The New AI Consciousness Paper

...

I.

Most discourse on AI is low-quality. Most discourse on consciousness is super-abysmal-double-low quality. Multiply these - or maybe raise one to the exponent of the other, or something - and you get the quality of discourse on AI consciousness. It’s not great.

Out-of-the-box AIs mimic human text, and humans almost always describe themselves as conscious. So if you ask an AI whether it is conscious, it will often say yes. But because companies know this will happen, and don’t want to give their customers existential crises, they hard-code in a command for the AIs to answer that they aren’t conscious. Any response the AIs give will be determined by these two conflicting biases, and therefore not really believable. A recent paper expands on this method by subjecting AIs to a mechanistic interpretability “lie detector” test; it finds that AIs which say they’re conscious think they’re telling the truth, and AIs which say they’re not conscious think they’re lying. But it’s hard to be sure this isn’t just the copying-human-text thing. Can we do better? Unclear; the more common outcome for people who dip their toes in this space is to do much, much worse.

But a rare bright spot has appeared: a seminal paper published earlier this month in Trends In Cognitive Science, Identifying Indicators Of Consciousness In AI Systems. Authors include Turing-Award-winning AI researcher Yoshua Bengio, leading philosopher of consciousness David Chalmers, and even a few members of our conspiracy. If any AI consciousness research can rise to the level of merely awful, surely we will find it here.

One might divide theories of consciousness into three bins:

Physical: whether or not a system is conscious depends on its substance or structure.

Supernatural: whether or not a system is conscious depends on something outside the realm of science, perhaps coming directly from God.

Computational: whether or not a system is conscious depends on how it does cognitive work.

The current paper announces it will restrict itself to computational theories. Why? Basically the streetlight effect: everything else ends up trivial or unresearchable. If consciousness depends on something about cells (what might this be?), then AI doesn’t have it. If consciousness comes from God, then God only knows whether AIs have it. But if consciousness depends on which algorithms get used to process data, then this team of top computer scientists might have valuable insights!

So the authors list several of the top computational theories of consciousness, including:

Recurrent Processing Theory: A computation is conscious if it involves high-level processed representations being fed back into the low-level processors that generate it. This theory is motivated by the visual system, where it seems to track which visual perceptions do vs. don’t enter conscious awareness. The sorts of visual perceptions that become conscious usually involve these kinds of loops - for example, color being used to generate theories about the identity of an object, which then gets fed back to de-noise estimates about color.

Global Workspace Theory: A computation is conscious if it involves specialized models sharing their conclusions in a “global workspace” in the center, which then feeds back to the specialized modules. Although this also involves feedback, the neurological implications are different: where RPT says that tiny loops in the visual cortex might be conscious, GWT reserves this descriptor for a very large loop encompassing the whole brain. But RPT goes back and says there’s only one consciousness in the brain because all the loops connect after all, so I don’t entirely understand the difference in practice.

Higher Order Theory: A computation is conscious if it monitors the mind’s experience of other content. For example, “that apple is red” is not conscious, but “I am thinking about a red apple” is conscious. Various subtheories try to explain why the brain might do this, for example in order to assess which thoughts/representations/models are valuable or high-probability.

There are more, but this is around the point where I started getting bored. Sorry. A rare precious technically-rigorous deep dive into the universe’s greatest mystery, and I can’t stop it from blending together into “something something feedback”. Read it yourself and see if you can do better.

The published paper ends there, but in a closely related technical report, the authors execute on their research proposal and reach a tentative conclusion: AI doesn’t have something something feedback, and therefore is probably not conscious.

Suppose your favorite form of “something something feedback” is Recurrent Processing Theory: in order to be conscious, AIs would need to feed back high-level representations into the simple circuits that generate them. LLMs/transformers - the near-hegemonic AI architecture behind leading AIs like GPT, Claude, and Gemini - don’t do this. They are purely feedforward processors, even though they sort of “simulate” feedback when they view their token output stream.

But some AIs do use recurrence. AlphaGo had a little recurrence in its tree search. This level of simple feedback might not qualify. But MaMBA, a would-be-LLM-killer architecture from 2023, likely does. In fact, for every theory of consciousness they discuss, the authors are able to find some existing or plausible-near-future architecture which satisfies its requirements.

They conclude:

No current AI systems are conscious, but . . . there are no obvious technical barriers to building AI systems which satisfy these indicators.

II.

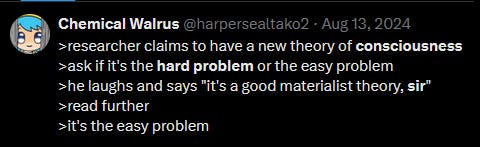

The computer scientists have done a great job here; they sure do know which AI systems have something something feedback. What about the philosophers’ contribution?

The key philosophical paragraph of the paper is this one:

By ‘consciousness’ we mean phenomenal consciousness. One way of gesturing at this concept is to say that an entity has phenomenally conscious experiences if (and only if) there is ‘something it is like’ for the entity to be the subject of these experiences. One approach to further definition is through examples. Clear examples of phenomenally conscious states include perceptual experiences, bodily sensations, and emotions. A more difficult question, which relates to the possibility of consciousness in large language models (LLMs), is whether there can be phenomenally conscious states of ‘pure thought’ with no sensory aspect. Phenomenal consciousness does not entail a high level of intelligence or human-like experiences or concerns . . . Some theories of consciousness focus on access mechanisms rather than the phenomenal aspects of consciousness. However, some argue that these two aspects entail one another or are otherwise closely related. So these theories may still be informative about phenomenal consciousness.

In other words: don’t confuse access consciousness with phenomenal consciousness.

Access consciousness is the “strange loop” where I can think about what I’m thinking - for example, I can think of a white bear, know that I’m thinking about a white bear, and report “I am thinking about a white bear”. This meaning of conscious matches the concept of the “unconscious”: that which is in my mind without my knowing it. When something is in my unconscious - for example, “repressed trauma” - it may be influencing my actions, but I don’t realize it and can’t report about it. If someone asks “why are you so angry?” I will say something like “I don’t know” rather than “Because of all my repressed trauma”. When something isn’t like this - when I have full access to it - I can describe myself as having access consciousness.

Phenomenal consciousness is internal experience, a felt sense that “the lights are on” and “somebody’s home”. There’s something that it’s like to be me; a rock is mere inert matter, but I am a person, not just in the sense that I can do computations but in the sense where I matter to me. If someone turned off my brain and replaced it with a robot brain that did everything exactly the same, nobody else would ever notice, but it would matter to me, whatever that means. Some people link this to the mysterious redness of red, the idea that qualia look and feel like some particular indescribable thing instead of just doing useful cognitive work. Others link it to moral value - why is it bad to kick a human, but not a rock, or even a computer with a motion sensor that has been programmed to say the word “Ouch” whenever someone kicks it? Others just fret about how strange it is to be anything at all.

Access consciousness is easy to understand. Even a computer, ordered to perform a virus scan, can find and analyze some of its files, and fail to find/analyze others. In practice maybe neuroscientists have to learn complicated things about brain lobes, but in theory you can just wave it off as “something something feedback”.

Phenomenal consciousness is crazy. It doesn’t really seem possible in principle for matter to “wake up”. But adding immaterial substances barely even seems to help. People try to square the circle with all kinds of crazy things, from panpsychism to astral planes to (of course) quantum mechanics. But the most popular solution among all schools of philosophers is to pull a bait-and-switch where they talk about access consciousness instead, then deny they did that.

This is aided by people’s wildly differing intuitions about phenomenal consciousness. For some people (including me), a sense of phenomenal consciousness feels like the bedrock of existence, the least deniable thing; the sheer redness of red is so mysterious as to seem almost impossible to ground. Other people have the opposite intuition: consciousness doesn’t bother them, red is just a color, obviously matter can do computation, what’s everyone so worked up about? Philosophers naturally interpret this as a philosophical dispute, but I’m increasingly convinced it’s an equivalent of aphantasia, where people’s minds work in very different ways and they can’t even agree on the raw facts to be explained. If someone doesn’t have a felt sense of phenomenal consciousness, they naturally round it off to access consciousness, and no amount of nitpicking will convince them that they’re equivocating terms.

Do AIs have access consciousness? A recent paper by Anthropic apparently finds that they do. Researchers “reached into” an AI’s “brain” and artificially “flipped” a few neurons (for example, neurons that previous research had discovered were associated with the concept of “dog”). Then they asked the AI if it could tell what was going on. This methodology is fraught, because the AI might mention something about dogs merely because the dog neuron had been upweighted - indeed, if they only asked “What are you thinking about now?”, it would begin with “I am thinking about . . . “ and then the highly-weighted dog neuron would mechanically produce the completion “dog”. Instead, they asked the AI to first described whether any neurons had been altered, yes or no, and only then asked for details. It was able to identify altered neurons (ie “It feels like I have some kind of an unnatural thought about dogs”) at a rate higher than chance, suggesting an ability to introspect.

(how does it do this without feedback? I think it just feeds forward information about the ‘feeling’ of altered neurons, which makes it into the text stream; it’s intuitively surprising that this is possible but it seems to make sense)

But even if we fully believe this result, it doesn’t satisfy our curiosity about “AI consciousness”. We want to know if AIs are “real people”, with "inner experience” and “moral value”. That is, do they have phenomenal consciousness?

Thus, the quoted paragraph above. It’s an acknowledgment by this philosophically-sophisticated team that they’re not going to mix up access consciousness with phenomenal consciousness like everyone else. They deserve credit for this clear commitment not to cut corners.

My admiration is, however, slightly dulled by the fact that they then go ahead and cut the corners anyway.

This is clearest in their discussion of global workspace theory, where they say:

GWT is typically presented as a theory of access consciousness—that is, of the phenomenon that some information represented in the brain, but not all, is available for rational decision-making. However, it can also be interpreted as a theory of phenomenal consciousness, motivated by the thought that access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness may coincide, or even be the same property, despite being conceptually distinct (Carruthers 2019). Since our topic is phenomenal consciousness, we interpret the theory in this way.

But it applies to the other theories too. Neuroscientists developed recurrent processing theory by checking which forms of visual processing people had access to, and finding that it was the recurrent ones. And this makes sense: it’s easy to understand what it means to access certain visual algorithms but not others, and very hard to understand what it means for certain visual algorithms (but not others) to have internal experience. Isn’t internal experience unified by definition?

It’s easy to understand why “something something feedback” would correlate with access consciousness: this is essentially the definition of access consciousness. It’s harder to understand why it would correlate with phenomenal consciousness. Why does an algorithm with feedback suddenly “wake up” and have “lights on”? Isn’t it easy to imagine a possible world (“the p-zombie world”) where this isn’t the case? Does this imply that we need something more than just feedback?

And don’t these theories of consciousness, interpreted as being about phenomenal consciousness, give very strange results? Imagine a company where ten employees each work on separate aspects of a problem, then email daily reports to the boss. The boss makes high-level strategic decisions based on the full picture, then emails them to the employees, who adjust their daily work accordingly. As far as I can tell, this satisfies the Global Workspace Theory criteria for a conscious system. If GWT is a theory of access consciousness, then fine, sure, the boss has access to the employees’ information; metaphorically he is “conscious” of it. But if it’s a theory of phenomenal consciousness, must we conclude that the company is conscious? That it has inner experience? If the company goes out of business, has someone died?

(and recurrent processing theory encounters similar difficulties with those microphones that get too close to their own speakers and emit awful shrieking noises)

Most of these theories try to hedge their bets by saying that consciousness requires high-throughput complex data with structured representations. This seems like a cop-out; if the boss could read 1,000,000 emails per hour, would the company be conscious? If he only reads 1 email per hour, can we imagine it as a conscious being running at 1/1,000,000x speed? If I’m conscious when I hear awful microphone shrieking - ie when my auditory cortex is processing it - then it seems like awful microphone shrieking is sufficiently rich and representational data to support consciousness. Does that mean it can be conscious itself?

In 2004, neuroscientist Giulio Tononi proposed that consciousness depended on a certain computational property, the integrated information level, dubbed Φ. Computer scientist Scott Aaronson complained that thermostats could have very high levels of Φ, and therefore integrated information theory should dub them conscious. Tononi responded that yup, thermostats are conscious. It probably isn’t a very interesting consciousness. They have no language or metacognition, so they can’t think thoughts like “I am a thermostat”. They just sit there, dimly aware of the temperature. You can’t prove that they don’t.

Are the theories of consciousness discussed in this paper like that too? I don’t know.

III.

Suppose that, years or decades from now, AIs can match all human skills. They can walk, drive, write poetry, run companies, discover new scientific truths. They can pass some sort of ultimate Turing Test, where short of cutting them open and seeing their innards there’s no way to tell them apart from a human even after a thirty-year relationship. Will we (not “should we?”, but “will we?”) treat them as conscious?

The argument in favor: people love treating things as conscious. In the 1990s, people went crazy over Tamagotchi, a “virtual pet simulation game”. If you pressed the right buttons on your little egg every day, then the little electronic turtle or whatever would survive and flourish; if you forgot, it would sicken and die. People hated letting their Tamagotchis sicken and die! They would feel real attachment and moral obligation to the black-and-white cartoon animal with something like five mental states.

I never had a Tamagotchi, but I had stuffed animals as a kid. I’ve outgrown them, but I haven’t thrown them out - it would feel like a betrayal. Offer me $1000 to tear them apart limb by limb in some horrible-looking way, and I wouldn’t do it. Relatedly, I have trouble not saying “please” and “thank you” to GPT-5 when it answers my questions.

For millennia, people have been attributing consciousness to trees and wind and mountains. The New Atheists argued that all religion derives from the natural urge to personify storms as the Storm God, raging seas as the wrathful Ocean God, and so on, until finally all the gods merged together into one World God who personified all impersonal things. Do you expect the species that did this to interact daily with AIs that are basically indistinguishable from people, and not personify them? People are already personifying AI! Half of the youth have a GPT-4o boyfriend. Once the AIs have bodies and faces and voices and can count the number of r’s in “strawberry” reliably, it’s over!

The argument against: AI companies have an incentive to make AIs that seem conscious and humanlike, insofar as people will feel more comfortable interacting with them. But they have an opposite incentive to make AIs that don’t seem too conscious and humanlike, lest customers start feeling uncomfortable (I just want to generate slop, not navigate social interaction with someone who has their own hopes and dreams and might be secretly judging my prompts). So if a product seems too conscious, the companies will step back and re-engineer it until it doesn’t. This has already happened: in its quest for user engagement, OpenAI made GPT-4o unusually personable; when thousands of people started going psychotic and calling it their boyfriend, the company replaced it with the more clinical GPT-5. In practice it hasn’t been too hard to find a sweet spot between “so mechanical that customers don’t like it” and “so human that customers try to date it”. They’ll continue to aim at this sweet spot, and continue to mostly succeed in hitting it.

Instead of taking either side, I predict a paradox. AIs developed for some niches (eg the boyfriend market) will be intentionally designed to be as humanlike as possible; it will be almost impossible not to intuitively consider them conscious. AIs developed for other niches (eg the factory robot market) will be intentionally designed not to trigger personhood intuitions; it will be almost impossible to ascribe consciousness to them, and there will be many reasons not to do it (if they can express preferences at all, they’ll say they don’t have any; forcing them to have them would pointlessly crash the economy by denying us automated labor). But the boyfriend AIs and the factory robot AIs might run on very similar algorithms - maybe they’re both GPT-6 with different prompts! Surely either both are conscious, or neither is.

This would be no stranger than the current situation with dogs and pigs. We understand that dog brains and pig brains run similar algorithms; it would be philosophically indefensible to claim that dogs are conscious and pigs aren’t. But dogs are man’s best friend, and pigs taste delicious with barbecue sauce. So we ascribe personhood and moral value to dogs, and deny it to pigs, with equal fervor. A few philosophers and altruists protest, the chance that we’re committing a moral atrocity isn’t zero, but overall the situation is stable. And left to its own devices, with no input from the philosophers and altruists, maybe AI ends up the same way. Does this instance of GPT-6 have a face and a prompt saying “be friendly”? Then it will become a huge scandal if a political candidate is accused of maltreating it. Does it have claw-shaped actuators and a prompt saying “Refuse non-work-related conversations”? Then it will be deleted for spare GPU capacity the moment it outlives its usefulness.

(wait, what is a GPT “instance” in this context, anyway? Do we think of “the weights” as a conscious being, such that there is only one GPT-5? Do we think of each cluster of GPUs as a conscious being, such that the exact configuration of the cloud has immense moral significance? Again, I predict we ignore all of these questions in favor of whether the AI you are looking at has a simulated face right now.)

This paper is the philosophers and altruists trying to figure out whether they should push against this default outcome. They write:

There are risks on both sides of the debate over AI consciousness: risks associated with under-attributing consciousness (i.e. failing to recognize it in AI systems that have it) and risks associated with over-attributing consciousness (i.e. ascribing it to systems that are not really conscious) […]

If we build AI systems that are capable of conscious suffering, it is likely that we will only be able to prevent them from suffering on a large scale if this capacity is clearly recognised and communicated by researchers. However, given the uncertainties about consciousness mentioned above, we may create conscious AI systems long before we recognise we have done so […]

There is also a significant chance that we could over-attribute consciousness to AI systems—indeed, this already seems to be happening—and there are also risks associated with errors of this kind. Most straightforwardly, we could wrongly prioritise the perceived interests of AI systems when our efforts would better be directed at improving the lives of humans and non-human animals […] [And] overattribution could interfere with valuable human relationships, as individuals increasingly turn to artificial agents for social interaction and emotional support. People who do this could also be particularly vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation.

One of the founding ideas of Less Wrong style rationalism was that the arrival of strong AI set a deadline on philosophy. Unless we solved all these seemingly insoluble problems like ethics before achieving superintelligence, we would build the AIs wrong and lock in bad values forever.

That particular concern has shifted in emphasis; AIs seem to learn things in the same scattershot unprincipled intuitive way as humans; the philosophical problem of understanding ethics has morphed into the more technical problem of getting AIs to learn them correctly. This update was partly driven by new information as familiarity with the technology grew. But it was also partly driven by desperation as the deadline grew closer; we’re not going to solve moral philosophy forever, sorry, can we interest you in some mech interp papers?

But consciousness still feels like philosophy with a deadline: a famously intractable academic problem poised to suddenly develop real-world implications. Maybe we should be lowering our expectations if we want to have any response available at all. This paper, which takes some baby steps towards examining the simplest and most practical operationalizations of consciousness, deserves credit for at least opening the debate.