Your Book Review: The Collapse Of Complex Societies

Finalist #13 in the Book Review Contest

[This is the thirteenth of many finalists in the book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about two of these a week for several months. When you’ve read all of them, I’ll ask you to vote for your favorite, so remember which ones you liked. If you like reading these reviews, check out point 3 here for a way you can help move the contest forward by reading lots more of them - SA]

Joseph Tainter’s explanation for why complex societies collapse in one sentence: the collapse of a society is a response to declining marginal returns on investment in complexity.

Tainter uses ‘complexity’ pretty loosely. He’s referring to a broad set of things that include agriculture, fuel extraction, scientific research, education, and sociopolitical complexity. He notes that in any area that produces something good for a society, the lowest-hanging fruit is plucked first, and then value gets harder and harder to extract until there’s little room for improvement. States are the biggest manifestation and driver of social complexity (and I’ll talk mostly about states in the rest of the review) but he’s talking about the abstract property of a society – how large it is, how many specialized social roles it has, how many mechanisms for organizing or doing things.

In Tainter’s model, states exist to solve problems. You can think of them as either solving collective social problems, like getting big irrigation systems to work (‘integration theory’), working to placate / oppress the productive populace enough that the elite can keep extracting surplus from them (‘conflict theory’). Either way, states tend to increase in complexity in order to deal with new challenges. That increased complexity imposes greater costs per capita. When the system hits some critical point on the return curve (highest point the graph below), the next stressor makes the state try to unlock the next stage of complexity, which demands more resources than the population can bear. Peasants revolt, republics break away, and the state falls apart.

(Tainter is clear that he doesn’t think collapse is always bad – sometimes it just means that the state falls apart into smaller components that are more the correct size to look after itself.)

At the critical point:

A complex society experiences increased adversity and dissatisfaction. Stress begins to be increasingly perceived, and if modern history is any guide, ideological strife (for example, between growth and no-growth factions) may become noticeable. The system as a whole engages in ‘scanning' behavior, seeking alternatives that might provide a preferable adaptation. This scanning may result in the adoption by segments of the society of a variety of new ideologies and life-styles, many of them of foreign derivation (such as the proliferation of new religions in Imperial Rome). … there may be increased investment in research and development (to the extent that declining resources permit), as solutions to declining productivity are sought, and in education, as individuals position themselves to reap a maximum share of a perceptibly faltering economy. Taxes rise, and inflation becomes noticeable. ... productive units across the economic spectrum increase resistance (passive or active) to the demands of the hierarchy, or overtly attempt to break away. Both the lower ranking strata (the peasant producers of agricultural commodities) and upper ranking strata of wealthy merchants and nobility (who are often called upon to subsidize the costs of complexity) are vulnerable to such temptations.

The visualization I had of his model after reading his book is of a candle being lit and consumed by the flame until there is nowhere for it to go. The length of a wick is determined largely by the environment – how much people the land can support, how many wealthy neighbors there are to trade with or conquer – and the flame will consume it inch by inch in the normal course of things, but faster when there’s some adversity. Where it cannot add complexity to the system to squeeze out the next advance, it collapses.

That seems... weird. I’ll try to make more sense of it after summarizing the book. I’ll start with Tainter’s list of major areas of complexity.

1. Systems of extracting food and fuel

Each advance leading from hunter-gatherers to industrial agriculture has made the food costlier to acquire. The agriculture section is full of graphs that look like this, showing the more work you put in the less yield you get per unit of work:

Similarly, modern systems for extracting coal or oil from the ground are increasingly complicated and expensive:

As the land in the late Middle Ages was increasingly deforested to provide fuel and agricultural space for a growing population, basic heating, cooking, and manufacturing needs could no longer be met by burning wood. A shift to reliance on coal began, gradually and with apparent reluctance. Coal was definitely a fuel source of secondary desirability, being more costly to obtain and distribute than wood, as well as being dirty and polluting. Coal was more restricted in its spatial distribution than wood, so that a whole new, costly distribution system had to be developed. Mining of coal from the ground was more costly than obtaining a quantity of wood equivalent in heating value, and became even more costly as the most accessible reserves of this fuel were depleted. Mines had to be sunk ever deeper, until groundwater flooding became a serious problem. Ultimately the steam engine was developed, and employed to pump water out of mines. A similar historical course was followed with the depletion of the forests in the earliest settled parts of the United States.

...

Modern data not only illustrate the trend quantitatively, but indicate that the process of declining marginal returns is continuing. Adjusted for inflation, each dollar invested in energy production in 1960 yielded approximately 2,250,000 BTUs. By 1970 this had declined to 2,168,000 BTUs, while in 1976 the same dollar could produce only 1,845,000 BTUs.

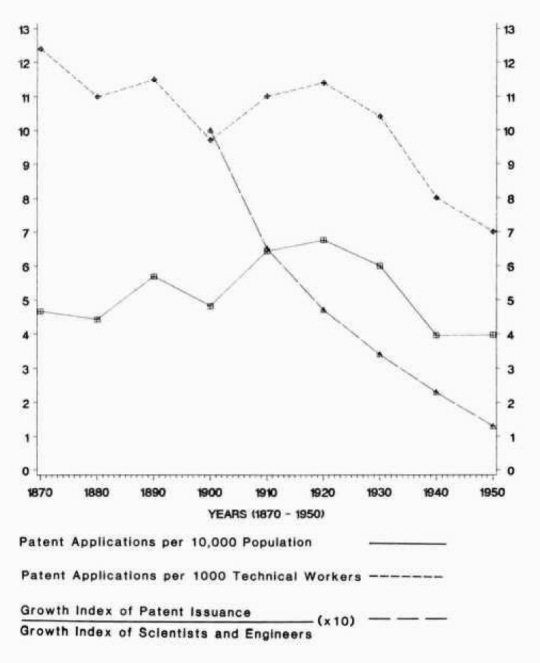

2. Science / invention

Using patents as a proxy for how much scientific innovation is happening in a nation, Tainter shows that the number of patents per scientists declined pretty consistently in the 20th century. The graph covering the biggest time period looks like this (USA):

The trend continues after 1950:

In a survey of 50 countries (many of which do not invest heavily in military R&D), Evenson showed that inventions per scientist and engineer have declined in nearly all cases between the late 1960s and the late 1970s (1984: 89). In both the U.S. and Japan, between 1964 and 1979-80, the ratio of patents to productive inputs fell in almost all industries.

When a field is established, you can get a lot done by making relatively obvious inferences and running cheap tests. (I’m not sure what share of the patents in the above graph were physics-related but it seems notable that 1905 was Einstein’s annus mirabilis, when he published papers on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, and special relativity). After that, you reach the questions you can only resolve by smashing particles into each other in a 10-kilometer long tube, or by buying millions of dollars’ worth of GPUs so you can check how much better neural networks do if you just let them have a billion parameters.

This is obvious, but I don’t think I actually put it fully together until reading this book that science might have slowed down for good. When I was young I read about all the amazing things that had been discovered and accomplished in the 20s – 50s (physics and space exploration), and I came of age during the digital revolution, so it seemed to me that it might just keep going on – something incredible happening every 50 years, civilization unrecognizable at every century to the citizens of its last. But there’s no reason for this to be true! No one so far in history who has said “and now things will stay about the same forever, or at least cycle between dark ages and the level of knowledge and infrastructure we have now” has been right, but at some point that has to be true.

3. Education and job specialization

Similarly, specialized job training and further education has diminishing returns:

The first two years of education, according to Strumilin, raise a Soviet worker's production skills an average of 14.5 percent per year. Yet the third year of education yields an increase of only an additional 8 percent, while the fourth through sixth years raise skills only a further 4-5 percent per year (Tul'chinskii 1967: 51-2). Such examples indicate the kinds of costs incurred by complex societies that must invest resources in preparing people for specialized tasks. While the performance of these tasks may be quite essential to the society's needs, it cannot be claimed that benefits for investment in education increase proportionate to costs. To the contrary, increasingly specialized training serves ever narrower segments of the system, at ever greater cost to the society as a whole.

4. Sociopolitical complexity

Organizational solutions tend to be cumulative. Once developed, complex social features are rarely dropped. Tax rates go up more often than they go down. Information processing needs tend to move in only one direction. Numbers of specialists ordinarily don't decline. Standing armies rarely get smaller. Welfare and legitimizing costs are not likely to drop. An ever increasing stock of monumental architecture requires maintenance. Compensation of elites rarely goes down. What this means is that when there is growth in complexity it tends to be exponential, always increasing by some fraction of an already inflated size.

I think food and fuel is an area where it’s kind of a ‘fact of nature’ that it’s going to be harder and harder to pull gains. Scientific research seems different from all the other arenas that yield societal value in that, once in a while it’ll produce some high-up fruit that you can use to plant a new tree. Human organizations seem different from either, because here you cannot undo investments for social reasons. If a mode of agriculture is too much work you can “just stop” doing the hardest couple tiers. If a branch of research isn’t worth it you can close the lab and society can keep coasting on the products of prior discovery. Not so with human organizations. Theoretically you can decomplexify it in the same way you can just stop doing the more intensive forms of agriculture, but this tends to be intractable.

The emphasis on this distinction is mine, because I think the irrevocability of investment and complexity in human organizations is the primary thing that makes societies collapse, if Tainter’s model is right. But Tainter never makes this distinction – he spreads out key-seeming observations to this effect throughout without pulling it into the limelight, which is maddening. On my reread of the book after a first pass I made a section in my notes titled “on why complexity cannot be taken back” and gathered three excerpts, sprinkled throughout the book:

Parkinson has elsewhere suggested that, beyond a certain point, increasing taxation begins to yield declining marginal returns. Two of the reasons for this are increased avoidance on the part of taxpayers, requiring still further bureaucracy to enforce compliance, and inflation, which reduces the value of the money collected.

and

Among contemporary societies, as regulations are issued and taxes established, lobbyists seek loopholes and regulators strive to close these. There is increased need for specialists to deal with such matters. An unending spiral unfolds of loophole discovery and closure, with complexity and costs continuously increasing (Olson 1982: 69-73).

and

Once this population segment has become accustomed to any pattern of increasing investment in legitimization, continuance of this trajectory is necessary to maintain the compliance status quo. Increased investment in legitimizing activities brings little or no increased compliance, and the marginal return on investment in legitimization correspondingly declines. … The appeasement of urban mobs presents the classic illustration of this principle. Any level of activities undertaken to appease such populations - the bread and circuses syndrome - eventually becomes the expected minimum.

So: there are some reasons sociopolitical complexity is different from the complexity of systems that yield food or science.

(1) There’s a tax/regulation avoidance <-> compliance enforcement chain that only ever moves the taxation arm of the government in the direction of bloat.

(2) People keep wanting the state to do new things for them, and when they get those things, they start taking those for granted and require more benefits from the state to consider it legitimate.

Again, these seem like important observations, and I am indignant at Tainter for not centering them. The major question I felt was insufficiently addressed was: Well, why can’t a state develop its agriculture program and science funding and state infrastructure to the point where it’s getting the most yield it possibly could and stop growing? These points are Tainter’s (underdeveloped) answers to one of those areas.

I’ll note that subunits of society don’t need to be in conflict (as in regulation avoidance/enforcement spirals) for increasing complexity to bring costs up – entities that nominally want the same thing can waste resources on working around each other just fine in a sufficiently large system. This isn’t a great example, but it’s what I have on hand: My housemate’s family lives in Indiana, whose state government showed COVID vaccination sites with individual appointment availability, but not an aggregated list of sites that had slots in the near future. My housemate built a simple scraper that updates a website giving this information. The state caught on after a week and blocked the scraper, which was making a request every two seconds. The Indiana state website could much more easily build the same feature by querying their own database, but they happen to be an organization that isn’t outputting this behavior, so the only people who are doing it are outsiders who annoy them by putting load on their network resources. The coherent extrapolated state of Indiana wants vaccines to go out efficiently, but subunits are wasting time working around each other.

5. Economic productivity

Tainter cites the same kinds of studies that were discussedonSlatestarcodex and Marginal Revolution a few years ago showing that the US economy is taking more and more effort to produce the same goods over time, and gives it much more cursory treatment – handwaving it as being the same kind of phenomenon that drives decreasing returns in the same areas above. I’m not convinced, and think the more recent explanations/discussions linked above are stronger. The first link above is Scott’s compilation of hypotheses generated by commenters on cost disease and I sadly turned into econphobic epistemic jelly reading them. I certainly don’t think Tainter’s treatment is a strong one compared to others in that discussion, which is a shame, because I think his “increasing complexity kills societies” argument is strongest when leaning on the pillars of sociopolitical and economic inefficiency. Whatever is causing increasing costs, though, Tainter considers the kind of thing that causes societies to collapse.

A Tale of Three Societies

After explaining his model of various types of diminishing returns on complexity eventually pushing societies to collapse, Tainter picks three states to apply his model to. He chooses out three civilizations at different levels of complexity – the Chacoan civilization (‘proto-state’), the Mayan civilization (‘definitely a state but not an empire’), and Rome (Rome). In 1988 the Mayan script had not been fully decrypted, and Chacoa didn’t have writing, so Tainter draws primarily on archaeology to put together pieces about what happened there.

For each of these societies, Tainter identifies a strategy they were following, or an area of investment that served them well, and explains how it eventually led to an overtaxed population and the secession of that strategy.

For Rome, that strategy was territorial expansion, which served them well when they were small and had a lot of wealthy neighbors, and badly when they were large and ran out of people to loot:

For a one-time infusion of wealth from each conquered province, Rome had to undertake administrative and military responsibilities that lasted centuries. For Rome, the costs of administering some provinces (such as Spain and Macedonia) exceeded their revenues. And although he was probably exaggerating, Cicero complained in 66 B.C. that, of all Roman conquests, only Asia yielded a surplus. In general, most revenues were raised in the richer lands of the Mediterranean, and spent on the army in the poorer frontier areas such as Britain, the Rhineland, and the Danube.

Eventually, the costs of administration and of placating the urban masses overwhelmed them. The rulers kept depreciating currency, borrowing against the future, to pay its soldiers. Taxes were high, and peasants fled the land. Or they wouldn’t flee the land but aristocrats would lie about how many peasants they had to farm so they wouldn’t be taxed so heavily. Eventually the Western Roman Empire fell to a mass movement of proto-state people it could handle in less strapped times.

Elsewhere in the book Tainter says (not specifically about Rome) that people in conquered territories tend to gain more rights, so they slide from “heavily exploited to serve everyone else in the empire” to “fomenting for benefits, have to be placated by exploiting someone else”, so that’s probably part of his explanation for Rome’s fall:

Given enough time, subject populations often achieve, at least partially, the status of citizens, which entitles them to certain benefits in return for their contributions to the hierarchy, and makes them less suitable for exploitation.

For the Mayans, the strategy that brought them down was investing in a red queen race of population growth and agricultural intensification. There were several major power centers in competition, and they might have prioritized population growth as a matter of policy – when food started becoming scarce, male height started going down while female height didn’t, which some people think indicates that Mayans prioritized keeping women healthy for population growth reasons. (Tainter doesn’t say, but I assume they ruled out the hypothesis that the women were never that well fed to begin with, since it’s easy to check for – male:female height distributions under equal nutrition are well known.)

Mayans practiced similar kinds of agriculture, and hard times hit everyone at the same time. This was a major cause of population clustering around the power centers / states:

Although major fortifications did exist, the majority of conflicts (if they were indeed related to subsistence stress) would have involved raids on fields, as crops neared maturity, and on peasant villages and storage complexes, after the harvest. The insecurity that this created among the rural population selected for nucleation around secure, regional centers.

The people in these power centers spent a lot of effort erecting monuments. One reason to do so was to signal legitimacy of reign – apparently a ruler succeeding more impressive kings would go into a frenzy of building at the start of their reign. And the bigger and more ornately carved with vicious depictions of what the creator society would do to prisoners of war the better. For whatever reason, Mayans didn’t have standing armies, so their main way of signaling “this is how many people we have (and this is how badly we’ll screw you over if you attack us)” was by building monuments:

Mayan sculpture regularly depicts military themes, and rulers are often shown judging, even standing on, captives. At a center displaying such art, emissaries and visiting elites from potentially competitive centers would constantly encounter sculpture and painted surfaces showing the military prowess of their hosts, and the harsh manner in which they treated prisoners. Such visitors could not help but receive the correct message from art, such as the Bonampak murals, showing the torture and execution of prisoners. Although no expert on the subject, my impression is that Mayan art more frequently displays mistreatment of prisoners than, say, Roman Imperial art (e.g., Becatti 1968). Roman prisoners of war (especially notable ones) are often shown in, for example, the victory processions of emperors, but mistreatment of prisoners is not depicted so conspicuously as in Mayan art. The Romans maintained a powerful standing army, and their art does not concentrate on the mistreatment of prisoners. Classic Mayan states did not have standing armies. Their art depicts terrifying treatment of enemies. Without real strength, propaganda was the next best thing.

I’m not sure why the Mayans didn’t have standing armies and find this quite interesting. Perhaps that was common in sufficiently labor-taxed states where everyone had to spend as much time as possible extracting the next head of maize from the soil? The other book I’ve read recently about war and proto-states (War In Human Civilization) indicates standing armies was a very advantageous thing to have, because the common pre-state alternative was calling forward an assembly to deal with every incursion on an ad hoc basis, and such societies tended to get overwhelmed by a persistent, professional force, even if that persistent force was smaller. (Rome was able to beat back numerically superior invasions from proto-states for similar reasons.)

The population, agricultural output, number of administrators, and monumental construction at Mayan centers increased until it hit some critical point. The following graph shows monumental construction (one katun is approximately 20 years):

For the Chacoans, a trading society that arose in ~900AD in Chaco Canyon in present-day New Mexico before dissipating in ~1200, the strategy was adding nodes to their trade network. Trade was highly advantageous for the people in and around Chaco Canyon, because high and low elevation crops were available at complementary times of the year. Tainter thinks the need for coordination spurred political centralization:

If each local group had to allocate resources toward the tasks of identifying potential trading partners, identifying these partners’ yearly production levels, and establishing reciprocal economic relations with each, the duplication of administrative costs by hundreds of local groups would have been enormous. These costs were substantially reduced when the regional population jointly supported a single administration that served the economic needs of all groups.

Each node of trade had a Great House, which ranged from one room to several hundred on multiple stories, used for storage of surplus and housing the elite. The Great Houses of Chaco Canyon traded extensively with neighbors 50~80 kilometers in various directions, building and maintaining hundreds of kilometers of wide roads for trade – the Chaco Canyon nodes are in the little rectangle in the map below.

Over time, the groups in the area became increasingly economically linked. The Canyon Great Houses took 150~200 thousand trees to roof, obtained from dozens of kilometers away. (I assume carried on foot.) The Canyon population exceeded that which the nearby land could feed, and imported food – between 1020 and 1120, one Canyon site imported 111 pottery vessels per day on average from a neighbor 50 miles away, which probably contained maize and other crops.

With insurance against food shortages, population grew, and new nodes with Great Houses were added to the network. By year 1000, Great Houses were 54km apart on average. As more Great Houses were built, the mean distance fell to 31km. At ~1100 the system was at its height; ~70 Great Houses have been identified total, so perhaps that’s how many there were. Adding nodes decreased the average usefulness of trade.

By ~1200, the Chacoan system had collapsed. A drought may have precipitated this; the most agriculturally productive neighbors may have seceded from the network first. The remainder had no military standing to prevent this. No more planned towns, roads, no more construction of Great Houses. Various scholars say that “after 1300A.D., the region was essentially abandoned by agricultural peoples”.

Tainter’s analysis:

This marginal, low productivity environment offered diversity as its best characteristic. The Chacoans initially made wise use of this feature, but came ultimately to dilute its effectiveness. An energy averaging system is most effective when adding a new participating community means increasing the diversity and/or productivity of the regional exchange pool. The Chacoans initially pursued such a strategy. Increasingly, though, communities were added that did not augment the system’s diversity, and that actually caused deterioration in the ratio of communities/diversity.

It’s hard for me to assess how well the model fits these cases, because we know relatively little about Mayan and Chacoan societies, and the Roman collapse is a freight train of facts and contingencies and crises that a casual reader can’t untangle, only get run over by. But my cautious opinion right now is that, much as I enjoy Tainter’s attempt to sketch a unifying principle of societal collapse, it elides too much of the difference between Malthusian collapse that’s brought on by the population outruns agricultural output (where the ‘increasing administrative/elite burden’ thing seems like an epiphenomenon), and everything else (Rome was underpopulated at the time of its collapse). And the everything else part is what’s interesting to me, as a person in the 21st century. Which brings us to his comments on...

Modernity

Tainter thinks that once we entered modernity, rapid collapse – that is, the sudden loss of complexity, as opposed to slow disintegration – became impossible. Rapid collapse, he thinks, is only possible in a power vacuum.

He distinguishes states like the Ottoman and Byzantine empire (which was surrounded by peer polities and gradually lost power and territory to them) from states like the Western Roman Empire, which left a bunch of small splinter states that weren’t immediately assimilated by a rival. The only way states in a competitive network collapse is if they’re at similar points of running out of slack:

Collapse for such clusters of peer polities must be essentially simultaneous, as together they reach the point of economic exhaustion. Since in both cases no outside dominant power (in the Mesoamerican Highlands or the eastern Mediterranean) was both close enough and strong enough to take advantage of this exhaustion, collapse proceeded without external interference and lasted for centuries.

He thinks that collapse in modernity will either be like that – everyone falling apart at once – or not really a collapse, since the failed state will be eaten up by a rival who has energy left for competition.

In fact, there are major differences between the current and the ancient worlds that have important implications for collapse. One of these is that the world today is full. That is to say, it is filled by complex societies; these occupy every sector of the globe, except the most desolate. This is a new factor in human history. Complex societies as a whole are a recent and unusual aspect of human life. The current situation, where all societies are so oddly constituted, is unique. ...

None can dare withdraw from this spiral, without unrealistic diplomatic guarantees, for such would be only an invitation to domination by another. In this sense, although industrial society (especially the United States) is sometimes likened in popular thought to ancient Rome, a closer analogy would be with the Mycenaeans or the Maya. ...

Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole. Competitors who evolve as peers collapse in like manner.

Poor Tainter. He published this the year before the Soviet Union underwent what distinctly looks like ‘rapid collapse’. I think we can cross out “individual nations won’t fracture” as a failed prediction. But I’m puzzled he made it without specifically carving aside an exception for mega-states – he notes multiple times elsewhere that there are territories that are a net loss to conquer because the cost of administration and other complexities outweighs the benefits.

Tainter points at another consequence of everywhere being like competing peer polities: when collapse is not an option, political action of people at the bottom is aimed at reformation rather than decomposition. He points to ‘no realistic expectation of being able to decompose into smaller units of society’ as a correlate/precondition for participatory government.

Why not grow to the optimal point and stop?

Why can states not simply grow to their optimal size and stay there? If becoming more administratively complex would cost more than it would produce, simply do not do that. If conquering a territory would be a resource drain, do not conquer it. Or conquer it to bring in the initial surge of loot, and then when administering it is more than it’s worth, relinquish control. What was stopping Rome from releasing and re-conquering territories every 100 years like a huge field with a big fallow period? Why hang on?

I don’t know why they hung on, but it seems useful to separate revocable vs irrevocable complexity. Having a lot of territory is revocable: you can relinquish it. But what can you not take back? These seem like the key reasons a state can’t simply stop growing:

Sociopolitical complexity is hard to take back because: (1) people start taking for granted the benefits provided by the state, so the state has to keep doing new things to keep legitimacy, and (2) dynamics like tax evasion / closing loopholes + enforcing compliance only ever drive complexity up.

Fossil fuels that are increasingly hard to extract (there is no simpler form of fuel left to consume when you try to decomplexify your system).

Population size is totally revocable, but it seems very hard to revoke or even keep steady in a controlled, non-atrocious way.

Tainter briefly addresses the possibility of a sustainable society that hits the point of zero marginal return on complexity and freezes into place. I wrote my answer above for why this is hard or impossible. This is his:

Why can't a society that has reached some optimum cost/benefit ratio for its investment in complexity simply rest on its accomplishments? While long-term equilibrium may be possible in comparatively simple foraging societies that are demographically flexible, it is less likely in more complex settings of greater density. Hunter-gatherers typically have the option of dispersing under resource shortages, so that population density is lowered in a distressed area. So long as new land is available, agriculturalists often have the same option. Where demographic and/or sociopolitical factors limit the option of dispersal for a large segment of a population, though, the solution to stress must often be greater economic and/or sociopolitical investment. Since all human populations experience recurrent stresses, complex societies must constantly develop organizational features designed to alleviate new problems.

I think this explanation sucks. Considering that “why can’t states just grow to a good size and stop” is one of the obvious questions raised by his book, his weak answer here is, to me, the greatest flaw of the book.

Attempted Model Applications

Non-state applications

I almost think US colleges are a better fit than the nations I’ve lived in for Tainter’s model of states in a peer polity system. Increasing costs? Check. Increasing administrative complexity? Check. More amenities to appease the restive population? Check. I tried to think of whether firms can be thought of the same way, but that’s harder since the ‘citizen’ analogue is split three ways between customers, employees, and shareholders.

Ilive in the USA. Are there any doomed strategies it’s following?

I have too distant a relationship with current events to have informed takes on this, but here are some ideas:

⊙ The USA’s reliance on immigration to supply young people who can keep the economy running seems a little alarming just because it can’t be kept up as the USA’s relative desirability declines, but it doesn’t have declining marginal returns, exactly.

⊙ I’m not sold on Tainter’s idea that the state has to keep increasing benefits to the citizenry to stay legitimate, but the USA has been spending an increasing amount of its budget on healthcare and pensions. (Not sure what this looks like if you adjust for the aging population, but from eyeballing it looks like it’s outpacing the proportion of old people.) The best visualization of this phenomenon is from heritage.org, a conservative think tank:

Which seems pretty similar to the nonpartisan Pew Research Center’s (more visually confusing) presentation of government spending as a proportion of GDP:

⊙ The US national debt is growing. That seems obviously concerning to me, but some people say this is fine. I’m not sure why – it seems just as much borrowing from the future as Rome depreciating its currency, which very much did get it in trouble, according to Tainter. Even the people who agree it’s obviously concerning don’t seem “holy shit this is going to be a big input into the downfall of our civilization” levels of concerned. Not sure what to think about this.

⊙ The first world might be capturing more of the gains through trade when trading with developing countries (e.g. Japan buys peanuts from Sudan at a price that’s much closer to the indifference price of Sudanese sellers than that of Japan’s buyers), a source of ‘income’ I expect will disappear as those developing countries become more powerful. I tried to find out how true this by googling around for it; apparently this idea is a subclaim of ‘dependency theory’ and if you open the Wikipedia article for it, there’s a banner at the top saying “someone wrote a rant here, please trust it less than usual”.

I’d be interested to hear from more informed commenters on how true they think this is. The implication for the societies in developed countries is that trade with developing countries is an “energy subsidy” that will run out once developing countries are in a better negotiating position, leaving them with more costs to meet than resources to meet them with, in the same way populations subjugated by empires gain partial or full citizen status and become unsuitable for extraction.