Slightly Against Underpopulation Worries

...

So I hear there’s an underpopulation crisis now.

I think the strong version of this claim - that underpopulation could cause human extinction - is 100% false.

The weaker version - that it could make life unpleasant in some countries - is true. But I don’t think it’s at the top of any list of things to worry about.

1: Declining Birth Rates Won’t Drive Humans Extinct, Come On

Not only are we not going to go extinct because of underpopulation, population is going to continue to rise for the next 80 years.

Although growth rate may hit zero a little after 2100, it will be centuries before the human population gets any lower than it is today - if it ever does.

This is mostly because of sub-Saharan Africa (especially Nigeria) where birth rates remain very high. Although these are going down, in some cases faster than expected, current best projections say they will stay high enough to keep population growing for the rest of the century.

2: Immigrant-Friendly Countries Will Keep Growing

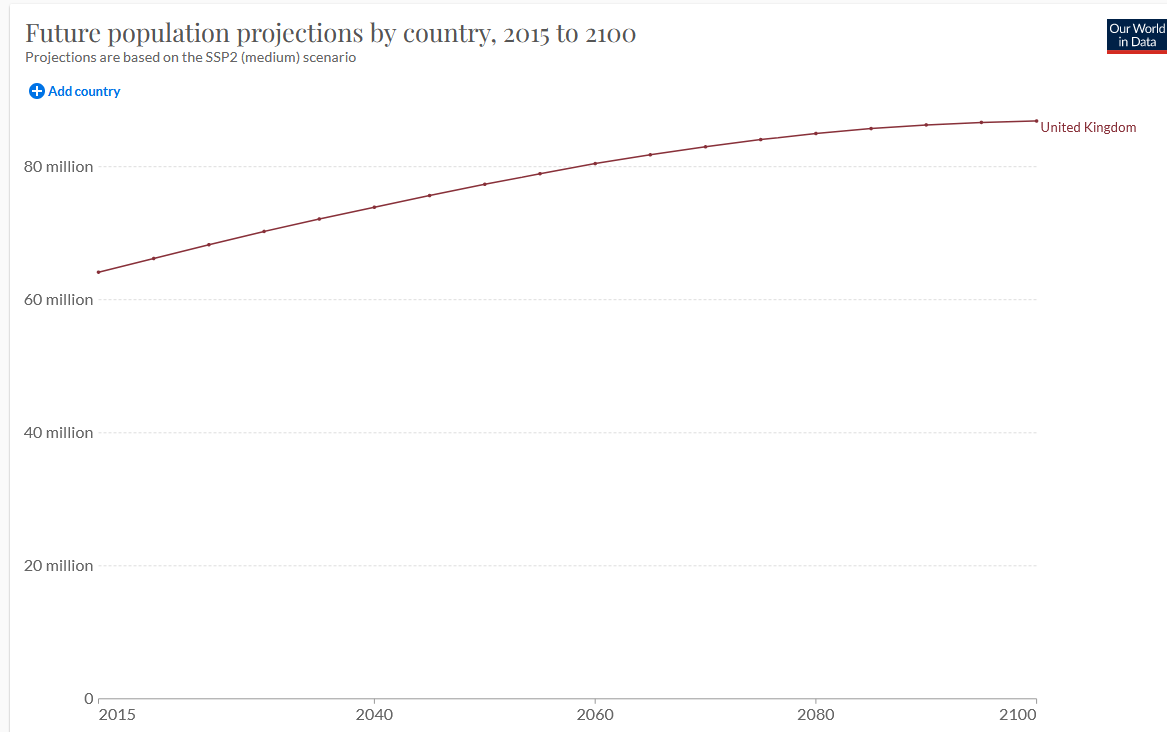

Here are Our World In Data’s projections for US and UK populations:

The US will grow from about 330 million people today to about 430 million in 2100; the UK from about 60 million to 80 million. Most of this growth will be immigration. Some of these immigrants will come from sub-Saharan Africa, others from countries whose populations are themselves declining (sorry, other countries).

3: Countries With Low Immigration Will Shrink, But Mostly Slowly

Brazil will go from 210 million today to 190 million in 2100.

Germany will go from 80 million to 70 million.

Japan will go from 125 million to 70 million.

India will go from 1.3 billion today, to a peak of 1.8 billion in 2060, before declining back to 1.6 billion in 2100.

China will go from 1.4 billion today to 800 million in 2100.

Aside from Japan and China, these are relatively gentle drops even over the course of a century.

4: Big Relative Drops Still Imply High Absolute Populations

But Japan and China will drop a lot. By 2100, there will only be 800 million Chinese and 70 million Japanese.

Still: in the early 1900s, America and Europe were gripped by fear of “the Yellow Peril”: what if innumerable hordes of Orientals overran the West using their limitless numbers? Chinese and Japanese people were likened to swarms of insects, or flocks of birds: so numerous that it was incomprehensible and almost obscene.

At the time, there were about 500 million Chinese and 50 million Japanese.

East Asia will probably be hit worst by underpopulation, with low birth rates and little immigration. But by 2100, there will still be 50% more East Asians than there were in 1920, when everyone was terrified of how many East Asians there were. Honestly, 800 million Chinese people still seems like a lot.

The same is true in the West. The number of native-born white Americans is predicted to fall from 200 million to 140 million by 2100, a 30% decrease. But 140 million native-born white Americans is about as many as there were in 1965, when native-born white American Paul Ehrlich wrote Population Bomb, claiming that current populations were unsustainable and the world would collapse soon. On the way up, people were able to look at same these numbers and see them as terrifyingly high. Is there some objective standard by which we should look at them and instead find them worryingly low?

5: Concerns About “Underpopulation” Make More Sense As Being About Demographic Shift

In high-immigration countries, declining birth rates will cause changing ethnic demographics, as native populations shrink and immigrant populations increase.

I understand why people don’t want to talk about the issue this way, because if you say demographic shift is a problem, people will call you a racist conspiracy theorist. I don’t think it’s racist to care about ethnic demographic shift - I think Japan as it currently exists is not completely interchangeable with a Japan made of 1/3 ethnic Japanese people and 2/3 ethnic Kenyans. But that’s probably not a discussion people can have openly given today’s climate. So I appreciate the reasons why people would want to say things about “underpopulation” and “human extinction” instead. But technically these things are false.

In low-immigration countries, ethnic demographics won’t shift, but age demographics will: since each generation is smaller than the last, there will be more old people than young people. See Section 6 below for more.

6. Age Pyramid Concerns Are Real, But Not Compatible With Technological Unemployment Concerns

As birth rates rise, you have many hard-working young people supporting a small number of retirees. As they fall, you have fewer young people and more older people who need support. This either burdens the young, or requires cuts in support for the elderly.

And yeah, to some degree this will happen. I think it will look less like an apocalypse and more like increasing effective retirement ages, but that will suck.

On the other hand, this is basically a complaint about a shortage of labor. And I notice it’s weird to be worried both that the future will be racked by labor shortages, and that we’ll suffer from technological unemployment and need to worry about universal basic income. You really have to choose one or the other. I’m pretty worried about technological unemployment myself.

Another way of saying “labor shortage” is “the value of labor relative to capital goes up”. Workers will be able to expect high salaries and good working conditions. Labor shortages are also periods of intense innovation for labor-saving devices (some historians blame the Industrial Revolution on unusually high wages in the England of the time).

7: Dysgenics Is Real But Pretty Slow

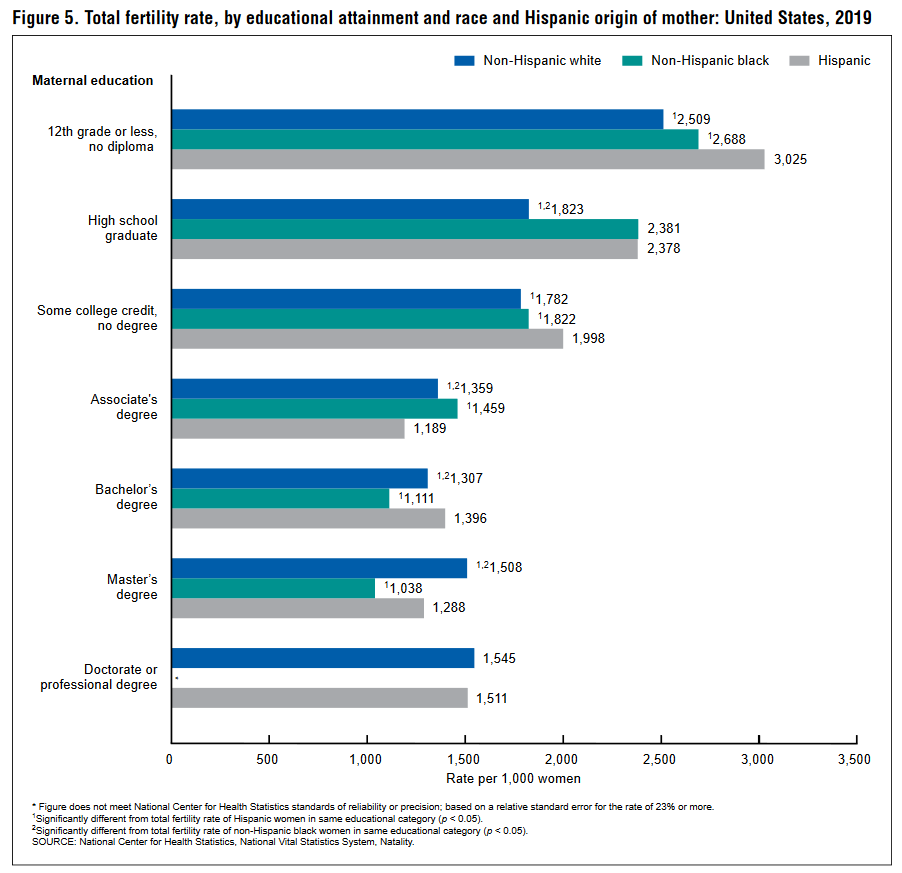

Another potential demographic shift in both types of country is shift among social classes / levels of educational attainment:

In general, educated people reproduce less than uneducated people (although this picks up slightly at the doctorate level).

The claim isn’t that fewer people will have PhDs in the future: colleges will certainly solve that by increasing access to education and/or dumbing down requirements. It’s a dysgenic argument where we assume at any given time the people with higher degrees have on average higher genetic intelligence levels. If they’re reproducing less, the genetic intelligence level of the population will decrease.

There is some debate in the scientific community about whether this is happening, but as far as I can tell the people who claim it isn’t have no good refutation for the common sense argument that it has to be. The people who claim that it is make more sense, and have measured the effect in Iceland, an isolated population that it’s easy to measure genetic effects in. It seems to be a decline of about 0.3 IQ points per decade. If the American rate is close to the Icelandic one, this implies that the average US IQ in 2100 will be 97.5 by current standards, unless we get more mileage out of the Flynn Effect, in which case it might be higher (although the environmental Flynn Effect and genetic dysgenic effects seem to hit slightly different skills). I think societies are probably hyper-sensitive to small changes in average IQ, so I’m not excited about this, but I don’t expect it to directly be apocalyptic.

8. Innovation Concerns Are Real But Probably Overwhelmed By Other Factors

The more people are innovating and researching things, the faster technology advances, and the more the economy grows (I wrote a bit about this here). As population growth slows, we should expect technological and economic growth to slow too.

But this can’t be the whole story. After all, consider the century 1820 - 1920. It gave us the steamship, the railroad, the automobile, the factory, mass production, electricity, refrigeration, radio, the airplane, etc, etc, etc, with a population only about 10 - 20% as high as today. The effective innovating population - the number of educated people living in countries on the technological frontier - was probably an even smaller proportion. About half of these innovations came from Britain, a country with about 0.3% the current world population. So the solution is clear - just give everyone the same scientific productivity as 19th century British people, and we can cut the population by a factor of 300 without consequence!

I’m joking, of course. What it actually means is that science is slowing down. I write about this phenomenon - amply described and categorized by various economists and other thinkers - here - in the context of a paper finding that the number of researchers has increased by about 10x since the early 1900s, but science seems to be moving only at the same rate, or maybe even a little slower.

(there might be an exception for fields of science that couldn’t have existed in the 19th and early 20th century - see here for more)

My current model is that there are two trends - a trend for low-hanging fruit to get picked and science to become harder over time, and a counterbalancing trend for population increases and number of researchers per X people to increase. The studies cited there suggest that you need about a 10x researcher population increase per century to compensate for the low-hanging fruit effect - or, alternately, that absent any population increases, science will go about 10x slower each century. I’m sure this number itself isn’t the full story and it’s probably way off anyway, but I think we should expect something like this to be true.

This makes me think that declining population in educated countries on the order of 30% or so isn’t that interesting in terms of innovation rate. Other factors are going to overwhelm this effect.

I guess it’s still true that if innovation is destined to be only 10% of its current level in 2100, then a 30% population decline could lower that to 7%. I find it hard to worry about such a small difference, but maybe that’s a flaw in me and not in the territory.

9. In The Short-To-Medium Run, We’re All Dead

Maybe all these arguments sound half-hearted? Like I’m conceding too much ground? Like I should still be worrying about underpopulation more than I do? Or that even if I’m right that things won’t degenerate too far by 2100, we should be thinking forward to 2200 or 2300?

Fine. My real argument is that 2100 is not a real year. You make a mistake by thinking about it at all.

The term “technological singularity” gets overused, but the original definition is “a point where things change so profoundly that it’s not worth speculating about what happens afterwards”.

If we don’t die of something else first, there will probably be a technological singularity before 2100. The way things are looking now, it will probably involve AI somehow. If by some miracle that doesn’t happen, we’ll get one involving human genetic engineering for intelligence. I think there’s maybe a 5-10% chance we somehow manage to miss both of those entirely, but I’m not spending too many of my brain cycles worrying about this weird sliver of probability space.

This is why I even though I love predictions, I couldn’t bring myself to participate in the “predict what the world will be like in 2050!” contest that was going around this part of the blogosphere recently. Even 2050 is starting not to seem like a very real year. Don’t get me wrong, I think there’s even odds it happens, I would just feel silly predicting something like “US politics will center around this set of issues” and then 2050 comes along and things are more like “the cloud of microscopic death robots that used to be our solar system has expanded as far as Sirius B”.

Even if these trends don’t reach singularity level, they probably reach “big enough that it’s not worth speculating about underpopulation” level. Like, a 2.5 point decline in IQ could be pretty bad. But if we can’t genetic engineer superbabies with arbitrary IQs by 2100, we have failed so overwhelmingly as a civilization that we deserve whatever kind of terrible discourse our idiot grandchildren inflict on us.

And are we seriously expecting First World countries to be worrying about labor shortages by 2100?

So to steal a turn of phrase from Andrew Ng, in this kind of situation, worrying about underpopulation in 2100 is like worrying about underpopulation on Mars. It’s too far in the future to be worth thinking about.

Appendix: The Amish Inversion

Suppose that there is a 2100 - and even a 2200, 2300, etc. What happens if we extend current trends?

Answer: the Amish take over the world.

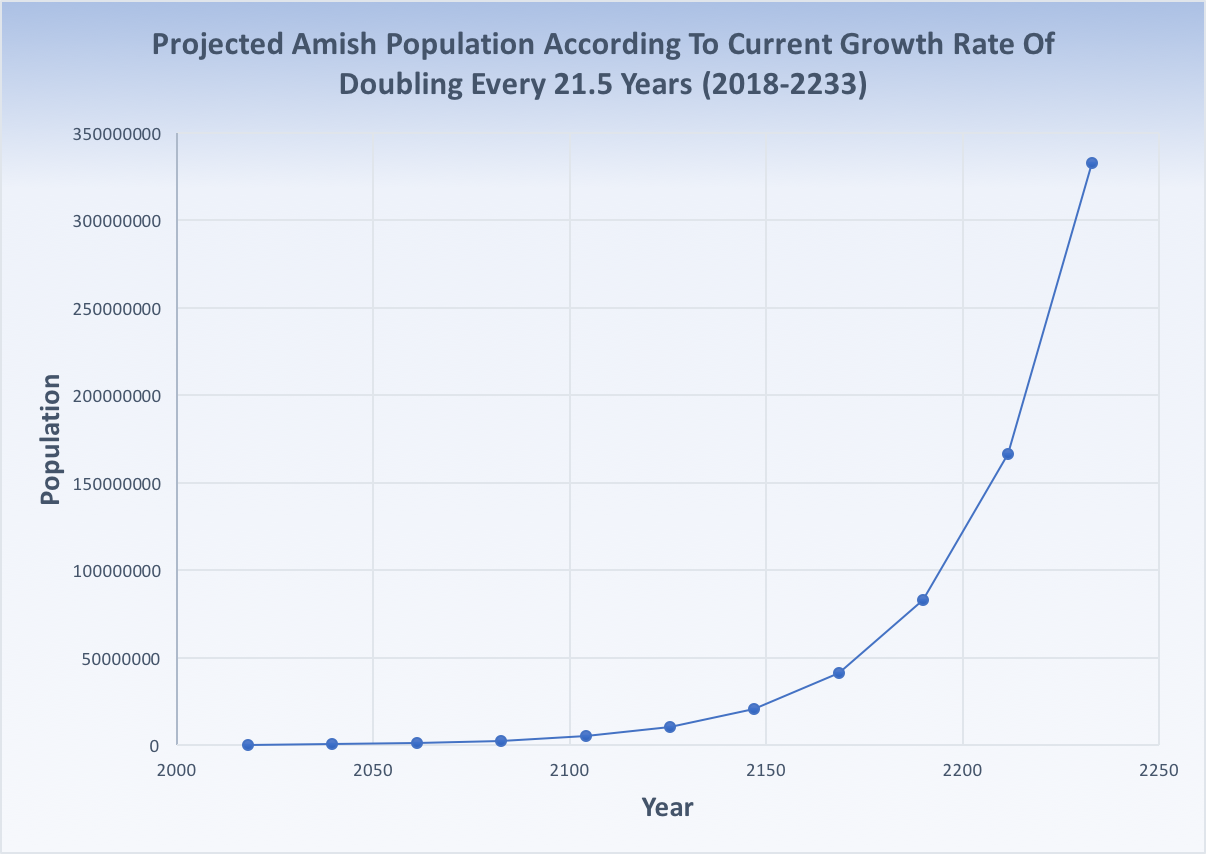

The Amish have about seven children per family. Their population doubles every twenty years. This has been very consistent; the Amish never change. Relatively few Amish “defect” to regular modern society. As regular American birth rates get lower, the percent of the American population who are Amish rises.

The Daily Caller has an article on how the Amish [Are] Projected To Overtake Current US Population In 215 Years If Growth Rates Continue. It predicts Amish-non-Amish parity around 2250:

But in fact, the Amish will not quite be a majority of Americans in 2250, because Orthodox Jews have only-slightly-slower growth rates.

Assume that regular US population stabilizes at 430 million in 2100. By 2250, the population is 430 million regulars, 450 million Amish, and 100 million Orthodox Jews, for a total of about a billion people.

Even this isn’t quite right, because a lot of Orthodox Jews do leave Orthodoxy, so along with those 100 million devout Orthodox there will probably be a few dozen million extra Reform Jews with a confused relationship to religion and lots of emotional baggage. It’ll be a great time for the rationalist community.