Highlights From The Comments On Boomers

...

[original post: Against Against Boomers]

Before getting started:

First, I wish I’d been more careful to differentiate the following claims:

Boomers had it much easier than later generations.

The political system unfairly prioritizes Boomers over other generations.

Boomers are uniquely bad on some axis like narcissism, selfishness, short-termism, or willingness to defect on the social contract.

Anti-Boomerism conflates all three of these positions, and in arguing against it, I tried to argue against all three of these positions - I think with varying degrees of success. But these are separate claims that could stand or fall separately, and I think a true argument against anti-Boomerists would demand they declare explicitly which ones they support - rather than letting them switch among them as convenient - then arguing against whichever ones they say are key to their position.

Second, I wish I’d highlighted how much of this discussion centers around disagreements over which policies are natural/unmarked vs. unnatural/marked.

Nobody is passing laws that literally say “confiscate wealth from Generation A and give it to Generation B”. We’re mostly discussing tax policy, where Tax Policy 1 is more favorable to old people, and Tax Policy 2 is more favorable to young people. If you’re young, you might feel like Tax Policy 1 is a declaration of intergenerational warfare where the old are enriching themselves at young people’s expense. But if you’re old, you might feel like reversing Tax Policy 1 and switching to Tax Policy 2 would be intergenerational warfare confiscating your stuff. But in fact, they’re just two different tax policies and it’s not obvious which one a fair society with no “intergenerational warfare” would have, even assuming there was such a thing. We’ll see this most clearly in the section on housing, but I’ll try to highlight it whenever it comes up.

I’m in a fighty frame of mind here and probably defend the Boomers (and myself) in these responses more than I would in an ideal world.

Anyway, here are your comments.

Table Of Contents:

1: Top comments I especially want to highlight

2: Comments about housing policy

3: ...about culture

4: ...about social security technicalities

5: What are we even doing here?

6: Other comments

1: Top Comments I Especially Want To Highlight

…

Sokow writes:

[The anti-Boomer] take has been imported in part from the EU + the UK where the pension system is not the same. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_Pension_(United_Kingdom)#Pensions_Act_2007

There is a lot of similar things in France that I could dig up, such as all attempts to tax benefits being defeated.

Many Europeans chimed in to say this, including people whose opinions I trust.

I find this pretty interesting. We all know stories of American opinions infecting Europeans, like how they’re obsessed about anti-black racism, but rarely worry about anti-Roma racism which is much more prevalent there. I’d never heard anyone argue the opposite - that the European discourse is infecting Americans with ideas that don’t apply to our context - but it makes sense that this should happen. I might write a post on this.

Kevin Munger (Never Met A Science) writes:

Hating Boomers (and talking about hating Boomers) is uninteresting and I agree morally dubious.

But it is *emphatically* false that “Boomers were a perfectly normal American generation”. They have served far more terms in Congress than any generation before or since (and we currently have the oldest average age of elected officials in a legislative body IN THE WORLD other than apparently Cambodia), they have dominated the presidency (look up the birthdate of every major party candidate since the 2000 presidential election...), they controlled the commanding heights of major companies, cultural institutions (especially academica).

They are a historically *unique* generation, for three intersecting reasons: 1. They are a uniquely large generation 2. they came of age as the country and its institutions were maturing 3. they are sticking around because of increased longevity. These are analytical facts, and they produce what I call “Boomer Ballast” -- a concentration of our societies resources in one, older generation that increases the tension we are experiencing from technological innovation. Our demography is pulling us towards the past, the internet is pulling us into the future, and this I think is the major source of the anti-Boomer frustration.

On the specifics of social security and why we might think Boomers have played things to their advantage (not bc they’re specifically evil but bc they have the political power to do so) -- the key thing is that they have prevented forward-thinking politicians from fixing the inevitable hole in social security that comes from our demographic pyramid. It would have been relatively painless to increase the rate or incidence of the social security payroll tax at any point in the past 25 years, the looming demographic cliff was obvious and the increased burden could’ve been shared more equally. Instead, they prevented reforms and all of the fiscal pain from demographic shifts will be borne by younger generations.

I agree this is a strong argument, and part of why I think it’s helpful to separate the three points I mentioned at the beginning.

RH writes:

We [Boomers] did [vote for ourselves to pay higher taxes and get fewer benefits]. My lifetime SS benefits will be 20-25 percent less than they would have been under previous law, and I voted for that. My SS tax rate went up itself, and has been well over 15% since the changes took effect, and the cap on earned income subject to that went up a lot. And I voted to accept all that because it was projected to be sufficient.

Then the immigrant haters decided we needed fewer workers in the country, or at least fewer paying SS taxes, so they slowed legal immigration and pushed illegals into the underground economy, so they don’t pay taxes to support social security. And social security is going to get whacked again, plus the evils the SS system was intended to alleviate -- people too old to work and too poor to live -- will return.

I think this says something profound about politics. The problem is less that there’s some group of people who don’t believe in fairness, but that fairness is very hard to calculate.

Suppose RH is right (I haven’t checked), and that Social Security would be sustainable with lots of immigration. Then whether Boomers are paying “their fair share” or not depends on whether immigration is good or bad (a hard question!), and on whether we think of high vs. low immigration as the natural unmarked state of the universe (such that immigration opponents must “own” closed borders and compensate the losers), and on what kind of compensation the losers from closed borders deserve.

Someone else commented by saying we could solve all of these problems without inconveniencing either the Boomers or the young by just increasing taxes on a few ultra-rich people. The ultra-rich could reasonably say they didn’t create this problem and it’s unfair to tax them for it. But so could the Boomers and the young! So whose “fair share” is it?

2: Comments About Housing Policy

…

James (Enriched Jam Sham) writes:

Probably most of this is true, but there is one point I would take issue with, concerning the idea of “sitting on assets not being used for market labor.” This kind of does seem like an issue, or something? And I agree one should not expropriate too many assets from boomers in order to impoverish them, or anything, but if there is a group of people with a large number of assets not being employed productively, there _is_ an issue there, right? (I think this belief is downstream of a lot of leftist anxiety about the superwealthy, though of course in general they are employing those assets productively). More of an issue if those with fewer assets are being taxed in order to provide “what is owed” in some abstract sense to those who are already not employing assets productively.

Were I old, I think it totally would be reasonable to say “You can live in a 5-bedroom house, but since you’re just a married couple these days, probably it’s better if you get by with a 3-bedroom, and probably it doesn’t need to be so central to the city, unless you can afford it. We are going to raise taxes higher.” And to means-test social security payments to some extent (phased in, over time)? Or is that going too far in my demagoguery?

I answered that I agree there’s an argument for forced house downsizing. But I also think we’re the types of people who the Right calls rootless cosmopolitans, and that people with more attachments might not be so amenable.

My grandparents-in-law built significant parts of their house with their own hands, and lived in it for ~50 years. They planted saplings in the garden and lived to see them become trees. They know the neighbors and probably knew the neighbors’ parents before them. Their daughter, my mother-in-law, lives a few blocks away. When I last visited, they could show me their son’s old bedroom, their daughter’s old bedroom, and the bedroom where their granddaughter (my wife) used to stay with them. Until recently, my grandfather-in-law was cognitively about 70% there, to the point where he could live on his own - but only through having a very predictable routine, knowing where everything was, and being in an ultra-friendly and familiar environment. Their area has now skyrocketed in cost.

I can see your side of the argument - but I also can’t blame them for being against some hypothetical policy that would force them to move to a strange apartment in the nearest affordable town 50 miles away far away from their only family/caretakers so that some striver DINK couple could turn their spare bedroom into a gym.

James answered:

Sure, I mean it wouldn’t be some sort of forced movement, it’d be more like higher property taxes. If you can afford it then that’s fine, don’t think we should do some centralized planning boomer hatred. And it should hit everyone equally. It’s just about measuring productive use of houses. But it would end up falling hardest on boomers (fortunately or unfortunately, depending on one’s perspective).

But this is maybe more reasonable as a policy idea than “lynch the boomers” which is perhaps the bailey you’re arguing against. I don’t want to be the motte, just this is (I think?) an actually good policy.

I responded that yeah, I understand it’s just higher property taxes, I’m saying there’s no way my retired and slightly-demented grandfather-in-law could afford normal property taxes on his house he bought in what was basically farmland in 1970 but which has now grown into a desirable California college town. He’s been coasting off whichever California proposition it was that says old people’s property taxes don’t go up while they own the home.

(although age has taken its toll and he now lives in a nursing home, so this is more of a hypothetical example drawing inspiration from a real situation)

James answered:

I don't mean to sound heartless, but like, every policy has bad outcomes and good outcomes. Of course with housing policy the core issue is that bad outcomes for those already there are salient, and for those not already there they are much less so. I mean my grandparents have had similar issues, I agree there would be pain. It's just about finding the right balance on the margin. But individual stories shouldn't necessarily guide policy-making (I mean "plural of anecdote" etc etc, but you see what I mean?). I am sorry about your granddad in law though, dementia sucks.

I said that I agree with this, and it still might be good on net, I just can’t bring myself to hate Boomers for opposing it.

I still think that instead of facing these tough tradeoffs, we should just build more housing, and that every person who we force to make these tradeoffs is in some sense a policy failure, even if we take the right side of them.

And I feel nervous because I’m neutralish on something where there’s basically a unanimous consensus of smart people (they all hate Prop 13), but to me it does seem to make sense that rising house values shouldn’t be able to make your current home unaffordable - both because as someone in a state where house values have pentupled in a generation this seems like a recipe for constant forced upheaval, stress, and destruction of families/community, and because it gives NIMBYs one more reason to oppose density (if someone upzones your area, that increases the value of your land, and therefore your property taxes, and might force you to leave your house - therefore, you should fight upzoning unless you want to be forced out).

Chris writes:

A halfway house solution to this is to increase property taxes but make them payable on death/sale. It has less of an effect of actually forcing people out, so the allocation effect isn’t as strong, but it would encourage people to move at the margin. e.g. those who want to free up equity, without penalising the “asset rich, cash poor.” It’s just about the only wealth tax that works, and those gains are largely CGT exempt.

This is usually discussed in a UK context as we don’t have percentage property taxes, and this is a potential way of introducing them, given in some places nominal values have 10x’d.

Huh, I hadn’t heard this before, and I like it!

Mariana Trench writes:

I genuinely don’t want you to take this personally. When you or someone over on Slow Boring starts speculating about how I, a young boomer, should be forced out of my nice house that I bought with my own money, it truly makes me want to get a gun and shoot you. Scott, I’m not going to do that, so please don’t ban me. I’m explaining how murderously angry it makes me feel. So every other age group gets to have whatever goods and services are available at a market rate, but old people have to move to shitty apartments because we’re worth so much less than young people?

I will take every legal means at my disposal to prevent you from doing this. I will block you in the courts, I will vote for evil totalitarian bastards if they support my property rights, I will seriously do anything to keep you from patting me on the head and telling me to move on because I suddenly don’t have a right to my own house, because some younger person suddenly wants it.

Several people made something like this argument, but I think it’s based on a (understandable) misunderstanding.

The policy that most people in James’ camp are proposing is to repeal California Proposition 13 (or other jurisdictions’ local variants) which lock property taxes to the value of a house when it was bought (rather than the value now). This benefits old people, who might have bought their houses 30 years ago when prices were much lower. Repealing it, and making everyone pay property taxes based on the current price of their house, would incentivize (in some cases, force) old people to move to cheaper houses.

If you treat the Proposition 13 regime as natural, then this is an attack on old people’s rights. But Proposition 13 was only passed in 1978, and plenty of states have no local equivalent. If you treat the pre-13 state of affairs as natural, then 13 is an attack on young people’s rights, and repealing it merely restores the proper fair state of the universe. This is another of those marked vs. unmarked things.

I agree that a lot of the talk around this sounds kind of ethnic-cleansing-adjacent, but nobody has the right to artificially-depressed property taxes.

3: Comments About Culture

…

WoolyAI writes:

I think this oddly dodges the two big complaints about boomers.

One, not mine but it needs to be addressed, is housing. There’s no end of content online about boomers and housing, no need to reiterate, I’m just surprised not to see it referenced when it (to me) seems such a large part of the discourse.

The second is that the boomers engaged in a lot of...social transformations that were very good for them and had really bad effects on subsequent generations and the boomers refused any limiting factor.

The best example is probably dating and “sexual liberation”. The best of all dating worlds is to grow up in the 1950s, when everyone is strongly habituated to forming stable marriages, then be given the opportunity to defect out and have tons of “free love” in your 20s, then settle down in your late 20s into a stable relationship because, well, all your peers came from stable families with strong marriage norms and 3-7 years of “free love” isn’t going to overcome that cultural background. Once the next generation rolls around and gets raised in a “free love” culture, though, rather than the stable marriage norms of the 50s, marriage starts to break down. It doesn’t take much to notice how horrific modern dating is yet it’s worth noting that even by the 80s it was obvious that something was wrong; divorce was skyrocketing and Gen X got hit hard.

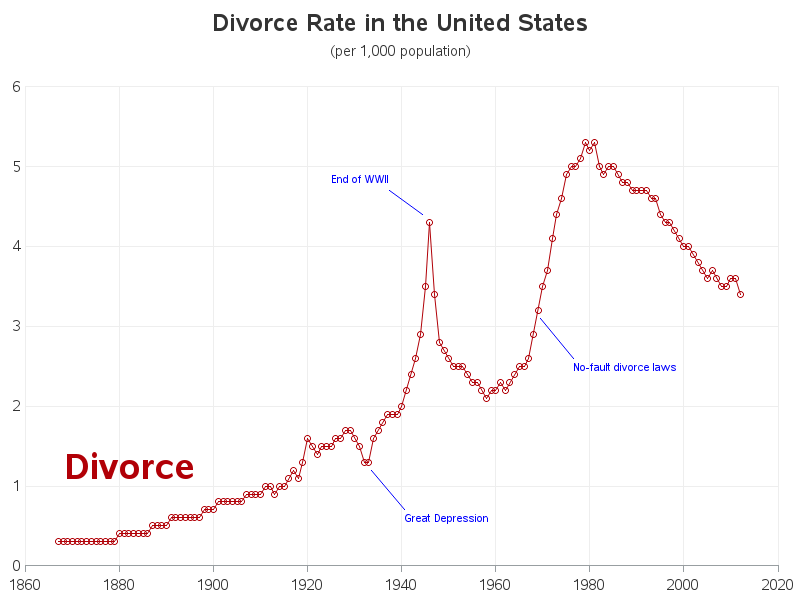

This seems false to me. Divorce rates peaked in 1980. It wasn’t Generation X (people born in after 1970) who were getting divorced in 1980 - it was Boomers themselves.

People tend to imagine the divorce trend as being about hedonist swingers trying lots of free love, but I think this is imaginary. My impression is that it’s more about moving from a regime of naively/romantically marrying your high school sweetheart, discovering later that he was emotionally unavailable and abusive and you hated him, but sticking around anyway “for the children” - to a new regime of unromantically optimizing for a compatible partner no matter how long it takes.

Boomers ended up right in the middle of the regime change - they married their high school sweethearts, then were told it was unacceptable to have an unhappy marriage - and so suffered very high divorce rates during the transition period. Everyone after them got the new regime from the beginning and never married their high school sweetheart in the first place (unless their high school sweetheart was unusually compatible with them).

I think that the people scorning the Boomers for their hedonistic free love ways wouldn’t like being married to an emotionally unavailable and abusive partner who they hated any more than the Boomers did. An alternative framing of this - not exactly correct, but I don’t think the anti-Boomer one is exactly correct either - is that we should be grateful to the Boomers for ripping off the Band-Aid in their generation and suffering the negative consequences, rather than kicking the can down the road and leaving us to be the ones who got the explosion of divorce.

In practice I doubt they had a choice either way - I think it was an artifact of changing economic conditions, especially women joining the workforce and getting more independence.

Hal Johnson (Hal Johnson Books) writes:

It’s probably a bad idea to hate a whole generation, but I will say a couple of things against Boomers.

I once wrote a piece on Stand by Me pointing out that the movie is about a Boomer who went on a grand adventure and yet won’t let his own kid bike to the pool. Anyone growing up under a Boomer hegemony had to have been aware of this, the feeling that Boomers were pulling doors shut behind them and then celebrating the beforetimes, when the doors were open. “When I did drugs it was so cool, but you better not do drugs.” “I hitchhiked across America to see the country, but hitchhiking is bad and fortunately illegal now.” If you went to school at a certain time, or worked at a certain time, you were guaranteed to encounter a teacher or coworker who claimed to have been at Woodstock (ha!) and who expressed contempt at you, the young, for not having been at Woodstock. It was weird and also really grating!

Boomers suffered a tendency to self-mythologize, and it never ends! Remember that Boomer-centered bank ad from a few years ago: “A generation as unique as this deserves a bank etc.”? Boomers were the first generation to have and be an identity (broadly across the whole US at least). This isn’t even their fault, as the identity was invented by marketers to sell pop records, but Boomers fell in love with the idea.

It’s hard to hate the Greatest Generation, not because they were great (whatever) but because someone outside their generation declared them to be the Greatest. When Leonard Steinhorn wrote The GREATER Generation about how amazing Boomers were, he did it because he, a Boomer, wanted more credit. Look at me! Look at me! There have been so many years of Look at me!

I like to watch old sitcoms from the ‘80s, and it is hilarious how much Boomer indulgence goes on. Murphy Brown reminiscing about her time in “The Revolution.” Howard Hesseman on Head of the Class kicking Dan Schneider out fo class for making irreverent jokes about the ’60s. Kate from Kate and Allie forbidding her daughter from dating a boy who didn’t support ’60s peace protesters. Just watch the opening credits of Family Ties—it’s like a nightmare!

But I bet it was fun to be a Boomer.

Vijla Kainu writes:

You forgot to mention another transformation that hurt people who weren’t able to plan for it nor did they have time to pivot: the boomers shipped their parents off to old people’s homes and defected from the compact where your parents take care of you when you’re young and you do the same when they get old and frail. Boomer homes didn’t have olds hanging about. No time for wiping old people’s butts, there are films to see on the telly! My grandparents didn’t know this was coming and didn’t have any idea they’d need to save the money to pay strangers to do what family members had done for every single generation up to the boomers.

I don’t know much about this part of history, so I’ll assume this is true.

So . . . since you’re so against this, you’re going to reverse it by taking great care of your own elderly parents, in your house, attending to their every need, right?

I think most people will wave this off with a “well, since the Boomers destroyed the social contract, now I’m no longer bound by it and this is totally fine, but it was still totally unjustifiable when they did it!”

This is a general worry I have with anti-Boomerism - in many cases, hating the Boomers for doing something is an excuse to do the same thing yourself, because you’re just “trapped in the equilibrium the Boomers created” or whatever. I think the real story is that the Boomers did the thing for the same reason you did.

In this case, that real story is about increasing longevity. It’s fine to care for a 70 year old in your house for a few years until they get felled by the flu, and harder to care for a 95 year old for 30 years until the Alzheimers finally gets them.

Leah Libresco Sargent (Other Feminisms) writes:

I think this Against Against Boomers leaves out a common line of complaint: that boomers benefited from traditions they received and chose not to hand on. I’ve got a bit from Michael Brendan Doughterty’s My Father Left Me Ireland in my review: https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/05/16/your-roots-shall-make-ye-free/

“Dougherty writes, “The adult world that I encountered was plainly terrified of having authority over children and tried to exercise as little of it as practicable. […] The constant message of authority figures was that I should be true to myself. I should do what I loved, and I could love whatever I liked. I was the authority.”

He could write to his father, he could order Gaelic books, but there was no clear way to regain what had been given up by the generations that came before.”

This is also, in miniature, Patrick Deneen’s contention in Why Liberalism Failed: that, gradually, people dismantled the traditions they themselves had benefited from, because they saw them as cruft, not realizing they were load bearing.

Leah gets a pass on this one, because she’s one of the tiny handful of people pumping against entropy and trying to rebuild old traditions.

For everyone else, I make the same accusation as above. The Boomers didn’t raise their children properly because they were evil people who hated the social fabric. I raise my children via a collection of nannies, daycares, and smartphone apps because the economy’s so tough these days that it’s unfair to ask me to do otherwise, plus everyone knows childcare is exploitative uncompensated emotional labor, plus the government should tax the ultra-rich to pay me a childcare allowance, and anyhow it’s the Boomers’ fault for reminding me that I had the option!

uugr writes:

It seems like you’re proposing the blame that’s currently directed at boomers is (in part?) the fault of population collapse. It’s not that the boomers are stealing on the wealth; they just have all the power because they’re so populous.

Could it be that this is a legitimate sort of boomer-hate, though? Not that they didn’t leave enough to their kids, but that they didn’t leave *enough kids* to leave things to? I’m not sure how one would check the age distribution for this; maybe Kids These Days should be blaming Gen X for that instead. But the older generations would take some responsibility for the shape of the age distribution.

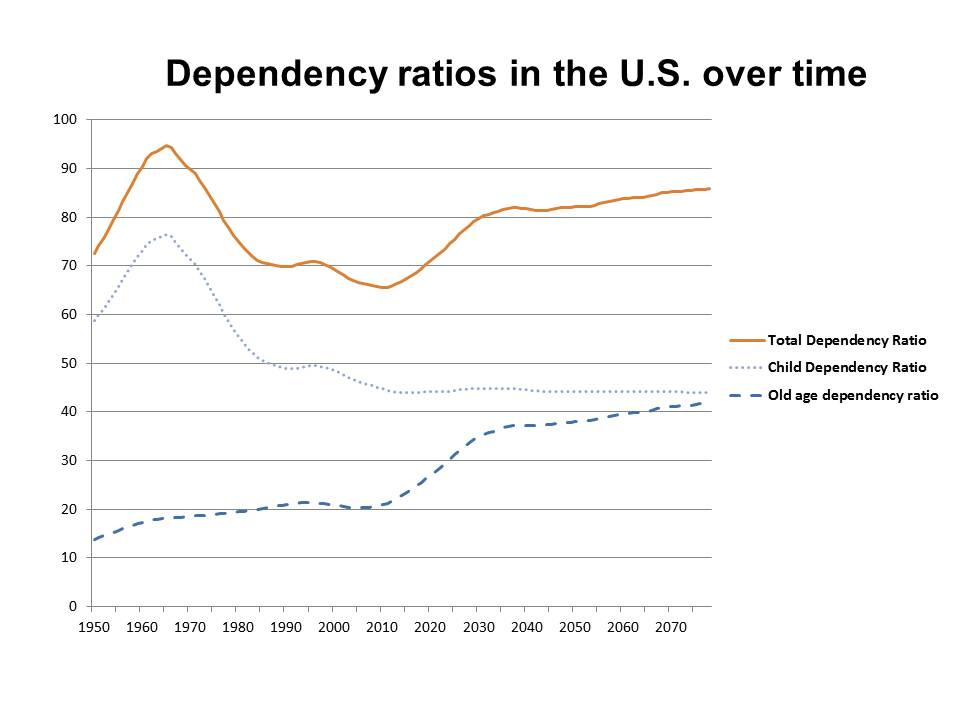

This is an interesting synthesis: most of people’s problems with “the Boomers” are really problems with an inverted demographic pyramid. Since the old outnumber the young, they have “too much” wealth, jobs, etc compared to people’s natural expectation, and previously-solvent benefits programs are falling apart.

Is this right? I actually wasn’t sure where our population pyramid was - I thought maybe the recent wave of immigrants would have righted it - but no, it looks like it’s getting increasingly top-heavy:

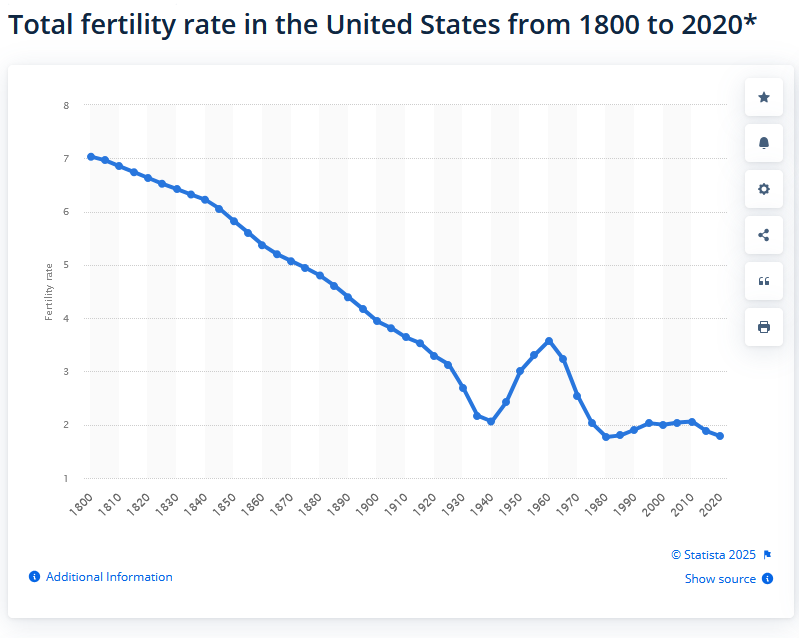

I don’t think it’s especially worth “blaming” the Boomers for this. If you look at the secular trend . . .

…it long predates them, and they’re just reverting to the pre-Baby-Boom mean.

It’s pretty funny that a gigantic boom in robots is about to save us from this right when it starts becoming a noticeable problem.

4: Comments About Social Security Technicalities

…

Matthew writes:

> even when their benefits per capita per year are stable or declining

It looks very different if you look at it by the household level instead of individual

A meaningful share of the increase in total costs comes from composition.

As women shifted from spouse-only benefits to worker or dual entitlement, more households now receive two lifetime worker benefits rather than one worker plus a spousal benefit. Average household payouts rise as a result.

This creates bifurcated outcomes. Households with two lifetime earners receive higher total payments, while single earner and spousal benefit households account for a smaller share of distributions (and directly effected by cuts). Individual averages are skewed by survivorship and changing household structure.

The result is a shift in where Social Security dollars go. A larger share of total payouts now flows to higher lifetime earnings households, which also tend to have lower fertility on average, affecting the system wide distribution of a fixed payroll tax base.

Basically the ratio of working to pay not for your own parents but someone else’s parents who are quite possibly richer than your own has gone up quite a bit.

Tunnelguy writes:

Section III missed that the 2025 tax bill literally has a tax deduction for seniors https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Big_Beautiful_Bill_Act#Tax_credit_for_seniors (often called “No Tax on Social Security”, but that’s not exactly accurate). Agree with the conclusion overall though

Andy G writes:

“Why do so many believe that old people have discovered a vote-themselves-infinite-benefits hack?”

I’m a tail-end Boomer myself, and I mostly agree with your overall take.

But the above quoted concern is actually valid when it comes to the old-age entitlements.

Congress changed SS in the 1970s to have ever-increasing benefits (going up with average wage growth, not merely with CPI) where they don’t have to vote each year on the benefits.

Medicare was never self-funding.

As the number of retirees has grown and there are ever fewer number of workers to pay into the Ponzi-like scheme that is SS, people correctly fear that the Boomers will get all of theirs, but then the Ponzi-scheme will likely end (Medicare is actually in far worse shape than SS (which could still be saved by eliminating that increase by average wage growth provision - would address 80% of the problem).

This is a good point, but it also frames the problem a little too lucidly for its own good.

The problem with the Boomers is that they selfishly refuse to collapse the Social Security Ponzi scheme on themselves, because they selfishly feel like just because they paid into it, they should get benefits.

Why is it bad that the Boomers won’t collapse the Ponzi? Because then we, the Millennials and Zoomers, will soon be in the unfair position of having paid into it, but not receiving benefits!

5: What Are We Even Doing Here?

…

Darwin writes:

Looking at some ‘wealth by generation over time’ graphs, I have an intuition that there’s a stable and repeating pattern in the US of the elderly accumulating all the wealth and power while the young are struggling and disenfranchised. And that this creates a legitimate and perpetual intergenerational conflict where the old people really are hurting the young by keeping wealth away from them and passing policies that benefit themselves and their preferences. Plus probably the gerontocracy genuinely slows down progress and improvement by resisting new ideas and paradigm shifts for as long as physically possible.

(and yes, I’m saying this despite material conditions improving over time in general - this is a separate point about relative positions and interests at a given timepoint)

Assume that pattern is true, you could look at each generation noticing this dynamic with their parents/grandparents generation, blaming that older generation as particularly bad, and failing to notice and address the repeating pattern and the structural factors that cause it, and say they are being foolish and unfair and mistaken.

And you wouldn’t exactly be wrong, but, I still have two basic objections to this take.

The first is that it seems to hold people to a very high standard. At a societal level, I’m glad they even noticed the conflict and tried to take coordinated action to address it at all, a lot of problems never make it that far. And expecting people with no background in history to notice historical trends extending into times they weren’t alive for, especially ones going back before modern digital record-keeping that they can easily Google, is a lot to ask.

The second is that... well, imagine there’s a slave on a southern plantation being whipped. Yes, in a certain sense, the master holding the whip is not unusual from any other master holding any other whip on any other plantation, and the system of slavery implemented across all of those plantations is not unusual from many other systems of slavery that have existed across human history.

In a sense, yes, the slave’s real problem is with the institution of slavery itself, or the facets of human nature and economics that make it a recurring pattern across human societies. That’s the real villain, here.

But I don’t think he’s wrong to also hate, or to blame, the individual person holding the whip.

Even if the societal pattern is the overarching problem here, even if the master in questions wouldn’t even be holding a whip if they were born into a different system with different institutions and different incentives... I still think it’s right to hate and attack that person.

I find this a useful framing too. Don’t hate the player, hate the game - but if the game is bad enough, hating the player is a natural human response.

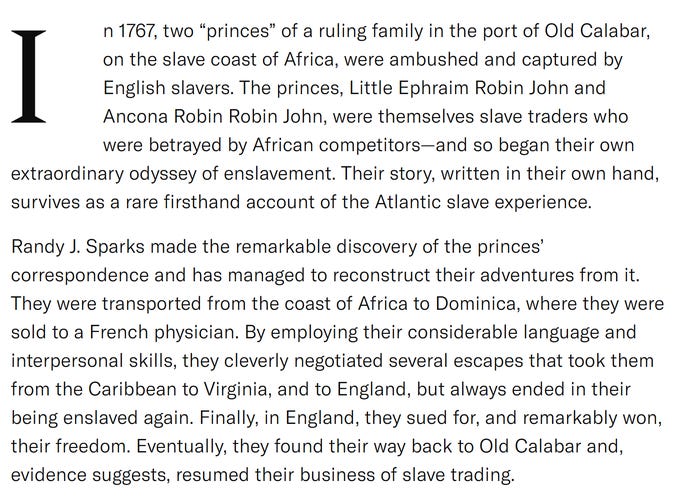

This does, however, remind me of the following story, which I recently encountered on Twitter (h/t @docneto) and can’t stop thinking about:

Does Little Ephraim Robin John have the right to hate the hand that holds the whip? If he doesn’t, where’s the boundary between literally being him, vs. being the sort of person who would have been him if raised in his exact socioeconomic conditions (probably lots of people)?

habu71 writes:

I don’t think you get to hold the boomers blameless for shutting down nuclear simply because today their opinions have shifted and are more pro nuclear than they used to be.

It was their youthful indiscretion that resulted in the NRC being created and soon after turning into the terrible horrible no good destroyer of all things nuclear.

Yeah, this gets into tough questions around blame and the three different things I asked people to disambiguate at the beginning of the post.

It also runs into the same question that darwin asked above: suppose that in 1970, every generation living at the time thought nuclear was bad. And today, every generation living now thinks nuclear is good. On some level, this isn’t the fault of any particular generation - it seems like the information environment in 1970s just wasn’t conductive to figuring this out (although of course you can question who created that information environment). Unless you’re a very special person, if you lived in 1970 then you would have been anti-nuclear too. So can we blame the real 1970ites for their anti-nuclear opinions? I guess in the same sense that we can blame slaveowners, but that’s not an answer.

Richard Hanania writes:

There’s a lot to quibble with in this piece, but on this part I’ll repost here what I recently told Scott via email:

Is anti-old a particularly terrible form of prejudice? Here’s where I disagree the most. How many genocides and mass killings in history have been penetrated based on age? People seem much more willing to commit atrocities in the name of oppressing a rival class, religion, or race. Oppression based on sex has been almost ubiquitous. But being anti-old people goes against the grain of human nature. That’s a feature, not a bug. We all have old relatives, and we’ll all be old. You seem to worry that this will lead to self-loathing and negative stereotypes that we’ll all suffer from in the future. But I’m concerned more about the immediate problems of housing prices, the coming entitlements crisis, and finding an alternative to right- and left-wing forms of populism, which have the wind at their backs. Criticisms based on age never causes as much psychic damage to people as those based on race, sex, and sexual orientation.

The Boomers themselves I think showed how relatively benign prejudice against the old is. in the 1960s and 1970s, they talked about being oppressed by older generations. It never led to mass killings, or systematic discrimination or anything like that. In fact, the old continued to acquire more money and resources and the welfare state has been expanding with more and more money going to them. My hope is that ageism can be strong and compelling enough to motivate some budgetary and housing reforms, while being too weak to lead to the downsides we see in other forms of identity politics.

I think (based on other things, including Hanania’s email) that he is interested in anti-old-ism as a useful political project that can potentially build a coalition to achieve the things he really wants, like economic dynamism. If he could get those things more easily by making people hate the young, he would recommend hating the young.

I can only plead that I’m still Less Utilitarian Than Thou. My post was meant to argue that Boomers don’t deserve hatred. If your objection is that they may not deserve hatred, but that hating them will have good consequences, and so you recommend it anyway - then this seems like the sort of thing that often goes badly, even if you can’t predict exactly how.

Hanania argues that nobody will genocide the old, and I agree. But it brings to mind some of the arguments around the beginning of wokeness, where people justified anti-white rhetoric by saying it was basically harmless - obviously in a 65% white country where white people hold most positions of power, nobody will genocide the whites. This was true as far as it goes, but making anti-whiteness a state ideology for ten years sure did manage to have lots of hard-to-predict bad consequences (and I count the backlash against it as a consequence).

In any case, I’m not using this blog to design a propaganda project or build a coalition. I just like saying things that I think are true.

6: Other Comments

…

Joe and Seth write:

It’s... simplistic, to say this is about hate. It’s a shifting equilibrium, and while the greatest/boomers built most of what we would call the modern world, it is not difficult to recognize that they’re operating on shorter time frames than most of the rest of us have to, and this drives some of their politics as a bloc.

I see this as the same argument against (overwhelmingly the low-skilled segment of) immigration: WEIRD societies tend to be cooperative and trusting and think in longer time frames. This is a fragile equilibrium and is threatened by a demographic shift towards those who are more opportunistic and think in short time frames. Look at trust studies across countries. Yes, there’s significant impact based on the government and support structures in place, but there’s population-level effects too. Age is just a very obvious indicator of the same kinds of prioritization.

I’ll reiterate the point I made in Why I Am Not A Conflict Theorist - although it makes intuitive sense that Boomers, being older, would be more short-termist, these kinds of intuitive stories about how people vote in their self-interest are false.

Federal deficit spending is the clearest possible example of trading off long-term prosperity for short-term gain, but the young are more likely to support it than the old. Climate change is another place where people are being asked to sacrifice now to prevent future disaster, and the generation gap is miniscule.

I don’t blame people for not knowing this, because most polls try really hard to show the opposite - for example, the first thing you’ll find if you look up opinions on deficit spending separated by generation is questions about “should we decrease deficit spending, which will probably involve cutting entitlements to the old?”, and naturally old people are more likely to be against this framing. But you can prove anything by changing poll framing: if you asked “should we decrease deficit spending, which will probably also involve cutting entitlements to the young?”, probably young people would be more against it. When you don’t hold the respondent’s hand and guide them to the answer you want, the young are more pro-deficit-spending.

I think there’s an effect where media wants to tell an exciting story about selfishness and conflict, so they really play up the stories where polls suggest groups are acting in their own selfish interest. But when you try to cut through this, the effect is miniscule, and swamped by whether the group is more Democrat or Republican. Until recently, old people have been more Republican, so they were more likely to want to cut the deficit.

Daniel Kang writes:

I have no thoughts on Boomers in general, but the Schrodinger’s Immigrant / Schrodinger’s Boomer fall flat to me. A steelman of this argument is:

- There are many immigrants. Some of them are on welfare and others of them are taking jobs

- There are many Boomers. Some Boomers pushed too hard to neoliberalism in some aspects of the economy and others focused on over-regulating the environment in other parts of the economy

I also have no particular thoughts on whether or not this argument is correct, but I think it would be better to present actual steelman arguments.

I responded by saying that when you levy an accusation against a group, you’re arguing not just that some members of the group do X, but that the group has a disproportionate tendency toward X. Daniel and other commenters were not satisfied, and you can read the full discussion here.

Ben Smith writes:

Not to be a punisher reader but this article treats the 1946 generation as if they’re representative of the boomers. In reality boomers are 1946-1964. Only the very oldest of them were sent to Vietnam or were responsible for Woodstock etc. Boomers should be weighed and measured by the youth culture of the late sixties to mid 80s (less so). So Woodstock is fairly theirs, but so is the inward individualist turn on the 1970s.

I appreciate this clarification.

Kamateur writes:

This is also a vibes thing. It’s certainly turned malignant, but most of the millennial contempt I see for boomers at least started out as simple frustration over boomers not recognizing that they had lived in a period where it was relatively easy to accumulate wealth in the form of property and pensions and stable jobs. Essentially its a form of envy, and envy is always the worst when the people you envy act like everything they've achieved is the result of a normal process, as opposed to a confluence of timing and opportunity. The stereotypical boomer, under this model, is your parent who tells you they don't understand why you are still living in a crummy little apartment, not realizing that a mortgage where you live costs four times what you pay in rent.

I kind of want to disagree with this by reiterating the graph showing that Millennials are richer than Boomers (at the same age), but I’m not sure that works. My memories of these sorts of conversations are that even when I’m doing well relative to older people, their advice still grates. Like, yes, I eventually got a great job and am very happy, but no, it was not correct to ask why I didn’t have a job yet at time X, or to ask why I hadn’t solved this problem yet by walking into an office in a nice suit, giving someone a firm handshake, and depositing my resume on their desk.

Mackenzie writes:

There is one aspect of the Boomer generation vis-à-vis institutional power that I don’t see touched upon is this essay that I see as another force driving anit-Boomer sentiment. It’s that Boomers as a cohort have remained in leadership roles for an exceptionally long time in Congress, as executives, etc whereas other generations were faster to transition leadership to others.

This Boomers vs Millennials framing is explained very well in this email exchange between Peter Thiel and Mark Zuckerberg, I recommend the whole email exchange but I’ll heavily quote this reply from Thiel.

» “What I would add to Mark’s summary is that, in a healthier society, the handover from the Boomers to the younger generations should have started some time ago (maybe as early as the 1990s for Gen X), and that for a whole variety of reasons, this generational transition has been delayed as the Boomers have maintained an iron grip on many US institutions. When the handover finally happens in the 2020s, it will therefore happen more suddenly and perhaps more dramatically than people expect or than such generational transitions have happened in the past. And that’s why it’s especially important for us to think about these issues and try and get ahead of them.

One example of such an “iron grip” from my colleague Eric Weinstein: Of the 67 top research universities in the US, 62 have Baby Boomer presidents (three are Silent Generation and only two are Generation X). Today, the median age of these 67 university presidents is 65 years-old... And this is very different from the recent past. Only thirty years ago, in 1990, the median age of these same university presidents was a much lower 52-years old; the older generation did not completely refuse to give up power; and therefore much greater generational diversity was to be found in university leadership.”

Given historical trends you would expect to see much more Gen X leaders in Congress, as presidents, or even as business owners than you do today.

So do we want affirmative action for the young? Why is this better than other forms of affirmative action?

It doesn’t seem like a mystery why institutions would hire older leaders: they have more experience. Probably in the past this was kept in check by the tendency of old people to die (or forcibly retire due to poor health) at a young age, plus a shortage of old people since each generation was larger than the last.

People have this sense that Boomers are being evil and selfish by not retiring so that young people can get more of the good jobs. Why is this a more natural way to think of things than white people being evil and selfish by not voluntarily underemploying themselves so black people can get more of the good jobs?

Much of anti-Boomerism seems to be about how Boomers are selfish because they’re taking up resources, and those resources could go to young people instead. But every group is taking up resources that could go to other groups! This only justifies anti-Boomerism if you start with the assumption that old people are less worthy of having good things than young people, and so if you can’t redistribute old people’s resources to young people, then this is prima facie unfair.

I think there are some weak arguments for why it’s better for young people to have resources than old people, but these don’t seem strong enough to justify the level of Boomer hatred, and I’d like to see people make them explicit.

Charles UF writes:

This is weapons grade overthinking, and a byproduct of the constant demands for evidence and sources that are a strong norm in certain discussion circles. For better insight, read the twitter link from the OP again: https://x.com/search?q=%22you%20don%27t%20hate%20boomers%20enough%22&src=typed_query

I didn’t scroll for hours on this link, but I didn’t see any charts or stats like this post focuses on, and only a few references to economics. What I did see was a tremendous amount of Boomer’s own words and behaviors, often directly from the person themselves as a tweet, email, or text. These posts, I think speak for themselves and conform to the personal experiences a lot of people have had with their own boomer parents.

Even if they can be statistically proven to be no different than any subsequent generation from a metrics point of view, that doesn’t mean they aren’t assholes. I apologize for the profanity but it’s the most succinct term I think.

I’m GenX, born in the 70s. My parents were boomers; their parents, my grandparents, were the greatest generation. We in GenX and some of the oldest Millennials had a front row seat for the generational transition from the Greatest to the Boomers. I think a lot of the hatred stems from our experiences during this time, and I honestly think many of the boomers deserve worse.

My greatest grandparents loved their children and went out of their way to help them as adults any way they could: money, childcare, advice, a place to land when you lost your job. I knew that I could go to my grandparents’ house at any time, **which I could walk to**, and I’d be welcomed with love. And fed. They didn’t move away even though they could afford it; their families were too important. They lived for their grandkids. They really were a great generation.

Now, it’s the boomer’s turn to the grandparents. Cool, they had some great role models. How did that turn out? For the most part they not only do they never help their kids as adults, but they also blame them for everything that has turned out less than ideal in their lives. They don’t offer loving or even useful guidance, they are supremely disinterested in their grandchildren beyond new photos every year for their condo in Florida. Did I mention they moved away as fast as they could and absolutely will not return to where they left their kids (who can’t afford to leave) and grandkids, nor are their families welcome to visit them at their home, which is “too nice” for little kids to ever enter. They’re nasty, anti-social parasites. If it is in fact the case that they haven’t hoarded most of our culture’s wealth, it’s not from lack of motivation to do so.

This is not a universal description obviously, but it’s very close to the experience of a large fraction of the children and grandchildren of boomers. It’s not about charts and graphs and economics or even demography.

They’re assholes. And we knew, and deeply loved, their parents. We were there, and we saw it happen.

This hasn’t been my experience; I’m curious whether it’s Charles or I who is the atypical one. I don’t know how you’d even start investigating this though.

Chance Johnson writes:

Any discussion of Boomers will inevitably devolve into a debate about NIMBYism, the Great American Rent Crisis, etc. Indulge me while I bite that bullet through a detour into the Horn of Africa.

Ethiopia was an economic basket case in the early 80s. Thanks to warfare, their economy is again doing poorly. But in between, they had a miraculous recovery. I read that the catalyst for their resurgence was radical land distribution quickly followed by the return of a capitalist government. A government that enforced free markets and relatively strong rule of law, but refused to undo the redistribution of their Marxist forebears.

This combination of redistribution plus free markets was an accident of history, of course. No Marxist ideologue would admit that a one-time redistribution was the only necessary Marxist policy. Nor would a capitalist ideologue initiate even a one-time redistribution, or admit that the benefits of such a program would outweigh its moral hazards.

So recreating the Ethiopian miracle would be a tall order. But dammit, I wish we could try it here. I really believe that if everyone had an affordable place to live where they didn’t have to worry about getting evicted for purely financial reasons, this security would enable them to be more effective in our capitalist system. Didn’t we do something like this more than once in American history, when the Feds issued sweeping amnesties for squatters on public land?

The key concept here is “security of tenure,” or the stability of knowing you will be able keep the roof over your head, come what may. Even if you lose your job with negligible savings, and it takes you a 6-12 months to get back on track. This security is oblique to the question of ownership vs. renting, and it deserves much more consideration.

I realize this is almost totally unrelated to Boomers, but I’m signal-boosting it anyway to make sure Richard Hanania sees it, since it supports my side of an email argument we had a few weeks ago.

specifics writes:

But didn’t the Boomers themselves arguably invent this strain of intergenerational warfare? “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” etc. You could argue that this is just deserts: They created the midcentury cultural conditions in which youth is worshipped, old age and authority are held in contempt, politics are governed by resentment, and money ultimately matters above all else.

I do not see it that way myself. I think every generation is the victim of their progenitors and the perpetrator of crimes upon their descendants, and the Boomers clearly inherited a fallen world themselves.

I’m not sure who invented it. I just think this seems like a good time to stop.

7: Updates / Conclusions

The most important thing I got from these interactions was learning about the proposal to keep property taxes high, but delay them until death/sale of property. This relieves some of my tension around Prop 13 and related issues.

But Darwin’s comment, and a few others along the same lines, also made me worry that I’m trying to exonerate Boomers through some manuever like “Well, their actions were just the inevitable product of the social/cultural/economic stresses they were under”. Even if this is true, it’s probably true of everyone, including slaveowners and Nazis. It doesn’t seem entirely correct either to blame them or to not blame them under these circumstances, but I should probably think more about whether I’m exonerating Boomers harder than I would exonerate other groups with this same excuse.