Who Gets Self-Determination?

...

I.

LSE: Fact-Checking The Kremlin’s Version Of Russian History:

The notion that Ukraine is not a country in its own right, but a historical part of Russia, appears to be deeply ingrained in the minds of many in the Russian leadership. Already long before the Ukraine crisis, at an April 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, Vladimir Putin reportedly claimed that “Ukraine is not even a state! What is Ukraine? A part of its territory is [in] Eastern Europe, but a[nother] part, a considerable one, was a gift from us!” In his March 18, 2014 speech marking the annexation of Crimea, Putin declared that Russians and Ukrainians “are one people. Kiev is the mother of Russian cities. Ancient Rus’ is our common source and we cannot live without each other.” Since then, Putin has repeated similar claims on many occasions. As recently as February 2020, he once again stated in an interview that Ukrainians and Russians “are one and the same people”, and he insinuated that Ukrainian national identity had emerged as a product of foreign interference. Similarly, Russia’s then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev told a perplexed apparatchik in April 2016 that there has been “no state” in Ukraine, neither before nor after the 2014 crisis.

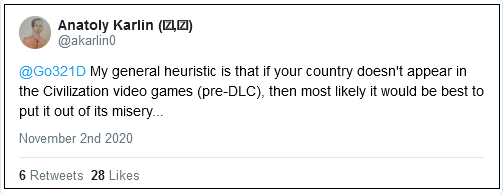

The article is from 2020, but the same discussion is continuing; see eg the New York Times’ recent Putin Calls Ukrainian Statehood A Fiction. History Suggests Otherwise. I’m especially grateful to the Russian nationalist / far-right blogosphere for putting the case for Ukraine’s non-statehood in terms that I can understand:

See also this comment by a reader of Karlin’s blog:

What exactly makes the Ukraine a nation? To just about everyone outside of Ukraine itself, no one can figure out what distinguishes Ukrainians from Russians. I’m not a Slavic language speaker, but I frequently hear about Ukrainian simply being a dialect of Russian or at least mutually intelligible. It should also be pointed out that English-language transliterations of Ukrainian words consistently look much worse than their Russian equivalents, and this is now ruining maps all over the world. Just from the standpoint of not wanting to ever see the cringe term “Kyiv” again one should avoid supporting the Ukrainians.

Now, it’s true that any LARP sustained long enough eventually becomes real. The Netherlands for instance was once German, and there’s even a parallel there with how Dutch consistently looks and sounds worse than German. So an independent Ukraine could, over time, become a real country. But to what end? Do we really need another mediocre Slavic country? It reminds me of Latin America, where you have dozens of barely distinguishable nonentity countries serving no real purpose. The entire region should be consolidated into maybe five states at most. Russia, Poland, and Serbia are the only Slavic states needed by the world.

The most “natural” way to organize states is around nationality, especially since the rise of mass communication. Where a state departs from this, it should be to realize some kind of interesting, cool, and distinct concept. Switzerland for instance is a confederation made up of pieces of three other nations, but the Swiss have created a highly interesting and distinct polity based on extreme decentralization, direct democracy, neutrality, and universal militia. For Switzerland to disappear would impoverish the world. But what is the objective in Ukraine? It is to become just another gay western democracy.

AP has the take that Visegrad shows the way. Integrating with the West to enjoy its security guarantees and material benefits, but developing your own civilization instead of destroying it. Press X for doubt. Viktor Orban might go down in the next election, and Polish conservatives appear to be doubling down on all of the dumbest mistakes of American Republicans.

So at the end of the day the Ukraine is fighting for the right to be objectively wrong, whereas Russia might be fighting to (re)establish a distinct civilizational space.

I appreciate hearing ideas I never would have thought of myself, and I never ever would have thought of this. I like how it simultaneously avoids starry-eyed “all people must be free” romanticism, and hard-headed “the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must” realpolitik, in favor of the vibe of some guy from a private equity firm trying to cut operating expenses: “Did anyone here notice that we have 195 countries, some duplicating each other’s portfolios? Do we really need both a Netherlands and a Belgium? And why do we still have an Egypt? People haven’t wanted Egypts for two thousand years!”

But the Ukrainian and Western response to all this has been to accept the paradigm, but argue that no, Ukraine does belong in Civilization games. For example, the LSE article says:

The territories of Ukraine remained a part of the Russian state for the next 120 years. Russia’s imperial authorities systematically persecuted expressions of Ukrainian culture and made continuous attempts to suppress the Ukrainian language. In spite of this, a distinct Ukrainian national consciousness emerged and consolidated in the course of the 19th century, particularly among the elites and intelligentsia, who made various efforts to further cultivate the Ukrainian language. When the Russian Empire collapsed in the aftermath of the revolutions of 1917, the Ukrainians declared a state of their own. After several years of warfare and quasi-independence, however, Ukraine was once again partitioned between the nascent Soviet Union and newly independent Poland. From the early 1930s onwards, nationalist sentiments were rigorously suppressed in the Soviet parts of Ukraine, but they remained latent and gained further traction through the traumatic experience of the ‘Holodomor’, a disastrous famine brought about by Joseph Stalin’s agricultural policies in 1932-33 that killed between three and five million Ukrainians. Armed revolts against Soviet rule were staged during and after World War II and were centred on the western regions of Ukraine that had been annexed from Poland in 1939-40. It was only with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 that Ukraine gained lasting independent statehood of its own – but Ukrainian de facto political entities struggling for their autonomy or independence had existed long before that.

Vox has a whole Voxsplainer about how ”Vladimir Putin says Ukraine isn’t a country. Yale historian Timothy Snyder explains why he’s wrong”, which is definitely the Vox-iest possible response to a deadly global conflict:

Ukrainian history goes way back before 1918. I mean, there are medieval events which flow into it, early modern events that flow into it. There was a national movement in the 19th century. All of that is, going back to your earlier question, all that falls into completely normal European parameters.

I find all of this unsatisfying. It’s like we’re debating whether a certain region has enough history and culture to “deserve” independence. But any such debate is inherently subjective. Does Texas qualify? Kurdistan? Scotland? Palestine? How should we know?

II.

As best I can tell, international law on this question centers around a UN-backed covenant which says that “all peoples have the right to self-determination”. So are Texans/Kurds/Scots/Palestinians a “people”? International law makes no effort to answer this question. Presumably Volodymyr Zelenskyy thinks Ukrainians count as a people, and Vladmir Putin isn’t so sure.

An International Court Of Justice judge, ruling on Kosovo, said:

[The definition of a “people”] is a point which has admittedly been defying international legal doctrine to date. In the context of the present subject-matter, it has been pointed out, for example, that terms such as “Kosovo population”, “people of Kosovo”, “all people in Kosovo”, “all inhabitants in Kosovo”, appear indistinctly in Security Council resolution 1244 (1999) itself. There is in fact no terminological precision as to what constitutes a “people” in international law, despite the large experience on the matter. What is clear to me is that, for its configuration, there is conjugation of factors, of an objective as well as subjective character, such as traditions and culture, ethnicity, historical ties and heritage, language, religion, sense of identity or kinship, the will to constitute a people; these are all factual, not legal, elements, which usually overlap each other.

So we sort of have a judge informally giving nine criteria for peoplehood. But the USA only satisfies four, and my group house satisfies five. So it probably needs some work.

Other sources have defined “a people” based on exclusion from existing political structures. So since Texans have all the normal rights in the US, they’re not a separate people. But since Palestinians don’t have all the normal rights in Israel, they are. But this suggests that if Putin invaded eg Finland, and then granted the Finns whatever the normal rights are in Russia, Finns would stop being a people.

(maybe this is predicated on the idea that a truly separate people, if given rights by a conqueror, would come up with some way to secede. But is this true? The “normal rights” in Russia are already very limited; if Putin oppresses everyone equally, and doesn’t single out Finns, then by these definitions he’s in the clear.)

Realistically “people” (like “obscenity” and everything else) are a kind of know-it-when-you-see-it combination of all these factors. I hate this. It means any would-be conqueror can say “come on, this place I want to conquer isn’t a real ‘people’” - and then you need to litigate annoying questions about exactly how glorious a history they had, and which version of Civilization they appeared in, in order to prove him wrong.

III.

Consider an alternative: everyone has the right to self-determination. If Ukraine prefers not to be part of Russia, they don’t have to be. We don’t have to consult the history books to determine whether or not their desire to maintain independence is valid.

This matches my intuitive ethical conception of self-determination. Suppose Putin’s historians found an old document in a file cabinet somewhere proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that Ukraine’s culture and history were not very glorious. My opinions about the moral status of this war would remain unchanged. Nothing I could learn about the Ukrainian language, religion, sense of kinship, ethnicity, or any of the other things that the judge in the Kosovo case mentioned, would make me feel good about Ukraine getting conquered by Russia

This feels so trivially true that it’s easy to miss how many big problems there are.

Does my street (population: ~100) have the right to declare independence from the USA? If not, then street-sized entities apparently don’t have the right to self-determination. Why not?

(maybe because although it has the moral right to do so, in practice this would be so annoying and unmanageable that we round this off to ‘no’? maybe the ‘transaction costs’ of facilitating my street’s independence are higher than the moral benefit? This paper makes some good points about how in order to have the right to secede, a group needs someone speaking for it who can credibly invoke this right. My street doesn’t have this - although any city with a mayor or city council does!)

Suppose dozens of US cities declared independence. The result would be lots of isolated enclaves with tiny markets and no ability to defend themselves. Those cities might wish that there was some pact keeping them together. So maybe since we already have such a pact (the general agreement that small regions can’t secede) we should stick to it.

(but if cities genuinely regret declaring independence, they can just rejoin. And even that implies cities are irrational and would declare independence when it wasn’t in their best interests. Why not just let cities do what they think best? Maybe they would even come up with some win-win solution, like independence plus EU-style union)

If my neighborhood declared independence from the US, China could offer to make us all multi-millionaires in exchange for hosting a military base on our territory. Doesn’t the US have the right to try to stop that?

(but doesn’t that imply that Putin has the right to invade Ukraine if he doesn’t like NATO on his borders? And China hasn’t tried putting a base in the Bahamas, probably because the US has soft power and threat-based ways of making sure that doesn’t happen. Wouldn’t it be fairer to make the US use soft power and threat-based ways of controlling my neighborhood, instead of outright annexation?)

And all these problems still exist in the current “peoples” paradigm. The Navajo are a “separate people” from other Americans by any definition, so under international law they have the right of self-determination. Why don’t they secede? I assume some combination of small size, economic self-interest, and US soft power/threats. So it turns out we’re fine at giving small populations the right to self-determination most of the time.

None of these big problems are the enormous problem, which is that international law isn’t really enforced, and existing countries have no incentive to change a rule which favors them, so this will definitely never happen. It’s almost a category error to even talk about it, as if there were some International Congress that made International Laws that the International Police would enforce.

Still, I think it’s useful to have an opinion on this. My opinion is that I’m in favor of the right of self-determination for any region big enough that it’s not inherently ridiculous for them to be their own country. I don’t care if they have their own language or ethnicity or glorious history, I will vote ‘yes’ before I even hear about any of those things. That means I don’t have to care about Putin’s argument for why he should get to have Ukraine.

IV.

But if you believe this, shouldn’t Russia get Crimea?

I’m nervous asserting that Crimea wants/wanted to join Russia. Russia put a lot of propaganda effort into making it look that way. The Crimean referendum (which did vote for the annexation) was held at gunpoint and produced implausibly enthusiastic results (96% in favor).

What about credible third-party assessments? As always, the exact percentages can change depending on what day you ask, and what wording you use, and what the other options are. But here’s an essay suggesting that most likely it does support annexation by a pretty big margin, and has done so for a long time. The area is 58% Russian ethnicity, mostly Russian-language-speaking, etc, so I find this plausible. If someone who knows more than me says it’s all propaganda, I might believe them. But my best guess right now is that 2014 Crimea probably did want to join Russia. Should it have been allowed to do so?

Again, I have trouble thinking of an ethical principle that says a group of people who really want to be part of Country A should in fact have to be part of Country B instead. I can disagree with Russia’s decision to force the matter with an invasion, and I can excuse Ukraine for not worrying about it too much. But overall I think I’m stuck consistently applying the principle “please let regions leave your country if you want”.

(is it meaningful that Crimea wanted to join Russia rather than become independent? I think no; if you agree they have a right to become independent, then they could become independent and then immediately join Russia; everyone agrees independent countries have the right to join other countries if they want)

The only way out of this conclusion is to double down on the “peoples” claim: Crimea isn’t distinct enough from the rest of Ukraine to be a separate “people”, so it shouldn’t be allowed to control its own destiny, so the historical accident that it ended up with Ukraine rather than Russia is sacrosanct. I think this is a weird reason to deny people the right to self-determination

“Maybe Crimea should belong to Russia” is a pretty spicy take to come out of an attempt to argue against Putin’s concept of nationalism. But it’s just the result of applying the same principle consistently.

V.

Somebody’s going to ask “but what about the Confederacy?” The position that most tempts me is “The Confederacy had every right to secede, because every region that wants to secede has that right - but immediately upon granting them independence, the Union should have invaded in order to stop the atrocity of slavery”. I say it tempts rather convinces because it suggests a moral duty to conquer any country doing sufficiently bad things (should the Union have invaded Brazil too, for the same reason?) I’m still not sure how I feel about this. Assuming we’re against invading foreign countries on principle, a utilitarian might refuse to let the Confederacy leave in the hope of preventing the establishment of a permanent slave power. But I would still think of that as one of those rights violation which utilitarians occasionally allow for the greater good.

In any case, I don’t think the answer to this question depends on whether Southerners qualify as a “different people” from Northerners, and I’m not sure the answer to any question should depend on that.