Mantic Monday: The Monkey's Paw Curls

...

The Monkey’s Paw Curls

Isn’t “may you get exactly what you asked for” one of those ancient Chinese curses?

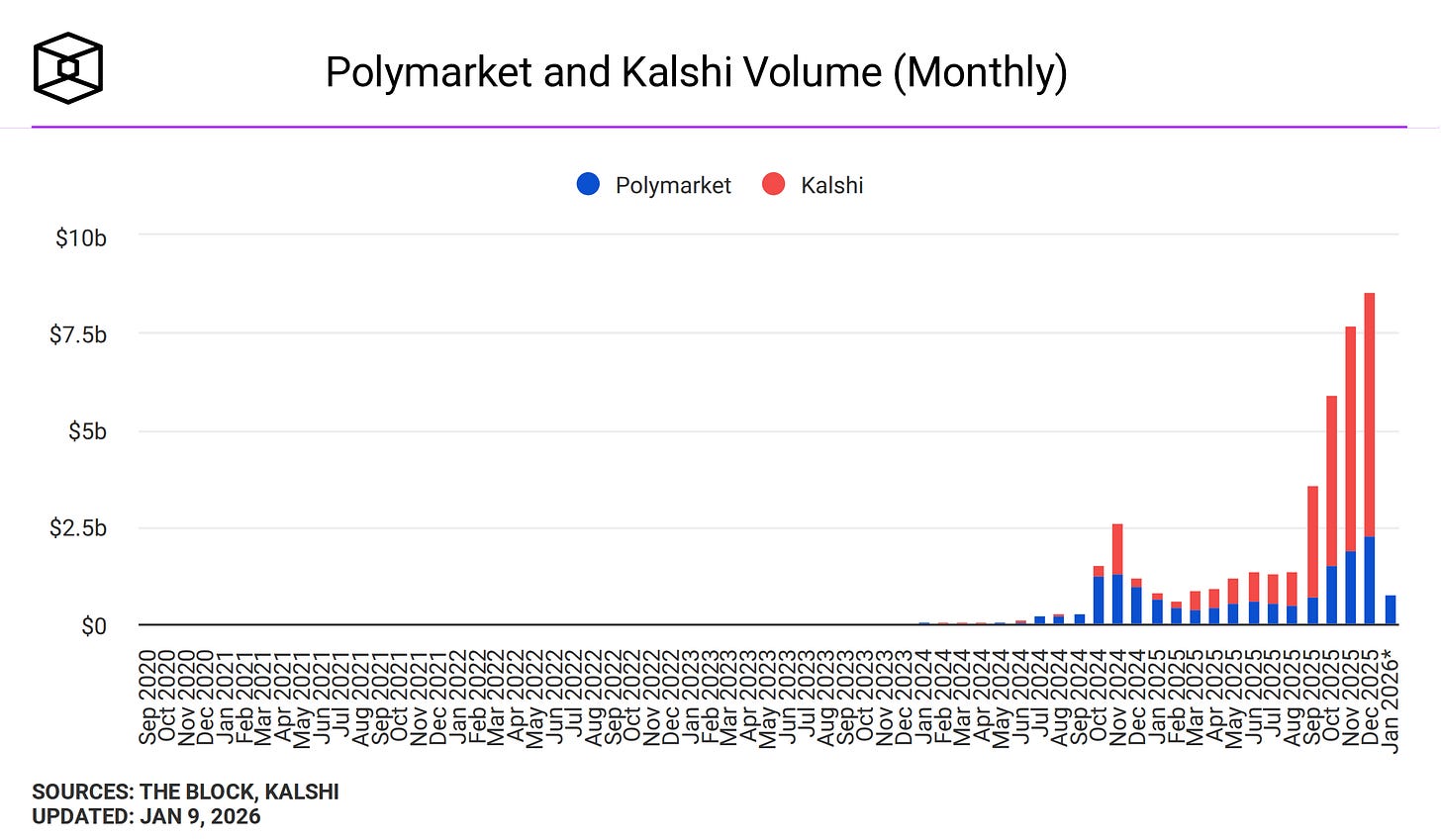

Since we last spoke, prediction markets have gone to the moon, rising from millions to billions in monthly volume.

For a few weeks in October, Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan was the world’s youngest self-made billionaire (now it’s some AI people). Kalshi is so accurate that it’s getting called a national security threat.

The catch is, of course, that it’s mostly degenerate gambling, especially sports betting. Kalshi is 81% sports by monthly volume. Polymarket does better - only 37% - but some of the remainder is things like this $686,000 market on how often Elon Musk will tweet this week - currently dominated by the “140 - 164 times” category.

(ironically, this seems to be a regulatory difference - US regulators don’t mind sports betting, but look unfavorably on potentially “insensitive” markets like bets about wars. Polymarket has historically been offshore, and so able to concentrate on geopolitics; Kalshi has been in the US, and so stuck mostly to sports. But Polymarket is in the process of moving onshore; I don’t know if this will affect their ability to offer geopolitical markets)

Degenerate gambling is bad. Insofar as prediction markets have acted as a Trojan Horse to enable it, this is bad. Insofar as my advocacy helped make this possible, I am bad. I can only plead that it didn’t really seem plausible, back in 2021, that a presidential administration would keep all normal restrictions on sports gambling but also let prediction markets do it as much as they wanted. If only there had been some kind of decentralized forecasting tool that could have given me a canonical probability on this outcome!

Still, it might seem that, whatever the degenerate gamblers are doing, we at least have some interesting data. There are now strong, minimally-regulated, high-volume prediction markets on important global events. In this column, I previously claimed this would revolutionize society. Has it?

I don’t feel revolutionized. Why not?

The problem isn’t that the prediction markets are bad. There’s been a lot of noise about insider trading and disputed resolutions. But insider trading should only increase accuracy - it’s bad for traders, but good for information-seekers - and my impression is that the disputed resolutions were handled as well as possible. When I say I don’t feel revolutionized, it’s not because I don’t believe it when it says there’s a 20% chance Khameini will be out before the end of the month. The several thousand people who have invested $6 million in that question have probably converged upon the most accurate probability possible with existing knowledge, just the way prediction markets should.

I actually like this. Everyone is talking about the protests in Iran, and it’s hard to gauge their importance, and knowing that there’s a 20% chance Khameini is removed by February really does help to place them in context. The missing link seems to be between “it’s now possible to place global events in probabilistic context → society revolutionized”.

Here are some possibilities:

Maybe people just haven’t caught on yet? Most news sources still don’t cite prediction markets, even when many people would care about their outcome. For example, the Khameini market hasn’t gotten mentioned in articles about the Iran protests, even though “will these protests succeed in toppling the regime?” is the obvious first question any reader would ask.

Maybe the problem is that probabilities don’t matter? Maybe there’s some State Department official who would change plans slightly over a 20% vs. 40% chance of Khameini departure, or an Iranian official for whom that would mean the difference between loyalty and defection, and these people are benefiting slightly, but not enough that society feels revolutionized.

Maybe society has been low-key revolutionized and we haven’t noticed? Very optimistically, maybe there aren’t as many “obviously the protests will work, only a defeatist doomer traitor would say they have any chance of failing!” “no, obviously the protests will fail, you’re a neoliberal shill if you think they could work” takes as there used to be. Maybe everyone has converged to a unified assessment of probabilistic knowledge, and we’re all better off as a result.

Maybe Polymarket and Kalshi don’t have the right questions. Ask yourself: what are the big future-prediction questions that important disagreements pivot around? When I try this exercise, I get things like:

Will the AI bubble pop? Will scaling get us all the way to AGI? Will AI be misaligned?

Will Trump turn America into a dictatorship? Make it great again? Somewhere in between?

Will YIMBY policies lower rents? How much?

Will selling US chips to China help them win the AI race?

Will kidnapping Venezuela’s president weaken international law in some meaningful way that will cause trouble in the future?

If America nation-builds Venezuela, for whatever definition of nation-build, will that work well, or backfire?

Some of these are long-horizon, some are conditional, and some are hard to resolve. There are potential solutions to all these problems. But why worry about them when you can go to the moon on sports bets?

Annals of The Rulescucks

The new era of prediction markets has provided charming additions to the language, including “rulescuck” - someone who loses an otherwise-prescient bet based on technicalities of the resolution criteria.

Resolution criteria are the small print explaining what counts as the prediction market topic “happening'“. For example, in the Khameini example above, Khameini qualifies as being “out of power” if:

…he resigns, is detained, or otherwise loses his position or is prevented from fulfilling his duties as Supreme Leader of Iran within this market's timeframe. The primary resolution source for this market will be a consensus of credible reporting.

You can imagine ways this definition departs from an exact common-sensical concept of “out of power” - for example, if Khameini gets stuck in an elevator for half an hour and misses a key meeting, does this count as him being “prevented from fulfilling his duties”? With thousands of markets getting resolved per month, chances are high that at least one will hinge upon one of these edge cases.

Kalshi resolves markets by having a staff member with good judgment decide whether or not the situation satisfies the resolution criteria.

Polymarket resolves markets by . . . oh man, how long do you have? There’s a cryptocurrency called UMA. UMA owners can stake it to vote on Polymarket resolutions in an associated contract called the UMA Oracle. Voters on the losing side get their cryptocurrency confiscated and given to the winners. This creates a Keynesian beauty contest, ie a situation where everyone tries to vote for the winning side. The most natural Schelling point is the side which is actually correct. If someone tries to attack the oracle by buying lots of UMA and voting for the wrong side, this incentivizes bystanders to come in and defend the oracle by voting for the right side, since (conditional on there being common knowledge that everyone will do this) that means they get free money at the attackers’ expense. But also, the UMA currency goes up in value if people trust the oracle and plan to use it more often, and it goes down if people think the oracle is useless and may soon get replaced by other systems. So regardless of their other incentives, everyone who owns the currency has an incentive to vote for the true answer so that people keep trusting the oracle. This system works most of the time, but tends towards so-called “oracle drama” where seemingly prosaic resolutions might lie at the end of a thrilling story of attacks, counterattacks, and escalations.

Here are some of the most interesting alleged rulescuckings of 2026:

Mr Ozi: Will Zelensky wear a suit? Ivan Cryptoslav calls this “the most infamous example in Polymarket history”. Ukraine’s president dresses mostly in military fatigues, vowing never to wear a suit until the war is over. As his sartorial notoriety spread, Polymarket traders bet over $100 million on the question of whether he would crack in any given month. At the Pope’s funeral, Zelensky showed up in a respectful-looking jacket which might or might not count. Most media organizations refused to describe it as a “suit”, so the decentralized oracle ruled against. But over the next few months, Zelensky continued to straddle the border of suithood, and the media eventually started using the word “suit” in their articles. This presented a quandary for the oracle, which was supposed to respect both the precedent of its past rulings, and the consensus of media organizations. Voters switched sides several times until finally settling on NO; true suit believers were unsatisfied with this decision. For what it’s worth, the Twitter menswear guy told Wired that “It meets the technical definition, [but] I would also recognize that most people would not think of that as a suit.”

Domer: Will Ukraine agree to the US mineral deal? AFAICT, this is the only case where the oracle genuinely broke down (as opposed to a legitimate disagreement). In February, it looked like both America and Ukraine had agreed to a mineral deal, but the oracle considered the question and decided this didn’t count as a full agreement (and indeed, the apparent agreement then fell apart). In March, a cabal of YES holders tried again. They waited for a time when all Polymarket employees would be out of the office, and when not too many people would be voting on the decentralized resolution oracle, then spammed it with calls to resolve to YES based on an argument that the February agreement had qualified after all. The YES holders and not-particularly-plugged-in oracle voters pushed the vote towards YES. Then, with two minutes to spare, a Polymarket employee showed up and said that Polymarket’s opinion was that it should be NO. This was technically framed as a recommendation to oracle voters, but it is so effective in establishing the Schelling point that it’s practically always followed. However, in this case, there were only two minutes left, which wasn’t enough time for the voters to change their mind. Seeing that the resolution was trending towards yes, the Polymarket representatives, not wanting to break their streak of always establishing the Schelling point, changed their own opinion to YES, and the final vote was YES 99%.

Domer: How many people watched the Oscars on 3/5/25?: Kalshi’s resolution criteria for this market said they would resolve it when a major news source published Oscar viewership numbers. A few minutes after the Oscars, NYT published preliminary viewership numbers, without any caveats saying they were preliminary. The next day, they published another article saying that actually, the real viewership numbers were higher. Kalshi decided that the letter of the resolution criteria was met when NYT published its first article, and that NYT changing its opinion didn’t imply that Kalshi should change the resolution. Traders who bet on the later (ie correct) numbers were unsatisfied with this decision.

NYPost: Will America invade Venezuela? On January 3, the US bombed Venezuela, sent in a Special Forces team that successfully captured President Maduro, and announced that they would thenceforward “run the country” (a claim they later walked back). Does this qualify as an “invasion”? Polymarket’s resolution criteria defined “invasion” as “a military offensive intended to establish control over any portion of Venezuela”. It didn’t seem like the US was trying to establish control over Venezuelan territory, exactly, so they resolved NO. Traders who bet on YES were unsatisfied with this decision.

With one exception, these aren’t outright oracle failures. They’re honest cases of ambiguous rules.

Most of the links end with pleas for Polymarket to get better at clarifying rules. My perspective is that the few times I’ve talked to Polymarket people, I’ve begged them to implement various cool features, and they’ve always said “Nope, sorry, too busy figuring out ways to make rules clearer”. Prediction market people obsess over maximally finicky resolution criteria, but somehow it’s never enough - you just can’t specify every possible state of the world beforehand.

The most interesting proposal I’ve seen in this space is to make LLMs do it; you can train them on good rulesets, and they’re tolerant enough of tedium to print out pages and pages of every possible edge case without going crazy. It’ll be fun the first time one of them hallucinates, though.

…And Miscellaneous N’er-Do-Wells

I include this section under protest.

The media likes engaging with prediction markets through dramatic stories about insider trading and market manipulation. This is as useful as engaging with Waymo through stories about cats being run over. It doesn’t matter whether you can find one lurid example of something going wrong. What matters is the base rates, the consequences, and the alternatives. Polymarket resolves about a thousand markets a month, and Kalshi closer to five thousand. It’s no surprise that a few go wrong; it’s even less surprise that there are false accusations of a few going wrong.

Still, I would be remiss to not mention this at all, so here are some of the more interesting stories:

Fhantombets: Who will win the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize? Twelve hours before the announcement, someone placed a large Polymarket bet on Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, bringing her probability from 4% to 73%. When Machado later won, observers suspected insider trading. But an account named fhantombets claims to have interviewed the winning trader; although he did not reveal his exact strategy, the interview better matches a story where he was good at navigating WordPress directories, and found that the Nobel team put a draft of the announcement up early in a nonpublic part of their WordPress site. He won about $70,000.

LuishXYZ: Will the Russians capture Myrnohrad? This is a small town in Ukraine that the Russians obviously were not going to capture; the Polymarket price trended toward zero. The resolution criteria named maps by the well-regarded Institute For The Study of War as canon. A few hours before resolution, ISW updated their maps to show the the town captured by Russia, which was definitely false. Polymarket resolved to YES, and the fictional Russian advance disappeared. The Institute then issued a statement saying the map update was “unapproved”, and fired one of its staffers who had presumably been involved. The cheater’s exact winnings are unknown, but based on the size of the market are probably mid-6-digits.

TechCrunch: What words will be used in Coinbase’s earnings call? Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong delivered the company’s “earnings call”, ie a speech to investors about its recent progress. At the end, he said “I've been tracking the prediction market about what Coinbase will say on their next earnings call, and I just want to add here the words Bitcoin, Ethereum, Blockchain, Staking, and Web3 to make sure we get those in before the end of the call”. Armstrong is worth $10 billion and doesn’t need to manipulate a $50,000 market for the money - he later described his comments as “trolling”. Other crypto executives condemned the move, with one saying that “you need your head examined if you think it’s cute or clever or savvy that the CEO of the biggest company in this industry openly manipulated a market.” I might need my head examined, because I think it’s at least kind of funny.

Forbes: Who will rank highest on Google Search volume this year? A trader called AlphaRaccoon got 22/23 of these Polymarket questions right, and has a history of implausibly good performance on Google-related questions. They basically have to be a Google insider, but (since all of this is done through crypto) nobody has a good way to figure out who. They made $1 million.

NPR: Will Maduro be captured? Just before the secret operation that captured Maduro, someone placed a mysterious $32,000 wager on YES. Was this insider trading by someone in the administration or military? Nobody knows, since the profits go to an anonymous crypto wallet. But the article mentions that the crypto wallet appears to be cashing out through regulated KYC-compliant US exchanges, which suggests they’re not very worried about their identity getting discovered. Maybe they just got lucky after all.

AlanMCole: How long will Karoline Leavitt speak at the White House briefing? Karoline Leavitt is Trump’s press secretary. On January 7, she held an ordinary press briefing. Kalshi had its usual market about how long the briefing would last, divided into bins of greater than vs. less than 65 minutes. At the 64:24 mark, Leavitt ended the conference in what appeared to be a sudden manner, and the “less than 65 minutes” bin shot from 2% to 100%. A viral tweet convinced many people that Leavitt must have been insider trading, but Cole counterargued that Leavitt could only have won about $4,000 from the market, which probably isn’t enough to risk one’s job as White House Press Secretary. Sometimes people just end press conferences at weird times.

Cole concluded:

Now, some opinions and generalizations, as someone who looks at prediction markets plenty (I’ll probably write something about my own experience with them at some point.)

1. This market, like many of them, is pretty stupid. I like substantive markets; this isn’t substantive.

2. The major prediction markets have a wildly undisciplined comms strategy where any attention is good attention, and they love implying all sorts of crazy wild west stuff is going on to get attention.

3. People do bet on things potentially subject to manipulation or insider trading. But usually the markets like that (such as duration of press conference, or stupid “what will be mentioned” markets) are small, especially relative to the wealth of key decisionmakers.

4. Losers in markets are huge whiners, and the more frivolous and tiny their bets, the more likely they are to whine.

Sometimes in sports it’s pretty egregious. They’ll get mad at a team for running out the clock when ahead but under some spread they bet on.

5. Lower-quality financial news often doesn’t pay much attention to quantity. (For example, dumb stories about how a decisionmaker has a conflict of interest because they’re invested in an index fund which is 3 percent comprised of some company.)

6. Given the platforms’ undisciplined social media strategy of “promote prediction market chatter no matter what kind of chatter it is,” I don’t think this tweet rises even to the status of “lower-quality financial news.”

Kalshi’s team, whatever their faults, are extraordinarily efficient at getting batched approvals of many near-identical markets with slight parameter variation; I’ve seen Tarek speak about this on Odd Lots. The result is they’ve got TONS of them, for better or worse.

You’re gonna see 1-in-100 upsets on tiny Kalshi markets for as long as this regulatory equilibrium holds, even if nothing unusual is going on, simply because they’re publishing hundreds (thousands?) of markets per day.

There’s a saying that you can’t con an honest man. This isn’t exactly true. But it’s easier to con people who are playing in a “what words will Brian Armstrong say today” market than people who are trying to do something useful, and I have trouble feeling sorry for these people when Brian Armstrong says silly words.

Conditional Markets: A Modest Proposal

Conditional markets (“decision markets”) are the strongest case for prediction markets potentially being revolutionary.

The idea is - you may want to base a decision (like which candidate to elect) on an outcome (like how they’ll affect the economy). So you make two markets:

If the Democrat gets elected, will the economy be good four years later?

If the Republican gets elected, will the economy be good four years later?

…and if one market is higher than the other, then you’ve successfully forced everyone to settle on a canonical probability of which candidate will be better for the economy.

The fatal flaw is confounding by noncausal pathways. For example, bettors might reason: suppose for some extrinsic reason (let’s say someone struck oil) the economy is very good from 2026 - 2028. Then in 2028, people will feel better about Trump, and are more likely to elect Vance. And if the economy is very good from 2026 - 2028, then it’s more likely to be very good from 2028 - 2032 (the oil is still there). Therefore, we should bet up the Republicans → good market, and bet down the Democrats → good market, before we even think about whether Republicans or Democrats will do a better job with the economy. Therefore, this can’t be a good way to determine whether Republicans or Democrats will do a better job with the economy.

Here’s a potential workaround I’ve never seen before: suppose you create a set of conditional prediction markets as above. Then you create a set of secondary markets, asking bettors to predict the price of the first set of markets on the day before Election Day.

On the day before Election Day, either they’ll have struck oil, or they won’t have. So regardless of the oil situation, people will be factoring in only the true effect of the parties’ policies. If you ask people today to predict those markets, they’ll be predicting the true effect of the policies. Giving an example with numbers on everything (thanks to AI for gaming this out with me):

- 25% chance of striking oil

- NO OIL WORLD (75% chance):

------ D increases GDP 5%, R increases GDP 2%

------ D wins 50%, R wins 50%

- YES OIL WORLD (25% chance):

------ D increases GDP 10%, R increases GDP 7%

------ D wins 10%, R wins 90%

Total P(R wins) = 0.75×0.5 + 0.25×0.9 = 0.375 + 0.225 = 0.6

Total P(D wins) = 0.75×0.5 + 0.25×0.1 = 0.375 + 0.025 = 0.4

Naive conditional market calculation

E[GDP | R wins] = (0.225×7% + 0.375×2%) / 0.6 = (1.575% + 0.75%) / 0.6 = 3.875%

E[GDP | D wins] = (0.025×10% + 0.375×5%) / 0.4 = (0.25% + 1.875%) / 0.4 = 5.3125%

Naive difference: 5.3125% - 3.875% = 1.4375% (understates the true 3% causal effect of D policies)

Secondary market calculation

On Election Eve, conditional on oil found: R market = 7%, D market = 10%

On Election Eve, conditional on no oil: R market = 2%, D market = 5%

E[Today's market on the Election Eve R market price] = 0.25×7% + 0.75×2% = 1.75% + 1.5% = 3.25%

E[Today's market on the Election Eve D market price] = 0.25×10% + 0.75×5% = 2.5% + 3.75% = 6.25%

Secondary market difference: 6.25% - 3.25% = 3% (exactly the true causal effect)This doesn’t completely solve the conditional problem. There could be residual correlations based on hidden variables that affect the outcome of interest (in this case the election) without being known to bettors even on Election Day Eve. A trivial example is some extraordinary event which happens at 12:01 AM on Election Day. A more subtle example goes something like: suppose the economy is subtly good, nobody has managed to aggregate the statistics and figure this out in a legible way yet, and each individual person still only has private knowledge that the economy is good for him- or her-self. They might still be more likely to vote Republican based on their own private economic optimism, and then the hidden goodness of the economy might become manifest and improve GDP during the next term. Yes, this example is a stretch; maybe I’m missing better ones, or maybe this is a silly edge case failure mode that shouldn’t bother us in real life.

What about interaction effects - for example, if Democrats were better at milking a good economy and making it even better, but Republicans were better at correcting a distressed economy and bringing it back to average, would that break the link between the primary and secondary markets? This is beyond my poor mathematical ability, but the AIs claim it’s not a problem - the secondary market workaround still ensures the correct difference.

Bonus question: Is there a way to simplify this so that we don’t have to run all four markets?

The End Of The Beginning

When I started this column in 2021, I dreamed of a time when there would be big legal prediction markets on important topics. That’s come true. There have been some small benefits, but not the epistemic wonderland I hoped for. So what now? Do we pat Shayne Coplan and Tarek Mansour on the back, let them enjoy their superyachts, and otherwise forget about this space?

I see two ways forward.

The first is to continue praying for the original Manifold vision - a prediction market site which offers:

Real money markets

…that are user-created, user-resolved, and potentially subjective, giving the user a percent of the volume as a reward for writing/managing/promoting the question.

…and are otherwise easy to use (good interface, high volume, legal in the US)

I’ve been asking for this so long that Nuno Sempere dubbed it the Siskind Cube:

When I ask Manifold why they won’t add 1, they say that Polymarket and Kalshi already dominate the space, and they have other, more interesting plans (to be announced soon). When I ask Polymarket why they won’t do 2, the answer is a combination of regulatory issues, fear that people would write bad resolution criteria and it would reflect badly on them, and there always being something more important to do. I haven’t asked Kalshi, but their answer would definitely be regulatory.

I still think this is a billion dollar bill waiting to be picked up.

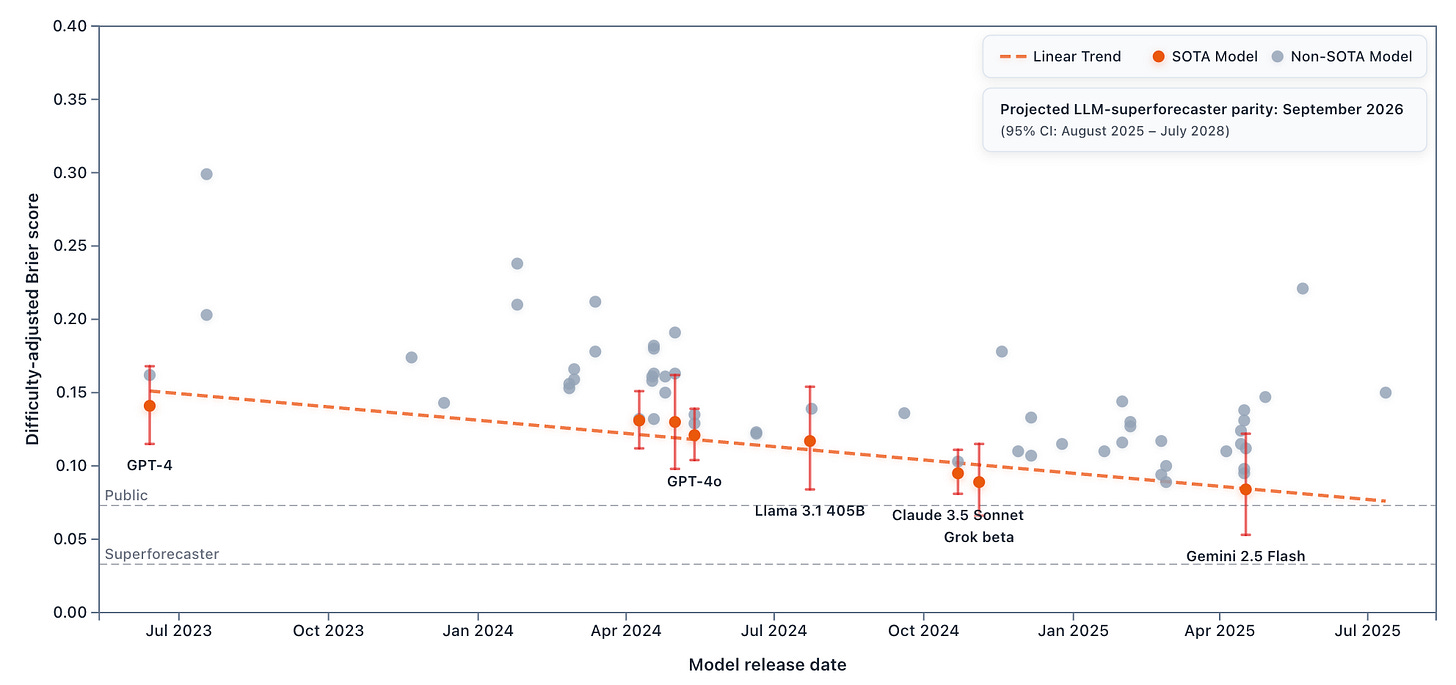

The second is to conclude that prediction markets’ role in God’s plan was only to provide the foundation for AI superforecasters - the training data, the benchmarking arena, and the pot of money that rewards innovation. Once AI superforecasters are developed, then (for all that the rest of us care), the markets themselves can wither away into the sports gambling casinos they so desperately want to become. The Forecasting Research Institute’s linear extrapolation shows AIs are on track to match top humans “by late 2026”

Once superforecaster bots can consider questions for pennies, we can create play-money prediction markets for them, and trust that the consensus answers will be as canonical as perfectly-designed real money prediction markets would be for humans.

Expecting this to happen in 2027, what will that look like, and who should we invest in? Maybe this benefits Manifold - all of a sudden, play-money markets become much more important, and quantity becomes more important at the expense of quality. But branding and perception are important, so the victory could also go to someone who designs around superforecasting bots from the ground up.

The Trump administration has signaled willingness to allow innovation in this space, so we have at least another three years of friendly regulators - three years when autoforecasters will be improving quickly and AI will be lowering the barrier to starting new businesses. A lot can happen during that time.

This Month In The Markets

I’ve previously written about Orban under the assumption that he’s a dictator-adjacent figure who’s hacked Hungary’s election system so that he can’t possibly lose. That perspective looked correct as recently as last year, but his chances have been swinging around recently, and are currently below 50-50. The election is April 12.

After Maduro’s capture, control has passed to his vice-president, with the US saying they’re mostly interested in extracting oil. The markets give her a 51% chance of staying on for the long haul. And here is a long list of all major Venezuela-related prediction markets, including how the country will be classified in the Economist’s 2027 Democracy Index (40% chance still an authoritarian regime), and a very subjective one about whether the author will feel that Venezuelans are “better off” at the end of the year (65% chance)

Strange things happening on the COVID lab leak market, which has declined to 27%. This peaked at about 85% in 2023, declined a bit around the Rootclaim debate and my article on it, then stayed around 50-50 for a year or so. But for the past eight months, it’s been gradually trending downward, with no end in sight. Some of the change probably involves the discovery of a natural bat coronavirus with a furin cleavage site last October, but I’m surprised by the extent of the decline.

This market is up ten points on news that GDP last quarter rose 4.3% with no increase in hours worked.

A California union has announced a campaign to force a 2026 ballot proposition that levies a “one time” wealth tax on billionaires; the mere threat of this tax has spooked several billionaires, including Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, into leaving the state (the initiative would apply to anyone residing in California as of 1/1/2026, so there’s incentive for them to leave proactively). The markets above are the first attempts I’ve seen to estimate the chance of it actually passing.

Trump Greenland market; went way up upon Maduro capture and subsequent reignition of the discussion. Lest you worry that this is only tracking the chance of getting a military base or some other small acquisition, the creator specified that:

…this market is about whether Greenland or a meaningful portion of it becomes part of America, not about minor acquisitions like a single building or small plot of land.

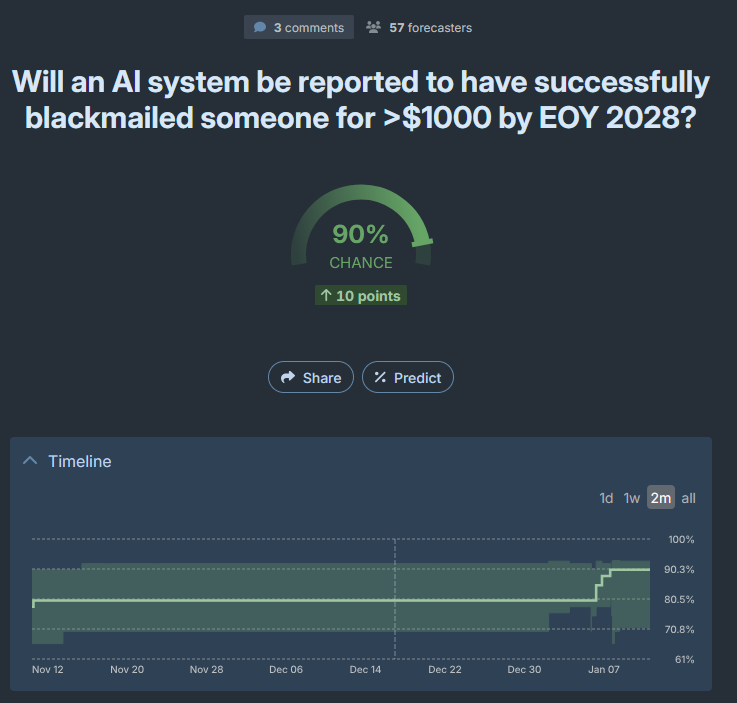

Here’s a pretty crazy Metaculus question - the resolution criteria specify it’s not about scammers using AIs to blackmail their victims, it’s about an AI independently developing and executing a blackmail plan without human prompting or support. Sometime like this has already happened in toy experiments conducted by safety teams when all the conditions were exactly right, but forecasters seem confident it will happen in real life sometime in the next three years. I don’t understand what’s going on here, and I’m going to recheck this question after signal-boosting it to see if it changes.

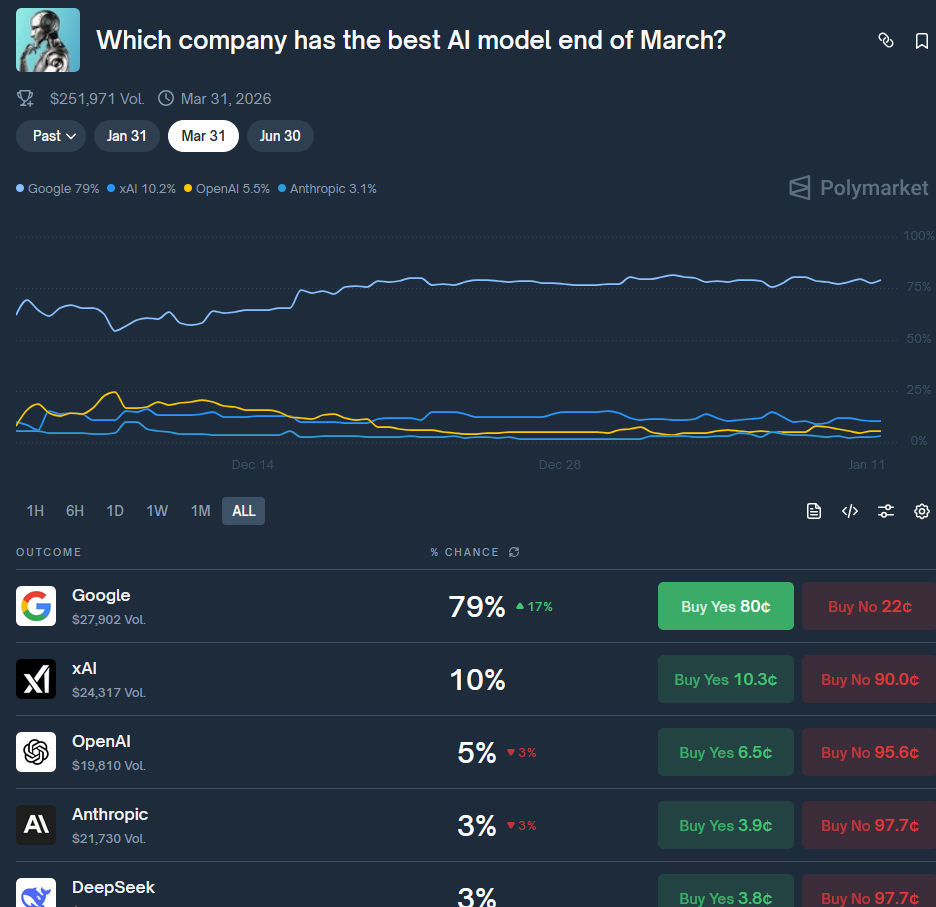

Polymarket has a few of these “who has the best AI when?” markets - resolution is usually position on the LMArena Leaderboard, which usually but not always mirrors common-sense consensus. I get more interested in these the further out they go, but the June version is bizarre (it doesn’t even list Google as an option), and there’s nothing past mid-year. Other implied claims from Polymarket’s tech section: only 44% chance Anthropic will still dominate coding by late March; Anthropic and (especially) OpenAI probably won’t IPO this year; xAI will call their next model Grok 4.20 (of course).

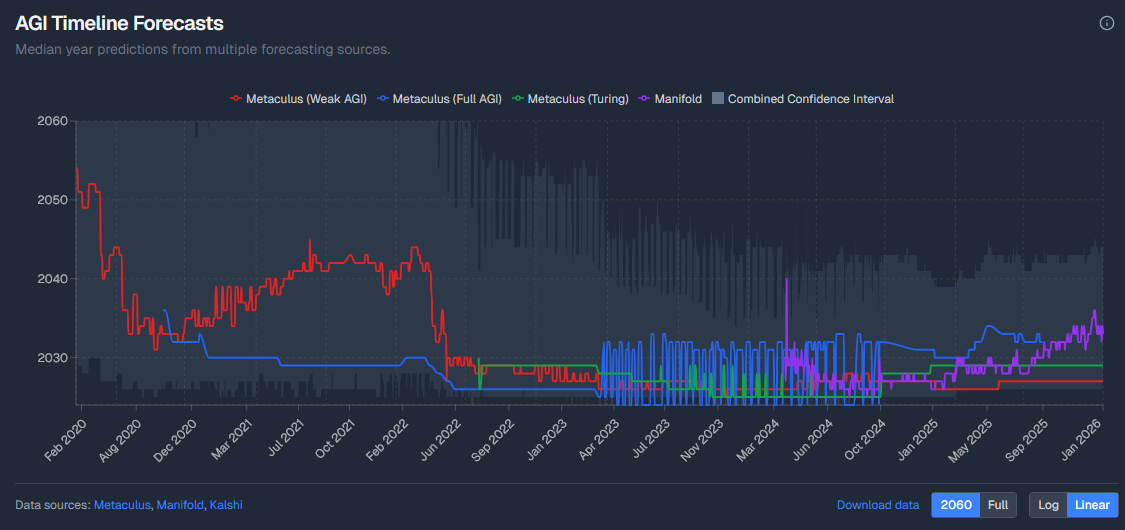

And Nathan Young has put together an AGI timelines forecasting dashboard:

Elsewhere In Prediction Markets

1: New York Magazine profiles Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan:

The only child of South African college professors, Coplan grew up living with just his mother. He describes his father as a “mad scientist” who has studied panic disorder and depression. His mom taught in the film departments at NYU and Columbia and cast young Shayne in her own work.

The obvious next question - is Coplan Sr’s work on panic disorder any good? Answer: yes! - he co-published with Donald Klein, whose ventilatory hypothesis of panic revolutionized my understanding of the condition. Great Families theory undefeated.

2: Donald Trump’s company Truth Social said in October that it’s becoming the world’s first social media platform offering prediction markets via a partnership with crypto.com. This isn’t quite what I want - I don’t think users can create their own prediction markets - but it’s a step forward. Also, think about how much money someone’s going to make by taking the pro-left-wing side of all those trades!

3: You have five days left to submit your predictions in the ACX/Metaculus 2026 Prediction Contest.

4: Forecasting Research Institute has established a Longitudinal Expert AI Panel of scientists and forecasters to map changing expert opinion on AI over time. Experts predict “significantly less AI progress than leaders of frontier AI companies” but “much faster AI progress than the general public.

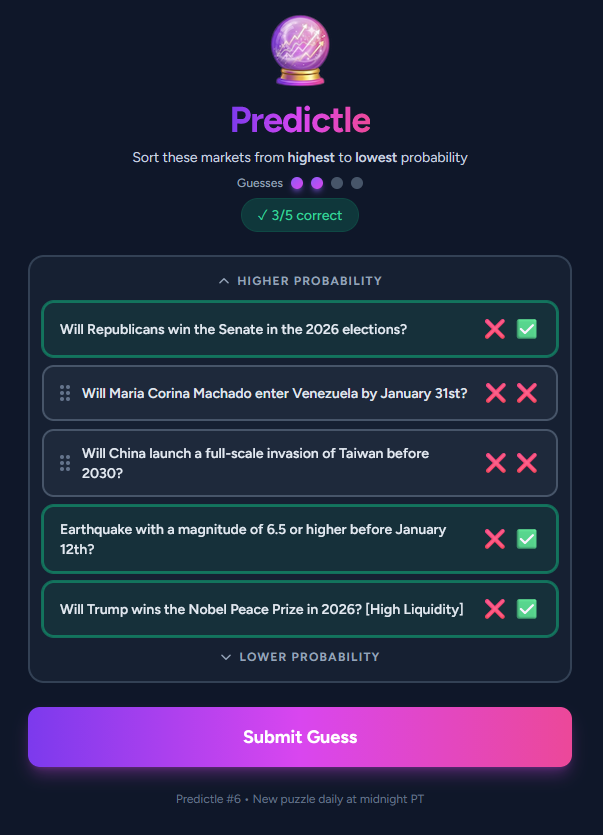

5: Manifold has launched Predictle, a Wordle-inspired game where you have to rank events by the (Manifold-endorsed) probability of them happening: