The Low-Hanging Fruit Argument: Models And Predictions

...

A followup to Contra Hoel On Aristocratic Tutoring:

Imagine scientists venturing off in some research direction. At the dawn of history, they don’t need to venture very far before discovering a new truth. As time goes on, they need to go further and further.

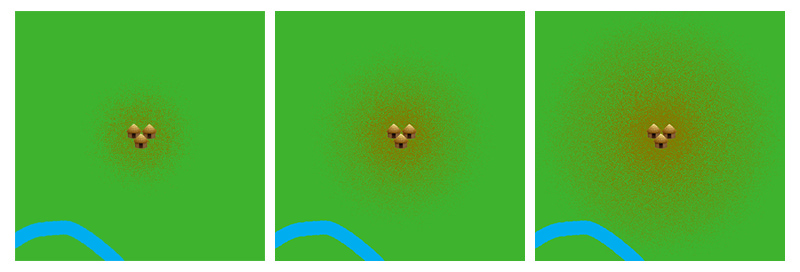

Actually, scratch that, nobody has good intuitions for truth-space. Imagine some foragers who have just set up a new camp. The first day, they forage in the immediate vicinity of the camp, leaving the ground bare. The next day, they go a little further, and so on. There’s no point in traveling miles and miles away when there are still tasty roots and grubs nearby. But as time goes on, the radius of denuded ground will get wider and wider. Eventually, the foragers will have to embark on long expeditions with skilled guides just to make it to the nearest productive land.

Let’s add intelligence to this model. Imagine there are fruit trees scattered around, and especially tall people can pick fruits that shorter people can’t reach. If you are the first person ever to be seven feet tall, then even if the usual foraging horizon is very far from camp, you can forage very close to camp, picking the seven-foot-high-up fruits that no previous forager could get. So there are actually many different horizons: a distant horizon for ordinary-height people, a nearer horizon for tallish people, and a horizon so close as to be almost irrelevant for giants.

Finally, let’s add the human lifespan. At night, the wolves come out and eat anyone who hasn’t returned to camp. So the the maximum distance anyone will ever be able to forage is a day’s walk from camp (technically half a day, so I guess let’s imagine that everyone can teleport back to camp whenever they want).

This model can explain some otherwise confusing observations about the history of science:

Early scientists should make more (and larger) discoveries than later scientists.

Early scientists should be relatively more likely to be amateurs; later scientists, professionals.

Early scientists should make discoveries younger (on average) than later scientists.

These trends should move more slowly for the most brilliant scientists.

These trends should fail to apply in fields of science that were impossible for previous generations to practice.

Going one-by-one:

1: Early scientists should make more (and larger) discoveries than later scientists

In our model, a forager spends her day walking some distance away from camp, then foraging there. Her success depends on how far from camp she is, and how depleted the food supply is in the area she tries to exploit. For example, if she has twelve hours of daylight, she might walk for six hours, then spend six hours foraging.

The very first forager can walk zero hours, then forage a 100% virgin terrain. Suppose this is worth 100 points per hour, and she spends all twelve hours foraging. She can get 1200 points.

Suppose that as time goes on, areas immediately outside camp are 100% depleted, areas 6 hours from camp are 50% depleted, and so on. A forager might choose to walk 6 hours from camp and spend the next six hours foraging in 50% depleted terrain, for 300 points. Or they might walk 9 hours from camp and forage in 25% depleted terrain for three hours, for 225 points. Since a rational forager would never choose the latter, I assume there’s some law that governs how depleted terrain would be in this scenario, which I’m violating. I can’t immediately figure out how to calculate it, so let’s just assume some foragers aren’t rational.

The point is: early foragers and later foragers both face an explore/exploit tradeoff, but that tradeoff is much better for early foragers than later ones (and trivial for the first forager, who gets no value from exploration).

Breaking out of the analogy: a scientist can spend her lifespan either catching up to the frontier of knowledge, or trying to make new discoveries (realistically these aren’t completely separate activities, but I’m modeling them as if they are). The further a scientist goes into previously unexplored sub-sub-fields, the more likely she is to reach an area nobody has ever thought about before, where there might be interesting discoveries to make. If she sticks to well-covered territory like tenth-grade Euclidean geometry, it’s very unlikely (though still not literally impossible) for her to find something everyone else has missed.

2: Early scientists should be relatively more likely to be amateurs; later scientists, professionals.

Imagine two foragers. One is a weaver, and mostly spends her time in camp weaving, but occasionally ventures out for a few hours to gather. The other is a full-time forager and spends her entire day trekking in search of food. Which is more likely to make a major find - say, a giant nest of delicious ostrich eggs, left all alone?

Just after they move camp, their relative likelihood is close to the relevant amount of time they spend foraging. If the weaver spends 2 hours a day and the professional forager spends 12 hours, it’s 1:6.

After they’ve been encamped a while and the immediate environs are depleted, it becomes much higher. Suppose the area around camp is 99% depleted, but the area three hours away is only 50% depleted. The weaver who spends two hours near camp will only get 2 points. But the professional forager who spends three hours traveling, then nine hours foraging, will get 450 points. The ratio is now 1: 225. The weaver can’t spend three hours getting to more promising terrain because she only has two hours total!

In the early days of science, many discoveries were made by lucky amateurs. Van Leeuwanhoek was a businessman; Lavoisier was an aristocrat and politician, Bayes was a minister, Franklin was a printer/author/inventor/socialite/ambassador/postmaster/firefighter/musician/philanthropist/Founding Father. Nowadays there are very occasional discoveries by amateurs (eg de Grey on chromatic number) but they seem much less frequent.

3: Early scientists should make discoveries younger (on average) than later scientists

Just after setting up camp, a forager might walk for a few minutes and stumble across the ostrich eggs. After many days of foraging, they might have to walk six hours before reaching terrain pristine enough to potentially hold such an exciting find.

Likewise, scientists should have to spend more time reaching the frontiers of knowledge before making great discoveries. According to Jones and Weinberg:

At what age do scientists tend to produce great ideas? Focusing on great scientific achievements of the 20th century, this article shows that the age–creativity relationship demonstrates much greater variation over time than across fields. Moreover, field-specific dynamics in the age–creativity relationship are closely associated with variation in other field-specific characteristics, including the prevalence of theoretical contributions, educational duration, and citation patterns. These dynamics were especially pronounced in physics during the 1920s and 1930s, when quantum mechanics was developing. Thus, although the iconic image of the young, great mind making critical breakthroughs was a good description of physics at that time, it turns out to be a poor descriptor of age–creativity patterns more generally or even of physics today, where the mean age of Nobel Prize winning achievements since 1980 is 48 y.

This is generally considered to be a function of science politics, where you need a strong career network and good connections to run your own lab, and without your own lab credit for your accomplishments will go to your mentor. I haven’t done the work you would need to distinguish between these two explanations yet, although I find it suggestive that the trend is more pronounced in theoretical physics than in biology. I’ll discuss some other ways we could test this later.

4: These trends should move more slowly for the most brilliant scientists.

Brilliant scientists might have two advantages over their slower peers, for different definitions of brilliant.

First, they could be faster learners, able to reach the frontier more quickly.

Second, they could be able to see subtle patterns other people had missed even in well-traversed ground.

This means they don’t have to waste a lot of their time reaching the frontier, and they should be able to extract value out of even “depleted” ground as if it was completely new.

I don’t really know how to test these claims, especially the second. But for what it’s worth, John von Neumann was the youngest ever lecturer at the University of Berlin, and Terence Tao was the youngest ever professor at UCLA.

5: These trends should fail to apply in fields of science that were impossible for previous generations to practice.

In Contra Hoel, I talked about machine learning as feeling different from some other scientific fields: there are frequent exciting new discoveries. This shouldn’t be surprising. Physics is stagnant because Newton and Einstein already got all the cool results. But Newton and Einstein didn’t have TPUs so they couldn’t discover things about machine learning.

(imagine one of our foragers found the entrance to a previously unknown cave system, full of mushrooms, just outside camp. There would be a brief periods when the foragers exploring these caves could discover things as quickly as the very first foragers to reach the area)

This suggests another way to test some of the hypotheses above: machine learning should have a lower age of great discoveries. Is this true?

I can’t tell. When I look at people who won the top ML prizes, they seem to be older people who had a long and distinguished career in proto-ML, eg people who pioneered the theory of reinforcement learning in the 1990s. I could try to get around this, but it would feel kind of post hoc. I’d be interested in someone comparing the average age of authors on the most cited papers in various fields over time, but I’m worried that social effects would dominate: eg many of the most innovative crypto people (eg Vitalik Buterin) seem young, but that could just be a “crypto is cool among young people” thing.

I find this model interesting because it offers a purely mechanical account of trends that most people suspect are political. Some writers attribute the decline in amateur scientists to an increasingly credentialist establishment; others attribute the decline in discoveries by young people to a gerontocracy. My guess it that it’s about 75% mechanical and 25% political, but if people disproved some of this model’s testable claims they could change my mind.