Your Book Review: The Educated Mind

Finalist #9 in the Book Review Contest

[This is one of the finalists in the 2023 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

“The promise of a new educational theory”, writes Kieran Egan, “has the magnetism of a newspaper headline like ‘Small Earthquake in Chile: Few Hurt’”.

But — could a new kind of school make the world rational?

I discovered the work of Kieran Egan in a dreary academic library. The book I happened to find — Getting it Wrong from the Beginning — was an evisceration of progressive schools. As I worked at one at the time, I got a kick out of this.

To be sure, broadsides against progressivist education aren’t exactly hard to come by. But Egan’s account went to the root, deeper than any critique I had found. Better yet, as I read more, I discovered he was against traditionalist education, too — and that he had constructed a new paradigm that incorporated the best of both.

This was important to me because I was a teacher, and had at that point in my life begun to despair that all the flashy exciting educational theories I was studying were just superficial, all show and no go. I was stuck in a cycle: I’d discover some new educational theory, devour a few books about it, and fall head over heels for it — only to eventually get around to spending some time at a school and talk to some teachers and realize holy crap this does exactly one thing well and everything else horribly.

If my life were a movie, these years would be the rom-com montage where the heroine goes on twenty terrible first dates.

I got to look at some approaches in even more detail by teaching or tutoring in schools. Each approach promised to elevate their students’ ability to reason and live well in the world, but the adults I saw coming out of their programs seemed not terribly different from people who didn’t.

They seemed just about as likely to become climate deniers or climate doomers as the average normie, just as likely to become staunch anti-vaxxers or covid isolationists. They seemed just as likely to be sucked up by the latest moral panics. The strength of their convictions seemed untethered to the strength of the evidence, and they seemed blind to the potential disasters that their convictions, if enacted, might cause.

They seemed just about as rational as the average person of their community — which was to say, quite irrational!

Egan’s approach seemed different.

I began to systematically experiment with it — using it to teach science, math, history, world religions, philosophy, to students from elementary school to college. I was astounded by how easy it made it for me to communicate the most important ideas to kids of different ability levels. This, I realized, was what I had gotten into teaching for.

The man

Kieran Egan was born in Ireland, raised in England, and got his PhD in America (at Stanford and Cornell). He lived for the next five decades in British Columbia, where he taught at Simon Fraser University.

As a young man, he became a novice at a Franciscan monastery. By the time he died, he was an atheist, but — he would make clear — a Catholic atheist. His output was prodigious — fifteen books on education, one book on building a Zen garden, and, near the end of his life, two books of poetry, and a mystery novel!

He was whimsical and energetic, a Tigger of an educational philosopher. He was devoted to the dream that (as his obituary put it) “schooling could enrich the lives of children, enabling them to reach their full potential”.

He traveled the world, sharing his approach to education. He gained a devoted following of teachers and educational thinkers, and (from an outsider’s vantage point, at least) seemed perpetually on the edge of breaking through to a larger audience, and getting his approach in general practice: he won the Grawmeyer Award — perhaps educational theory’s highest prize. His books were blurbed by some of education’s biggest names (Howard Gardner, Nel Noddings); Michael Pollan even blurbed his Zen gardening book.

He died last year. I think it’s a particularly good moment to take a clear look at his theory.

The book

This is a review of his 1997 book, The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding. It’s his opus, the one book in which he most systematically laid out his paradigm. It’s not an especially easy read — Egan’s theory knits together evolutionary history, anthropology, cultural history, and cognitive psychology, and tells a new big history of humanity to make sense of how education has worked in the past, and how we might make it work now.

But at the root of his paradigm is a novel theory about why schools, as they are now, don’t work.

Part 1: Why don’t schools work?

A school is a hole we fill with money

I got a master’s degree in something like educational theory from a program whose name looked good on paper, and when I was there, one of the things that I could never quite make sense of was my professors’ and fellow students’ rock-solid assumption that schools are basically doing a good job.

Egan disagrees. He opens his book by laying that out:

“Education is one of the greatest consumers of public money in the Western world, and it employs a larger workforce than almost any other social agency.

“The goals of the education system – to enhance the competitiveness of nations and the self-fulfillment of citizens – are supposed to justify the immense investment of money and energy.

“School – that business of sitting at a desk among thirty or so others, being talked at, mostly boringly, and doing exercises, tests, and worksheets, mostly boring, for years and years and years – is the instrument designed to deliver these expensive benefits.

“Despite, or because, the vast expenditures of money and energy, finding anyone inside or outside the education system who is content with its performance is difficult.”

Q: Oh, can it really be that bad?

Imagine a group of 100 American adults, chosen at random. They’ve sat through years of science lessons, so you decide to ask them some basic questions. What will they know?

Bryan Caplan, in his book Against Education, cites surveys of what Americans know about basic scientific concepts. Here’s what they find:

of the hundred adults, 76 know that the center of the Earth is hot (this is good!)

only 54 know that the Earth goes around the Sun

only 50 know that not all radioactivity is man-made

only 29 know that ordinary (as opposed to GMO) tomatoes have genes

Q: Well, those are facts, not understanding — and that’s just looking at American adults in general! Surely good schools are doing a better job educating than that?

Caplan cites a famous study by the educational psychologist Howard Gardner:

“Researchers at Johns Hopkins, M.I.T., and other well-regarded universities have documented that students who receive honor grades in college-level physics courses are frequently unable to solve basic problems and questions encountered in a form slightly different from that on which they have been formally instructed and tested.”

Q: Okay, but schools teach reading, writing, and math… right?

Basic literacy and numeracy: yes. Adult-level: no.

If you gave someone two editorials that clashed over interpreting economic evidence, what percent of American adults could compare the editorials? One U.S. Department of Education study that Caplan cites finds: just 13%.

And while 78% could “calculate the cost of a sandwich and a salad, using prices from a menu”, only 13% could “calculate an employee’s share of health insurance costs for a year, using a table that shows how the employee’s monthly cost varies with income and family size”.

Q: I’m afraid to ask about reasoning abilities.

Caplan quotes from a study that looked into how well college students were at applying academic learning to everyday life. The authors write:

“The results were shocking. Of the several hundred students tested… the overwhelming majority of responses received a score of 0. Fewer than 1% obtained the score of 2 that corresponded to a ‘good scientific response’.”

America isn’t so much of an outlier; numbers across the rest of the world are comparable. The 4.7 trillion-dollar question is why.

The usual suspects

Ask around, and you’ll find people’s mouths overflowing with answers. “Lazy teachers!” cry some; “unaccountable administrators” grumble others. Others blame the idiot bureaucrats who write standards. Some teachers will tell you parents are the problem; others point to the students themselves.

Egan’s not having any of it. He thinks all these players are caught in a bigger, stickier web. Egan’s villain is an idea — but to understand it, we’ll have to zoom out and ask a simple question — what is it, exactly, that we’ve been asking schools to do? What’s the job we’ve been giving them? If we rifle through history, Egan suggests we’ll find three potential answers.

Job 1: Shape kids for society

Before there were schools, there was culture — and culture got individuals to further the goals of the society.

Egan dubs this job “socialization”. A school built on the socialization model will mold students to fit into the roles of society. It will shape their sense of what’s “normal” to fit their locale — and what’s normal in say, a capitalist society will be different from what’s normal in a communist society. It’ll supply students with useful knowledge and life skills. A teacher in a school built on socialization will, first and foremost, be a role model — someone who can exemplify the virtues of their society.

Job 2: Fill kids’ minds with truth

In 387 BC, Plato looked out at his fellow well-socialized, worldly wise citizens of Athens, and yelled “Sheeple!”

Fresh off the death of his mentor Socrates, Plato argued that, however wonderful the benefits of socialization, the adults that it produced were the slaves of convention. So long as people were shaped by socialization, they were doomed to repeat the follies of the past. There was no foundation on which to stand to change society. Plato opened his Academy (the Academy, with a capital ‘A’ — the one that all subsequent academies are named after) to fix that. In his school, people studied subjects like math and astronomy so as to open their minds to the truth.

Egan dubs this job “academics”. A school built on the academic model will help students reflect on reality. It will lift up a child’s sense of what’s good to match the Good, even when this separates them from their fellow citizens. And a teacher in an academic school will, first and foremost, be an expert — someone who can authoritatively say what the Truth is.

Job 3: Cultivate each kid’s uniqueness

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau looked out at his fellow academically-trained European intellectuals, and called them asses loaded with books.

The problem with the academies, Rousseau argued, wasn’t that they hadn’t educated their students, but that they had — and this education had ruined them. They were “crammed with knowledge, but empty of sense” because their schooling had made them strangers to themselves. Rousseau’s solution was to focus on each child individually, to not force our knowledge on them but to help them follow what they’re naturally interested in. The word “natural” is telling here — just as Newton had opened up the science of matter, so we should uncover the science of childhood. We should work hard to understand what a child’s nature is, and plan accordingly.

Egan dubs this job “development”. A school built on the developmental model will invite students into learning. And a teacher in this sort of school will be, first and foremost, a facilitator — someone who can create a supportive learning environment for the child to learn at their own pace.

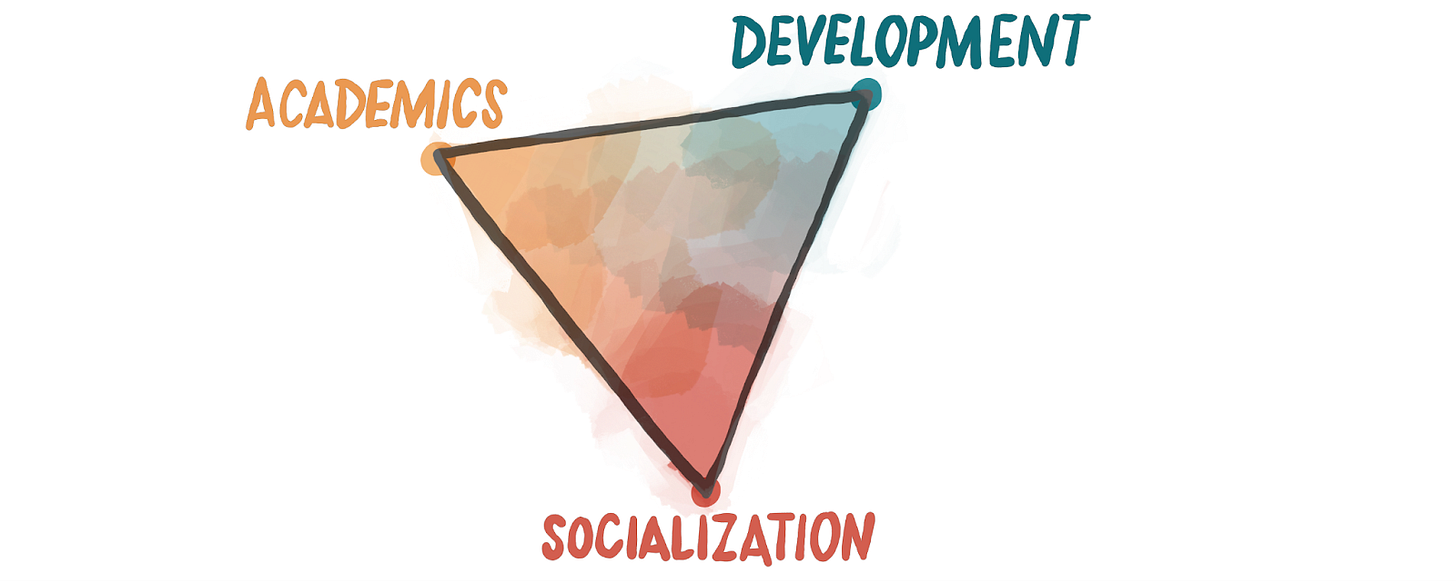

Q: Can you recap those?

We might sum these up by asking what’s at the very center of schooling. For a socializer, the answer is “society”. For an academicist, the answer is “content”. And for a developmentalist, the answer is “the child”.

You want a visual? We might think in terms of these three images:

Kieran Egan laughs at your educational reforms

Okay, of those three jobs, which should we give to schools? You probably have your favorite — I certainly did! But Egan wants you to know they’re all crap. None of them, by themselves, can give us the kinds of schools we want.

Q: I kind of like Rousseau! What’s the problem with pure development?

Like I said before, my bookshelves overflow with authors who want to knock down Rousseau (and the people who followed in his wake — John Dewey in particular). Egan will have none of it: before the developmental approach, many schools were terrible places where children were beaten for getting math problems wrong. “Rousseau and Dewey,” he writes, “have enriched our conception of education in important ways. We will not make educational progress by trying to cut away their contribution”.

But, he continues, there’s no way a purely developmental approach could possibly work! Rousseau imagined human nature to be selfless and kind; this ideal state could only survive if it was kept away from the evils of society — the titular child in his book Emile was kept away from human society, unable even to read, until age twelve.

Of course, schools don’t go this far — they can’t — but I can attest from personal experience that even fairly serious attempts to raise children in an accepting community of peers often crash and burn when faced with actual human nature. Kids reared in the most developmentally appropriate schools can be nasty, bored, and lazy at about the same rate as their mainstream peers.

Q: In my heart, I’m an academicist. What’s the problem with it?

I think Egan was an academicist in his heart, too. His book drips with classical references — so much so that it can make some sections difficult to read. But, he points out, those purely-academic schools really were hellscapes. And their brutality wasn’t something that was just tacked on, it flowed from their understanding of knowledge: enlightenment will come when the right information enters a child’s head, regardless of how it gets in there (or whether the child wants it in there).

And again, Egan feels obliged to point out that we’ve tried this approach for thousands of years, and it hasn’t worked. In fact, Plato’s original vision so obviously doesn’t work that people hawking academic schools have modified their pitch: no longer is the goal for students to understand the Truth, but to cultivate inquiring, skeptical minds who are perpetually dissatisfied with old answers. Can we imagine taxpayers paying for this?

Q: Fine, fine. I’m not a fan of socialization, but I’ll ask the question — what’s wrong with it?

The funny thing is that of the three, this is the only one that has shown its ability to work for a long stretch of time! (As John Calvin pointed out, as animals, we’re pretty pathetic. Socialization allowed our ancestors to become something more than individuals so that they could survive; we owe this job our gratitude.

That said, it would be impossible for schooling today to seek only to socialize. That would require that members of a society share values, and fundamentally agree that their society is good. It also requires that a society not be changing, so the values and skills that are taught to children today will be the ones that will be useful to them in thirty years. Obviously, modern Western society is none of those things. Pure socialization might work for the Amish, or for Catholic trad communities, but not for us. And, frankly, we should feel okay about this. (Do you know where you could get a pure socialization education in the 20th century West, Egan asks? The Hitler Youth!) There really are good reasons to be wary of any education that decrees that its society is uniformly good.

Which combination is best?

Okay, you say, it’s clear that none of these jobs is good on its own — the solution (obviously!) is to smoosh them together. If we do that wisely, the good parts of each will make up for the deficiencies of the others.

This sounds eminently reasonable — but Egan would like to have a word with you.

Q: What’s the problem in combining socialization with academics?

Wouldn’t this be a beautiful combination? Socialization would cohere the school together, and then they could leverage those good feelings to, say, read Aristotle. I’ve seen this work in schools (like conservative Christian academies) founded on a set of specific beliefs. But when intellectual diversity enters in, it becomes harder.

You, perhaps, say that socialization could unite people around their differences — schools could support a society made up entirely of critics! Yes, a society of critics would be interesting, and so would a herd of cats: neither works in practice. Imagine students reading their Ibram X. Kendi books in the morning, then pledging allegiance to the American flag after lunch.

Q: What’s the problem in combining academics with development?

Again, this seems like a beautiful vision: we can invite children into discovering the big ideas. Alas, it crashes into the reef of reality quite quickly: what do we do when kids don’t want to learn about the big ideas? This combination works wonderfully for kids who naturally want to be academics, but — and this is a crucial point that geeky education types too often sweep under the rug — lots of kids don’t naturally want to be academics.

Okay, you say, ignore the “liberatory” element of the developmentalist program, and focus on the “uncovering the nature of the individual child” part: academics can tell us what the students should be learning, and development can tell us how they should learn it. Egan has a thought experiment for you.

Imagine that you get the funding to fully pursue this combined goal — you set up a hundred different types of schools in the nearest big city. There’s a specific school for every possible permutation of learner — a school for big-picture kinesthetic learners who score as INFJ on the Myers–Briggs, a school for detail-oriented auditory learners who score ENFP, a school for marine-biology-loving hyperactive learners who lost their personality test results… you get the idea.

You build the schools, you work out the bus schedule, and then, on the first day, all the students learn exactly the same content.

Because that’s what it means for a school to be an academy — it teaches “the best that’s been thought or said”.

Q: What’s the problem in combining development with socialization?

What’s wrong with telling kids to become their authentic selves, even as you squeeze them into the roles most beneficial to society?

Imagine two rural schools merging together, due to declining local population. Now imagine that one of them is a hippie free school, and the other is a military academy. (That’s a reality TV show I’d watch.)

It’s possible, I suppose, to imagine this working for kids who naturally want to be, say, plumbers, or paleontologists, or presidents — and who happen to go to a school that prepares its students to fill that one role. But the odds of matching students to schools just perfectly seems small.

But enough thought experiments — we can state this in a visual form: behold, the SAD triangle. It’s bright around the edges, but muddled where they mix:

One of the things I love about Egan is that he looks at educational ideas historically. (Most histories of education start around the turn of the 20th century; I remember being excited when I found one that began in the 1600s. Egan begins in prehistory.) And what we’re reminded of, when we see these historically, is that these jobs were meant to supplant each other. Put together, they sabotage each other.

What are we asking of schools?

Of the three possible jobs, which are we asking mainstream schools to perform? Egan answers: all three.

To confirm this, stretch your memory back to your student days, and see if you can put some of the most basic elements in any of these three categories. We’re so immersed in these that they seem obvious, “natural” aspects of schooling, but of course they’re nothing of the sort.

Did you spend your time with other children of the same age? Was your work graded according to a standard? Were you forced to play team sports, or to pledge your allegiance to your nation-state?

All of these, Egan says, bear the fingerprints of the goal of socialization. Progressive reformers in in the 1960s saw these as the markings of a dark conspiracy, but socialization has more warm-feely aspects: counselors to help students cope with the strains of modern society, field trips to the local fire station and historical monuments, and everything “practical” — life skills, sex ed, emotional regulation, and so on.

Did you learn anything that wasn’t obviously useful? Did you read Hamlet, say, or master the Pythagorean theorem, or learn that the planets orbit the Sun (and not the other way around)? That’s the fingerprints of the academic goal.

Finally, did you hear teachers show concern about “age-appropriate” content, or see signs that your school valued individualized learning? Does it seem right to you that learning should be “active” rather than “passive”, or that it’s better for someone to discover something than to be told it?

Did your kindergarten have tiny, child-sized chairs?

All these, Egan says, are the fruit of developmentalism.

The first time I read the book, I wondered at all this. What Egan was saying was indeed lining up with my memories. But perhaps, I thought, he was playing loose with the categories; I was still skeptical that schools really were trying to balance all three goals.

So I decided to check his idea from a different perspective and look up the mission statements of school districts I was familiar with. Here’s the one from the town I currently live in:

“Skills” and “become involved members of a global community” seem to connote socialization, “challenge” and “knowledge” seem to connote academics, and “empower” and “reach their full potential” seem to connote development.

But I wasn’t sure if I was just seeing faces in clouds, so I looked up the mission statement for my hometown:

“Succeeding” seems like socialization, “learning” seems like a nod to academics, and “growing” seems like code for development. But again, I was worried that I engaging in motivated reasoning, so I looked up the largest district I’ve lived in, a city of about a million people:

Wow. That seems pretty clear.

So, to sum up: Egan says that there are three potential jobs we can give to schools. Alone, each of these jobs is terrible; together, they’re worse. And what we’ve done is given schools all three jobs.

A sad triangle, indeed.

What about alternative schools?

I was curious to see whether this “sad triangle” could help us understand other philosophies of education, and why they work (or don’t). Where would, say, unschooling, and classical education, and vocational ed, and Montessori go?

The first three seem obvious. Radical unschooling is in the upper-right, classical schools (with its focus on feeding kids “the best that’s been thought or said”) is in the upper-left, and vocational ed is in the bottom corner.

What can that tell us? Intriguingly, each of those approaches can claim to have done some impressive stuff. I’ve worked with radical unschoolers, and while their skills have often been lopsided (not learning math is an acknowledged issue in the community), they’ve all at least exhibited a zeal for learning the topics they’ve been interested in. (Video games, frequently.)

And I remember a massive study in the early 2000s that asked which kinds of schools actually improved student test scores controlling for the effects of socioeconomics. What it found was that only two types of schools stood out: Catholic schools that were operated by a religious order (e.g. the Jesuits — not local parish schools), and vocational schools.

Q: Oh, that’s terrible evidence. One of those was just personal anecdotes! And what about selection effects? And what about…?

I wouldn’t disagree — and, as Freddie deBoer points out, most educational research is bunk. I’ll take this to be only weak confirmation of Egan’s theory that combining jobs undercuts education.

Are we hosed?

If Egan’s critique is correct, we’re in a bad situation. Educational radicals yell from their dark corners to abandon the middle and come join them; a century of educational reforms have amounted to little more than wobbling around, first in one direction, then another.

At the moment, the conversation about schools in the United States, at least, seems to have hit an all-time pessimistic blech. Freddie deBoer speaks for a lot of people when he says “Even the most optimistic reading of the research literature suggests that almost nothing moves the needle in academic outcomes. Almost nothing we try works.”

I’m not quite that pessimistic — the word “almost” is doing some work, there. There are some reforms that seem to work at the margin: raising teacher pay, making it easier to become a teacher, reducing air pollution, free school lunches, and more. Actually applying what the science of reading has been telling us for a few decades seems a big one.

And perhaps you have your own pet reform proposal. Sure — add it to the heap! What Egan suggests, though, is that so long as we’re bopping around this triangle of jobs, we won’t be able to get the schools that we want.

The dream

There’s a moment at the end of my favorite Bollywood movie that’s become stuck in my head. The protagonists have made the arduous journey to a beachside rural school. In the sun outside, flocks of children are experimenting with art and playing with inventions; inside, the walls are covered with books and the tables are covered with models. The kids are learning joyously and deeply.

In the real world, such places do exist — they’re just exclusive, pulling their students from among the families who are already the most gifted and curious. They don’t make kids this way; they scoop up the kids who are already this way. But in the movie, we’re supposed to believe these are normal children — normal, except they’ve been transformed by a school.

Egan’s wild idea is that it’s possible to make schools like this. He thought that we didn’t have to wait for the communists to make people equal or for the transhumanists to make people smarter. All he thought it required was giving schools a different job — not socialization or academics or development, but something that brings pieces of them together in a new way. But in order to understand that job, we have to come to a cleaner, bigger, and truer understanding of what “education” is.

The road ahead: a special Q-and-A

Q: This is the proverbial thousand-dollar-bill-lying-on-the-sidewalk: if this is possible, someone should have done it now. Is Egan going to give sufficient evidence for me to believe this?

Maybe! I’ll address this in a special section at the end, after sketching out what his theory looks like.

Q: If his theory is even plausibly true, then why haven’t I heard of Egan before?

His books can be hard to read — he was an intellectual’s intellectual; he had difficulty writing a page without a reference to William Wordsworth, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Claude Levi-Strauss, Richard Rorty, Noam Chomsky, or Steven Pinker.

And his paradigm is wonky and multidimensional; he rejiggers common categories, and tells you everything all at once.

But worst of all, when his paradigm is stated plainly, it sounds stupid.

Q: Oh! What… is his paradigm?

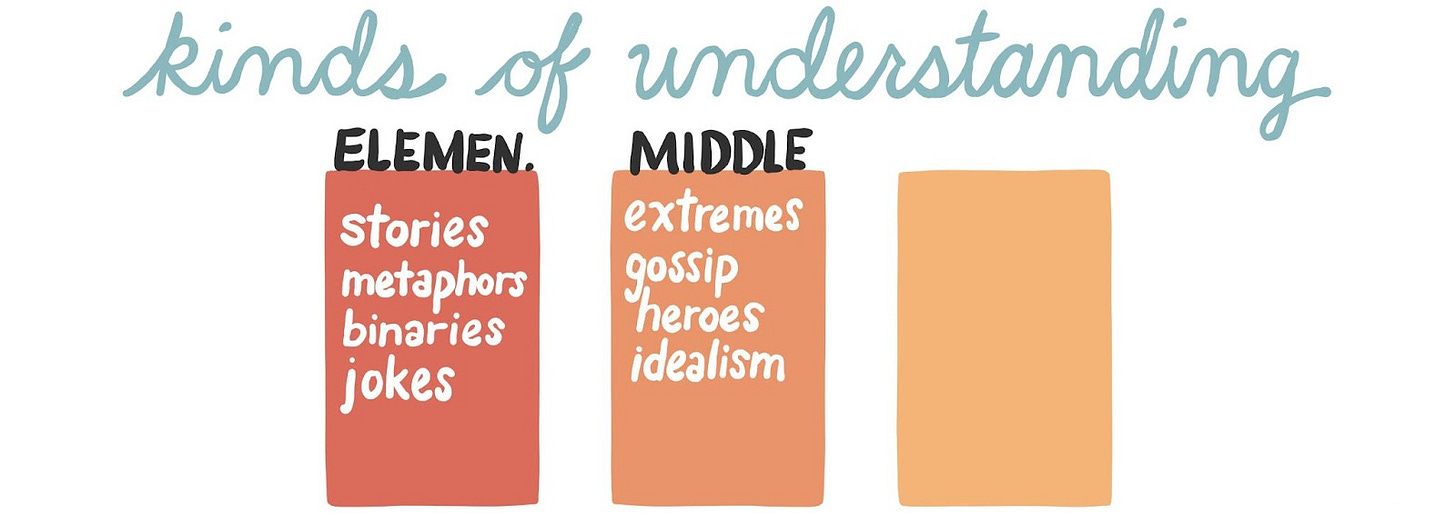

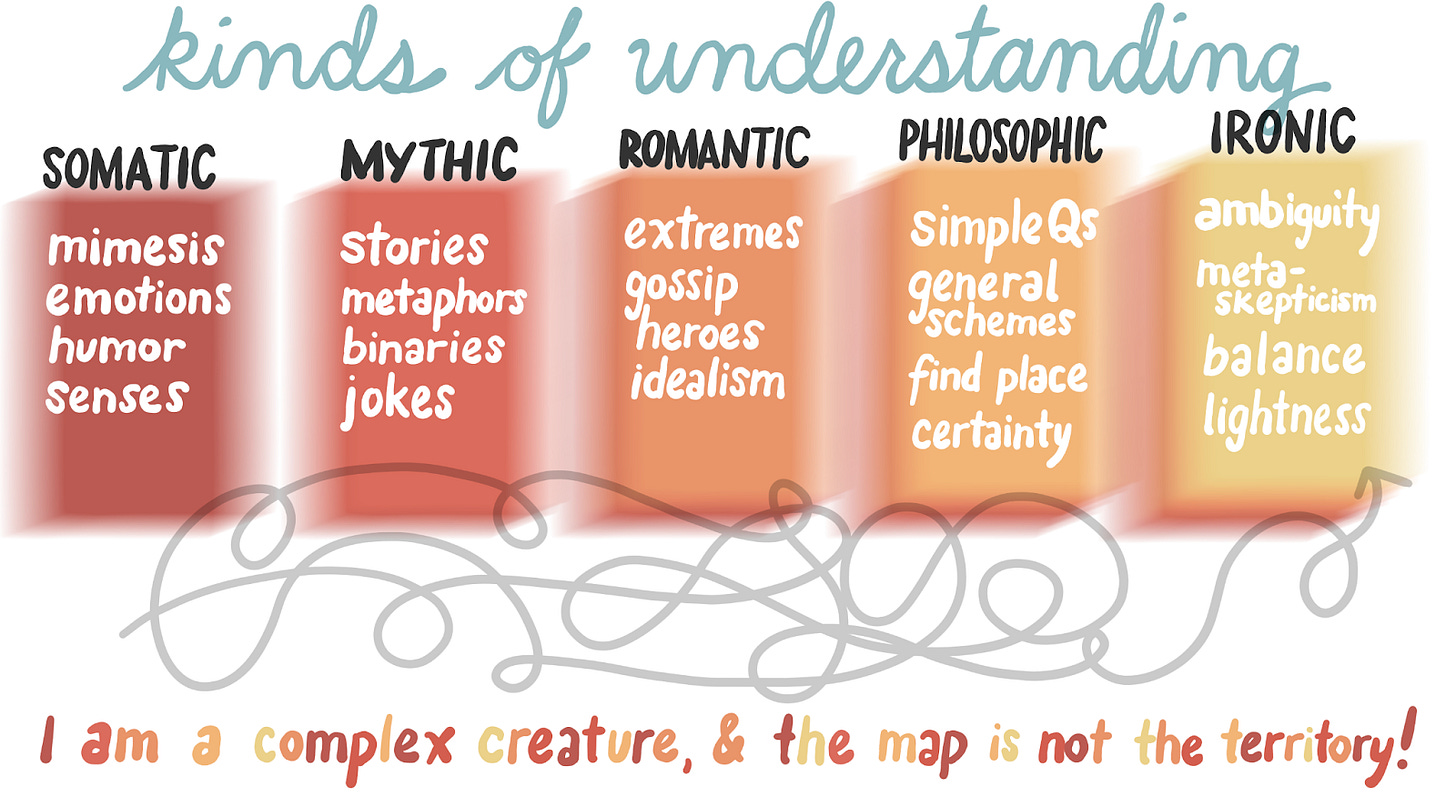

I’m going to jigsaw his book, and hold back his big idea for its own section. First, I’m going to list out some simple observations of students at different ages, and imagine what schooling could look like, if it were built on these principles. (First I’ll do this for elementary school, then middle school, then high school.)

Then I’ll explain how his theory ties all of this together… by clarifying our definition of what education actually is.

Q: I’m not from America; could you be clear on what you mean by those divisions of schooling?

Egan’s framework has three main stages, but they don’t divide neatly into “elementary, middle, and high school”. (The precise age ranges he talks about, if you’re interested, are 2–8, 8–15, and 15 and older.) Regardless, I’m going to use those terms — he sometimes did — because it gives me something specific to imagine. Don’t sweat ‘em.

Part 2: A new kind of elementary school

What’s the matter with elementary schools?

Egan suggests that Plato and Rousseau, for all their differences, might have the same reaction if they visited a modern elementary school: they’d call it “trivial”.

I’ll admit, here, that I have tremendously fond memories of my elementary school years — committed teachers, good friends, and interesting activities. But I suspect my memory has edited out the most typical work I did. Either that, or elementary schools have taken a drastic plunge in quality from the 1980s. My wife and I homeschool now, but before the pandemic, we sent our kids to our local public school, and whenever we volunteered in the classroom, we were horrified. They spent their days practicing reading on shallow texts, or half-mindlessly practicing basic arithmetic. Occasionally they’d bring us home a sign of learning about something from the real world — usually something as intellectually and emotionally compelling as the importance of tooth brushing. And at parent–teacher conferences every year, we’d be sat down on tiny chairs and informed that, while our children were quite bright, they were struggling to pay attention in class. No sh**, I wanted to reply. The school seemed hermetically sealed; almost nothing that felt meaningful from the outside world could get in.

Though they might agree about little else, Egan thinks that Plato and Rousseau would look at the dull worksheets and insipid “hands-on activities” and call modern elementary schools trivial. He agrees, and thinks that fixing this is the first step to building a new kind of school.

Why so trivial?

Ironically, Egan thinks it's all the fault of Plato and Rousseau. Hidden in the ways that both the academicists and developmentalist think about education is an assumption: that children’s reasoning is basically the same as adult reasoning, but lesser.

Q: This isn’t some romantic, children-are-the-real geniuses theory, is it?

Egan actually does think that there’s an intensity to how children perceive the world that we lose — but no, it’s not. He’s building on mainstream cognitive science — just aspects of it that are currently more-or-less ignored in school. The upshot, though, is that he thinks that educational researchers (be they of academic or developmentalist persuasions) see kids as smaller, stupider versions of adults.

Q: But that’s the opposite of what my local developmentalist school says!

It was the opposite of what the developmentalist school that I worked at said, too. But at teacher meetings, I’d frequently hear people ask what was “developmentally appropriate” for a child. I’ll grant that there are perfectly reasonable times to ask this: “Honey, is it developmentally appropriate for our 10-year-old to watch ‘Cocaine Bear’?” is just one of many examples. But “is it developmentally appropriate for our class to learn about world religions?” or “is it developmentally appropriate for our school library to have a book mentioning homosexuality?” probably aren’t some of them. (The latter example was not one that I heard at my progressivist school, but Egan points out that this sort of language is often used by conservative activists.)

This notion of “developmentally appropriate” took on a scientific sheen with the work of Jean Piaget, the famous Swiss psychologist. Before age 12, he “proved”, children aren’t able to form hypotheses, draw conclusions, or think abstractly. This, his followers thought, should transform schools — and so they did! To math, they added in “manipulatives” — physical cubes and rods and such — to help students see math. To the history curriculum, they — well, they ended it. Why waste time, they asked, lecturing students about history that they couldn’t possibly understand? In its place they put the “expanding horizons” model of social studies. One version goes as follows:

In kindergarten, students learn about themselves

In first grade, they learn about their families

In second grade, they learn about their neighborhood

In third grade, they learn about their city

In fourth grade, they learn about their state

In fifth grade, they learn about their nation

In sixth grade they learn about the world

We can admit that there’s an elegance to this model. (I can picture how clever the theorist who first came up with it must have felt!) The downstream effects of it, however, seem horrible. Doesn’t keeping kids ignorant of the rest of the world seem provincial? Doesn’t reinforcing their self-centeredness seem infantilizing? Perhaps we could stomach it if it was founded on some unshakable findings of child psychology — but does it really strike you as likely that kids are incapable of understanding anything that happened long ago or far away? How, Egan asks, can we explain the $50 billion success of a movie franchise aimed at children that literally begins “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away?”

Q: Because… Jedis aren’t history?

The point is, kids obviously have the mental abilities to understand — and in fact care a lot about — things far outside their own experience, and we’ve built elementary schools on a long-dominant model of educational psychology that swears they can’t. This is actually a great example of a general principle. Let’s call it “the Star Wars test”: can our model make sense of the most obvious facts of students? When we find that the answer is “no”, we should at least consider radically revising what we’re doing in school.

What are elementary schoolers good at? (or: kids are smarter than students)

Someone — I can’t now find who — once observed that children seem to lose IQ points the moment they step into a classroom. Egan agrees, and suggests that we think of ourselves as primatologists to kids, Jane Goodalls who investigate children “out in the wild” to see the sorts of things they gravitate to, and do fairly well at.

If we do this, what do we see?

Kids tell jokes, for one. They get mental images stuck in their heads, for another. They engage in role-playing, get lost in reverie, and beat out rhythms when they’re bored. They make ample use of metaphors, tell stories, and insist on seeing the world in terms of abstract binaries (e.g. stupid/smart, cowardice/courage, slavery/freedom, and so on).

These, Egan holds, are the cognitive strengths that children use to understand the world. They’re the things that kids are often about as good at as adults — or much better than. They’re going to be the tools Egan wants us to use to rebuild the entire elementary curriculum, and in fact he spends most of his second chapter geeking out about how we might define these, how they operate in the mind, where they first pop up in history and anthropology, and even how they might have developed in our evolutionary past. I’m going to skip all of that, and get to the curriculum.

From trivial to rich: the trick

What could an intellectually rich elementary school curriculum look like, if we built it on kids’ cognitive strengths? He gives us one suggestion to help us do this: ask where each discipline came from in the first place. What was math before it was math, for example — or science before it was science?

Q: How on Earth could that help?

That’ll become clear later, when we finally uncover what Egan thinks “education” actually is, and see what job he wants us to give schools. For now, take it as a tantalizing hint… or, y’know, just ignore it.

Elementary literature & language

What was literature before it was literature? Before people invented writing, they had rich oral traditions: they told simple stories, recited poems, and shared proverbs. Egan suggests that these bits of oral tradition should form the backbone of the elementary literature curriculum.

Q: What sorts of stories?

As many as we can, and from as many diverse cultures as possible! Folktales are wonderful, as are myths. Think the Aboriginal story of “The Rainbow Serpent”, episodes from the Sumerian “Epic of Gilgamesh”, the Egyptian story of Osiris & Isis, the Greek story of Orpheus & Eurydice, the Chinese Legend of the White Snake, the Japanese Tale of Amaterasu and Susanoo, the Ashanti tales of Anansi, the Aztec myth of Quetzalcoatl, the English legend of King Arthur, the Maori myth of Maui and the Sun, the Roman story of Romulus and Remus, selections from the Indian Mahabharata, the Anglo-Saxon epic of Beowulf, the Inca legend of the Sun and Moon, the Iroquois Myth of the Flying Head (a real thing! look it up!), and the Ojibwe story of Turtle Island.

Q: That was a lot of examples. Are you going to keep giving so many? I’ve got a [mumble mumble mumble] to get to.

Sorry about that. Sometimes, though, I feel that a limitation of reading Educated Mind is that, in trying to keep his book to a manageable size, Egan skimped on examples in some places that it matters. It’s easy to read his occasional example and assume he intends that it hold some central place in the curriculum — when all he wants to do is display how rich and diverse the curriculum could be. (Also: good God, I didn’t even include an example from Norse mythology!) So from now on, just assume that every category could be filled with oodles of examples.

Q: What sorts of poems?

Lots of poems, first of all. We shouldn’t steer toward “fancy” poems — rather, we should find poems that appeal to kids immediately — think Shel Silverstein, Mother Goose, Dr. Seuss, Jack Prelutsky, Edward Lear, or Ogden Nash… that sort of thing. In a biting essay, Egan suggests these poets like these appeal to kids precisely because they leverage kids’ cognitive strengths: “we should find, and encourage saying and singing and shouting aloud verse with strong narrative forms, thumping rhymes and rhythms, the most vivid images, fun with metaphors, and a rollicking story.”

Q: Why proverbs?

Proverbs stick in your mind almost effortlessly. (“All’s fair in love and war!” “When in Rome, do as the Romans do!” “You can’t judge a book by its cover!”) They’re also useful; they capture general truths. Kids can apply them to all sorts of situations, but also discuss them — to what extent are they wise or foolish? (I remember my surprise when I realized that they couldn’t all be true — because you can’t follow “look before you leap” and “he who hesitates is lost” at the same time! I’m embarrassed to say that I think I only realized this when I was in college.)

Elementary science

What was science before it was science? Egan suggests: being immersed in the natural world. We might, he writes, encourage elementary students to “adopt” some feature of the natural world — a patch of grass, a cat, a branch, a stream — and simply observe it at length. To do this, we can use the cognitive strength of reverie.

Q: Oh, do you mean like kids sometimes do in science class nowadays — describe a thing to a partner, make notes, draw it, and label its parts?

No, the exact opposite! That’s all about squeezing the experience into words and forms that we understand. What we want “is less an attempt to know about nature as to know it in some participatory way, to know it as something we are an intimate part of, not set off from”.

Q: That sounds a little… “woo” to me.

It did to me, too… until I remembered my childhood climbing tree. I didn’t much like to go outside as a child, but I had this one tree that I’d climb up and read for hours and hours. If I close my eyes I can bring to mind the precise texture of its bark, the roughness of its broken-off branches, the coolness of its leaves, the always-surprising solidness of its trunk… I’m bigger now, but I think if I were back in my parent’s yard, I could still navigate its limbs with my eyes closed. I have, at this point in my life, read a fair number of books about trees, but I’d be surprised if all of them together more than equaled the amount I learned from that tree — my tree.

Elementary math

What was math before it was math? Egan suggests: counting and logic. We might, then, use rhythms, metaphors, stories, and jokes to help kids become fond of these.

Q: Counting is pretty… basic. Could it really be improved?

Beware of “the curse of knowledge”: Steven Pinker’s phrase for forgetting that something was once difficult! Egan suggests we should spend time helping kids count wonderfully. We can start early with counting rhymes. (“One, two, buckle my shoe! Three, four, out the door! Five, six…”) But we can also help kids use their fingers as metaphors. There are some pretty cool ways of using your hands as an abacus — and did you know that you can count up to 1,023 using just your fingers on both hands, and a knowledge of binary?

Q: Logic — I’m intrigued! Aristotelian, or Boolean?

Neither, for the time being — Piaget was presumably onto something when he found that young children couldn’t reason abstractly, but he was looking at logic in a vacuum. When we put logic into the context of stories, we find that kids can deal with logic just fine. There’s an entire worldwide network of educators, in fact, called Philosophy for Children, who have written whole books about how to do this, and Egan loves it all. Sometimes they read stories and ask simple questions: “What is friendship?” or “What does it mean to be brave?” They also pose ethical questions: “Is it ever right to spill a secret?” And they pose paradoxes: “Can you step in the same river twice?”

Q: You mentioned “jokes” a moment ago. Care to elaborate?

Egan thinks that, to help kids get good at math, you should tell kids jokes.

Q: That’s… new.

I think so, too — but he backs it up pretty well. To be funny, jokes (or at least most kid jokes) rely on a leap in logic:

Why can’t you trust an atom?

They make up everything.Knock-knock.

Who’s there?

Boo.

Boo-hoo?

Don’t cry, it’s just a joke!

To understand the joke, kids have to follow the logic — spotting patterns, making connections, and tracking what their audience expects a word to mean. That’s a lot of cognitive lifting. And Egan goes further, suggesting that we grit our teeth and create methods to help kids invent their own jokes, no matter how horrible they’ll be at first. (The things we do for learning…)

Q: Wait wait wait! What about addition facts, and multiplication tables, and fractions?

Egan emphasizes that his methods are designed to be add-ons to the standard math curriculum. In general, he’s a don’t-blow-up-the-system sort of guy, and if something seems especially weird, you should probably assume it’s an add-on to the regular curriculum rather than a replacement, even if I forget to say so.

Elementary arts

What was art before it was art? Egan suggests we pop our heads into Paleolithic caves for our inspiration. Whatever the specific meaning of all those charcoal elk and aurochs and mammoths (communication with the spirit world? art for art’s sake? a way to impress babes?), Egan thinks it obvious that they were also an attempt to capture an intense experience that would be difficult to express in words alone. What did it feel like to be near an aurochs, or a saber-toothed tiger?

“The arts help us,” Egan writes, “to hear and see afresh, to force our perceptions and sensations to experience again the immediacy and vividness of the world”.

If we follow this, then, we don’t want to help kids build “art skills” so they can draw like an adult — rather, we want to help them amass a repository of diverse aesthetic feelings that they’ll want to express. We should provide them with a riot of experiences.

Q: That couldn’t be more opaque. Examples, please!

Egan writes that we should have children learn to whistle, sing, and click their tongue; we should help them emulate the ways a skunk or a hawk or a stick bug might move through a space. We should expose them to scores of different temperatures and materials. In music, we should help them love Beethoven, yes, but also the Beatles; Tchaikovsky, yes, but also Tuvan throat singers, and also John Cage, whale song, and bird song.

Q: That’s a lot of experiences, but what would they be doing?

An interesting aspect of Egan’s view of education is that he doesn’t seem to think we should push kids right to the “doing” phase. He wants to help kids cultivate an affective relationship with the world.

In any case, he writes that as students get more experienced, we should prompt them to move from merely enjoying these experiences to trying to systematically shape similar experiences. And drawing, painting, and playing music could easily be folded into other parts of the curriculum.

Elementary social studies

What was social studies before it was social studies? Well.

Remember how, just a moment ago, I wrote that you could assume that you should probably assume that Kieran isn’t in favor of junking the curriculum as it currently stands? He suggests we very carefully pick up the elementary social studies curriculum, place it into a trash can, and set the whole mess on fire. He isn’t worried about much of importance being lost. (Remember that the “expanding horizons” model is, to him, the original sin of 20th century educational reform, and he repeatedly quotes student surveys showing that “social studies” regularly wins the title of “most boring subject”.)

In its place, he suggests we put history — which, he hints, we should think of as the centerpiece of the elementary curriculum.

So the real question is what was history before it was history? His answer, surprisingly, is myth.

Q: Egan wants us to teach myths as if they were history?

Not at all. What he suggests, though, is that we look at how myths operate as narratives — so we can design an intellectually vivid history curriculum. And myths really are special: each is built on at least one binary (like weak vs. strong, or lies vs. truth, or so on), and uses that to tell the story of the big picture of the world. They’re so powerful that people can understand it, remember it, and love it — even if that thing never happened.

We should take that power, Egan says, and apply it to things that really did happen.

Q: So what history does he think kids should learn in elementary school?

The great struggles of humanity from across the whole. Flippin’. World.

We’re still talking about young children, so these should be done as simple stories. The goal isn’t to make them history PhD’s, so we needn’t even try to put them in any sort of order. Egan suggests that, in first grade, we pick a single binary like “freedom against oppression” and tell kids a welter of stories, again from as many cultures as possible, and as many times in history as possible.

Q: Can you give examples?

Oh, all right — in first grade we can tell kids the stories of the war of the Greek city-states against the Persian empire, and the slave uprising of Spartacus against the Romans. We can tell them about the plight of Jews in medieval Europe, and of the unsuccessful Sepoy Rebellion in India against the British. We can tell the stories of the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions, and about the Chinese Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. We can tell them the story of the escaped slave Harriet Tubman returning to the South to rescue her kinsmen, the story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges facing threats to integrate her elementary school, and the story of how the Mau-Mau uprising led to modern-day Kenya. We can tell the stories of Mexican-American union organizer Cesar Chavez and of Malala Yousafzai surviving an assassination attempt to advocate for female literacy. The world does not lack for stories of oppression and liberation that can capture the attention of a six-year-old.

Q: That’s… huh. What stories might they hear in second and third grade?

Egan gives examples, but I won’t list them here. He suggests we use a similar approach for each, except that we swap out the binary each year. He thinks “the struggle for security against danger” would work well for year two, and “the struggle for knowledge against ignorance” would work well for year three. (That year could have a lot of overlap with the science curriculum.)

Q: Anything else, for history?

Yes — they should get a sense of Big History. They should get some simple stories about the ice age, the Cenozoic, the age of dinosaurs, the Paleozoic, the origins of our solar system, and the Big Bang. (Because if the ancient Norse can tell their story of the beginning of the universe, by gum, we can tell ours, too.)

To sum up

Egan argues that the problem of early schooling is that it’s trivial — and it’s trivial because the dominant theories of educational psychology see children as lesser versions of adults. What else would we teach them, except dumbed-down versions of what adults learn? But children have certain cognitive strengths that schools aren’t making systematic use of. If we rebuild elementary schools on those strengths, we could turn schooling upside down. We could stop seeing the curriculum as a bag of information to impart, and start seeing it as a set of great stories to tell — and invite kids into. Kids could experience (both intellectually and emotionally) the great struggles of humanity and see that they can join in them. Students could experience the story of education as the beginning of a very real adventure.

Egan’s elementary school: some skeptical questions

Q: I’m not sure I’m understanding what you mean by “mental images”. Care to explain?

It’s an interesting fact of human cognition that just a few words can whip up a complex mental experience. Egan doesn’t just mean what we might call “visual imagery” — the ability to hold, say, the image of a bespectacled, spat-wearing duck in your mind without seeing a photograph. He’s also including what psychologists call auditory imagery, olfactory imagery, gustatory imagery, and tactile imagery.

Q: How could all of that be helpful in schools?

Humanity has a built-in VR system, and we’re not using it! Egan invites us to pretend we’re teaching a class about the humble earthworm. We might list off facts — “earthworms are so many centimeters long, move through soil by means of their something-or-other muscles…” but he suggests we can evoke images, say, “of what it would be like to slither and push through the soil, hesitantly exploring in one direction then another, looking for easier passages, contracting and expanding our sequence of muscles segment by segment, and sensing moisture, scents, grubs, or whatever”. Those facts are now felt by the student; the knowledge has become part of them. And just a few words can spark a complex mental experience, one going beyond literal images to include imagined sounds, smells, tastes, and more. These experiences can feel real and stick with us. (That these mental images are so easy to evoke, and so meaningfully felt, feels something like the proverbial hundred dollar bill on the ground.)

Q: How could metaphors be helpful?

It really is interesting that so much of the “constructivist” turn in psychology — that is, the notion that children don’t absorb knowledge, but construct it — has continued to focus on logics-mathematical reasoning, when there’s been mounting evidence for decades that metaphors are more central. It’s not just that we use metaphors to better understand things we already know, we also use them to grasp new knowledge. What’s more, psychologists have devised tests to measure the skill at metaphor-making, and have given them to people of different ages. What they found was that eleven-year-olds make more metaphors (and higher quality metaphors) than do undergraduates — and that four-year-olds have both groups beat. Again, hundred dollar bills on the sidewalk.

Q: Your talk of “binaries” has me worried — binaries like good/evil and male/female are the source of so many of our most pernicious stereotypes! Isn’t the purpose of education to get us beyond stuff like this?

Yes, it is! Education is supposed to complicate our understanding — but that means we’ve gotta start somewhere, and binaries provide us a natural starting place.

As an uncontroversial example, think about temperature. We all begin as babies by perceiving two temperatures — hot and cold. Later, we add on intermediate categories — warm and cool. (Note that the human body is the assumed mid-point to temperature. Binaries often work like this; “big” and “small” mean “bigger or smaller than me”, “nasty” and “kind” mean “nastier or kinder than I am, except when my brother is really asking for it”, and so on.)

A good story (and an Egan-inspired elementary curriculum is, in a sense, nothing but good stories) will go further, and transform the binary. Toy Story is grounded in the binary of abandonment/belonging: at the beginning, the toy cowboy Woody belongs to his owner, and has his affection. Then a rival comes who threatens his belonging. In trying to get back to belonging, Woody is entirely lost — and to save the day, he has to come to a deeper understanding of what belonging means.

Now, all lessons can’t be Pixar movies. But the good stories (especially in literature and history) will challenge and subvert the binaries they begin with.

Q: I see the pattern of Egan drawing from “as many cultures as possible”. Why so many? Is this a political correctness thing?

If it helps to think of it as such, then, sure! I don’t think Egan would have had a problem with that. But his ultimate reason for including so much diversity goes deeper. For Egan, including such world-wide diversity isn’t optional, and the answer to why is bound up in his definition of education. (Keep reading.) His answer also insists that we, whenever possible, also include stories from the Bible and Homeric epics (the Iliad and Odyssey).

Q: Mmm, stories from the Bible aren’t going to fly in my local school!

So be it! Egan doesn’t spend much time obsessing over the practicalities of…

His interest is in describing what an ideal education might look like, if it were possible. Every lesson, every classroom, and every school is necessarily a compromise.

Q: You make a big deal of poems. But isn’t poetry dead?

An interesting contrast can be made to classical education, which also has kids read a lot of poems — they see knowing great poems as one of the marks of an educated person; again, for an academicist, it’s the information that transforms. Egan begs to disagree. Poems are important because they’re a wonderful way to train their cognitive strengths, like rhythm (poems are language fueling by thumping). We want to help kids learn to use this tool better, and a great way to do that is to help them recite poems that they’ve learned by heart.

Q: “Learn by heart” — is that code for “memorize”?!

It is! Egan is actually quite big on memorization — he points out that all the knowledge in the world can do nothing for a person once they’ve forgotten it. He didn’t, however, appreciate the academicist focus on memorizing without understanding (or at least enjoyment).

Q: I’m still worried about the science curriculum, as you’re describing it. Can you allay my fears?

Honestly, while I feel there’s something profoundly right to how Egan is describing early experiences of nature, I feel the same way. Note that there’s more science coming in the social studies curriculum. But if that’s still not enough, one could bring down aspects of the middle school science stage.

Q: Anything else that Egan suggests we do in elementary school literature and language?

He suggests that we help kids learn a second language! This is so obviously true (why do American schools typically wait until kids lose the ability to naturally absorb languages to start teaching languages?) he doesn’t belabor it, though.

Q: You had mentioned that Egan’s vision seems more internal-focused. Should we be worried about that?

While I strongly suspect that his curriculum would make kids more creative in any way you’d like to measure it, Egan wasn’t particularly interested in “creativity” — he was more about helping kids find the world interesting.

I get the sense that he thinks kids will do things with minimal prompting once they’re loaded up with complex internal experiences.

Q: I think I’m beginning to understand Egan — is he basically saying “make learning fun”?

“Fun”, applied to education, is a dangerous word. Egan worries about the dangers of an emotionally unserious curriculum producing emotionally stunted adults. That doesn’t mean we need to tell students only “serious” stories — only that we treat the world honestly. “Disney-esque sentimentality is the exact emotional equivalent to intellectual contempt”.

Q: But aren't some of these stories too dark for children who have themselves experienced oppression and disaster?

Egan argues that these stories may be especially helpful to them — they can help them understand their struggles better, and give voice to them.

Q: At the very start of this, you promised us “rationality”… but I’m not seeing rationality here! All this talk of “adventure” almost seems to go the opposite direction. What gives?

Wait for it. But for a hint right now — Egan is fond of citing his fellow educational theorist Jerome Bruner, who claimed “any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development”. Bruner was criticized for that; his critics charged that he was ignoring learning differences and socio-economic realities. Egan thinks he was profoundly right.

Part 3: A new kind of middle school

What’s the matter with middle school?

What was middle school like for you?

In math, I recall a jumble of barely-related topics. In literature, I remember reading great literature — Frankenstein, Romeo and Juliet — only in their dumbed-down summary formats. In social studies, I remember teachers proclaiming on the first day of class that unlike all of our previous history classes, this class wouldn’t be about names and dates… and then going on to memorize names and dates. And in science, I remember being forced to dissect a frog only to discover that frogs are — you guessed it — made of slimy frog parts.

Your mileage may vary, but for a lot of us, middle school feels like getting booted out of the (in retrospect) Eden of elementary school, and like marking time before the serious studying of high school. It feels meaningless. In my favorite of his books, Egan calls so much middle school curricula “human deserts”, noting “we have created a system in which the importance of human emotions for meaning seems barely noticed”.

Why so meaningless?

If our dominant approaches to educational psychology fundamentally misinterpret younger children, Egan suggests, they basically throw up their hands when faced with pre-teens and teenagers. Mainstream schools begin to introduce vocational training to help lighten the load, and Maria Montessori famously suggests that adolescents should be sent to go run a farm. Egan is sympathetic to those responses, but points out that they don’t do much to lighten the load that the academic curriculum often becomes at this age.

This feeling of meaninglessness, he argues, is utterly tragic — it comes just when a hunger for meaning blossoms in adolescents! We can see that hunger for meaning in their lives outside the classroom, where their interests ramp up into veritable obsessions.

What are adolescents obsessed with?

What might we see, if we become Jane Goodalls of early adolescence?

First, teens are obsessed with gossip. The motivations of others — why did he do that? and what was he THINKING? — are hypothesized and talked to death.

Second, that they’re pulled toward idealism. Many feel a dissatisfaction with the world as it is, and feel a romantic urge to make it a better place. They’re often lured into simplistic beliefs that promise to help them do that.

Third, they love extremes: they want to find limits, and test them. Obviously, this can show up as risky behavior, but we can also see it in their love for the bizarre — note adolescents’ fascination in things like aliens, cryptids, and ghosts. (Egan loves pointing out that The Guinness Book of World Records is a perennial bestseller among kids at this age. How else would they find out who had the world’s longest fingernails?)

Fourth, they gravitate toward heroes — people who push the edges of those limits. By celebrating heroes, they can vicariously share in their transcendence. Look for the posts hanging up in a teenager’s bedroom to guess what boundaries they feel most hemmed in by: athletes push against physical limits; a death metal guitarist might push against authority and conventional morality. An activist or entrepreneur might push against our dulled morality or our sense of what’s possible.

Finally, we might spot teens taking up hobbies and making collections. Hobbies can be a way to identify yourself as part of a group against the rest of the world (“I’m the sort of person who goes bird-watching!”), and collections can be a way to climb the status ladder inside the community. Egan points out that a collection can also be a way to feel like you have control over what you’re discovering is a very big and complex world of detailed information (“I’ve spotted every one of the fifty most common birds of Texas — even the black-capped vireo!”)

Egan’s insight is that these obsessions give teenagers a sense of meaning, and that we can use them as tools to make middle schools that overflow with meaning.

From meaningless to meaning-soaked

Again, Egan sketches out a new kind of curriculum subject-by-subject. Before, his trick was to ask where the subject first evolved out of; now, it’s to ask who first discovered or created the specific content we’re teaching. “All knowledge”, he writes, “is human knowledge. Everything we know is knowable through the lives of its inventors, discoverers, or users, and we can have access to that knowledge through the hopes, fears, or intentions that drove them”.

Middle school math

Who first discovered the concepts students learn in math? The answer, of course, is a wide diversity of curious men and women living across the world over the last few thousand years. Egan says: bring those people into how we teach math.

If we used gossip and heroes to help students find it meaningful, what kind of math would result? When we teach the Pythagorean theorem, we should give a sense of who Pythagoras was — a cult-founder who worshiped numbers to find God, whose followers (according to a piece of ancient gossip) murdered one of their members who discovered irrational numbers!

Q: Well, sure, that works for Pythagoras, but he’s a known nut job; surely most math doesn’t come from such interesting roots?

When we teach the Cartesian coordinate system, students should meet Rene Descartes, the Calvinist French polymath who saw the possibility that math could decipher the world, if only we could unite algebra and geometry… and invented the xy-plane to do exactly that. When we teach scientific notation, we should call our students’ attention to the importance of the number zero, and tell them the story of the Pope who tried to introduce Arabic numerals to Christian Europe and may have been assassinated because of it. When we teach algebra, we should ask students why “algebra” is Arabic for “the fixing of bones”, and tell the story of what Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi was up to.

We could do this all day. Literally everything students learn in school was first invented or discovered by some interesting person who was struggling to accomplish something hard. To learn is to connect with those people, whether we know it or not. Egan says: help kids know it. Math has been dehumanized: re-humanize it.

Q: So the math curriculum needs to become a history of math curriculum, and math teachers need to become history teachers?

No, the content needn’t change. But with surprisingly little work, we can bring in the gossipy stories of heroes, and their obsessions can spread to students.

Middle school science

Who first discovered the things students learn about in science?

If you’re thinking “scientists”, you’re only partially right. Most of the big-picture ideas that we now think of as “science” were discovered before the word “scientist” was invented, or the discipline was professionalized. Frequently, they were hatched by true amateurs, working in their free time, hungry to unlock the secrets of nature. We can use gossip and heroes to spread their obsessions to students just as we taught math, but Egan points out two twists.

The first is that the content itself can take on heroic qualities: everything is impressive, when you look at it in a certain light. In an interview, Egan once said:

“My book is an attempt to show that, indeed, everything in the world is wonderful, but that schools are designed almost to disguise this slightly shameful fact. We represent the world to children as mostly known and rather dull. The opposite is the case: we are surrounded by mystery, and what we know is fascinating”.

What would even the most boring subjects look like, if we emphasized their heroic qualities? Well:

What’s a tooth? Bone, wrapped in rock, surrounding tiny cells that your body feeds with blood.

What’s a bar of chocolate? A crystal of jellyfish-shaped fat molecules stacked together; when you put it in your mouth you shake them apart into a writhing confusion.

What’s the air around you? The bottom of a 10-mile-deep ocean; when you put your tongue over a soda straw and your Pepsi stops leaking out, it’s not because a “vacuum” is “sucking” it up, but because that ocean is squeezing it into your face.

Again, we could do this all day! And in middle school science, we can. Everything in the world is wonderful; we can help students see this again and again.

The second twist is that science is a subject rich in extremes. Here Egan introduces a concept that we’ll see crop up again: “15-minute segments”. To help us fit as much wonder as possible into a school day, he suggests we supplement the usual school subjects with a few quick lessons. To infuse science with extremes, he suggests we add on three: “human & natural records”, “extremes of animals & plants”, and “cosmology”.

Middle school history

Who first made the things students learn about in history? Why, the historical characters themselves! Since we’ve given kids a grounding in history in elementary school, now we can build on that, going through many of the same events as before, but in more depth, and more vividly.

We’ll leverage the interest with other people’s inner lives to tell stories focusing on the perspectives of the people who made history — zooming in, when possible, on scandalous details. We’ll leverage the tool of idealism to choose historical characters who chafed against their surroundings, and understand what they were trying to accomplish. What was their vision of the world? What did they hope for, and what did they fear?

Q: Isn’t the “great man” approach to history out of fashion?

Egan’s approach doesn’t say that “great men” made history — it’s just leveraging gossip to help kids see history as something meaningful that can expand their own possibilities. “Early adolescence is commonly a time of intense and vivid emotional life, and also a time of deepest boredom and depression… [We] can give shape to the intermediate curriculum and offer the students a world that is rich, complex, varied, and as intense and vivid as their own emotional lives”.

We also should add on another “15-minute segment” just to pump in as many biographies as possible, and from people who don’t always fit into the normal history curriculum. Call it “Brief Lives”, and throw in anyone who’s struggled to push some limit — Mary Wollstonecraft, Jesse Owen, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of the students’ great-aunts, whoever.

As students get older, this can transition to “People and Their Ideas”. Here, we’d focus less on the details of the person’s life, and use it as a backdrop to showing how meaningful some of history’s most important ideas could be. Think Aristotle and syllogisms, Edward Said and orientalism, Confucius and propriety, Cornel West and race, Buddha on the four noble truths, Muhammad and the five pillars, Karl Marx and communism, Adam Smith and the invisible hand, Thomas Hobbes and the state of nature, John Locke and natural rights, Jeremy Bentham and utilitarianism, Thomas Aquinas on the sacraments, Martin Luther on faith, Voltaire on the freedom of speech… you get the idea.

Q: Can you really get a profound understanding of utilitarianism in 15 minutes?

Yes! The point of this segment isn’t to develop a systematic understanding of any one idea, it’s to introduce students to the exciting possibilities of human thought. (As a bonus, this might make them less likely to fall for the first ideology that they encounter later in life.)

Diversity is important for this — as it is with culture. Throughout this, we should also be trying to expose students to as much cultural diversity as possible, because in high school, we’ll be trying to make sense of our society, and it’s impossible to do that unless we have something to compare it against.

Middle school literature & language

You might think that this subject would be easy — that middle school literature is already filled with “strong and clear narratives”, that it deals with “transcendent human qualities such as courage, love, and persistence”, that it focuses on “extremes of human experience”, that it examines “something strange and exotic”.

You’d be right! Egan’s pretty happy with a bog-standard middle school literature curriculum, done well. In this part of the book, his spends most of his limited space suggesting three rather odd activities which could also be useful — especially for increasing students’ awareness of language, so they can use it better.

The first is etymology — not, however, memorizing lists of roots, but in being told the entertaining backstories of specific words. Take the word “berserk”, for example — we now use it to mean something relatively mild (“if my mom catches me coming home late, she’ll go berserk”), but it comes from an old Norse word meaning “a raging warrior of superhuman strength”. And that’s because ber meant “bear” and serk meant “shirt”: soldiers of the bear cult would don the skin of a bear to, in their minds, transform into one — howling, foaming at the mouth, and gnawing the rims of their shields.

(Most adults walk through life with little understanding that the words falling out of their mouths are entities, with their own back-stories. Communication is, at the very least, more interesting when we become aware of this.)

The second is to add on another language to learn — not, this time, to become fluent in it, but just to become aware of how very different human languages can be. (For native English speakers, Sanskrit might work well, or Cantonese, or perhaps even ancient Egyptian. Again, the point isn’t for this language to be useful — it’s to explore diversity.)

The final one is to study humor — not just jokes anymore, but comedy at its finest. Egan cites (at length!) Monty Python as a group of people who were particularly brilliant in their use of the English language. Examining their skits can lead us into not just an appreciation of semantics (the study of how meaning is made from smaller pieces, like etymology) but also pragmatics (the study of how meaning is made in social situations).

Pretty heady stuff, for a conversation about a dead parrot.

Part 4: A new kind of high school

I’ll confess — I loved parts of high school… and among nerdy folks, I suspect I’m not alone. For some of us, this was a golden time. Even at my local public high school, I had access to academically thrilling classes — especially, in my last two years, advanced literature and history. I felt like I was finally understanding the ideas that mattered.

In any case, Egan is quick to acknowledge that, at this level, the sort of education he advocates really is being practiced in some places. What he can add is an understanding of what makes it wonderful, how to make it even more wonderful, and how to make it wonderful for many, many more people.

What’s the matter with high school?

Far too often, even when high school classes are intellectual, they’re dry. For the majority of students, all this academic stuff is experienced as utterly lifeless, a mass of dead information to be squeezed inside one’s head for a test and then left to evaporate. Egan mocks the curriculum wars that seem to be a permanent feature of the teaching life; quoting the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, he says “while the academic left and right bicker over whether the curriculum is too traditional or too radical, they fail to recognize that most students absorb so little of academic culture that the bickering is largely irrelevant”.

Why so dry?

Egan suggests three reasons to explain this.

First, because high school academic classes are too often masses of small details with no sign of the big picture. Second, because they’re typically slavishly disciplinary, and aren’t able to address the questions that span the disciplines. Third, because they’re often designed to bring students through what everyone is sure of, and hide away any controversies. In all of these, Egan suggests that what’s called “academics” in high school is too often a dim imitation of what real academics are actually practicing.

There’s a fourth reason, though, and it’s probably the biggest of all — by the time they get to high school, most students haven’t actually learned that much! An academic approach is designed to connect small details into the big picture; for people who arrive in high school (and college) classes without having already collected much in their heads, academics are going to taste dry.

(An implication of this for anyone trying to improve schools is that we might not want to start with high schools. If your goal is to create a new kind of academic learning, first start at elementary school — or barring that, middle school.)

What motivates mad scientists?

When we wanted to re-conceive the elementary and middle school curriculums, we looked at what students were already good at — kids’ cognitive strengths and adolescents’ obsessions. For this level it might be easier to look — for reasons that will become clear when we finally unveil Egan’s crazy-sounding definition of education — at the sorts of things that bring intellectuals joy.

Q: Which intellectuals?

Take your pick. Galileo, Einstein, Smith, Marx, Goodall, Chomsky, Curie… all the people who took to the life of the mind like fish to water. But that’s a lot to hold in my mind at once, so I’m just going to think about Doc Brown from Back to the Future:

He was high on intellectualism

I’ve never been there, but the brochure looks nice

Let’s call these people “mad scientists”. And let’s pretend we once again took up our job of being primatologists, and snooped on these folks “in the wild” (“in the lab”? this is beginning to get recursive…)… what would we find motivating them?

Asking simple questions, for one. (What is space? What is society? What is a human? What is language?) Building general schemes (big theories) that hold lots of evidence together. Finding their place in the cosmos. And (perhaps above all) seeking certainty.

Once again, Egan suggests we use these as tools to remake the curriculum.

From dry to daring

What could a high school curriculum look like, if it were rebuilt on these tools? Once again, Egan has a trick. This time, it’s to ask what fights have driven the development of each of these fields forward — and how we can help students enter them.

First, a mini-segment!

Intellectuals invented the academic disciplines to better pursue the life of the mind, but the disciplines can get in the way. Some of the most important intellectual discoveries that could help students are too big to fit into any of the disciplines. We need a place to introduce them plainly. Egan proposes another mini-segment — again, just 15 minutes a day, a few times a week — called “Metaknowledge”.

Q: Isn’t that already in the International Baccalaureate program?

Yes, he acknowledges that he’s borrowing from that! This segment would introduce ideas that would enrich student thinking across the disciplines: game theory, cognitive biases, systems thinking, Bayesian reasoning, epistemology, ethics, logic, cultural evolution, and so on.

High school literature

How can we help students enter the big fights of literature? Intellectuals of a literary bent — professors, critics, poets, novelists — delight in arguing over literature like rabbis arguing over the Talmud. Take, just for one example, the debates over Shakespeare’s character of Ophelia. Does she love Hamlet, or is she a victim of his emotional abuse? Is she truly insane, or is she acting? Is she passive, or is she pulling the strings? Oceans of ink have been spilled arguing over questions like these; our students can, perhaps, spill a few ounces more.