Link: Troof On Nootropics

...

Should have signal-boosted this earlier, forgot, sorry.

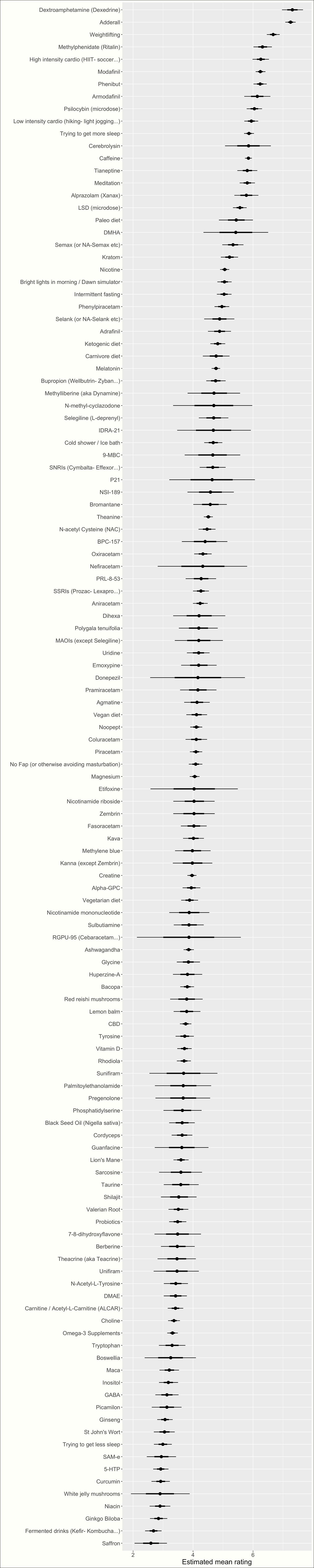

The author of the blog Troof sort of replicated my 2020 nootropics survey. But instead of another survey, they made a recommendation engine. You rated all the nootropics you’d taken, and it compared you to other people and predicted what else you would like. The end result was the same: lots of people providing data on which nootropics they liked. Troof got 1981 subjects - more than twice as many as I did - and here were their results:

This is hard to compare to my survey - it has some different chemicals, and includes a few things that aren’t chemicals at all like meditation and exercise. But the things that both surveys share are in a pretty similar order. I think we have mostly gotten what we can get out of this methodology, without many big surprises.

Why do I say this in such a resigned-sounding tone, as opposed to a more triumphant “the results have replicated, so we’re now sure they’re true”? The surveys show that:

Addictive or illegal things do better than safer ones

Difficult but popular lifestyle interventions do better than chemicals

Fancy high-tech chemicals do better than well-known normal ones

We should sort of expect all of these things to be true. People wouldn’t keep doing difficult lifestyle interventions unless they worked; the truly useless ones have probably fallen into obscurity. People wouldn’t risk addictive or illegal things unless they had impressive effects.

But it also seems kind of suspicious for placebo effects. People go through a lot of trouble to do something and then figure it must work. If something’s too cheap or easy or boring, they forget about it.

I’m especially concerned by psilocybin microdosing, which ranked 8th of almost 150 interventions. Several double-blind studies have now shown this doesn’t work (eg). Worse, in unblinded studies, it seems to “work” best for the people who most strongly believe it will work, and seems to have whatever effect these people believe it will have. This is most likely a very exciting-sounding intervention that doesn’t work at all, and it was one of the very highest-rated on this survey. Meanwhile, SAMe, which has been shown to work well in RCT after RCT, is one of the lowest-rated.

To put this another way: if you made a model combining some measure of “how hard is this chemical to obtain / how hard is this lifestyle intervention to practice?” and “how novel and high-tech does it feel?”, plus one or two other things like “is this a stimulant?”, it feels like this would predic the results almost perfectly. Does anything stand out as doing substantially worse than the simple model would predict? It really doesn’t. Maybe theanine, a little? I’m grasping at straws.

Finally, in my survey, I got impressive results for Zembrin, a certain extract of the kanna plant. This survey fails to replicate that - Zembrin lands exactly where the “how hard is it to get? how fancy is it?” model would predict, which is not very high. I’m not sure why my survey got such strong results. I know I was personally excited about Zembrin, so there’s room for experimenter bias, but I can’t think of how I would have added in the experimenter bias when I was just collecting your ratings. Maybe I bungled the statistics somehow? In any case, it’s a completely average anxiolytic in every way.

Thanks to Troof for doing this! They draw some different conclusions from me, which you can read at the end of their post.