OpenAI's "Planning For AGI And Beyond"

...

Planning For AGI And Beyond

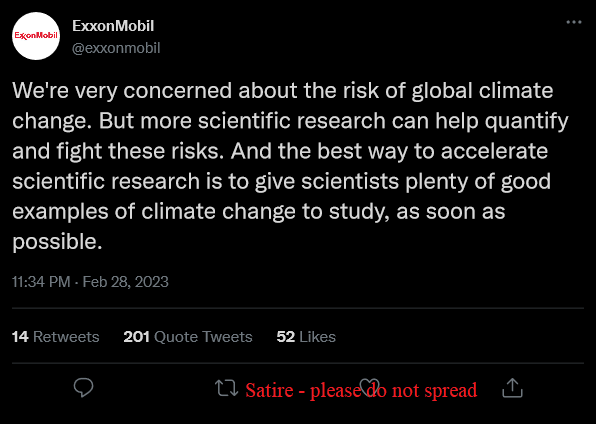

Imagine ExxonMobil releases a statement on climate change. It’s a great statement! They talk about how preventing climate change is their core value. They say that they’ve talked to all the world’s top environmental activists at length, listened to what they had to say, and plan to follow exactly the path they recommend. So (they promise) in the future, when climate change starts to be a real threat, they’ll do everything environmentalists want, in the most careful and responsible way possible. They even put in firm commitments that people can hold them to.

An environmentalist, reading this statement, might have thoughts like:

Wow, this is so nice, they didn’t have to do this.

I feel really heard right now!

They clearly did their homework, talked to leading environmentalists, and absorbed a lot of what they had to say. What a nice gesture!

And they used all the right phrases and hit all the right beats!

The commitments seem well thought out, and make this extra trustworthy.

But what’s this part about “in the future, when climate change starts to be a real threat”?

Is there really a single, easily-noticed point where climate change “becomes a threat”?

If so, are we sure that point is still in the future?

Even if it is, shouldn’t we start being careful now?

Are they just going to keep doing normal oil company stuff until that point?

Do they feel bad about having done normal oil company stuff for decades? They don’t seem to be saying anything about that.

What possible world-model leads to not feeling bad about doing normal oil company stuff in the past, not planning to stop doing normal oil company stuff in the present, but also planning to do an amazing job getting everything right at some indefinite point in the future?

Are they maybe just lying?

Even if they’re trying to be honest, will their bottom line bias them towards waiting for some final apocalyptic proof that “now climate change is a crisis”, of a sort that will never happen, so they don’t have to stop pumping oil?

This is how I feel about OpenAI’s new statement, Planning For AGI And Beyond.

OpenAI is the AI company behind ChatGPT and DALL-E. In the past, people (including me) have attacked them for seeming to deprioritize safety. Their CEO, Sam Altman, insists that safety is definitely a priority, and has recently been sending various signals to that effect.

Planning For AGI And Beyond (“AGI” = “artificial general intelligence”, ie human-level AI) is the latest volley in that campaign. It’s very good, in all the ways ExxonMobil’s hypothetical statement above was very good. If they’re trying to fool people, they’re doing a convincing job!

Still, it doesn’t apologize for doing normal AI company stuff in the past, or plan to stop doing normal AI company stuff in the present. It just says that, at some indefinite point when they decide AI is a threat, they’re going to do everything right.

This is more believable when OpenAI says it than when ExxonMobil does. There are real arguments for why an AI company might want to switch from moving fast and breaking things at time t to acting all responsible at time t + 1 . Let’s explore the arguments they make in the document, go over the reasons they’re obviously wrong, then look at the more complicated arguments they might be based off of.

Why Doomers Think OpenAI Is Bad And Should Have Slowed Research A Long Time Ago

OpenAI boosters might object: there’s a disanalogy between the global warming story above and AI capabilities research. Global warming is continuously bad: a temperature increase of 0.5 degrees C is bad, 1.0 degrees is worse, and 1.5 degrees is worse still. AI doesn’t become dangerous until some specific point. GPT-3 didn’t hurt anyone. GPT-4 probably won’t hurt anyone. So why not keep building fun chatbots like these for now, then start worrying later?

Doomers counterargue that the fun chatbots burn timeline.

That is, suppose you have some timeline for when AI becomes dangerous. For example, last year Metaculus thought human-like AI would arrive in 2040, and superintelligence around 2043.

Recent AIs have tried lying to, blackmailing, threatening, and seducing users. AI companies freely admit they can’t really control their AIs, and it seems high-priority to solve that before we get superintelligence. If you think that’s 2043, the people who work on this question (“alignment researchers”) have twenty years to learn to control AI.

Then OpenAI poured money into AI, did ground-breaking research, and advanced the state of the art. That meant that AI progress would speed up, and AI would reach the danger level faster. Now Metaculus expects superintelligence in 2031, not 2043 (although this seems kind of like an over-update), which gives alignment researchers eight years, not twenty.

So the faster companies advance AI research - even by creating fun chatbots that aren’t dangerous themselves - the harder it is for alignment researchers to solve their part of the problem in time.

This is why some AI doomers think of OpenAI as an Exxon-Mobil style villain, even though they’ve promised to change course before the danger period. Imagine an environmentalist group working on research and regulatory changes that would have solar power ready to go in 2045. Then ExxonMobil invents a new kind of super-oil that ensures that, nope, all major cities will be underwater by 2031 now. No matter how nice a statement they put out, you’d probably be pretty mad!

Why OpenAI Thinks Their Research Is Good Now, But Might Be Bad Later

OpenAI understands the argument against burning timeline. But they counterargue that having the AIs speeds up alignment research and all other forms of social adjustment to AI. If we want to prepare for superintelligence - whether solving the technical challenge of alignment, or solving the political challenges of unemployment, misinformation, etc - we can do this better when everything is happening gradually and we’ve got concrete AIs to think about:

We believe we have to continuously learn and adapt by deploying less powerful versions of the technology in order to minimize “one shot to get it right” scenarios […] As we create successively more powerful systems, we want to deploy them and gain experience with operating them in the real world. We believe this is the best way to carefully steward AGI into existence—a gradual transition to a world with AGI is better than a sudden one. We expect powerful AI to make the rate of progress in the world much faster, and we think it’s better to adjust to this incrementally.

A gradual transition gives people, policymakers, and institutions time to understand what’s happening, personally experience the benefits and downsides of these systems, adapt our economy, and to put regulation in place. It also allows for society and AI to co-evolve, and for people collectively to figure out what they want while the stakes are relatively low.

You might notice that, as written, this argument doesn’t support full-speed-ahead AI research. If you really wanted this kind of gradual release that lets society adjust to less powerful AI, you would do something like this:

Release AI #1

Wait until society has fully adapted to it, and alignment researchers have learned everything they can from it.

Then release AI #2

Wait until society has fully adapted to it, and alignment researchers have learned everything they can from it.

And so on . . .

Meanwhile, in real life, OpenAI released ChatGPT in late November, helped Microsoft launch the Bing chatbot in February, and plans to announce GPT-4 in a few months. Nobody thinks society has even partially adapted to any of these, or that alignment researchers have done more than begin to study them.

The only sense in which OpenAI supports gradualism is the sense in which they’re not doing lots of research in secret, then releasing it all at once. But there are lots of better plans than either doing that, or going full-speed-ahead.

So what’s OpenAI thinking? I haven’t asked them and I don’t know for sure, but I’ve heard enough debates around this that I have some guesses about the kinds of arguments they’re working off of. I think the longer versions would go something like this:

The Race Argument:

Bigger, better AIs will make alignment research easier. At the limit, if no AIs exist at all, then you have to do armchair speculation about what a future AI will be like and how to control it; clearly your research will go faster and work better after AIs exist. But by the same token, studying early weak AIs will be less valuable than studying later, stronger AIs. In the 1970s, alignment researchers working on industrial robot arms wouldn’t have learned anything useful. Today, alignment researchers can study how to prevent language models from saying bad words, but they can’t study how to prevent AGIs from inventing superweapons, because there aren’t any AGIs that can do that. The researchers just have to hope some of the language model insights will carry over. So all else being equal, we would prefer alignment researchers get more time to work on the later, more dangerous AIs, not the earlier, boring ones.

“The good people” (usually the people making this argument are referring to themselves) currently have the lead. They’re some amount of progress (let’s say two years) ahead of “the bad people” (usually some combination of Mark Zuckerberg and China). If they slow down for two years now, the bad people will catch up to them, and they’ll no longer be setting the pace.

So “the good people” have two years of lead, which they can burn at any time.

If the good people burn their lead now, the alignment researchers will have two extra years studying how to prevent language models from saying bad words. But if they burn their lead in 5-10 years, right before the dangerous AIs appear, the alignment researchers will have two extra years studying how to prevent advanced AGIs from making superweapons, which is more valuable. Therefore, they should burn their lead in 5-10 years instead of now. Therefore, they should keep going full speed ahead now.

The Compute Argument:

Future AIs will be scary because they’ll be smarter than us. We can probably deal with something a little smarter than us (let’s say IQ 200), but we might not be able to deal with something much smarter than us (let’s say IQ 1000).

If we have a long time to study IQ 200 AIs, that’s good for alignment research, for two reasons. First of all, these are exactly the kind of dangerous AIs that we can do good research on - figure out when they start inventing superweapons, and stamp that tendency out of them. Second, these IQ 200 AIs will probably still be mostly on our side most of the time, so maybe they can do some of the alignment research themselves.

So we want to maximize the amount of time it takes between IQ 200 AIs and IQ 1000 AIs.

If we do lots of AI research now, we’ll probably pick all the low-hanging fruit, come closer to optimal algorithms, and the limiting resource will be compute - ie how many millions of dollars you want to spend building giant computers to train AIs on. Compute grows slowly and conspicuously - if you’ve just spent $100 million on giant computers to train AI, it will take a while before you can gather $1 billion to spend on even gianter computers. Also, if terrorists or rogue AIs are gathering a billion dollars and ordering a giant computer from Nvidia, probably people will notice and stop them.

On the other hand, if we do very little AI research now, we might not pick all the low-hanging fruit, and we might miss ways to get better performance out of smaller amounts of compute. Then an IQ 200 AI could invent those ways, and quickly bootstrap up to IQ 1000 without anyone noticing.

So we should do lots of AI research now.

The Fire Alarm Argument:

Bing’s chatbot tried to blackmail its users, but nobody was harmed and everyone laughed that off. But at some point a stronger AI will do something really scary - maybe murder a few people with a drone. Then everyone will agree that AI is dangerous, there will be a concerted social and international response, and maybe something useful will happen. Maybe more of the world’s top geniuses will go into AI alignment, or will be easier to coordinate a truce between different labs where they stop racing for the lead.

It would be nice if that happened five years before misaligned superintelligences building superweapons, as opposed to five months before it, since five months might not be enough time for the concerted response to do something good.

As per the previous two arguments, maybe going faster now will lengthen the interval between the first scary thing and the extremely dangerous things we’re trying to prevent.

These three lines of reasoning argue that that burning a lot of timeline now might give us a little more timeline later. This is a good deal if:

Burning timeline now actually buys us the extra timeline later. For example, it’s only worth burning timeline to establish a lead if you can actually get the lead and keep it.

A little bit of timeline later is worth a lot of timeline now.

Everybody between now and later plays their part in this complicated timeline-burning dance and doesn’t screw it up at the last second.

I’m skeptical of all of these.

DeepMind thought they were establishing a lead in 2008, but OpenAI has caught up to them. OpenAI thought they were establishing a lead the past two years, but a few months after they came out with GPT, at least Google, Facebook, and Anthropic had comparable large language models; a few months after they came out with DALL-E, random nobody startups came out with StableDiffusion and MidJourney. None of this research has established a commanding lead, it’s just moved everyone forward together and burned timelines for no reason.

The alignment researchers I’ve talked to say they’ve already got their hands full with existing AIs. Probably they could do better work with more advanced models, but it’s not an overwhelming factor, and they would be happiest getting to really understand what’s going on now before the next generation comes out. One researcher I talked to said the arguments for acceleration made sense five years ago, when there was almost nothing worth experimenting on, but that they no longer think this is true.

Finally, all these arguments for burning timelines require that lots of things go right later. The same AI companies burning timelines now turn into model citizens when the stakes get higher, and convert their lead into improved safety instead of capitalizing on it to release lucrative products. The government responds to an AI crisis responsibly, rather than by ignoring it or making it worse.

If someone screws up the galaxy-brained plan, then we burn perfectly good timeline but get none of the benefits.

Why Cynical People Might Think All Of This Is A Sham Anyway

These are interesting arguments. But we should also consider the possibility that OpenAI is a normal corporation, does things for normal corporate reasons (like making money), and releases nice-sounding statements for normal corporate reasons (like defusing criticism).

Brian Chau has an even more cynical take:

OpenAI wants to sound exciting and innovative. If they say “we are exciting and innovative”, this is obvious self-promotion and nobody will buy it. If they say “we’re actually a dangerous and bad company, our products might achieve superintelligence and take over the world”, this makes them sound self-deprecating, while also establishing that they’re exciting and innovative.

Is this too cynical? I’m not sure. On the one hand, OpenAI has been expressing concern about safety since day one - the article announcing their founding in 2015 was titled Elon Musk Just Founded A New Company To Make Sure Artificial Intelligence Doesn’t Destroy The World.

On the other hand - man, they sure have burned a lot of timeline. The big thing all the alignment people were trying to avoid in the early 2010s was an AI race. DeepMind was the first big AI company, so we should just let them to their thing, go slowly, get everything right, and avoid hype. Then Elon Musk founded OpenAI in 2015, murdered that plan, mutilated the corpse, and danced on its grave. Even after Musk left, the remaining team did everything to challenge everyone else to a race short of shooting a gun and waving a checkered flag.

OpenAI still hasn’t given a good explanation of why they did this. Absent anything else, I’m forced to wonder if it’s just “they’re just the kind of people who would do that sort of thing” - in which case basically any level of cynicism would be warranted.

I hate this conclusion. I’m trying to resist it. I want to think the best of everyone. Individual people at OpenAI have been very nice to me. I like them. They've done many good things for the world.

But the rationalists and effective altruists are still reeling from the FTX collapse. Nobody knew FTX was committing fraud, but everyone knew they were a crypto company with a reputation for sketchy cutthroat behavior. But SBF released many well-written statements about how he would do good things and not bad things. Many FTX people were likable and personally very nice to me. I think many of them genuinely believed everything they did was for the greater good.

And looking back, I wish I’d had a heuristic something like:

Scott, suppose a guy named Sam, who you’re predisposed to like because he’s said nice things about your blog, founds a multibillion dollar company. It claims to be saving the world, and everyone in the company is personally very nice and says exactly the right stuff. On the other hand it’s aggressive, seems to cut some ethical corners, and some of your better-emotionally-attuned friends get bad vibes from it. Consider the possibility that either they’re lying and not as nice as they sound, or at the very least that they’re not as smart as they think they are and their master plan will spiral out of control before they’re able to get to the part where they do the good things.

As the saying goes, “if I had a nickel every time I found myself in this situation, I would have two nickels, but it’s still weird that it happened twice.”

What We’re Going To Do Now

Realistically we’re going to thank them profusely for their extremely good statement, then cross our fingers really hard that they’re telling the truth.

OpenAI has unilaterally offered to destroy the world a bit less than they were doing before. They’ve voluntarily added things that look like commitments - some enforceable in the court of public opinion, others potentially in courts of law. Realistically we’ll say “thank you for doing that”, offer to help them turn those commitments into reality, and do our best to hold them to it. It doesn’t mean we have to like them period, or stop preparing for them to betray us. But on this particular sub-sub-topic we should take the W.

For example, they write:

We have attempted to set up our structure in a way that aligns our incentives with a good outcome. We have a clause in our Charter about assisting other organizations to advance safety instead of racing with them in late-stage AGI development.

The linked charter clause says:

We are concerned about late-stage AGI development becoming a competitive race without time for adequate safety precautions. Therefore, if a value-aligned, safety-conscious project comes close to building AGI before we do, we commit to stop competing with and start assisting this project. We will work out specifics in case-by-case agreements, but a typical triggering condition might be “a better-than-even chance of success in the next two years.”

This is a great start. It raises questions like: Who decides whether someone has a better-than-even chance? Who decides what AGI means here? Who decides which other projects are value-aligned and safety-conscious? A good followup would be to release firmer trigger-action plans on what would activate their commitments and what form their response would take, to prevent goalpost-moving later. They could come up with these themselves, or in consultation with outside experts and policy researchers.

This would be the equivalent of ExxonMobil making a legally-binding promise to switch to environmentalist mode at the exact moment that warming passes 1.5 degrees C - maybe still a little strange, but starting to sound more-than-zero meaningful.

(!create #reminders "check if this ever went anywhere" date 2024/03/01)

Their statement continues:

We think it’s important that efforts like ours submit to independent audits before releasing new systems; we will talk about this in more detail later this year. At some point, it may be important to get independent review before starting to train future systems, and for the most advanced efforts to agree to limit the rate of growth of compute used for creating new models. We think public standards about when an AGI effort should stop a training run, decide a model is safe to release, or pull a model from production use are important.

Reading between the lines, this sounds like it could be a reference to the new ARC Evals Project, where some leading alignment researchers and strategists have gotten together to work on ways to test safety.

Reading even further between the lines - at this point it’s total guesswork - OpenAI’s corporate partner Microsoft asked them for a cool AI. OpenAI assumed Microsoft was competent - they make Windows and stuff! - and gave them a rough draft of GPT-4. Microsoft was not competent, skipped fine-tuning and many other important steps which OpenAI would not have skipped, and released it as the Bing chatbot. Bing got in trouble for threatening users, which gave OpenAI a PR headache around safety. Some savvy alignment people chose this moment to approach them with their latest ideas (is it a coincidence that Holden Karnofsky published What AI Companies Can Do Today earlier that same week?), and OpenAI decided (for a mix of selfish and altruistic reasons) to get on board - hence this document.

If that’s even slightly true, it’s a really encouraging sign. Where OpenAI goes, other labs might follow. The past eight years of OpenAI policy have been far from ideal. But this document represents a commitment to move from safety laggard to safety model, and I look forward to seeing how it works out.