[Original post here]

1:

This doesn't address allegations that many of California's homeless are from elsewhere, but deliberately moved to a few metro areas due to nice weather and generous social services. (Or, I've heard stories that their local town put them on a bus to SF). If .2% of the population everywhere is basically OK with a lifestyle of camping on the street and doing drugs, and then they all cluster in one area- that area will likely end up a mecca of homelessness.

Many comments made this point. Shellenberger did bring it up in the book, so its absence in the post is my fault and mine alone. He writes:

I asked experts and advocates, “How do we know that the homeless population won’t replace itself if provided with housing?” Said Randy Shaw, the Tenderloin permanent supportive housing provider, “The question you’re raising is one that never gets discussed. Somehow, there’s this sense that San Francisco is under the obligation that anyone who comes here we have to suddenly house. There is an underlying logic that San Francisco doesn’t really ever want to talk about.”

Said Chicoine, the permanent supportive housing provider for the Kushel study, “I don’t have a solution. I will acknowledge what you’re saying. I’m not going to be a bullshit advocate who says, ‘Oh you should just ignore that.’ It’s real. There’s so many stigmas and stereotypes that some of us in the industry were scared of telling the truth.”

I asked Steve Berg of the National Alliance to End Homelessness in Washington, D.C., a similar question. “Let’s say we build one hundred thousand apartment units. What’s to prevent another hundred thousand people from going from doubling-up and couch-surfing to become homeless and ask for housing?”

“That will definitely happen,” said Berg. “And it’s not ‘What if,’ it’s ‘That will definitely happen.’ If you don’t deal with the reasons people are losing their housing then the system will never be able to keep up. Communities did really well getting people off the streets but they haven’t really thought about the inflow of people.”

But the stats I found were that 70% of SF homeless lived in SF before becoming homeless, 22% were elsewhere in California, and 8% were from other states. From this report, I gather most of the Californians were elsewhere in the Bay Area or nearby, and this is more like homeless people in Palo Alto going to San Francisco because it’s the nearest big city with a shelter, rather than people opportunistically seeking places with good social services. So while the opportunistic thing does happen, it doesn’t seem to be responsible for very much of the homeless presence.

I don’t know whether the numbers are different for chronic mentally ill homeless. I could imagine these people are more likely to come out of state (more experienced in the homeless lifestyle and how to optimize it) or less likely (they don’t have the resources and executive function to plan a scheme like that).

Overall these numbers make me a little less worried about this concern. San Francisco is already quite generous, and even if some new policy doubled the absolute number of people who came from elsewhere, it would only increase the total number 10-20%.

2:

James M on Houston’s success story:

These numbers are from 2019, but you might enjoy them:

Houston Texas has reduced its homeless population from ~7,000 to ~4,000 in the last 10 years even as the metro area's population increased from 5.8 million to 7.0 million, and they did it by doing a housing-first solution that was viable and scaleable because housing costs were low. They housed 17,000 formerly homeless people during that decade (notice that 17,000 >> 3,000, so a lot of homeless people are transiently homeless). Houston's funding to homeless programs was $38 million in 2019, compared to LA's $619 million, and LA's homeless population went from ~25,000 in 2009 to ~55,000 in 2019 while the LA metro area* went from a population of 12.9 million in 2009 to 13.3 million in 2019.

So to compare those 2 cities:

Both have about 1/3 of the population of their metro area in the city proper.

Houston provides $12,700 in funding per 2019 homeless person

LA provides $11,254 in funding per 2019 homeless person

Houston's metro area increased in population by 21% in the last decade

LA's metro area increased in population by 3% in the last decade

Houston's homeless population FELL by 42% in the last decade

LA's homeless population ROSE by 120% in the last decade

It's all about housing affordability, not Texans being better about things than Californians. Dallas is struggling to get its homeless population down partially because its real estate is getting less affordable than Houston:

https://www.texastribune.org/2019/07/02/why-homelessness-going-down-houston-dallas/

Together with the model showing housing prices predicted homelessness well, I find this really convincing.

3:

Eledex from DSL wins Most Dramatic Story:

My, and my whole family's, take on homelessness has changed significantly in the last year and a half.

The lot next to my house had a giant three story tree which formed a dome around its base. Shortly after moving into my house a camp of 5 - 15 homeless people (depending on the day) moved into the tree. They yelled, fought, had fires, used power tools, and behaved in various undesirable ways. I called the police on them for various offenses ~5 times without ever having even a single officer or official appear on site. About 8 months after they had moved in (I found the backstory out in retrospect) the lot was purchased by a developer. Construction workers came and told the homeless people they should leave because the tree was being cut down tomorrow. Per said construction workers the response was "over our dead bodies, we will burn it down first!" to which the construction workers, who were planning to cut the tree down anyways, responded with a shrug. Mind you the edge of this giant tree was ~15 feet from my house. That day/night the homeless people gathered >20 propane tanks and strapped them to the tree, then lit it on fire.

I woke at ~2 am to rattling bangs shaking my house, a weird bright red glow shining through my kitchen window, baking heat emanating from the windows, and my wife and six day old child screaming. We fled the house naked with our child, injuring my wife who had just given birth. I went back in once for some documents and clothes after determining the house was not actively on fire. After maybe 5 minutes the fire department showed up and put out the fire. The next day the construction workers cut down a sooty and much reduced tree. One cop spoke to me on the phone once and never followed up. All the same homeless people still roam the area and now live in a wash ~150 feet away.

I've now moved to a fancy expansive HOA community that costs more than twice as much. I used to think homelessness was a hard problem with no good solutions. I no longer think that, I'm now in favor of basically anything that results in fewer homeless people.

This is vivid enough to clarify a few things for me.

In a perfect world, the way this would have gone is that the first or second time Eledex called the police, they would have solved the problem somehow.

In this imperfect world, Eledex is left with two proposed solutions (assuming that “just suck it up and deal with it forever” doesn’t count as a solution). First, move to “a fancy expensive HOA community that costs more than twice as much”. Second, “basically anything that results in fewer homeless people”.

This second one seems deliberately inflammatorily phrased, but I guess that’s why this seems so vivid. Eledex is saying that if the government can’t do surgical strikes on people who are actually breaking the law / harassing people, then citizens are going to demand sweeping action. This sweeping action will be unfair to some (homeless people who aren’t causing trouble), but not doing the sweeping action seems unfair to Eledex (and especially hypothetical versions of Eledex without enough money to move to the suburbs).

In other words, if we can’t solve the problem fairly and properly through competent responsive police who enforce the laws as written, then there’s going to be a lot of pain and unfairness, with the only remaining question being how to distribute that pain and unfairness among homeless vs. homeful people.

Why is it so hard to solve the problem through competent and responsive police? Years of depolicing probably haven’t helped, but also, I’m imagining being the police officer who shows up here, and - what? Eledex says “Officer, these people are generally annoying, they yell a lot and start fires and stuff”. Even if there’s a regulation against eg noise on the books, it’s probably not a regulation that allows you to call for backup and arrest fifteen people and throw the book at them. If you give them fines, I assume they will never pay. If you do take it very seriously and spend 5-to-6-digit sums of money to give all of these people a fair trial - if you make Eledex and their family come to court and testify, let lawyers for the homeless people cross-examine Eledex and try to prove that they’re racist or lying or confused about where the noise came from, and miraculously get a conviction - then maybe these people are in jail for however many weeks or months you get for noisy scary trespassing, after which they get released and come right back.

Common-sensically what these people are doing is bad and should stop. My guess is that a hundred years ago, this would have been enough to stop it, and the amount of police discretion that made this possible would also have generated a bunch police corruption and brutality and rights violations. Now nobody gets to use common sense at all, and this does sort of make the brutality and rights violations a bit less. Whatever I think of this balance, I’m not really optimistic about our current ability to solve this the perfect world way where police are responsive to Eledex’s complaints and able to deal with these people in particular, while leaving other innocent homeless people alone.

So that leaves some kind of law targeting all homeless people and demanding they go in shelters or something. I dunno, seems unfair. Probably there are gradations of unfairness and you could figure out some way to minimize the impact, but I don’t know, Eledex sure does have a valid gripe here.

4:

Sean does some excellent detective work on both my and Shellenberger’s claims. I edited some of these into the post already, so you may not have seen the mistaken versions, but here are the corrections. First, on the Zillow study:

Hi Scott. You write: "The researchers do not use the terms “local policy” or “social attitudes” in the paper itself." But in the paper it states: "To account for these unobserved local covariates, we include a CoC-level dynamic latent factor F 0 iβi,t, allowing for small departures from the cluster-level regression that may be due to local policies, cultural attitudes toward homelessness, affordable housing initiatives, and many other difficult to observe local factors." Doesn't take away from your main point, but they do mention local policy, and "cultural" attitudes seems like a reasonable proxy for "social" attitudes.

I responded “Thanks, I'll correct that! I just CTRL+Fd "local policy" and "social attitudes" and tried to skim for proxies, but seems like I missed these.”

Next, on mental illness among the homeless:

You [Scott] write:

" I cannot find this report anywhere, the methodology does not seem to be public, and when people give a link to it, it’s always to this Google document which assumes there are exactly 4000 people in this category and then breaks them down further - 100% have psychosis, 95% have alcoholism, etc. "

I think this is the report:

https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/MHR/Mental_Health_Reform_Update_Report_FINAL.pdf

And this the methodology:

"Through an in-depth data analysis, conducted in collaboration with the DPH Whole Person Care team, the Mental Health Reform team found that approximately 18,000 adults experienced homelessness in San Francisco in fiscal year 2018-19. These individuals were identified by the Coordinated Care Management System (CCMS), a DPH-operated system integrating 15 separate databases from DPH, HSH and the Human Services Agency (HSA). CCMS defines people as experiencing homelessness in the fiscal year if they either: 1) utilize a City service that indicates housing instability, for example, a City shelter, or 2) self-report homelessness while accessing health care services.

While the DPH estimate of 18,000 people experiencing homelessness in FY1819 may appear to conflict with San Francisco’s Point-in-Time Count (8,035 people counted in January 2019)1, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) details in its Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress that the full-year number is generally 2.5 times greater than the single-night count.

Using the CCMS-defined 18,000 people experiencing homelessness as the base, the Mental Health Reform team analyzed the population’s diagnostic epidemiology to understand the associated burden of behavioral health issues. The team found nearly 4,000 adults experiencing homelessness who also suffer with cooccurring mental health and substance use disorders. Specifically, in addition to homelessness, this group of 4,000 has a history of both psychosis and substance use disorder."

Shellenberger I believe makes the mistake of using the one-point-in-time number (8035) as his denominator as opposed to the CCMS number (18,000), which the authors use in their report.

This is another really good catch, and means the percent of the homeless with mental illness + drug abuse is only about 22%, not the stated ~50% - although considering only the chronic homeless separately might blunt this change.

Next, on Los Angeles’ Proposition HHH, which I (following Shellenberger) described as trying to build new houses for $100,000 but later ballooning to $500,000:

You [Scott] write:

“[Los Angeles] hoped to build ~10,000 units for the homeless, at a projected price of $140,000 each.”

This might be a bit misleading; I think Proposition HHH’s contribution of ~$140,000 was always meant to be a *partial* subsidy of per-unit costs. Here’s the text of the proposition in question:

https://cao.lacity.org/homeless/PropHHHCOC-20181109d.pdf

See page 23 of that PDF, which shows the subsidy allocation. Also if you "ctrl f" for "subsidy" you'll note other places where it's made clear.

A more readable version of the same point comes from the city’s controller, who writes:

“Funds from Proposition HHH make up only a portion of total development costs. Across all projects in the LAHD/HHH pipeline, the HHH subsidy per unit is approximately $134,000, or 23% of the total development cost of a project.”

That’s from:

https://lacontroller.org/audits-and-reports/problems-and-progress-of-prop-hhh/

You write:

“But in fact, five years later, LA has completed only 700 units, and the cost per unit has spiralled to $531,000 each. Nobody has a good explanation for what happened, with Shellenberger quoting one local service provider who said a lot of it was “bullshit costs”. “

a. On only completing 700 units, I have some evidence here from the comptroller that’s a bit more nuanced:

“the total number of completed units (1,142) is wholly inadequate in the context of the ongoing homelessness emergency”

And

“...there are almost 4,400 units in construction.”

So – about +400 on where you were (still “wholly inadequate” per the comptroller’s editorializing), but there are also thousands more in construction per the controller’s same report.

I think the ~400 discrepancy might be that the *Reason* article is from 2021, and the comptroller's report from 2022.

As to “bullshit costs,” there are a couple of other, perhaps complementary, explanations.

-One is just context from above: the HHH funds were always only meant to be a subsidy.

-Two is the city is guilty of overconfident modeling, according to the controller, and that overconfidence was taxed very heavily by the pandemic and its consequences in the construction markets. He writes:

“Even before the pandemic, a study by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that construction costs for multifamily buildings across the State were rising due to factors such as gaps in the construction workforce and higher materials costs. The unprecedented disruption brought on by the pandemic and other factors accelerated these trends. Existing labor shortages in the construction industry became more pronounced and the cost of some construction materials—such as lumber—skyrocketed. While these costs have somewhat stabilized from their record highs, they remain markedly higher than their pre-pandemic levels.”

The controller’s solution here, fwiw, is in part to reallocate much of the remaining HHH funding to “acquisition, rehabilitation, or adaptive reuse opportunities,” which seems in line with your suggestion around short- and medium-term mediocre solutions being more achievable and practical than idealistic HF-ish ones.

Hope springs eternal on that one!

On shoplifting:

1. Shellenberger’s claim is:

“Larceny, which is shoplifting and other petty theft, rose 50 percent, from roughly 3,000 incidents per 100,000 people in 2011 to about 4,500 in 2019.”

Short version is that I think he's correct, but that he complicated his correctness somewhat by describing "shoplifting" as an example of "larceny."

2. The source you show that compares Kern to San Francisco is found here:

http://www.cjcj.org/news/13219

*That* site’s source is here:

https://openjustice.doj.ca.gov/exploration/crime-statistics/crimes-clearances

And it's the California’s DOJ site. And here’s it where Shellenberger is I think on pretty firm ground, and where some of the anecdotes you’ve heard from your friends and patient *do in fact* match up with the data.

The primary challenge with the graph from your essay is that it uses only SHOPLIFTING for its comparisons. Shellenberger is talking about LARCENY (and again then complicates that somewhat by stating shoplifting as an example of larceny).

But the DOJ separates out "larceny" from "shoplifting." They are two different classifications, and have different data attached to them.

And, within that classification framework, it’s true that shoplifting follows the pattern of the graph in your essay. But larceny almost perfectly matches onto Shellenberger’s description. Source is here --

https://openjustice.doj.ca.gov/exploration/crime-statistics/crimes-clearances

-- though you will have to input "San Francisco" to check.

According to that site: There were 24,304 reported larcenies in 2011 in SF. There were 39,687 in 2019 in SF. This tracks very nicely with Shellenberger’s per 100,000 claims.

But shoplifting barely moves at all, and has very few reported incidences, as you discussed.

3. How to resolve this?

Under the CA penal code, shoplifting is “entering a commercial establishment, during business hours, with the *intent to steal,* where value does not exceed $950.”

So one guess is this is kind of “niche” charge. Once “intent to steal” becomes “actual stealing” it gets reclassified as larceny, of which there has been the steep rise that your friends have described (and which, in absolute terms, is more than 10x as common as shoplifting). That's speculation, though. What seems clearer is that Shellenberger's claim of larceny appears to be sound, empirically, according to CA DOJ.

I’m not sure I agree with Sean on this one - the site breaks down larceny into lots of different sub-crimes, and most of the rise is from car break-ins - which everyone already agrees have gone up a lot. I don’t think this leaves a lot of room for the growth in larcenies to come from shoplifting-not-officially-categorized-as-shoplifting.

And on drug use:

1. You [Scott] write:

"San Fransicko’s description of Amsterdam solving its drug and crime problems matches the other sources I found, although I’m confused about how much harm reduction was involved."

I'd dissent with your and Shellenberger's description of the trends here.

2. If you go here:

https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/en/dataset/7052eng/barv?ts=1656160323471

(That's the central bureau of statistics for the Netherlands.) It brings you to the underlying cause of death, broken out by subtopic, for the whole country.

And then if you filter "topic" by "5.2 -- due to use of drugs" you'll see a pretty steep rise in drug-related deaths from about 2012 to now.

Here's one account of many in the popular press describing the phenomenon --

3. This corresponds (at least in theory) to the more-than-doubling of homelessness in that same period.

i.e., One reasonable prior is that increased homelessness is associated with increased drug use, and that increased drug use is associated with increased deaths due to use of drugs. That seems to be borne out in the official Dutch data. As homelessness has gotten worse, so too have drug-related deaths. What I can't square is your ACS data which shows overall declining drug use. I have to look into that some more.

Overall I’m very impressed with Sean’s work here. Sean, if you ever have anything this illuminating about some other topic, please send me an email and pitch it to me.

5:

Graham shares his experience as an “ex-cop in a city with a lot of homeless”:

I can tell you homelessness is not a thing in suburbs at least in part because suburban police do not allow it. This can be achieved through a number of methods:

1) Drive/bus all homeless to the nearst big city, buying them tickets or giving them courtesy rides in the back of police cars - this is what the suburban police who bordered my beat did. It's extra effective in a place like SF where there might be a water boundary and large bridge between jursidictions.

2) Eliminate all things that would attract homeless, such as shelters/services but also open-air drug markets. Cities have these things, suburbs make sure they do not - and transients will often tell you quite specifically that they are looking for them.

3) Issue non-extraditable arrest warrants for minor crimes that transients often commit (like trespassing), which are only served if the offender returns to the suburban jurisdiction. This latter method is especially effective, as offenders know they are free as long as they stay out of the suburb, and big-city cops generally cannot serve the arrest warrant to remove the offender from the city.

I’m surprised cities co-operate in this game while suburbs defect. Why don’t cities bus their homeless back to suburbs? Why don’t they eliminate their shelters? Obviously this would be pretty anti-social, but why are the suburbs selfish in this game and the cities altruistic? Is it just that there’s so much established precedent that cities believe it’s their problem and suburbs believe it isn’t?

Also from Graham:

I can tell you [the shoplifting situation is] actually very simple. Almost all data on property crimes is garbage. Most people do not reliably report property crimes of any kind, if you look at the National Crime Victimization Survey you see only about 30% of larceny is ever reported. Shoplifting in particular is almost never reported in large cities, retail workers do not care. They don’t get paid to care, they don’t need a police report for insurance, it takes hours to get a police response, and nothing happens to shoplifters in any large progressive city anyway. I used to ask retail employees in my beat, they would always tell me about rampant shoplifting they simply didn’t bother to report. Changes in reporting caused by Prop 47, COVID and other random factors like police response time will always swamp any actual change in crime. Property crime statistics are worthless. People should believe their own eyes.

An exception: I’d say the data on auto theft is probably more reliable, because having your car stolen is a major pain in the ass that people notice, most stolen cars (unlike all other stolen property) are recovered, and insurance will not give you a whole new car if you haven’t bothered for file theft report.

I’m still confused that reporting varies in exactly the right way to keep the reported level constant regardless of the real level, but right now that’s my only objection to just going with the “stats are wrong” story.

6:

AvalancheGenesis has more on shoplifting:

I'll also add some SF retail employers now actively discourage paying any attention to shoplifting at all. Carrot: "you'll never be held responsible, even if you could have feasibly stopped the boost". Stick: "we will censor and possibly outright fire you for even minor confrontations". You can entirely forget about any sort of reporting, even to the mall cops, outside of egregious cases that involve physical injuries. But even those are more likely to be classified as assault etc instead of property crime. (Same trend discourages reporting most muggings here. Possibly a whole other anecdata minefield there. I think car break-in reporting is more accurate mostly because there's hard physical evidence which simply can't be brushed aside - plus insurance.)

The carrot further erodes labour's sense of agency and value. There's a certain freeing aspect in not having responsibilities - but if one has no actual meaningful responsibilities on the job, isn't it just make-work? The "don't care" attitude starts to creep into other areas beyond just shoplifting, creating a perceptible loss of morale and work ethic. It'd be one thing if the solution was simply passing the buck to security or middle management as the "eyes and ears", but their hands are mostly just as tied.

The stick causes additional problems beyond the shoplifting itself. Everyone in retail (ideally) comes in with a certain expectation of being treated like shit and deferring to utility monster customers. But it's above and beyond that baseline to proactively fear for one's job just in case a confrontation is subjectively perceived to have been "excessive". At my work, there's been a suspicious pattern of such firings occurring along totally coincidental racial and gender lines, further contributing to general apprehension. We've also entirely stopped stocking certain high-value items due to how often they get stolen, which isn't fair to the law-abiding legitimate customers who want them too. All to avoid potential conflicts.

Upshot: whether the anecdata or the Official CDC Statistics are more reflective of the territory, *people act like the anecdata are true*, with consequent harmful policy and behaviour modifications. So spending resources to address the perception, if not the underlying (non-)problem, would seem to be a $20 win lying on the ground regardless. Current Nash equilibrium is painful for everyone.

7:

Slaw (writes Slaw’s Newsletter) says:

I think that the canonical reference when talking about a data driven approach to the homeless problem should be "Million Dollar Murray" by Malcolm Gladwell. Gladwell cites Dennis Culhane's research on homelessness that produced a surprising outcome: the most frequent period of homelessness is a single day. The second most frequent duration? Two days.

Why? Because when you're talking about homelessness you're talking about (at least) two different populations. The first are those individuals who are homeless only briefly--they are often employed and after a night or two of sleeping in a car or on a bench they find shelter on a friend's couch or in the basement of their parents home. In Gladwell's narrative they can be ignored because they can take care of themselves.

The other population is far more problematic. For this group of individuals the average stay on the streets isn't measured in days, it's years. Rates of drug abuse and mental illness are far higher for this group than for the general population, along with the concomitant issues of joblessness and familial isolation. (Culhane in another interview said that they tend to have "tenuous" relations with friends and family. Translation: they can't stay at Mom's house because they pawned the tv to buy crack and are now persona non grata.)

This is not a distinction without a difference. If homelessness has its roots in simple economics than providing housing vouchers or subsidies should be enough to make a difference. If the real issue is addiction and mental illness than those measures will be woefully inadequate.

And Mek writes:

As someone who has, on occasion, been homeless (and being 195 cm and 125 kg and sleeping in a '99 Camry is not an experience I can recommend) and also only having read the first section, I have a feeling that there may very well be different "classes" (?) of homeless.

I will admit that I was fortunate enough to not be faced with the prospect, and fair warning, this is basically just "gut feeling" levels of rigor, but I simply feel that there is likely a distinction to be made between "people who are currently homeless because they lost their housing due to recent misfortune or price increases" and "people who are currently homeless and shoot drugs and defecate on the sidewalk". To call back a few weeks, just describing all of these people as "homeless" strikes me as akin to (and likely as effective for "solving the problem") as calling everyone from the person with mild Aspergers and the truly severely 24/7 care require disabled person with autism, "Autistic".

"Homelessness is a spectrum", etc.

And perhaps I am absolutely, completely wrong, and I might well have also ended up using the sidewalk as a restroom and doing hard drugs if it had gone on longer than it did. I'm also probably significantly more able to quickly find *some* job doing *something* that pays decently than your average homeless person, and thus that may also color my views on the topic.

I don't know, and hell, maybe you even address all of this in the, uh, 90% of the article I haven't actually read yet, but it seems as though simply trying to treat this as a monolithic problem isn't going to actually be effective.

I dunno. I understand that you disagree with Shellenberger about the "drugs and mental illness" driving factor versus housing costs, but... why couldn't it be *both* in this case?

That is to say, yes, the general levels of homelessness in SF may well be primarily driven by housing prices. But perhaps the thing that makes SF seem so particularly bad is the proportion of the homeless population there with a serious addiction and / or mental health issue. (Epistemological status: Total ass-pull. I have no research or numbers to back any of that up, I'm basically just brainstorming at this point.)

MadmanB says the same:

Some thoughts below. My background: SF Bay Area resident for 20 years, frequent visitor for 10 years before that. Spent 3-4 years from 1998-2003 doing weekly food distribution to homeless in southern California.

There are (at least) three "sub-classes" of homeless and confusing or conflating them results in total confusion regarding solutions.

A. Subclass A are the "lifestyle homeless". Vagabonds, drifters, gutter punks, street musicians, beach bums, craft stall vendors, "van lifers". A number of these folks I know by name, and consider to be friends. They could hold straight jobs in theory, and often come from more conventional backgrounds. The tradeoffs inherent in living the straight-and-narrow are too much, and they cannot or will not do it. Sometimes drugs and mental illness are an issue, but not overwhelmingly so.

B. Subclass B are the "down on their luck homeless". Living in car, van, or RV temporarily due to job loss, bills, bad luck, or poor choices coupled to above. Will actively seek out shelter, come to social services and adhere to plans to improve the situation. Aiming to get back on their feet. Overwhelmingly working class and not happy or proud of their current condition.

C. Subclass C are the "wretched homeless". Sorry about the moniker but it fits. Extreme mental illness or drug addiction. Limited ability or agency. Suffering in many dimensions. Selling body for drugs. Crime and violence -- both perpetrators and victims. Passed out on street in own fluids. These cases are extremely sad, and my heart breaks for them. A test: if you ask them their name or their story, you most often cannot get any kind of comprehensible reply.

The wretched homeless are the ones that are most obvious in many ways, and seemingly what the book focuses on. They will not be helped by marginal changes in housing markets: rents dropping from $1500/mo to $1250/mo are not their issue. On the other hand, the "down on their luck" *WILL* be helped, and mightily so, by more affordable housing and/or social programs. NIMBY and 30 years of working class job offshoring are reasonable causes.

Class C cannot be divorced, in any way, from changes in mental health policies, nor from the flood of ever-stronger drugs in the last decade. Drug induced psychosis and/or willingness to do almost anything for the next hit create a massive hole that is very very very hard to pull out of. Many (most?) die in that condition. Jail seems to be the only circuit breaker we have in the current system, and it does a poor job of interrupting the cycle.

In the 30 years of my experience, the problem in SF Bay has gotten much worse. Some areas have improved (as I recall Mission district was very intense with heroin on the street in the 90s). Both classes B and C seem to be much larger overall.

A major concern is preventing lifestyle and down-on-their-luck from becoming wretched. That is, how can we stop class A and B from becoming class C? Another major concern is tailoring programs and help to fit the person. A wretched homeless selling their body and dignity for the next hit is NOT going to fill out your paperwork, and will scare or harm others in a shelter.

I think this review is too hard on Shellenberger. He seems to grasp realities of the problem that are glossed over by the homeless-industrial-complex.

This is a really good and really important point, and one way I worry I was being unfair to Shellenberger’s thesis. I think there were a lot of cases where he said “the homeless are mostly X”, I found statistics showing most of the homeless weren’t X at all, and what he really meant was something like “the homeless I really care about who are causing all the trouble are mostly X”.

(for example: as discussed above, most homeless people are natives of the city they’re in - is this also true of most homeless people weighted by number of problems they cause? Homelessness seems very correlated with/responsive to housing prices; is this also true of number of problem homeless?)

Unfortunately, you can’t ask people on a survey “are you the good or the bad kind of homeless person?” so there aren’t a lot of statistics that do a good job taking this into account.

One possible criticism of San Fransicko is that it makes a good and valid criticism which statistics will naturally contradict because everyone’s doing the statistics wrong, and instead of arguing this, it tries to massage the statistics.

8:

David Roman (writes A History Of Mankind):

As somebody somewhat familiar with the Portuguese situation, and who was born next door to Portugal and has lived in the neighborhood for a long time, let me clarify that Portugal is NOT a very conservative country, not even when it comes to drug use. In fact, it's so not conservative that the usual party switcheroo between conservatives and progressives there literally involves the "social-democratic party" running against the "socialist party" since the early 1970s. In fact, the only actual conservative who was ever president of Portugal in living memory was murdered by state security; they didn't even bother to cover the crime very much, and then the whole country has sort of ignored the matter for decades, as one of those things that sometimes happen https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_de_S%C3%A1_Carneiro. Regarding the specific issue of drug use in Portugal: we should mention this study https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31808250/, and put it in whatever context. It looks into all hospitalizations that occurred in Portuguese public hospitals from 2000 to 2015, and finds that the number of hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of psychotic disorders and schizophrenia associated with cannabis use rose 29.4 times during the study period, from 20 to 588 hospitalizations yearly (2000 and 2015, respectively) with a total of 3,233 hospitalizations.

Without wanting to claim that Portugal is fundamentally conservative, it does seem to have always had fewer drugs than the average European country. If I’m wrong about that, let me know.

9:

Shaked Koplewitz writes:

Based on these excerpts, I think you're wrong to describe his position as "supporting sweeping institutionalization" - he supports more institutionizing than we have now and thinks we've gone too far to the other side, but doesn't seem to support peak institutionalization (there's a pretty wide gap between what we have now and the My Brother Ron era). When you say "sweeping institutionalization" I imagine "immidiately rounding up all the homeless people and locking them up". His described preferred policy has the option for that for some people, but unless I'm significantly misunderstanding it it's not the default for everyone (I don't think the Netherlands has mass institutionalization?).

I didn’t want to say that Shellenberger “supports institutionalization”, because almost everybody (including existing laws) supports some institutionalization, and the position I’m criticizing is supporting much more. Maybe I should have said he supports “much more” institutionalization rather than “sweeping” institutionalization, I guess.

I would be more sympathetic to this fair criticism if he was more willing to criticize the mass institutionalization era and less willing to criticize everyone who was ever against it.

10:

Lots of people wanted to tell their horror stories. Daniel Franke:

Have you ever tried reporting a robbery or an assault in San Francisco? I have — tried, that is — twice. The third and fourth times I didn't bother trying. The fifth time I just got the hell out of San Francisco. I have a friend who got literally curb-stomped, has it on video and has the identity of the guy who did it, and eventually gave up on getting anyone to take his report after getting a jurisdictional runaround. The real crime rate is something much higher than the official statistics.

And Alice K:

I appreciate your trust of in-person reports about shoplifting. We live part-time in Seattle. We do see flagrant, open shoplifting, where the thieves just wheel out carts of stuff in front of security guards. This is a new thing. We asked why the guards don't stop it and they say a combination of the risk of crazy, violent response combined with no legal consequence is why. I guarantee most of it is not being reported. The remaining police are overwhelmed. Unless one is filing an insurance claim and a case number is required, there is no point in calling them to report theft. It is a waste of time.

11:

Unsigned Integer and several other people thought Phoenix/SF comparisons were unfair:

I wouldn't be surprised if Phoenix and Houston had few unsheltered homeless people because it was too hot to live outdoors. The human body doesn't have an air conditioning system (only evaporative cooling through sweat). So, if the temperature outside is above the range of normal human body temperatures, you *will* get heatstroke eventually, it's only a matter of time.

California and Seattle are among the rare US cities where it never gets unbearably hot or cold, and do have a lot of homeless people. But cities in Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina also have okay climates without too many homeless, so I’m not sure how much to update on this.

Unsigned also links to r/homeless, which is pretty fascinating and a good antidote to the temptation to think of all homeless people as crazy or dumb or addicted - though it also includes threads like San Francisco is the ultimate place to camp.

12:

Gordon Tremeshko writes:

Apart from the spiraling costs, which you correctly noted, have we forgotten so quickly what happened with the public housing projects built with Great Society money back in the '60s? To take one famous example:

Unlike many of the city's other public housing projects such as Rockwell Gardens or Robert Taylor Homes, Cabrini-Green was situated in an affluent part of the city. The poverty-stricken projects were actually constructed at the meeting point of Chicago's two wealthiest neighborhoods, Lincoln Park and the Gold Coast. Less than a mile to the east sat Michigan Avenue with its high-end shopping and expensive housing. Specific gangs "controlled" individual buildings, and residents felt pressure to ally with those gangs in order to protect themselves from escalating violence.

During the worst years of Cabrini-Green's problems, vandalism increased substantially. Gang members and miscreants covered interior walls with graffiti and damaged doors, windows, and elevators. Rat and cockroach infestations were commonplace, rotting garbage stacked up in clogged trash chutes (it once piled up to the 15th floor), and basic utilities (water, electricity, etc.) often malfunctioned and were left in disrepair.

On the exterior, boarded-up windows, burned-out areas of the façade, and pavement instead of green space—all in the name of economizing on maintenance—created an atmosphere of decay and government neglect. The balconies were fenced in to prevent residents from emptying garbage cans into the yard, and from falling or being thrown to their deaths. This created the appearance of a large prison tier, or of animal cages, which further enraged community leaders of the residents.

...

While Cabrini–Green was deteriorating during the postwar era, causing industry, investment, and residents to abandon its immediate surroundings, the rest of Chicago's Near North Side underwent equally dramatic upward changes in socioeconomic status. First, downtown employment shifted dramatically from manufacturing to professional services, spurring increased demand for middle-income housing; the resulting gentrification spread north along the lakefront from the Gold Coast, then pushed west and eventually crossed the river.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cabrini%E2%80%93Green_Homes#Problems_develop

Someone want to point me to why something like this wouldn't happen again? Keep in mind that SF already spends a 100 million to clean feces off the streets (only semi-successfully, at that). Frankly, this seems to me like an marker of what Tyler Cowen calls The Great Forgetting.

Matthew responds:

You gave a long list of problems, and it sounds like it was a miserable place to live, and it hindered economic development for some of the surrounding area... but even the later parts of the wikipedia article you link note how the residents considered it preferable to being homeless (their likely fate without it) and lobbied to keep it standing. I don't know, suppose we did it again and everything happened exactly like it did before, but also 15,000 people had a stable home they could call their own for a few decades (no matter how ill-repaired and unpleasant) instead of being homeless. I think whether that was a success or failure would be a matter of analysis, not obvious, and of comparing against alternative ways the money could have been spent. And maybe with some "lessons learned" everything wouldn't happen exactly the same and there could be an iterative improvement.

13:

Alexander Turok writes:

Suppose you came upon a small town of 600 adults. The mayor tells you that while the large majority of the town's people are kind and decent, 6 of them are complete scumbags who just have to be locked up or else the town would be in flames. Everyone knows everyone, and he can personally vouch for this being true, he says. Does this seem like a mass incarceration crisis?

What if it were 2 million, in a nation of 200 million adults?

This is a great thought experiment / example of a cognitive bias / whatever it is. I find myself sharing his intuition: if 6 people were locked up to “clean up” a town of 600, this would seem unfortunate but basically fine, but when it’s 2 million in a country of 200 million, then it feels like a crisis. I’ll have to think about this more.

14:

Cups And Mugs writes:

Claim 3 and the Interlude seem to be very poorly performed/tried seriously by cities and fall into the 'anything can be done badly' camp of approaches.

Hotels are obviously dumb and are the opposite of 'Housing First' in that they come with lots of conditions to the point that people felt like they were in prison being there. That sure sounds like conditional help to me if you have to accept prison like conditions before you accept housing. Housing First is said often, but they are empty hollow words almost everywhere. Shelters and hotels and other prison like environments are highly highly conditional and nothing like the free conditions which those in regular housing experience.

Building new buildings or finding ways to concentrate the homeless into hotels and such are all really bad ideas that are obviously bad and had bad outcomes. No surprises there. Newsome tried nothing and now he's all out of ideas! Go figure!

Taking approaches like trying a long term plan to solve 1/3 of the problem and never finishing it due to what was probably corruption and cost disease in construction...is also a really bad idea with obviously bad outcomes. Again, another non-surprise bad faith attempt which succeed in loading up their corrupt construction friends. Help the poor? How about a handout to the rich instead? It didn't work? Colour me surprised.

The label on the sticker might say 'Housing First' but as you noted...none of these cities have tried you know... ACTUALLY provided housing for all of the homeless people at the same time and in an immediate sense with no conditions which did not concentrate them in their own ghetto. Who knew it was tough to get to sleep in a hotel room or a shelter or a crappy apartment when all of your neighbours are crazy and howling and screaming all night every night?

The clearcut and obvious easy solution of just renting large numbers of apartments which are NOT clustered together idiotically to create horrible high concentration brand new sudden ghettos around hotels or housing developments....is the obvious thing everyone says they want to do which somehow has NEVER happened!!!?!?!?

We had one idea, so we tried it out badly in half-baked ways over and over again for 30 years and it didn't' work. So the original idea was never actually tried? Yep!

It makes me think...all those bad people who want to do bad things to set goals, barriers, and whatever are real and the NIMBY triggering dumb concentration ideas and half-measures don't even begin to count as real Housing First initiatives.

Does housing solve why someone became homeless or what happened to them while they were homeless or their health or drug problems? Of course not, we don't need studies for this! How can smart people talk themselves soo stupid that they think 4 walls and a roof might impact health or addiction? Those are their own problems with their own solutions, but stable housing and getting people fed and off the streets is a LOT better than having them on the streets!

Do we want to solve homelessness or not? The answer is staring us in the face, everyone pretends they are doing it already, and yet in no place has it actually been tried on 100% of the entire homeless population in an even halfway decent attempt.

I really hope one of those mayors wins and uses 3% of the city budget to end homelessness overnight. Or at least give the real housing first approach a fair go.

When I see 7,000 flats rented for 7,000 formerly homeless people in SF, then we'll see if housing solves homelessness....or at least the crisis aspect of it being really bad, obvious, and annoyingly in the fact of CBD workers and Tourists. Spoiler! It does work and very few people will choose to sleep on the street if they have an apartment, though a small number will or will some of the time as their transportation and pan handling tactics are not solved by housing either.

In fairness to the Governor, the hotels were mostly an emergency pandemic measure that everyone acknowledged was bad. But I agree I would like to see an explanation of why this hasn’t been tried. My guess is normal landlords refuse to rent to the homeless, but I’d like to see someone in the city government explicitly say that they tried this and it was true.

If the explanation is “we think it would be unfair to normal poor people who have to work hard for housing” then I would like the city to say this, instead of talking about Housing First and making everyone wonder how things keep going wrong.

15:

Bob Jacobs writes:

One small thing we could do to prevent people from becoming homeless in the first place is giving people an attorney at housing court. Right now landlords hold a lot of power over their tenants since a lot of them simply can't afford to fight injustices in court (and since court battles are publicly registered going to court could cause you to have trouble renting new homes, even if you win).

This has been the opposite of my experience (and the experience of some friends with experience here who I talked to). The stories I hear are all about how nightmare tenants don’t pay rent for months or years, smash everything in the apartment, and when landlords try to get rid of them the courts just say they won’t evict them because making people homeless is mean. The stories I’ve heard are that a lot of landlords straight out try to figure out how to avoid renting to poor people because if their tenants ever choose to stop paying rent it’s several years of nightmarish court cases to get 50-50 odds of the government ever doing anything.

So I take the opposite position here: if the government wants people to be able to live in places long-term when they don’t have the money to pay, they should give those people rent vouchers, or pay the landlord directly, or something - not invent a legal doctrine which is basically “if people don’t want to pay you then you still need to provide the service indefinitely” and give people as many lawyers as it takes to enforce that.

16:

Will (writes My Bookshelf Runneth Over) says:

I have told my left-wing friends for years that fixing American urban dysfunction (crime, public nuisance, garbage everywhere, etc.) would be a big step forwards in fighting climate change.

Why would people take public transit when people are consistently disruptive?

In this context, San Fransicko strikes me as an immensely useful and mostly accurate corrective, and any minor factual issues are unimportant.

I mostly agree. I think this is a book that makes many good points, but gets bogged down by its choice to be kind of data journalism-y, and then having to claim (mostly falsely) that there are clear statistics and stories that support its prescriptions.

If I had to rewrite this, my main changes would be:

Explain the point (mentioned above) about how “homeless” conflates beach bums, down-on-their-luck poor people, and the severely mentally ill. Claim that the first two groups are only temporarily homeless and don’t bother anyone, and that all the problems people consider linked to homelessness are caused by the severely mentally ill. Then acknowledge that most statistics collected “about homeless people” superficially don’t support your narrative. The stats say the main cause of homelessness is housing affordability. The stats say most homeless people aren’t mentally ill or addicted. The stats say most homeless people come from the area they live in and haven’t been attracted by better handouts. The stats say most homeless people do well when given housing. Acknowledge all of that is true of the three-groups-together population, but that you still think if you were to separate out the severely mentally ill group who are actually causing the problems, the picture would look less rosy.

Explain that crime statistics don’t show any rise in shoplifting, but that’s probably because shoplifting is going unreported (and has been going more unreported over time in proportion to how much it grows over time? I’m honestly still confused by this)

Explain that the 1950s system of institutionalization was genuinely pretty terrible in a lot of ways, that the people who campaigned for it to be ended had lots of good points, but that the current system is also failing people. You support some specific loosening of the current laws around commitment, and the way you would ensure that people’s rights are still respected is [some paragraph that demonstrates you have thought about this question for five minutes].

Shift the “here’s why this is morally good” argument slightly away from “this would help homeless people get back on their feet” (which I think is harder to justify as true) and more towards “this would help poor people in cities and potentially lessen NIMBYism”.

I don’t think any of these things would detract from the book’s main points, and I think they would make it much more accurate and defensible against pedants like myself who care a lot about which statements are actually true.

17:

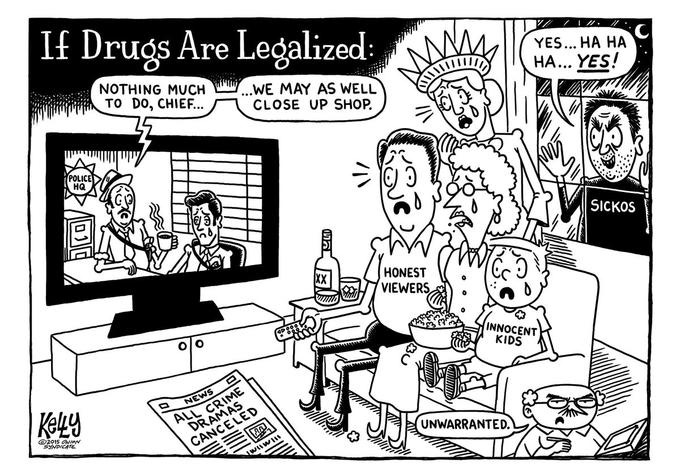

Miss M writes:

Great post scott, read all of it even though I live on the other side of the world. My only problem is the book's name: it always makes me think about that meme with the "sicko" standing next to a window going "ha ha ha! yes! yes!". It was kind of distracting.

In fact, the origin of the meme was a comic about exactly this topic:

Share this post