who want to die be sent to the psych ward.

But... why!? The sensible argument is sitting right there. Why don’t they use it?

Clayton argues that lifelong disabled activists don’t adopt this framework because it would require acknowledging that some factors related to bodily functioning can make life better or worse.

In other words, it requires accepting ableism.

In order to argue that a patient still has enough meaning left for life to be worth it, one has to first admit that not having a functioning body is Bad, Actually. An honest conversation with a newly disabled person requires arguing that the good outweighs the bad, not that the bad doesn’t exist.

Clayton points out that if someone has been disabled their whole lives, then their disabled life is just “life”. The limitations of their bodies are as mundane and mildly annoying as the problems that we face when we only have two arms instead of four. Digging turds out of their anus every day is just a part of life, like brushing one's teeth. Of course ableism sounds like unfounded bigotry on par with racism to them; they have no other frame of reference.

When lifelong disabled activists insist that there is nothing “inferior” about being disabled, they mean it. When they declare that patients are merely being prejudiced when they choose to die rather than live while disabled, they mean it. They are not in denial. Their brains literally cannot fathom what they are missing. No brain can.

Remember this next time you encounter an activist in a comment section under a sensational news story criticizing MAiD. When they dismiss patient fears about the dying process as unfounded bigotry, this is where they’re coming from.

Un-Assisted Suicide

The final argument that anti-MAiD proponents fall back on is that anyone can just commit suicide; why do they need help from doctors?

The glaringly obvious answer is: because patients cannot “just” commit suicide.

Clayton could not “just” ask for help putting his affairs in order. He could not “just” say goodbye to his loved ones. He could not “just” die peacefully without anyone trying to stop him. He could not “just” publish his memoir before his death—not if he wanted to avoid being committed.

Young people would prefer not to think about such things, but what everyone does not see is that those old people are you. You are them, it’s just a matter of time.

Until we defeat death in the glorious transhumanist future, it’s coming for all of us. Some of us may die suddenly in a tragic accident. Some may be diagnosed with a terminal illness that kills in a matter of months.

But most of us will die by very slow decay.

The counterfactual world—where the elderly are kept alive as shriveled husks for years, slowly withering away—is gruesome and ghastly.

Someday, you, too, may be on your deathbed at the end of your life, in extreme debility, but without any obvious physical ailment that will kill you quickly without medical intervention. Or at any moment, you, too, could get in an accident and become as horribly maimed as Clayton. The patients who choose MAiD today will be you tomorrow.

Those. People. Are. You.

So... Should You Read This Book?

If you can handle the body horror, it is worth reading. It helps to be familiar with Nietzsche, Existentialism, and the broader disability rights community/anti-ableism ideas.

But it’s not for the faint of heart.

In terms of the writing quality, Clayton would have benefited from an editor. For obvious reasons, he couldn’t make his work public until after his death, and it’s a real shame. The writing is, at times, disjointed and riddled with typos. It’s short for a book—only 66,000 words—but it probably could have been cut down by a third and organized into more clear sections.

Clayton’s biting, blunt, crass, and vitriolic style may be off-putting to some readers. His pre-injury self strikes me as a serious dudebro; I would not have wanted to be his friend had we met in real life.

If nothing else, reading the full experience certainly gave me an appreciation for my bowel functioning.

If you’re feeling courageous, you can read Two Arms and a Head online here.

The Road to Nowhere

If you think it is easy to procrastinate on a school assignment, try killing yourself some time.

As Clayton nears the day of his death in the final chapter, the prose descends into stream-of-consciousness. He ponders the meaning of life and mourns for the life he has lost. He is lingering in that liminal space between life and death, going through the motions.

Finally, on Feb. 24th, he plunges his knife into the stomach of his corpse body:

Fuck I did it.

After days of procrastination and hesitation, the actual experience turns out to be... underwhelming. (It helps that he can’t feel any pain down there.)

I look at the wound, a big, gaping stab hole in my stomach, and it doesn’t really bother me in the least. This was not what I expected everyone. Maybe think of me when the time for you to die is coming and be reassured because it’s not so bad at all. In fact, it’s not bad at all. [...]

I suppose my advice for the living might just be: Live! And when it is time to die, die! [...]

I’m going to go now, done writing. Goodbye everyone.

When I finished the last line, I shut down my computer, took a moment to stare off into space...

...And went for a very long walk.