What Happened With Bio Anchors?

...

[Original post: Biological Anchors: A Trick That Might Or Might Not Work]

I.

Ajeya Cotra’s Biological Anchors report was the landmark AI timelines forecast of the early 2020s. In many ways, it was incredibly prescient - it nailed the scaling hypothesis, predicted the current AI boom, and introduced concepts like “time horizons” that have entered common parlance. In most cases where its contemporaries challenged it, its assumptions have been borne out, and its challengers proven wrong.

But its headline prediction - an AGI timeline centered around the 2050s - no longer seems plausible. The current state of the discussion ranges from late 2020s to 2040s, with more remote dates relegated to those who expect the current paradigm to prove ultimately fruitless - the opposite of Ajeya’s assumptions. Cotra later shortened her own timelines to 2040 (as of 2022) and they are probably even shorter now.

So, if its premises were impressively correct, but its conclusion twenty years too late, what went wrong in the middle?

II.

First, a refresher. What was Bio Anchors? How did it work?

In 2020, the most advanced AI, GPT-3, had required about 10^23 FLOPs to train.

(FLOPs are a measure of computation: big, powerful computers and data centers can deploy more FLOPs than smaller ones)

Cotra asked: how quickly is the AI industry getting access to more compute / more FLOPs? And how many FLOPs would AGI take? If we can figure out both those things, determining the date of AGI arrival becomes a matter of simple division.

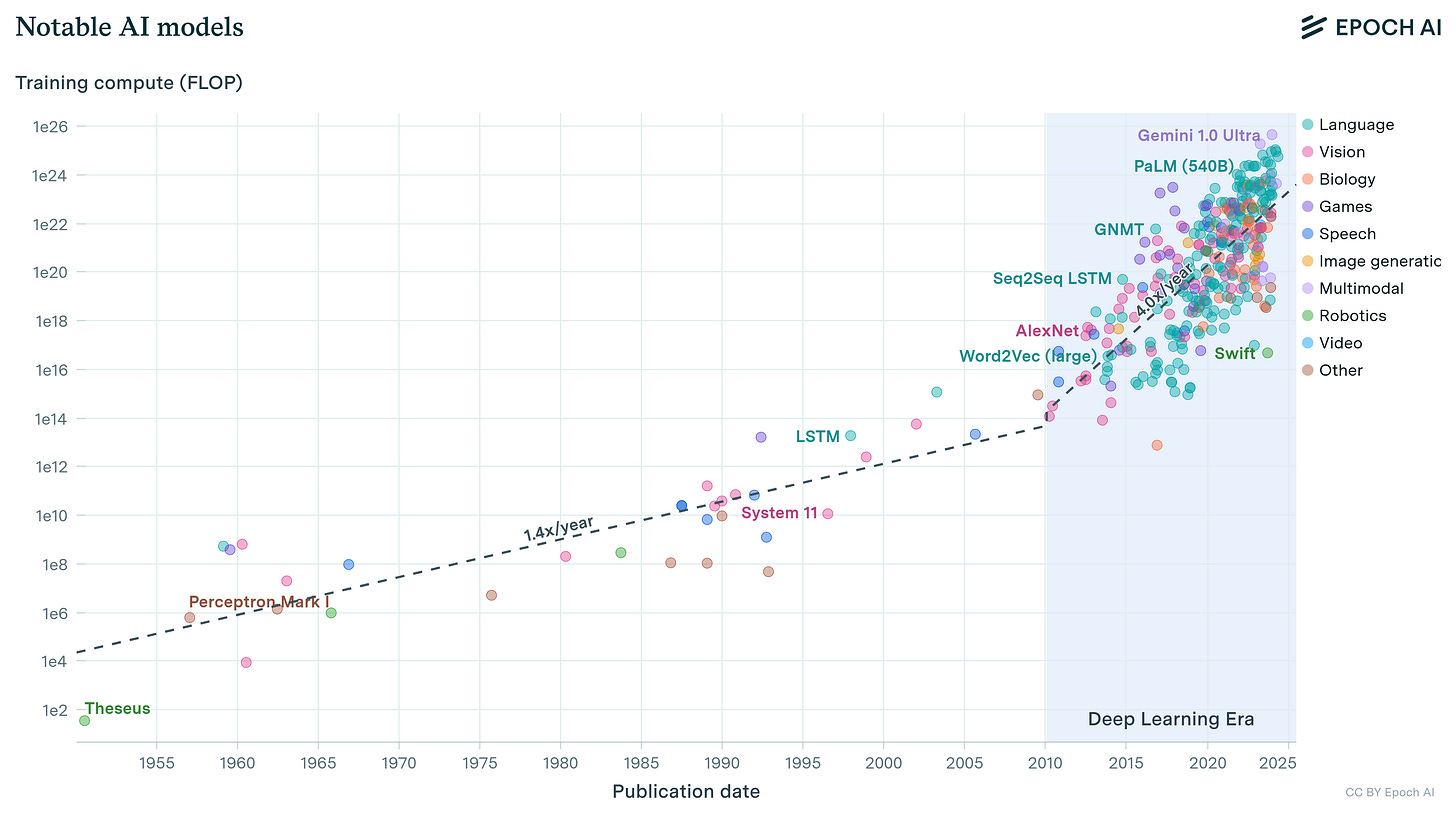

She found that FLOPs had been increasing at a constant rate for many years. And if you looked at planned data center construction, it looked on track to continue increasing at about that rate. New technological advances (algorithmic progress) made each FLOP more valuable in training AIs, but that process also seemed constant and predictable. So there was relatively constant growth in effective FLOPs (amount of computation available, adjusted by ability to use that computation efficiently).

There was no obvious way to know how many FLOPs AGI would take, but there were some intuitively compelling guesses - for example, an AGI that was as smart as humans might need a similar level of computing capacity as the human brain. Cotra picked five intuitively compelling guesses (the namesake Bio Anchors) and turned them into a weighted average.

Then she calculated: given the rate at which available FLOPs were increasing, and the number of FLOPs needed for AGI, how long until we closed the distance and got AGI?

At the time, I found this deeply unintuitive, but it’s held up! Improvement in AI since 2020 really has come from compute - the construction of giant data centers. Improvement in the underlying technology really has been measurable in “effective FLOPs”, ie the multiple it provides to compute, rather than some totally different incommensurable paradigm. And Cotra’s anchors - the intuitively compelling guesses about where AGI might be - match nicely with how far AI has improved since 2020 and how far it subjectively feels like it still has to go. All of the weird hard parts went as well as possible.

So, again, what went wrong?

III.

In 2023, Tom Davidson published an updated version of Bio Anchors that added a term representing the possibility of recursive self-improvement. The new calculations shifted the median date of AGI from 2053 → 2043. This doesn’t explain why our own timeline seems to be going faster than Bio Anchors: even 2043 now feels on the late side, and anyway recursive self-improvement has barely begun to have effects.

But in 2025, John Crox published a thorough report card on Davidson’s model. He took his numbers from Epoch, who used real data from the 2020 - 2025 period that earlier forecasters didn’t have access to, as well as the latest projections for what AI companies plan to do over the next few years. to with more formal projections. Most of his critiques apply to Bio Anchors too. We’ll be making use of them here.

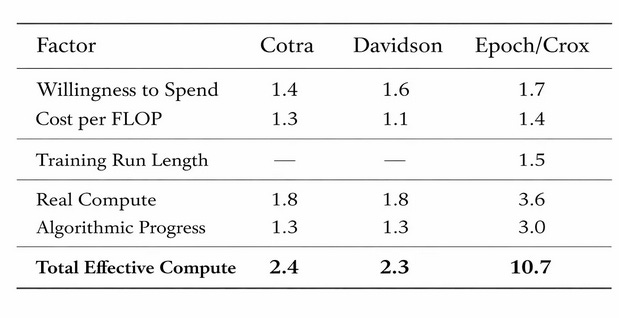

Crox found that Cotra and Davidson underestimated annual growth in effective compute:

All numbers are yearly multiples, so 1.4 means that willingness to spend grows 1.4x per year, ie 40%.

Willingness To Spend: How much money are companies willing to spend on AI, in the form of chips and data centers?

$/FLOP: How quickly do Moore’s Law, economies of scale, and other factors bring down the price of AI compute?

Training Run Length: How long are companies spending on AI training runs for frontier models (instead of using those chips for smaller models, experiments, or consumer services)?

Real Compute: The product of the three parameters above.

Algorithmic Progress: How effectively do researchers discover new algorithms that makes training AIs cheaper and more efficient?

Total Effective Compute: The product of real compute and algorithmic progress. So for example, the Epoch column’s 10.7x means that in any given year, you can train an AI 10.7x better than the last year, because you have 3.6x more compute available, and that compute is 3.0x more efficient.

Cotra and Davidson were pretty close on willingness to spend and on FLOPs/$. This is an impressive achievement; they more or less predicted the giant data center buildout of the past few years. They ignored training run length, which probably seemed like a reasonable simplification at the time. But they got killed on algorithmic progress, which was 200% per year instead of 30%. How did they get this one so wrong?

Here’s Cotra’s section on algorithmic progress:

Algorithmic progress forecasts

Note: I have done very little research into algorithmic progress trends. Of the four main components of my model (2020 compute requirements, algorithmic progress, compute price trends, and spending on computation) I have spent the least time thinking about algorithmic progress.

I consider two types of algorithmic progress: relatively incremental and steady progress from iteratively improving architectures and learning algorithms, and the chance of “breakthrough” progress which brings the technical difficulty of training a transformative model down from “astronomically large” / “impossible” to “broadly feasible.”

For incremental progress, the main source I used was Hernandez and Brown 2020, ”Measuring the Algorithmic Efficiency of Neural Networks”. The authors reimplemented open source state-of-the-art (SOTA) ImageNet models between 2012 and 2019 (six models in total). They trained each model up to the point that it achieved the same performance as AlexNet achieved in 2012, and recorded the total FLOP that required. They found that the SOTA model in 2019, EfficientNet B0, required ~44 times fewer training FLOP to achieve AlexNet performance than AlexNet did; the six data points fit a power law curve with the amount of computation required to match AlexNet halving every ~16 months over the seven years in the dataset.² They also show that linear programming displayed a similar trend over a longer period of time: when hardware is held fixed, the time in seconds taken to solve a standard basket of mixed integer programs by SOTA commercial software packages halved every ~13 months over the 21 years from 1996 to 2017.³

Grace 2013 (”Algorithmic Progress in Six Domains”) is the only other paper attempting to systematically quantify algorithmic progress that I am currently aware of, although I have not done a systematic literature review and may be missing others. I have chosen not to examine it in detail because a) it was written largely before the deep learning boom and mostly does not focus on ML tasks, and b) it is less straightforward to translate Grace’s results into the format that I am most interested in (”How has the amount of computation required to solve a fixed task decreased over time?”). Paul is familiar with the results, and he believes that algorithmic progress across the six domains studied in Grace 2013⁴ is consistent with a similar but slightly slower rate of progress, ranging from 13 to 36 months to halve the computation required to reach a fixed level of performance.

Additionally, it seems plausible to me that both sets of results would overestimate the pace of algorithmic progress on a transformative task, because they are both focusing on relatively narrow problems with simple, well-defined benchmarks that large groups of researchers could directly optimize.⁵ Because no one has trained a transformative model yet, to the extent that the computation required to train one is falling over time, it would have to happen via proxies rather than researchers directly optimizing that metric (e.g. perhaps architectural innovations that improve training efficiency for image classifiers or language models would translate to a transformative model). Additionally, it may be that halving the amount of computation required to train a transformative model would require making progress on multiple partially-independent sub-problems (e.g. vision and language and motor control).

I have attempted to take the Hernandez and Brown 2020 halving times (and Paul’s summary of the Grace 2013 halving times) as anchoring points and shade them upward to account for the considerations raised above. There is massive room for judgment in whether and how much to shade upward; I expect many readers will want to change my assumptions here, and some will believe it is more reasonable to shade downward.

Cotra’s estimate comes primarily from one paper, Hernandez & Brown, which looks at algorithmic progress on a task called AlexNet. But later research demonstrated that the apparent speed of algorithmic progress varies by an order of magnitude based on whether you’re looking at an easy task (low-hanging fruit already picked) or a hard task (still lots of room to improve). AlexNet was an easy task, but pushing the frontier of AI is a hard task, so algorithmic progress in frontier AI has been faster than the AlexNet paper estimated.

In Cotra’s defense, she admitted that this was the area where she was least certain, and that she had rounded the progress rate down based on various considerations when other people might round it up based on various other considerations. But the sheer extent of the error here, compounded with a few smaller errors that unfortunately all shared the same direction, was enough to throw off the estimate entirely.

Since Cotra and Davidson were expecting AI to get 3.6x better every year, but it actually got 10.7x better every year, it’s no mystery why their timelines were off. When John recalculates Davidson’s model with Epoch’s numbers, he finds that it estimates AGI in 2030, which matches the current vibes.

IV.

With this information in place, it’s worth looking at some prominent contemporaneous critiques of Bio Anchors.

Various people criticized Bio Anchors’ many strange anchors for how much compute it would take to produce AGI. For example, one anchor estimated that it would take 10^45 FLOPs, because that was how many calculations happened in all the brains of all animals throughout the evolutionary history (which eventually produced the human brain that AIs are trying to imitate). To make things even weirder, this anchor assumed away all animals other than nematodes as a rounding error (fact check: true!)

All of these seemed to detract from the main show, an attempt to estimate the compute involved in the human brain. But even this more sober anchor was complicated by time horizons - it’s not enough to imitate the human brain for one second; AIs need to be able to imitate the human brain’s capacity for long-term planning. Cotra calculated how much compute AGI would require if it needed a planning horizon of seconds, weeks, or years.

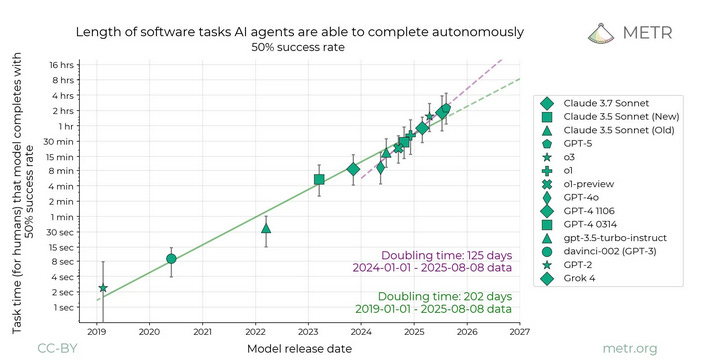

Thanks to METR, we now know that existing AIs have already passed a point where they can do most tasks that take humans seconds, are moving through the hour range, and are just about to touch one day. So the “seconds” anchor is ruled out. But it also seems unlikely that AGI will require years, because most human projects don’t take years, or at least can be split into tasks that take less than one year each (intuition pump: are we sure the average employee stays at an AI lab for more than a year? If not, that proves that a chain of people with sub-one-year time horizons can do valuable work). The AI Futures team guessed that the time horizon necessary for AIs to really start serious recursive self-improvement was between a few weeks and a few months (though this might look like a totally different number on the METR graph, which doesn’t translate perfectly into real life). If this is true, then all three anchors (seconds, hours, years) were off by at least an order of magnitude.

But it turns out that none of this matters very much. The highest and lowest anchors cancel out, so that the most plausible anchor - human brain with time horizon of hours to days - is around the average. If you remove all the other anchors and just keep that one, the model’s estimates barely change.

But also, we’re talking about crossing twelve orders of magnitude here. The difference between the different time horizon anchors doesn’t register much on that level, compared to things like algorithmic progress which have exponential effects.

Maybe this is the model basically working as intended. You try lots of different anchors, put more weight on the more plausible ones, take a weighted average of each of them, and hopefully get something close to the real value. Bio Anchors did.

Or maybe it was just good luck. Still hard to tell.

Eliezer Yudkowsky argued that the whole methodology was fundamentally flawed. Partly because of the argument above - he didn’t trust the anchors - but also partly because he expected the calculations to be obviated by some sort of paradigm shift that couldn’t be shoehorned into “algorithmic progress” (like how you couldn’t build an airplane in 1900 but you could in 1920).

As of 2026 - still before AGI has been invented and we get a good historical perspective - no such shift has occurred. The scaling laws have mostly held; whatever artificial space you try to measure models in, the measurement has mostly worked in a predictable way. There have really only been two kinks in the history of AI so far. First, a kink in training run size around 2010:

Second, a kink in time horizons around 2024 and the invention of test-time compute:

The 2010 kink was before Cotra’s forecast and priced in. The 2024 kink is interesting and relevant, but I don’t think it rises to the level of paradigm-busting insight that I interpreted Yudkowsky as predicting. Since it was on a parameter Cotra wasn’t measuring, and probably too small to show up on the orders-of-magnitude scale we’re talking about, it’s probably not a major cause of the model’s inaccuracy.

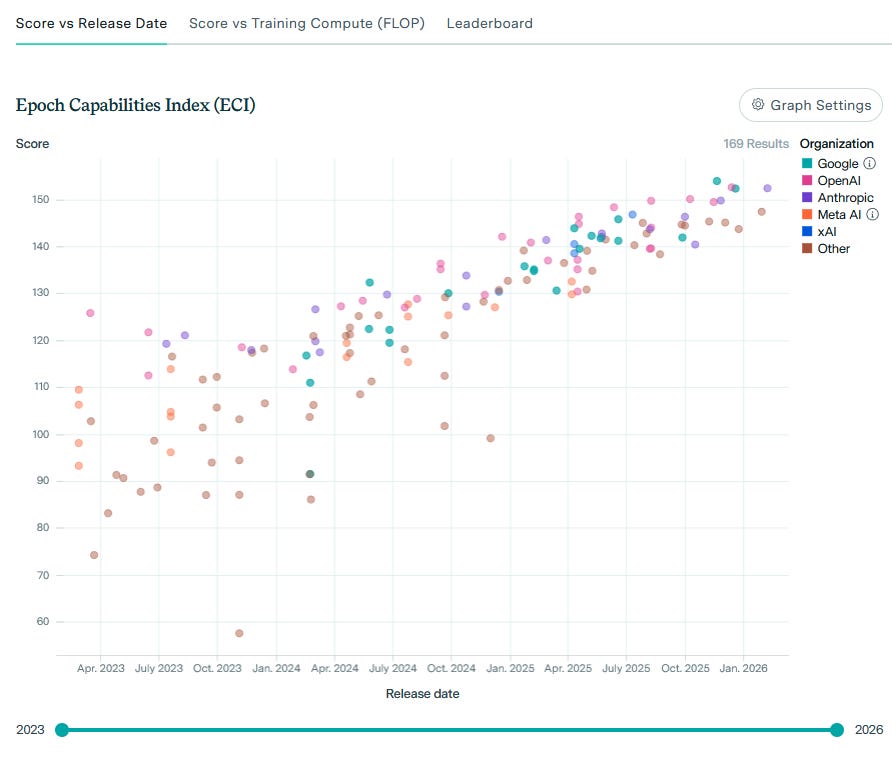

Other things have been even more predictable:

So Cotra’s bet on progress being smooth and measurable has mostly paid off so far.

But Yudkowsky further explained that his timelines were shorter than Bio Anchors because people would be working hard to discover new paradigms, and if the current paradigm would only pay off in the 2050s, then probably they would discover one before then. You could think of this as a disjunction: timelines will be shorter than Cotra thinks, either because deep learning pays off quickly, or because a new paradigm gets invented in the interim. It turned out to be the first one. So although Yudkowsky’s new paradigm has yet to materialize, his disjunctive reasoning in favor of shorter-than-2050 timelines was basically on the mark.

Nostalgebraist argued that Cotra’s whole model was a wrapper for an assumption that Moore’s Law will continue indefinitely. If it does, obviously you get enough compute for AI at some point, even if it requires some absurd process like simulating all 500 million years of multicellular evolution.

I never entirely understood this objection, because - although Bio Anchors does depend on a story where Moore’s Law doesn’t break before we get the relevant amount of compute - this is only one of many background assumptions (like that a meteor doesn’t hit Earth before we get the relevant amount of compute). Given those assumptions, it does a useful not-just-assumption-repeating job of calculating when transformative AI will happen.

As Cotra implicitly predicted, we seem on track to get AGI before Moore’s Law breaks down, and so Moore’s Law didn’t end up mattering very much. And if all of Cotra’s non-Moore’s-Law parameter estimates had been correct, her model would have given about the same timelines we have now, and surprised everyone with a revolutionary claim about the AI future.

But Nostalgebraist added, almost as an aside:

Cotra has a whole other forecast I didn’t mention for “algorithmic progress,” and the last number is what you get from just algorithmic progress and no Moore’s Law. So depending on how much you trust that forecast, you might want to take all these numbers with an even bigger grain of salt than you’d expected from everything else we’ve seen.

How much should you trust Cotra’s algorithmic progress forecast? She writes: “I have done very little research into algorithmic progress trends. Of the four main components of my model (2020 compute requirements, algorithmic progress, compute price trends, and spending on computation) I have spent the least time thinking about algorithmic progress.” ...and bases the forecast on one paper about ImageNet classifiers.

I want to be clear that when I quote these parts about Cotra not spending much time on something, I’m not trying to make fun of her. It’s good to be transparent about this kind of thing! I wish more people would do that. My complaint is not that she tells us what she spent time on, it’s that she spent time on the wrong things.

Like Cotra herself, I think Nostalgebraist was spiritually correct even if his bottom line (about Moore’s Law) was wrong. His meta-level point was that a seemingly complicated model could actually hinge on one or two parameters, and that many of Cotra’s parameter values were vague hand-wavey best guess estimates. He gave algorithmic progress as a secondary example of this to shore up his Moore’s Law case, but in fact it turned out to be where all the action was.

V.

Those were the rare good critiques.

The bad critiques were the same ones everyone in this space gets:

You’re just trying to build hype.

You’re just trying to scare people.

You use probabilities, but probabilities are meaningless and just cover up that you don’t really know.

AI forecasts are just attempts for people to push AGI back to some time when it can’t be checked.

AI forecasts are just attempts for people to pull AGI forward to when it means they personally will live forever.

The impressive thing here is that correcting the estimates of two parameters - compute growth and algorithmic progress - produce a forecast which would have seemed valuable and prescient six years later. Even correcting one parameter - algorithmic progress - would have gotten it very close. In that sense, the history of Bio Anchors is a white pill for forecasting, and an antidote to the epistemic nihilism of the positions above.

But its bottom line was still wrong. Even if you do almost everything correctly, invent new terms that become load-bearing pillars of the field, defeat your critics’ main objections, and demonstrate a remarkably clear model of exactly how to think about a difficult subject, mis-estimating one parameter can ruin the whole project.

This is why you do a sensitivity analysis, and Cotra did this at least in spirit (talked about which parameters were most important; gave people widgets they could use to play around with). But it didn’t work as well as she might have hoped, giving a <10% chance of timelines as short as the current median. Several later commenters and analysts had good takes here, especially Marius Hobbhahn of Apollo Research. Along with correctly guessing that algorithmic progress would go faster than Bio Anchors predicted (albeit with the benefit of two more years of data), he wrote that:

The uncertainty from the model is probably too low, i.e. the model is overconfident because core variables like compute price halving time and algorithmic efficiency are modeled as static singular values rather than distributions that change over time.

Plausibly if these had been distributions, you could have done a more formal sensitivity analysis on them, and then it would have identified these as crucial terms (Nostalgebraist unofficially noticed this, but a formal analysis could have officially noticed and quantified it) and had more uncertainty about the possibility of very early AGI.

So what’s the takeaway? Trust forecasts more? Trust them less? Do better forecasting? Don’t bother?

These questions have no right answer, but one conclusion does seem pretty firm. Most of the bad-faith critics, having identified that Ajeya’s model was imperfect and could fail, defaulted to the Safe Uncertainty Fallacy - since we can never be sure a model is exactly right, things are uncertain, which means we can continue to believe everything is fine and normal and timelines are wrong and we don’t have to worry. But as Yudkowsky pointed out, there’s uncertainty on both sides! Sometimes the fact that a forecast is imperfect and you can never be certain means things are more dangerous than you thought!

I think internalizing this lesson is more important than any sort of micro-calibrating exactly how much to believe in probabilistic forecasts. Once you understand that you can’t always just rely on your biases and sense that it would be inconvenient for things to get weird, you become desperate for real information. That desperation encourages you to seek any possible source of knowledge, including potentially fallible and error-laden probabilistic forecasts. It also encourages you to treat them lightly, as small updates useful for resolving near-total uncertainty into merely partial uncertainty. This is how I treat Bio Anchors’ successors - although right now a little more fallibility and error-ladenness might be genuinely welcome.