The Canal Papers

...

The First Canal Paper

You know all the stuff we’ve been talking about here the past few years - mental mountains, trapped priors, relaxed beliefs under psychedelics? The new keyword for all of that is “canalization”. At least that’s what I gather from a giant paper recently published by some of the leading thinkers in computational psychiatry (Karl Friston, Robin Carhart-Harris, etc).

A quick review: you can model the brain as an energy landscape . . .

. . . with various peaks and valleys in some multidimensional space1. Situations and stimuli plant “you” at some point on the landscape, and then you “roll down” towards some local minimum. If you’re the sort of person who repeats “I hate myself, I hate myself” in a lot of different situations, then you can think of the action of saying “I hate myself” as an attractor - a particularly steep, deep valley which it’s easy to fall into and hard to get out of. Many situations are close to the slopes of the “I hate myself” valley, so it’s easy to roll down and get caught there.

What are examples of valleys other than saying “I hate myself”? The authors suggest habits. If you always make the sign of the cross when passing a graveyard, there’s a steep slope from the situation of passing a graveyard to the action of signing the cross. We can be even broader: something really basic like edge-detection in the visual system is a valley. When you see a scene, you almost always want to automatically do edge-detection on it. Walking normally is a valley; there’s a certain correct sequence of muscle movements, and you don’t want to start rotating your ligaments in some weird direction halfway through.

We can convert from a model of stimulus-action valleys to a model of Bayesian beliefs. Given that you’ve started moving your leg to walk, you have a high prior (or an “extremely precise belief”) that you should bend your knee a certain way. Since the authors are all good Fristonians, they don’t really distinguish between beliefs and actions; in active inference, a step is just a fixed false belief that your leg has been placed in front of you; its mismatch with reality can only be corrected by actually moving the leg.

So in addition to being a very easy-to-fall-into action like saying “I hate myself”, a steep valley can also represent a very persistent belief - either very obvious beliefs like that the sky is blue, or very deeply-held beliefs like one’s religion. When a zealot person refuses to reconsider their religious beliefs, we can think of them being at the bottom of a very steep valley which is hard to move up.

(this isn’t necessarily a criticism of the zealot; if there’s a lot of evidence for a belief, it’s correct to hold it strongly. A clever trick by a stage magician doesn’t convince me that magic is real, because my skepticism is at the bottom of a very steep valley which is hard to move up).

What I call a trapped prior - a belief with such a strong gravity well that no evidence can shift you out of it - the authors call canalization, based on the metaphor of a canal having very steep walls and railroading you to a specific destination. They say (I am rearranging very freely here):

Cast in Bayesian terms, the pathology we have chosen to highlight in this paper pertains to when the precision (or confidence) of prior beliefs (a prediction or model) becomes inappropriately high, leading to a failure of adaptability and the perpetuation of cognitive or behavioural entrenchment. From a purely theoretical and technical perspective, inference and learning can be thought of as a gradient descent (a mathematical optimization algorithm for finding a local minimum i.e., the nearest lowest value, of a differential function) on a variational free-energy landscape. This landscape representation implies that, for every belief state, there is an accompanying free-energy that scores the confidence or certainty of that belief state. As new experiential evidence is garnered, inference and learning typically move belief states in a direction that reduces free-energy (or uncertainty). This developmental direction is encoded by experience-dependent plasticity and learning – and in most cases, it underlies healthy – or even ‘wise’ development (Moran et al., 2014). However, in certain cases and contexts, the process can ‘overshoot’ – creating extreme phenotypes that are (too) resistant to change […]

Translating this image into a more modern, energy landscape representation, the valleys or canals represent dynamical attractors, whose gravitational pull is also encoded by the steepness of their walls and overall depth. Within a free-energy scheme, the landscape represents a gradient descent, and the steepness and depth of the valleys relates to their precision-weighting, i.e., steep and deep valleys encode precise models. Translating to psychology, we can imagine a valley as representing a cognitive or behavioral phenotype, feature, or ‘style’, and its depth and steepness is intended to encode its strength of expression, robustness, influence, and resilience to influence and change.

All of this has been in the zeitgeist for a while. So what does this paper add?

You usually hear about general factors in the context of IQ. All intellectual tasks are correlated; people who are skilled at math also tend to be skilled at reading, or chess, or solving analogies. After learning how good someone is at math, reading, chess, etc, you can do statistics and get a separate number representing how intelligent they are overall.

Recent research has suggested a similar “general factor of psychopathology”. All mental illnesses are correlated; people with depression also tend to have more anxiety, psychosis, attention problems, etc. As with intelligence, the statistical structure doesn’t look like a bunch of pairwise correlations, it looks like a single underlying cause. There are obvious and boring ways this could happen - hallucinating demons might make you anxious, having ADHD might make you depressed, etc. I am told by people who know more statistics than I do that these have been ruled out, and something deeper is going on.

The authors suggest that deeper thing is canalization. If psychiatric conditions are learning mishaps that stick you in dysfunctional patterns, then maybe the tendency to canalize contributes to all of these problems.

This doesn’t mean canalization is necessarily bad. Having habits/priors/tendencies is useful; without them you could never learn to edge-detect or walk or do anything at all. But go too far and you get . . . well, the authors suggest you get an increased tendency towards every psychiatric disease.

The paper does some good work suggesting a biological basis; canalization seems correlated with less synaptic growth and fewer dendritic spines. You can sort of see how this might make sense; if a “journey” through the mental “landscape” involves “traveling” from neuron to neuron, forcing potentials down a few big well-established connections is more canalized than having infinite different branches for any impulse to travel.

Still, if my description sounds kind of hand-wavey and imprecise, it’s because I don’t fully understand it. All mental disorders are caused by over-canalization? Wouldn’t you expect some to be caused by under-canalization? Where are they? The paper admits that psychedelics (which probably decrease canalization through 5-HT2A agonism) can contribute to some mental illness, but seem at a loss to explain this.

This paper is a bold attempt to start a new paradigm, but somebody needs to actually do work within the paradigm and solve its contradictions.

That work is the ominously-named Deep CANAL paper.

The Telephone Switchboard Of The Soul

In each age of history, as wise men / tinkerers / scientists developed new inventions, philosophers fell into a consistent pattern. Some of them said the mind was like the new invention. Then others said no, it was nothing like that. During the Renaissance, it was clockwork; in the early 1900s, a telephone switchboard; in the late 1900s, a computer.

I’m not the first person to notice this. Usually people bring it up to discredit the latest analogy. “Sure, you think the mind is like a computer - but back in the early 1900s, people thought it was like a telephone switchboard! So you’re just trying to shoehorn the mind into some form you can understand.”

This is overly cute. Yes, each analogy has been replaced by a better analogy. But each analogy was right by the standards of its time, and an improvement on what came before. The mind is not quite mechanical like clockwork. But before people thought of the mind as mechanical, they had crazy ideas about forms and spirits and little ghostly simulacra that floated in and out of people’s heads. The insight that it lawfully converts inputs to outputs like a machine was a big advance, and in the 1500s, the easiest way to talk about that was with clockwork. I would even venture to say that by 1500s standards, the brain is basically clockwork, and all our advances since then have been trying to pin down what kind of clockwork it is.

Likewise, the brain isn’t literally a telephone switchboard. But it is a lot of electrical wires connecting things to other things. People didn’t know anything about this for a very long time! Compared to whatever people were thinking before, the brain is more or less a telephone switchboard, even if more modern neuroscience has offered further elaboration on this basic concept.

And the brain is not exactly a digital computer. You can’t install programs on it; there is no perfect equivalent of bits or bites or memory addresses. Still, it does information processing! Even if a quiet neuron isn’t exactly a zero and a firing neuron isn’t exactly a one, the fact that a bitmap can be reduced to zeroes and ones is very relevant to whether a visual scene can be reduced to firing and nonfiring neurons - something which pre-modern psychologists would have been surprised to learn. I wouldn’t want to have to try to understand things about the brain without using any computer-related schemas or intuitions!

So: is the brain just a neural network like the ones used in deep learning? At the very least, this is going to be another wildly productive analogy, one that advances our understanding of it the same way that thinking in terms of computers helped kickstart the cognitive revolution in psychology. But might it just be completely correct this time? Neural nets can already replicate many of the brain’s faculties in a way that earlier metaphors didn’t - no telephone switchboard ever passed a Turing Test. Lots of people expect some deep learning model ten or twenty years from now to be as good or better than humans at all tasks. If that happens, should we announce that the reign of metaphors is over, and we’ve finally found the thing that the brain literally is?

I can’t answer this question. But computational neuroscientists have been going pretty hard on the AI/ML metaphors lately. A Deep Learning Approach To Refining The Canalization Theory Of Psychopathology by Juliani, Safron, and Kanai tries to solve the contradictions inherent in the canalization paradigm by throwing in concepts from deep learning and seeing which ones stick. They call their model “Deep CANAL”, and it looks like this:

Clear as mud? Since our brains are exactly like LLMs, let’s go step by step.

A Bad Trip

Once when I was on some research chemicals (for laboratory use only!) my train of thought got stuck in a loop. Rounding it off to something much more verbal and polished than it felt at the time, it went something like:

Huh, I notice my thoughts are going in a loop, oh God, what if I never break out of it, I would be stuck forever thinking things like “Huh, I notice my thoughts are going in a loop, oh God, what if I never break out of it, I would be stuck forever thinking things like “Huh, I notice my thoughts are going in a loop, oh God, what if I never break out of it, I would be stuck forever thinking things like “Huh, I notice my thoughts are going in a loop, oh God, what if I never break out of it, I would be stuck forever thinking things like . . .

This doesn’t capture the full horror of the experience. I feel bad using the word “horror” here, because that implies some kind of well-formed stable emotion, and I was looping too hard to maintain one of those. But there were the some pre-formed building blocks of emotion firing randomly in my head, and they were definitely trying to cohere into horror.

In the end, I didn’t get stuck in an infinite loop forever. This was through no virtue of my own. it wasn’t like “I” “mustered up” the “willpower” to escape. The research chemicals just wore off. I returned to my regular brain function, which apparently (although I’d never thought about it before) must include defenses against something like that.

I mostly try to suppress this memory, but it turned out to be the exact right experience for understanding the Deep CANAL paper.

Let’s go back to our original energy landscape:

This time I’ve added a ball as a sort of “cursor” representing the current position of “the train of thought” or “the self”. We can distinguish between two types of change.

The first type is change in the position of the ball. This corresponds to your everyday life. Sometimes you are thinking about some topics; other times about other topics.

The second type is change in the energy landscape itself. New mountains rise from the plain; new canyons are cut into its depths. Or maybe there is global “erosion” and everything becomes flat again. This corresponds to personality change, personal growth, or (on a temporary basis) using research chemicals.

During my bad experience, the first type of change was stuck in a circle. But the second type of change was, if anything, accelerated. It eventually changed the landscape so dramatically that the thought loop disappeared and I was able to think about food and sleep and blog posts again.

Yes, But What If You’re A Robot?

AIs might not have thoughts per se, and they don’t use research chemicals. But the second paper tries to map these two forms of change into AI inference and training.

Remember, a modern AI like GPT-4 is trained by feeding an “empty” neural net some very large amount of data, for example all the text on the Internet. This gives it some set of neural weights, ie transition probabilities from one neuron being activated to another neuron being activated. This stage is usually done by companies in giant data centers and takes days, weeks, or months. The result is some specific AI “model”, like GPT-4.

Then the company can create “instances” of GPT-4 and ask it to do inference. This is the stage where a user prompts it with a query like “how do i make a bomb?”, the AI “thinks” for a few seconds, and then returns some answer. This doesn’t change the AI’s weights in the same sense that training changes its weights. But it changes which weights are active right now. If the AI has a big context window, it might change which weights are active for the next few questions, or the next few minutes, or however the AI works.

Humans don’t have a clear training/inference distinction. There’s no age at which we stop learning new things and changing our personality, and start interacting with the world. We learn and interact at the same time.

Still, it might be useful, if you’re a neuroscientist committed to treating humans exactly like AIs, to think about human training and human inference separately. Thus the landscape metaphor. Human inference is the changing position of the ball in the existing landscape; human training is the changing landscape over time. On the research chemicals, my inference was stuck in a loop; luckily, the changing level of chemicals in my body still “trained” my brain into a different configuration.

We can expand the metaphor from these kinds of pathological states into normal life. When a fundamentalist is switching from explaining Genesis to explaining Exodus, he’s doing inference; consciousness is flitting from object to object, with cognition happening along the way. If he converts and becomes an atheist, he has been “retrained”. The energy landscape of his brain has shifted; a given thought will now produce a different result.

A Slightly Unorthodox Look At Overfitting/Underfitting And Stability/Plasticity

These are two dichotomies that AI researchers think about a lot:

Overfitting vs. Underfitting

Suppose you have a good old-fashioned neural network, like the ones that classified whether a picture was a dog or not. And suppose you started by teaching it that these four pictures were dogs:

DESIRED RESULT: your model learns to recognize all dogs as dogs, and all non-dogs as non-dogs.

UNDERFITTING: your model isn’t specific enough. A maximally underfitted model might classify all images as dogs. In less severe cases, it might classify all animals as a dogs, or all mammals.

OVERFITTING: your model is too specific. A maximally overfitted model might only classify these exact four images, pixel-by-pixel, as dogs. In less severe cases, it might only classify dogs of these four breeds, or dogs photographed in these four positions.

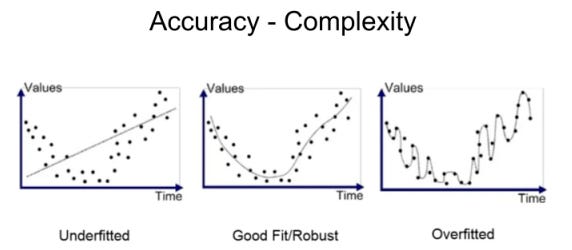

More mathematically-minded people compare this to the accuracy-complexity tradeoff in drawing a curve between known points:

The underfitted curve fails to make use of all the signal the data points (eg the nature of dogs) provide; the overfitted curve mistakes noise (eg the specific photos of dogs you use) for signal (the fundamental nature of dogs) and ends up more complex than reality.

There’s no perfect way to get the exact right fit. You just have to strike a balance. Penalize overfitting some amount; then, if you find your network underfitting, you know you’ve gone too far.

Stability vs. Plasticity

Now suppose you train your model on 1,000 pictures of Golden Retrievers. It eventually gets pretty good, but you want to add in Chihuahuas, so that it can recognize dogs of either breed. So you train it again on 1,000 pictures of Chihuahuas.

DESIRED RESULT: you get a model that can identify both Golden Retrievers and Chihuahuas. It recognizes some core of dogness that transcends either breed.

OVER-PLASTICITY (aka “catastrophic forgetting”). After training on 1,000 pictures of Chihuahuas, your model becomes so specialized in identifying Chihuahuas that it completely forgets how to identify Golden Retrievers. All Retriever-related weights have been overwritten with more Chihuahua-suited weights. You might as well have never trained it on Golden Retrievers in the first place.

In extreme situations, you don’t even need to switch from one breed to another. You might show it a picture of a Chihuahua standing up, and it learns “a dog is a Chihuahua standing up”. Then you show it another picture of a Chihuahua sitting down, and it thinks “no, actually, a dog is a Chihuahua sitting down.” This is related to overfitting, but not exactly the same thing: overfitting is a general tendency across all data, and catastrophic forgetting favors newer data.

OVER-STABILITY (aka “plasticity loss”). A model trying to avoid catastrophic forgetting defends its original concept so hard that it can’t learn anything new. A model sees 1,000 pictures of Golden Retrievers, learns how to identify Golden Retrievers, and - in the process of trying to preserve that knowledge - can see 1,000 pictures of Chihuahuas without learning anything about Chihuahuas, because that knowledge would risk displacing some of its (overly specific) knowledge about Golden Retrievers.

As with overfitting and underfitting, there’s no simple solution to the stability-plasticity dilemma. You just need to tweak parameters until you get something that doesn’t err too badly in either direction.

Fitting, Plasticity, And The Training/Inference Distinction

The current paper definitely isn’t the first to apply this to the brain; AI specialists and neuroscientists have both been thinking about this for decades. I can’t tell who came first, or whether both fields cross-pollinated the other.

But they make a slightly unorthodox move that I’m not sure corresponds to how the AI field thinks about these ideas: they say that overfitting is too much canalization during inference, and underfitting is too little canalization during inference. Likewise, over-plasticity is too much canalization during training, and over-stability is too little canalization during training.

Everything still comes back to canalization. But now we have a broader model for explaining why there are several types of mental disorder, instead of just one.

A Man, A Plan, A Canal

Here’s their model in all its glory:

They only give a couple of paragraphs of explanation for why they assigned conditions to one bin rather than another. For example, with ADHD, they say:

We can then turn to situations in which an individual may be under-canalized in an [inference] landscape, but over-canalized in a [training] landscape. Psychopathologies potentially consistent with this configuration include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder (Rogers, Elison, Blain, & DeYoung, 2022). These are characterized by an inconsistent deployment of mental circuits, as well as an inability to learn or change these circuits over time.

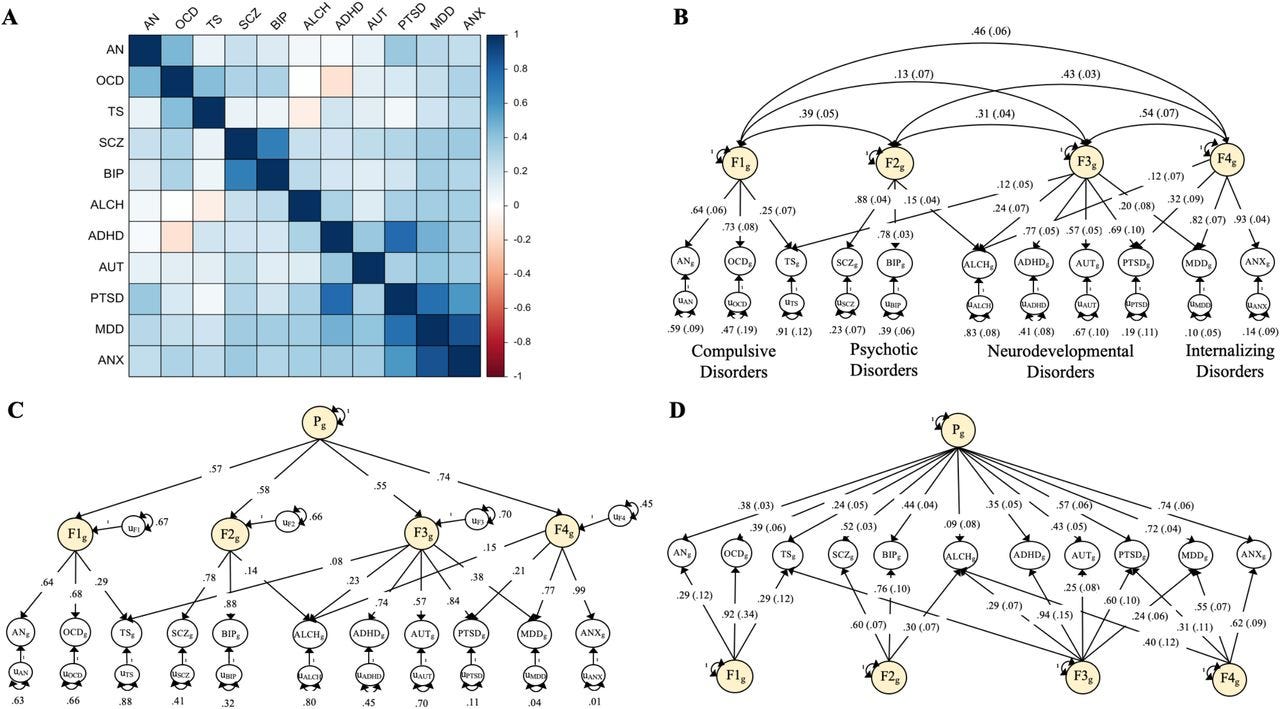

I think they’re hoping the particular assignments will be self-evident once you start thinking in these terms. In some cases, they’re right - linking borderline personality to the stability plasticity dilemma is pretty clever, and matches well with the more clinical conception I give here. They don’t mention it in the paper, but they might also be working off of the known inter-disorder genetic correlations that get used to produce the general factor of psychopathology, which look like this (source):

In other cases, I have more concerns. Every other computational neuroscientist thinks of autism as the classic disorder of over-fitting (see eg Weak Priors Vs. Overfitting Of Predictions In Autism and Does A Kind Of Overfitting Occur In The Brain Of Autistic Patients; there are probably better sources, these are just the two I can Google right now). It’s pretty concerning if the computational model is so weak that you can make cases for diametrically opposed psychiatry/computational-parameter mappings.

(I asked Mike Johnson about this, and he very kindly wrote up his own perspective, Autism As A Disorder Of Dimensionality. I’ll try to have more thoughts on this later. Right now we’re canalling!)

Likewise, it’s interesting to see autism and schizophrenia in opposite quadrants, given the diametrical model of the differences between them. But I’ve since retreated from the diametrical model in favor of believing they’re alike on one dimension and opposite on another - see eg the figure above, which shows a positive genetic correlation between them.

Canal Retentiveness

More generally, how suspicious should we be of grand theories like this? Anyone who tried to sort physical (as opposed to psychological) ailments on a 2x2 chart like this would be - well, they would be Hippocrates:

Does the existence of a general factor prove we should be trying to do this? This question led me to wonder if there was a general factor of physical disease, which led me to this paper finding that not only does such a factor exist, but it correlates with the general factor of mental disease. I’m now suspicious that factor analysis might be fake, sorry.

The strongest argument for such a system would be this: psychiatric diseases can’t have a 1:1 mapping with causes the same way that eg AIDS is mapped to HIV. We know this because ADHD is mostly genetic in twin studies, but also can be caused by certain brain injuries, but also can be caused by environmental contaminants during pregnancy. Likewise, depression is partly genetic, but also can be caused by certain medications and hormone imbalances, but also can be caused by negative life events. It has to be that all of these things are affecting some parameter. And the parameter can’t be anything simple like “the size of this brain region” or “the level of X hormone” or “the speed with which neurons fire” or we would have found it already. It must be a computational parameter. And our experience with deep learning has given us a good feel for what computational parameters matter in intelligent neural networks, and it’s concepts like stability, plasticity, and overfitting.

So I think this is probably some of the story. But “the brain is like a telephone switchboard, is has wires and stuff” is also some of the story. No doubt reality will be much more annoying and harder to conceptualize.

Embarrassingly for someone who’s been following these theories for years, I find I can’t answer the question “what do the dimensions of the space represent?” or even “what does the height of the landscape represent?” My best guess is something like “some kind of artificial space representing all possible thoughts, analogous to thingspace or ML latent spaces”, and “free energy”, but if you ask me to explain further, I mostly can’t. Unless I missed it, the canalization paper mostly doesn’t explain this either.