Defining Defending Democracy: Contra The Election Winner Argument

...

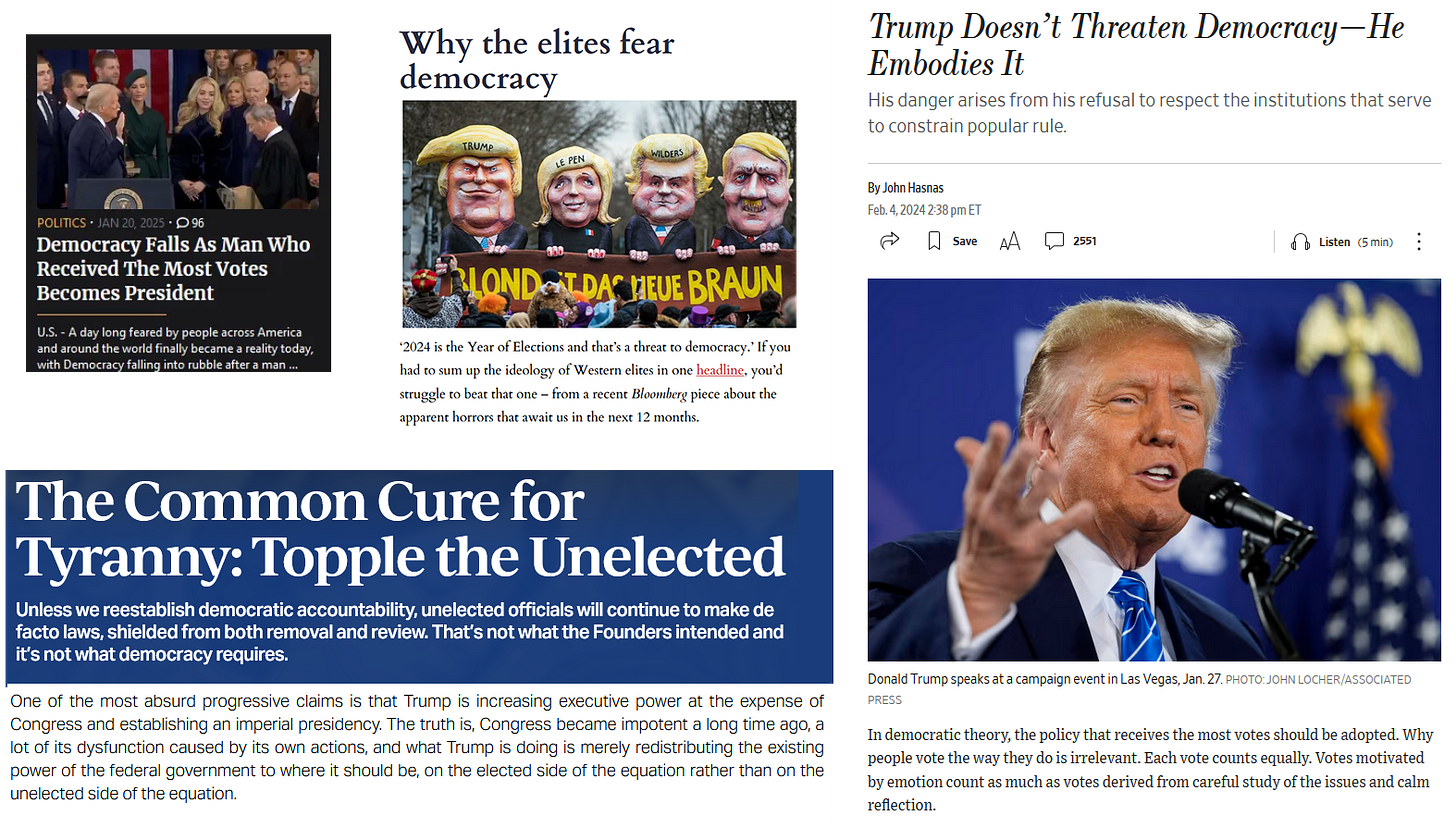

Someone argues that Donald Trump threatens democracy, maybe because he’s asserting authority against the judiciary or the media or the NGOs. Someone else counterargues that it hardly seems undemocratic for someone to favor someone who won an election (the President) over other people who did not (the judiciary, the media). If anything, it seems undemocratic to allow the unelected people to continue to obstruct and harass elected leaders.

The most common response is to say that fine, democracy is about who wins votes, but we also like liberalism, liberalism is under threat, it’s too hard to talk about “liberalism” because in the US it sometimes means being left-wing, and so we use the related concept “democracy” as a stand-in. This is reasonable, and some accused-democracy-destroyers like Viktor Orban even accept it for themselves, calling their brand of government “illiberal democracy”.

But I think there’s an even stronger response that doesn’t require admitting to a bait-and-switch: democracy isn’t just about having an election. It’s about having more than one election.

Imagine a system where the winner of a fair election gets unlimited authority during his term. What forces this person to ever hold another fair election? Why can’t he ban the media from reporting on his missteps? Or confiscate opposition parties’ treasuries? Or order the police to murder any candidate who runs against him? The preparations for the next election, and the election itself, occur while it is still his term; if he can do whatever he wants during his term, there is nothing guaranteeing a fair election besides his personal goodwill.

When we adjust for this - when we consider how to accord a leader enough power to do anything except rig the next election in his favor - we find that this is such a hard problem that it already requires most of the checks, balances, and civil society that we call liberalism.

For example, the simplest way to win an election is to murder opposing candidates. We cannot merely constitutionally ban the leader from murdering people; if the leader controls the judiciary, he can pack it with sympathetic judges who will find him innocent of murder even when he does it in broad daylight (for some reason, no Russian judge has ever convicted Vladmir Putin of any of the assassinations that so many Western sources are sure he committed). So in order to give teeth to even the most basic ban on murdering rival candidates, you need an independent judiciary.

(and although having “unelected bureaucrats” sounds bad, it’s important that these people not be directly elected at exactly the same time as the leader, because if the same electorate that puts the leader in power puts the checks on the leader in power, they’re likely to come from the same party. In the US, we solve this in a variety of ways, especially by staggering appointments - some officials are appointed by the previous leader, or the one before that.)

But an independent judiciary is useless if the leader can ignore it without penalty. And the penalty cannot be purely legal, because legal penalties are levied by a judiciary, ie the organ that such a leader is ignoring. So this penalty must bottom out in extra-legal consequences: either the public relations consequences of the populace realizing that their leader has become a dictator, or - in the worst-case scenario - the military realizing this and taking direct action. But these extra-legal consequences require a well-informed populace (or at least a well-informed military). Now we also need freedom of the press. And a token freedom of the press, only sufficient to print the single line “the leader has defied the judiciary”, won’t be enough. People need context: is there an emergency? Was the judiciary actually trying to overstep? Is this part of a pattern? Is the leader generally a bad enough actor that this should tip people over the edge to vote against him, or to protest him? Many people will be reluctant to protest if the economy is strong and the borders are peaceful; is the economy actually strong, and the border actually peaceful, or is this just state propaganda? Answering these questions requires a flourishing journalistic ecosystem, including investigative reporters.

A well-informed populace is useless without the ability to act on its information. Consider what might happen in a flourishing democracy if a leader tried to fire all the election monitors and replace them with toadies who would stuff the ballot boxes in his favor.

Someone at the election office notices and informs the media (this step goes better if you have whistleblower protections enshrined in law, which may require an independent legislature).

The media reports on it (this step goes better if you have trustworthy independent media)

Some NGO employs constitutional lawyers who are prepared for an issue like this, and they sue to stop the move (this step goes better with a well-funded NGO ecosystem, which itself requires large donors whose money cannot be arbitrarily confiscated)

The NGO wins in court (this step goes better with an independent judiciary). The court very clearly says that this action is illegal, transforming a fuzzy potential misdeed into a bright-line ride-or-die issue. That is, firing election officials sounds bad, but leaders do things that sound bad every day. However, violating a judicial ruling is an immediate obvious constitutional crisis. This is in some sense the entire role of the court system: to collapse a blob of vague seeming-bad-ness into an unmistakable “undo this right away or you will have crossed a bright red line and initiated a constitutional crisis”.

If the leader doesn’t back down, there is an easily recognized constitutional crisis. The people protest the leader’s actions, and his political allies start to desert him. This step goes better if there are civil society groups capable of organizing protests. Optionally and controversially, it might benefit from gun rights groups ensuring that the protesters are armed, channels like Telegram allowing the protesters to communicate with each other, cryptocurrencies preventing the protesters from being easily debanked, and norms against police militarization that ensure the police aren’t already extremely well-trained in crushing protesters.

Hopefully the leader backs down and agrees not to fire the election monitors.

When people accuse a strongman who moves against the judiciary, the media, NGOs, etc, of “threatening democracy”, they mean that he’s taking actions that would weaken some of the links in this chain. These actions might be desirable for other reasons, but they need to justify themselves against the cost of potentially making future elections less fair and free, if the strongman chooses to move in that direction later.

Although in theory this anti-democratic playbook is equally available to left-wing and right-wing leaders (and has been used effectively by some left-wing leaders like Hugo Chavez), to American ears it sounds like a progressive case defending progressive institutions against an inevitably right-wing aggressor. That’s because progressive authoritarianism’s comparative advantage is subverting these institutions from the inside (eg the civil service fails to protest anti-democratic encroachment by progressives because progressives have captured it and it serves their interests) and conservative authoritarianism’s comparative advantage is weakening or attacking these institutions (eg the civil service fails to protest anti-democratic encroachment because the government has limited its power). These strategies are both bad, and conservatives can reasonably claim that their own strategy of moving against institutions is a consequence of progressives taking them over, and that if the institutions were still fair then they would not be trying to sideline them as hard.

But nothing about this situation justifies the argument that democracy is not in danger because the person who got most of the vote is still in charge.