Yeah, I know you’re saturated with Ukraine content. Yeah, I know everyone wants to relate their hobbyhorse to Ukraine. But I think it’s genuinely useful to talk about prediction markets right now.

Current conventional wisdom is that the invasion was a miscalculation on Putin’s part, after he surrounded himself with so many yes-men that he lost touch with reality. But Ukraine miscalculated too; until almost the day of the invasion, Zelenskyy was saying everything would be okay. And if there’s a nuclear exchange, it will be because of miscalculation - I don’t know what the miscalculation will be, just that nobody goes into a nuclear exhange because they want to. Preserving people’s access to reality and helping them avoid miscalculations are peacekeeping measures, sometimes very important ones.

The first part of this post looks at various markets’ predictions of how the war will go from here (Zvi published something like this a few hours before I could, so this will mostly duplicate his work). The second part very briefly tries to evaluate which markets have been most accurate so far - though this is a topic which deserves at least paper-length treatment. The third part looks at which pundits deserve eternal glory for publicly making strong true predictions, and which pundits deserve . . . something else, for doing . . . other things.

Part I: Warcasting

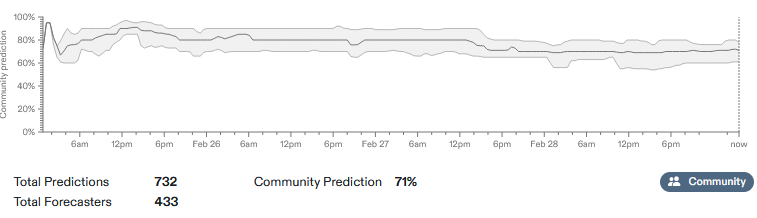

Starting with Metaculus:

— Will Kyiv fall to Russian forces by April 1 2022? 69% chance

This is the most-predicted relevant question on Metaculus right now. The first day of the war, the market predicted as high as 90%; as people realized the strength of Ukrainian resistance, it fell to 80. Mid-Saturday there was a sudden drop from 78% to 72%, after some combination of a defiant Zelenskyy speech and a report that Russian paratroopers had been repelled. Since then it’s barely budged.

— Will at least three of six big Ukrainian cities fall to Russian forces by June 1? 71% chance

The six cities are Kyiv, Odesa, Lviv, Mariupol, Kharkiv, and Kherson. This question gives the Russians two more months than the last one, so it’s surprising that they’re at about the same probability. Maybe everyone expects Russia to go for Kyiv first and take longer for anything else? Or maybe they’re assuming everything stands or falls together.

— Will WWIII happen before 2050? 20% chance

This question defines “World War III” as any war whose combatants have 30% of world GDP or 50% of world population, and in which 10 million people die. Over the past two years, the question has bounced between about 7 and 19 percent. Today it’s at 20%, its highest value ever - but still only a single-digit percent above its baseline.

— Will Russia invade any country other than Ukraine in 2022? 12% chance

Commenters bring up Belarus (if they start seeming less loyal), Moldova (if part of Russia’s plan was to create a corridor to Transdnistria), or Georgia (Russia likes invading Georgia). Relatively few people think a Russia-NATO war is likely to be a big part of this. Zvi thinks this should be 20%.

— Will Putin still be president of Russia next February? 71% chance

This started at 85% and has been getting gradually lower, but it suffers for lack of pre-war data to compare it to. Here’s a related question asking forecasters to predict when Putin will leave power. Through most of last year, it averaged 2027 - 2029; now it’s at 2024. I imagine this is too weird a mixture of early and late guesses to interpret clearly, but the downward trend sure is obvious.

— Will 50,000 civilians die in any single Ukrainian city? 8% chance

Forecasters are optimistic this will not happen. A commenter mentions that only 30,000 civilians died in Aleppo during four years of fighting there.

Other sites have fewer or less trustworthy markets, but here’s a selection:

— Will Zelensky still be President of Ukraine on 4/22/22? 42% chance

Polymarket seems hesitant to go into actual war predictions, but this market at least acts as a proxy for whether there will be a Ukraine on 4/22/22 - though with a side of “will Zelensky be killed or captured?”. “Yes” dropped as low as 12% during the early parts of the invasion, but is doing a little better now.

— Will Russia control Kyiv on 4/2/22? 54% chance

This is Manifold’s biggest Ukraine market right now. It’s very similar to the biggest Metaculus question, although the resolution criteria are different (Metaculus: 6/10 raions; Manifold: informal, whether Duncan says so). I don’t know if that fully explains the different probabilities: 69% chance on Metaculus vs. 54% chance on Manifold. In the past when Metaculus and Manifold disagreed I’ve eyeballed Metaculus as being more accurate, but few data points so far.

There’s a Putin ouster market that has exactly the same probability as Metaculus', and a very small “will Russia invade anywhere else” market that’s at 30% right now, more than twice Metaculus’ level.

Meanwhile, searching for Ukraine on Kalshi gives me nothing, so please accept their “will it be over 35 degrees in New York City” market instead. Everyone keeps telling me I shouldn’t be so bearish on Kalshi, they can be both regulated and dynamic at the same time. Maybe so, but not yet.

Part 2: Prediction Market Comparisons

Clay Graubard did some good work looking at how different prediction markets assessed the threat of Russia invading Ukraine.

These are hard to directly compare since they ask slightly different questions (eg end date). Some people would call it unlikely that Russia didn’t attack Ukraine this month, but then did in summer/fall 2022; it would require that they mass a bunch of troops on the border, send them home again (they can’t support them all there indefinitely), then bring them back a few months later for the real invasion. With that assumption, all possible invasions would be near-term invasions and you could compare these markets fairly; without that assumption, it’s hard to say.

I would add that Manifold did worse than any of these; it was at 36% on 2/14, and barely made it to 50% before the actual invasion happened.

Another thing you can do with this graph is notice which markets react more vs. less to news. For example, INFER seems totally unreactive; it’s just a vaguely upward-trending line the whole time - I don’t know enough about it to have a good sense of why that would be. Meanwhile, GJI (superforecasters) seem the most reactive. I don’t have a good sense of how to think about this or whether reactivity is necessarily good.

My main takeaways are that markets should coordinate to have similarly-phrased questions to make them easier to compare, and that - given that Metaculus and Manifold are the two places with the most markets right now - we should trust Metaculus more than Manifold until further notice. Metaculus also comes out looking good compared to Good Judgment and the superforecasters, though I can’t tell how much of this is question wording vs. a real advantage.

Oh, and if Clay says there’s going to be a war, head for the bunkers.

Part 3: Pundit Accountability

Part of the point of turning forecasting into a formal science is Philip Tetlock’s observation that pundits do such a bad job. They don’t seem to be right more often than chance, and even when they’re confidently wrong everyone keeps listening to them.

Trying to celebrate or condemn pundits is a dangerous game; you risk over-updating on individual questions. If you look at the 2016 election in isolation, Scott Adams is the smartest guy in the world; if you look at it in context, Scott Adams likes saying crazy things very confidently, and sometimes those crazy things happen. This is going to be the out-of-context one: still, I think it’s better than nothing.

Since I’m claiming the right to judge others, it’s fair to ask how I performed. The answer is: medium! On my Predictions For 2022, posted January 31, I said there was a 50-50 chance of a “major flare-up in the Russia/Ukraine conflict” this year (obviously this qualifies). Later, I quoted Matt Yglesias’ prediction (40% chance of Russia invading Ukraine) and said HOLD, ie I didn’t disagree in either direction. A charitable person would interpret that as me saying there was a 50% chance of a major flare-up, of which 10% was a “flare-up” short of full invasion, and 40% was invasion. In reality, I just forgot I’d assigned a higher probability to that statement earlier and consulted an extremely vague mental model where 50% sounded right but 40% also sounded right. So I assigned an invasion somewhere between 40-50% probability on January 31. Most prediction markets were also around that level then (Metaculus was 44%). I didn’t let myself check markets when making my prediction, but I’d probably glanced at them before. In any case, I made the conservative prediction of “yeah, fine, whatever everyone else is saying”.

As part of the same(-ish) series of predictions, Matt Yglesias gave a 40% chance that Russia would invade Ukraine in January; Zvi gave a 30% chance in February.

I made a small amount of fake money and a smaller amount of real money betting “YES” on a few prediction markets, after writing this post and being annoyed that they seemed too low, but this was just arbitrage, not a real opinion.

That having been said, let’s move on to the pundits who took interesting and strong positions, starting with:

Edward Luttwak: C

This is the guy who wrote Coup D’Etat, a handbook for attempting coups. He is a famous international relations and geopolitics theorist, has served in the IDF, speaks six languages, and has written a book on the military strategy of the late Roman Empire. I read his coup handbook a while ago and was very impressed by him.

Luttwak correctly predicted that Russia would have a hard time invading Ukraine with its current troop numbers, but incorrectly predicted that, because “Putin is not a fool”, they wouldn’t try. When everyone else expected Russia to win instantly, Luttwak was the only person I saw arguing (again and again) that conquering Ukraine would actually be very hard and Putin might fail. He deserves honor and glory for that strong, public, and accurate prediction.

Still, I’m giving him a C, because he equally strongly predicted Russia wouldn’t invade, even calling the intelligence community “hysterical” and “always wrong”. I tend to be sympathetic to people who are honestly wrong - even wrong when they give high probabilities - and much less sympathetic to people who are wrong while insulting everyone else for disagreeing with them.

Maybe the lesson here is that expertise (at least in military matters) is real, but extremely circumscribed. Luttwak is exactly the sort of guy who I expect to know how many troops it takes to invade a country, but I’m not sure why he should be an expert in Putin’s psychology and maybe he was so reliant on his military expertise that he made a (false) assumption of Putin’s rationality in order to be able to carelessly jump from “I know a lot about military strategy” to “I can predict what Putin will do”.

Anatoly Karlin: B-

Anatoly is a Russian nationalist who wrote Regathering Of The Russian Lands, which has become the canonical (in these circles) essay for understanding how Putin thinks.

He got the opposite pattern from Luttwak: totally right about what Putin would do, but his predictions about weak Ukrainian resistance are on the verge of being disproven.

He argues that the West is overestimating Ukraine - Russia is closer to Kyiv than America was to Baghdad at this stage of their Iraq invasion, and everyone was impressed with that stage of the American campaign. But he was intellectually honest enough to give a very specific prediction - collapse of Ukrainian resistance within a week - so he can’t really get out of admitting he miscalculated here. I definitely think both these things can be true at once: the Russians underestimated the extent of Ukrainian resistance even as the West may be overestimating it.

Just as Luttwak had many reasons to be right about war but might not have known much about Putin’s personality, so Karlin has every reason to be right about Putin’s personality, but isn’t really much of a military strategy expert. I’m giving him a slightly higher grade because he was more self-aware and made more specific predictions.

Richard Hanania: B-

See his Lessons From Forecasting The Ukraine War.

Like Karlin, Hanania correctly guessed early on that Putin would invade Ukraine. On February 2, when Metaculus was at 49% (and I was 40 - 50%), Hanania said 65% chance. Over the next few weeks, he increased his probability at the same rate as the average, so that just before the war started he was giving it 95% chance. This is very impressive - both because he was right, and because of how careful, honest, and public he was with his predictions.

On his Lessons post, he wrote:

I’m proud of my record forecasting the invasion, given that it went against most of the predictions of those who generally share my foreign policy views. Anyone can occasionally be correct by following the same heuristic they always use, but I showed intellectual flexibility here by determining that American intelligence was likely correct. Karlin is the only other prominent US foreign policy skeptic I know of who thought war was even more likely than the conventional wisdom suggested, and he deserves credit for that (if you know of others, mention them in the comments). Part of the reason I came to the right conclusion was that I was even more pessimistic than most anti-interventionists were about the degree of rationality present in American foreign policy. For example, my friend Max Abrahms was saying until very recently that Putin was hoping for some concessions that would allow him to avoid war (to be fair, Max has been more correct than me on the invasion running into difficulties). I thought that was possible too, but I had little hope that American politics would allow Biden to strike a deal. When it became clear that negotiating over the NATO open door policy wasn’t even on the table, I increased my estimate of the probability for war. To his credit, Max has admitted I was right, as have others I’ve been texting with over the last few months. I also give credit to Saagar, Philippe, and Michael Tracey for publicly acknowledging mistakes.

As I’ve said before, “trust the experts” and “don’t test the experts” are both bad heuristics (see the Substack article and its NYT version). Talking to anti-interventionists about the potential for a Russian invasion throughout January and February, I was struck by how often they would ignore my arguments and instead say things like “this guy has always been right, so I’m going to trust him.” That might be an adequate strategy when you have nothing else to go on, but here we had a lot of evidence relevant to what was likely to happen, including satellite imagery of military movements and reports on the state of diplomatic negotiations. I’ve found one of the most insightful analysts throughout the crisis to be Dmitri Alperovitch. But when I shared one of his tweets with a very intelligent friend of mine, his response was basically “his profile says that he is affiliated with Crowdstrike, which was involved in the Russiagate hoax. How can we believe anything he says?” I can understand the reaction, but it seems like this kind of thinking led many intelligent observers astray.

Still, like Karlin, he flubbed the Ukrainian resistance. In Russia As The Great Satan In The Liberal Imagination (subtitled: “Why the culture war is global and there will be no insurgency in Ukraine”) he wrote:

Once we step aside from culture war resentments and focus on the hard realities of geopolitics, it is clear that Russia will eventually get its way because it cares more about Ukraine than the US does, and has the ability to threaten or use military force to get what it wants. When resolve and capabilities line up on the same side, that side is going to win. And the reason that Americans don’t care about Ukraine is that Ukraine objectively does not matter to the US. All the sophistry in the world coming from MSNBC hosts, ex-generals on the payrolls of defense contractors, and think tank analysts can’t change people’s perceptions here.

The only questions now are how far Putin will go, and how tough American sanctions will be. Washington is now deluding itself into believing that it can help facilitate an insurgency in Ukraine. This will not happen. One of the best predictors of insurgency is having the kinds of terrain that governments cannot reach, like swamps, forests and mountains. Ukraine is the heart of the great Eurasian steppe […] Even setting aside the geography of the country, there is no instance I’m aware of in which a country or region with a total fertility rate below replacement has fought a serious insurgency. Once you’re the kind of people who can’t inconvenience yourselves enough to have kids, you are not going to risk your lives for a political ideal.

On his more recent post, he wrote:

Regarding the prediction that there would be no insurgency, it is not technically false yet, since the conventional phase of the war is still ongoing, but I have to be honest and say that I expected a lot less fighting than we’re seeing. As already mentioned, I thought it might be like the fall of Kabul, where the weaker side just melted away even if it could’ve theoretically held out longer. But the Afghan government was probably uniquely bad, and the fact that it performed so poorly didn’t mean that Ukraine was a fake nation or that no one would fight for its government. A clue should’ve been that, although the Afghan government was losing territory even with American support, Ukraine had been doing an adequate job in its own defense since 2014 and holding its own in the war in the Donbas.

My argument that Ukraine did not have a high enough TFR to tolerate the casualties required for an asymmetric conflict may well have been motivated reasoning, based on my view that not having enough children is a sign of moral and spiritual decline. We’ll see soon enough if the view was well founded or not, as a Ukrainian collapse is still possible, even if it takes longer than I would have thought. Similarly, a source of wishful thinking here might have been my suspicion that, if there was a more sustained conflict, it would mean a great deal of Western involvement, which would raise the risk of nuclear war.

His performance is basically the same as Karlin’s, and I’m giving him the same grade.

Dmitri Alperovich: B+

Alperovich is a Russian-American cybersecurity executive. When I asked in an Open Thread, several people named him as one of the people who most consistently predicted invasion.

Is he an exception to the rule that people who got the invasion right got the resistance wrong and vice versa? I’m not sure. He didn’t talk much about how Ukrainian resistance would go, although see here:

Still, I think he comes out the best overall of anyone on this list.

Tyler Cowen: ???

This tweet has been going around recently:

But it’s from February 21. On February 21, Putin announced he was sending “peacekeepers” in to Donbass. Most sources say the invasion of Ukraine started February 24.

I am having trouble finding evidence of Tyler saying other specific things. On February 12, he posted this quote, which seemed to maybe suggest Russia would invade around the 20th. On February 17th, he wrote:

I think the correct model here is “Putin has put down so many chips, he can’t walk away with nothing. He wants to wreck Ukraine (more than taking territory per se). He will do the minimum amount he can that leaves him with a strong probability of having wrecked Ukraine, and no more.” That still leaves a broad range of possible outcomes, but at the moment that is my mental model for updating with new information.

Is the current invasion “the minimum amount he can [do] that leaves him with a strong probability of having wrecked Ukraine”?

But on February 24, he made an extremely strong prediction whose truth has yet to be determined:

I would start with two observations:

1. Putin’s goals have turned out to be more expansive than many (though not I) expected.

2. There are increasing doubts about Putin’s rationality.

I’ll accept #1, which has been my view all along, but put aside #2 for the time being.

In my simple model, in addition to a partial restoration of the empire, Putin desires a fundamental disruption to the EU and NATO. And much of Ukraine is not worth his ruling. As things currently stand, splitting Ukraine and taking the eastern half, while terrible for Ukraine (and for most of Russia as well), would not disrupt the EU and NATO. So when Putin is done doing that, he will attack and take a slice of territory to the north. It could be eastern Estonia, or it could relate to the Suwalki corridor, but in any case the act will be a larger challenge to the West because of explicit treaty commitments. Then he will see if we are willing to fight a war to get it back. There are fixed costs to mobilization and incurring potential public wrath over the war, so as a leader you might as well “get the most out of it.” Our best hope is that the current Russian operations in Ukraine go sufficiently poorly that it does not come to this.

I am mildly annoyed by Tyler being much less clear than (eg) Richard or Anatoly in making specific assertions, yet also claiming the mantle of a prescient predictor. Still, if what he says about the Suwalki Corridor comes to pass, I will give him the mantle.

(if it doesn’t, he can just say it was because the current Russian operations in Ukraine went sufficiently poorly. Have I mentioned being mildly annoyed?)

Samo Burja: C

Samo is a rationalist success story and a smart guy, and I appreciate most of his takes. And he’s been careful not to say anything specific that might later get proven false.

Still, I think his biggest position going into this war was “Russia Strong”:

Events seem to be tending in the “Russia Not Strong” direction compared to where they were a week or two ago. Even if Russia wins - which they still might do! - and even if Anatoly is right that Western propaganda has us underestimating Russian military successes, I think perceptions of the competence of their army, their ability to match NATO, and their geopolitical acumen have taken a hit.

(for another super-interesting take on Samo’s article on Russian military reforms, see Kamil Galeev here)

When I say he is careful not to say anything specific that might be proven false, this isn’t exactly a compliment. I think it’s better optics, but worse rationality, compared to people like Karlin and Hanania who make extremely clear predictions with numbers attached, sometimes get them totally wrong, and then admit it and write thoughtful essays on how they screwed up. Like Tyler Cowen, Samo is going for the “shadowy Machiavellian genius” role, which gives him a strong incentive to avoid humiliation. But part of our civilizational immune system against shadowy Machiavellian genius figures is demanding that they do this even when they would prefer not to! I like Samo enough (and have enough probability on him actually being a shadowy Machiavellian genius) that I want him to up his game!

Lindyman: D-

The only reason this isn’t an F is that I assume LindyMan plagiarized it from someone else, and I don’t want to blame him for their mistake.

Michael Tracey: D

Tracey at least wrote a thoughtful reflection on his failed prediction, which you can find here:

I also want to acknowledge the obvious: that the main theme of my reporting and commentary on this issue has been major skepticism toward the US Government and media, particularly in their prognostications of an “imminent” invasion. I still maintain there’s much to criticize — it strikes me as very conceivable that this constant barrage of maximalist predictions could have perversely influenced Putin’s calculations. Premature statements of fact by politicians and pundits that an invasion had already occurred, when it had not yet occurred, were reckless in such fraught circumstances. Journalists who abused their access to “official” anonymous sources did the opposite of inspiring confidence in the stark warnings they were pumping out. And so on and so forth. But yes, it has to be said: the official prophecies have in fact been tragically borne out.

I’ll need to reflect more on the implications of this outcome. All I can promise you is transparency, honesty, and a willingness to correct for any blindspots. One potential blindspot here was placing too much emphasis on the repeated and vehement criticism by actual Ukrainian officials of what they decried as alarmist US rhetoric. Just last week, I interviewed a sitting member of the Ukraine parliament who straight-up told me that externally-generated “panic” was a far greater threat to Ukraine’s security than any forthcoming Russian invasion. Ukraine’s president, over and over again, was even more searing in his own repudiations of US government and media behavior. I don’t have a great explanation for this dynamic yet, but it’s possible what they were telling me tracked too closely with my pre-existing disdain for official US claims vis-a-vis Russia — which in the very recent past have been wildly wrong and destructive. As you’ll remember if you lived through Russiagate.

I did try to qualify much of what I said on this topic to allow for the possibility that an invasion could in fact take place. In a February 10 article here on Substack, I wrote that a Russian escalation was “ominously plausible.” And I still think the formulation in this tweet from January 23 is very much legitimate:

It's of course possible that Russia does plan to invade Ukraine and install a new government, but this conclusion largely derives from US and "Western" intelligence sources, which don't exactly have a good recent track record of providing trustworthy information related to RussiaStill, I can understand why people who only caught snippets of certain tweets thought I was a 100% incorrigible “invasion denier.” I never denied the possibility of an invasion — again, I always made a point to explicitly allow for that very possibility. But the reality of online “content production” is that observers will impressionistically pick up on broad themes you seem to be projecting, and if real-world events appear to contradict the impression of you they’ve developed, they will conclude you’ve been proven disastrously wrong. Especially if they already don’t like you anyway. It's not an entirely unreasonable instinct — I’ve probably been guilty of it myself at times. They also weren’t crazy to develop the impression that I was highly skeptical of what was being claimed about the imminence of an invasion, notwithstanding the many caveats I tried to append.

I’m not sure what the solution is. It can’t be to declare that Joe Biden is Nostradamus, or that everyone should now get together and sing kumbaya with anonymous US intelligence officials. And it can’t be that the over-eager war provocations rampant in US media are suddenly just swell. Whatever else happens with Ukraine, a presumption of incredulity toward these government/media factions still has to remain broadly in place — albeit with new Russia-specific adjustments given the crazed actions of Putin. I’ll have more to say soon on a substantive level about the nightmare that’s unfolding, including the culpability of US policy and political culture in setting the stage for this insane attack. Because it’s more vital than ever to not be cowed into ignoring the typically disastrous role of US intervention. But first I thought I owed at least a partial accounting of my own record. Consider it a work in progress.

My brain has never been particularly good at distinguishing Tracey from the similarly-named Matt Taibbi, but this is fine, Taibbi did the same thing.

War Nerd: F

I was going to make this a C or D for technically only criticizing the predictions of specific dates (the specific dates were indeed wrong). But this pushed me over the edge:

Once you’re writing songs making fun of other Ukraine predictors it’s less of a forecasting failure and more “something is seriously wrong with you”. Let’s stay with F.

Other Pundits

You can find a good list of other pundits who did poorly here, eg:

There’s a discussion of who in China was right vs. wrong here; I haven’t focused on it since I don’t recognize any of the Chinese people involved, but my takeaway is that the government seemed genuinely wrong. They weren’t just covering for Putin; they were actually taken by surprise.

My very quick search didn’t find any pundit who successfully predicted both the Russian invasion and the strong Ukranian resistance. I couldn’t even really find anybody who predicted one correctly and was silent on the other (I think Clay Graubard of Global Guessing managed this, but he’s a superforecaster, not a pundit). If you know someone in this category, please let me know so I can give them an appropriate amount of glory.

General Thoughts

Most of the people who failed badly here failed based on their political precommitments.

A bunch of leftists - Michael Tracey, Matt Taibbi, Glenn Greenwald - failed because they couldn’t believe that warmongering intelligence officials trying to scare everyone about Russia had a point. They admittedly had great heuristics: there are lots of warmongers, our intelligence community has been really wrong lots of times before, and the past few years have seen a lot of really embarrassing Russia-related paranoia. Unfortunately, the relevant Less Wrong post here is Reversed Stupidity Is Not Intelligence, and the relevant ACX post is Heuristics That Almost Always Work, so they failed.

(Can we do better than this level of agnosticism? Someone suggested that the intelligence community might suck at the sort of small-state terrorism work it’s been asked to do the past few decades, but that “infiltrating Russia” is kind of its bread and butter and a big part of its institutional DNA. Maybe we should trust it more on Great Power conflict than on tinpot dictator stuff? Maybe the other relevant ACX post here is Bounded Distrust?)

Hanania and Karlin, the two people who really succeeded at calling the invasion, were both kind of right-wing culture warriors who had political reasons to think Russia Strong and Western Culture Weak. I think this gave them an advantage in expecting Putin to act (maybe you could even frame this as “they were thinking along the same lines Putin was”?), but then gave them a disadvantage in predicting Ukrainian resistance.

One important thing I’ve learned again and again about prediction is that successes are usually less about being smart, and more about having a bias which luckily corresponds to whatever ends up happening. Lots of people failed based on their political precommittments, but I suspect the successes were also based on political precommitments. The US military-security complex and centrist establishment come out of this looking pretty good (in theory - in practice I can’t think of any of their representatives who actually made confident correct predictions). Partly this might be because they’re genuinely smart (it seems like they had real intel on what Russia was doing). But partly it’s because the truth happened to match their precommitments. They’re pro-war (or at least pro-being-concerned-about-war), so they beat the drums of “war’s going to come”, and then it came, and they looked smart. And they’re pro proxy war (or at least pro-cheering-on-our-allies), so they cheered on Ukraine, and then Ukraine did well, and they looked smart.

Thanks to the 2022 ACX Predictions Contest, I will eventually have data about all of your Ukraine-related predictions which will include demographic factors like your political beliefs. Once I get a chance to analyze that I might be able to make some of these points more forcefully.

Share this post