Misophonia: Beyond Sensory Sensitivity

...

Jake Eaton has a great article on misophonia in Asterisk.

Misophonia is a condition in which people can’t tolerate certain noises (classically chewing). Nobody loves chewing noises, but misophoniacs go above and beyond, sometimes ending relationships, shutting themselves indoors, or even deliberately trying to deafen themselves in an attempt to escape.

So it’s a sensory hypersensitivity, right? Maybe not. There’s increasing evidence - which I learned about from Jake, but which didn’t make it into the article - that misophonia is less about sound than it seems.

Misophoniacs who go deaf report that it doesn’t go away. Now they get triggered if they see someone chewing. It’s the same with other noises. Someone who gets triggered by the sound of forks scraping against a table will eventually get triggered by the sight of the scraping fork. Someone triggered by music will eventually get triggered by someone playing a music video on mute.

Maybe this isn’t surprising? Maybe it’s straight out of Pavlov - pair a neutral stimulus (like a flashing light) together with a negative stimulus (like an electric shock) often enough, and rats will learn to hate the flashing light. But usually Pavlov doesn’t work quite this well. People who hate school will happily walk past the schoolhouse; people who burn themselves on hot stoves will happily touch a cold stove; people who hate Donald Trump will laugh along with a lookalike Trump impersonator. In Pavlov’s experiments, the conditioned response fades to extinction after the conditioned stimulus stops correlating with the unconditioned stimulus. But deaf misophoniacs will still hate the sight of chewing the millionth time they see it.

The research gets weirder. If you trick misophoniacs into thinking their trigger sounds are something else, they won’t get triggered. In this study, scientists played people who hated chewing sounds a video (with audio) of someone chewing; unsurprisingly, they hated it. Then they played them a video of someone walking on squelching snow, but the audio track was secretly actually the same chewing sounds. It looked like the snow was making the noise - now the misophoniacs didn’t hate it!

Again, there are reasonable explanations. This is a variant of the McGurk effect:

The man is saying the same syllable each time, but depending on which picture of his mouth moving you look at, you hear it differently. Your vision is context-modulating your hearing, but it just sounds like hearing something.

But some misophoniacs say that they’re only triggered by specific people - usually those close to them. If some rando chews loudly, they’ll be mildly annoyed; if their brother does, they’ll flip out. Probably there’s a reasonable explanation here too, but at this point maybe we should also be considering a larger-scale update.

So is misophonia sort of fake?

I have a mild version, and it sure doesn’t feel fake. From the outside, you probably have all these great ideas for how you would overcome it - try gradual desensitization! Try flooding! Fake it ‘til you make it! Just concentrate really hard and think ‘Sound can’t hurt me’! I’ve tried all of these and they don’t work, sorry, sound is still enraging. It’s not chewing for me; thankfully, I missed out on that one. My trigger is certain kinds of background conversation and music - less about the auditory details than about a certain part of my sensory periphery where I’m trying not to concentrate on it but failing. It hasn’t quite ruined my life, but was a big financial drain when I was younger - across three or four different cities, I drove away all my roommates by yelling at them for making noise, and ended up living on my own at much higher cost. There have been times when I wore giant construction earphones whenever I went outside, although things aren’t quite that bad now.

But even as misophonia makes me miserable - even as I absolutely fail to overcome it - I can’t help feeling like it’s sort of fake. I’d already noticed something like the thing about people close to me. The way I thought of it was something about righteous anger. The sound of the wind in the trees barely bothered me at all, because there was no one to get angry at. Sounds that were natural parts of the social order were nearly as benign - I didn’t like hearing the bus driver announce the next stop, but it was an inevitable part of the bus-riding experience and I was resigned to it. But if a group of gangbangers scared the kids out of the nearby park and put on loud music while smoking drugs, I would go through the roof. Some utilitarian philosopher once said that while there are practical considerations for punishment nobody really deserves to suffer and in some cosmic sense even Hitler doesn’t truly deserve so much as a stubbed toe. I’m pretty sympathetic to that perspective when we’re just talking about genocidal dictators. But people who play loud music in the park - no, they need to suffer.

Even worse, I found myself seeking out the anger. I would turn on my big box fan, turn on my white noise machine, put in my earplugs, put my giant construction earphones on over them, and that would pretty much work. But I’d find myself straining to see if I could still catch a couple of beats of music through it all. If there was any chance that one single sound wave of the white-noise-fan-amalgam I was hearing actually came from the music, then I would have to get mad all over again. I realize this is stupid - if I can’t even tell if the music is still on, then what’s the problem? But there I was, straining to detect stray notes at the edge of my capability, in order to assess how angry I should be.

How did I get this way? Self-report is unreliable, but I remember when I was seven years old I would make noise and bother my parents. In the process of telling me not to do this, my dad complained to me that when he was in the process of falling asleep, there was about a fifteen minute window of half-asleepness where any interruption would jolt him awake so thoroughly that he wouldn’t be able to try falling asleep again for hours. Something about that resonated with me, and since then I’ve been the same way. Was I always like that, and his comment just called my attention to it? That’s not how I remember things, but who knows?

Then when I was twenty-five or so, this trouble with falling asleep was a big enough deal that I would always be telling my roommate to keep it down. One night my roommate complained that I seemed to have some weird pathological problem with noise way outside the normal distribution. I’d never thought about it before, but again, something resonated, that became “part of my identity” against my will, and from then on I was intolerable about any noise-related issue. Again, the simple explanation is that I was already like that - hence my roommate telling me I was like that. Again, that’s not how I remember things.

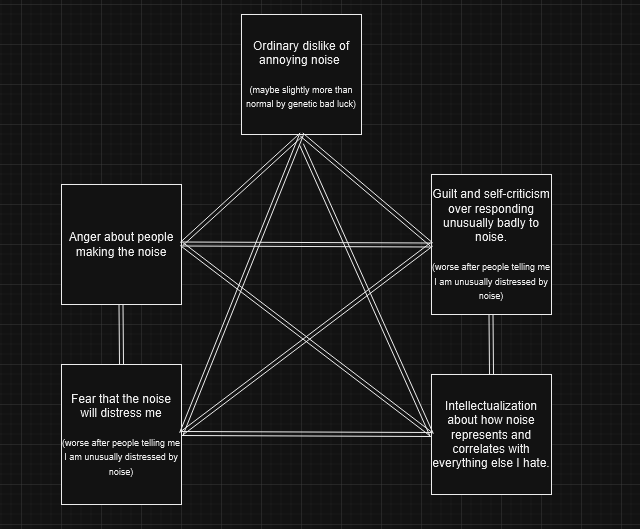

Is this the dreaded “social contagion” of mental illness? I’m not sure. But I imagine all of these things interacting in some kind of malicious network. Nobody likes loud noises when they’re trying to concentrate on something else. But somehow it spreads out from a natural ordinary distaste for the noise, to anger about the people making the noise, to fear and guilt that I might be some kind of special set-apart person who is especially bad at tolerating noise, to weird intellectualized thought-loops about how the noise symbolizes the decay of society, and back again - such that even if the noise would normally bother me for a minute and then fade into the background, the overall network never stopped looping and pinging my anger and distress buttons.

This is all just introspection. But it would explain some of research - why the phenomenon can persist even without the noise (eg in deaf people), why context matters so much, why it’s worse with close friends and family (you’ve already told them you have misophonia, so insofar as their continued noise indicates they don’t care about you enough to stop, it’s easier to be sad and angry about them).

I suggested Jake think of this in the context of my old trapped priors post. Suppose that in reality, noise is annoying but nothing more. For whatever reason, someone gets stuck thinking noise is the worst thing in the world. In a normal situation, they should gradually unlearn this association - each time noise happens, they’ll update a little bit of the way back to “annoying and nothing more” until they’re all the way there. For this updating process to fail, the noise must genuinely provoke misery each time. My claim is that this whole learned network of negative things and noise ensures that each instance of noise will provoke enough negative associations to sustain the misophonia and the network of context clues that makes the misophonia work. The knot has so many dependencies that the brain’s natural updating process can’t untangle it in the amount of time it takes to form an emotion, so the update fails, or goes the wrong direction.

Cognitive behavioral therapists love this kind of thing - it’s a lot like what they call belief networks or core beliefs - but misophonia has so far resisted CBT. Eaton says the only thing that really helped him was a weeklong silent meditation retreat. This started out badly - he was in a room full of people being very quiet, and “every time the person next to me swallowed, I felt first a brief ripple of anger at the sound itself, followed by a larger wave of frustration at my reaction to it”. But as he got deeper into meditation, he was able to “notice the space between sensation and reaction . . . for the first time, I could choose to ignore the signal”. He doesn’t say whether it helped long-term, but it wouldn’t surprise me if it did. Meditation is about focusing hard enough on mental processes that you see them for what they really are (in the sense that noise “really is” annoying-and-nothing-more), then observing your reaction as a separate event. Do this well enough, and it potentially allows updating on the true value.

I talk a big talk, but so far knowing all of this hasn’t helped me tolerate noise more, not even a little bit.