I.

An academic once asked me if I was writing a book. I said no, I was able to communicate just fine by blogging. He looked at me like I was a moron, and explained that writing a book isn’t about communicating ideas. Writing a book is an excuse to have a public relations campaign.

If you write a book, you can hire a publicist. They can pitch you to talk shows as So-And-So, Author Of An Upcoming Book. Or to journalists looking for news: “How about reporting on how this guy just published a book?” They can make your book’s title trend on Twitter. Fancy people will start talking about you at parties. Ted will ask you to give one of his talks. Senators will invite you to testify before Congress. The book itself can be lorem ipsum text for all anybody cares. It is a ritual object used to power a media blitz that burns a paragraph or so of text into the collective consciousness.

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book What We Owe The Future have recently been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times, Vox, NPR, BBC, The Atlantic, Wired, and Boston Review. He’s been interviewed by Sam Harris, Ezra Klein, Tim Ferriss, Dwarkesh Patel, and Tyler Cowen. Tweeted about by Elon Musk, Andrew Yang, and Matt Yglesias. The publicity spike is no mystery: the effective altruist movement is well-funded and well-organized, they decided to burn “long-termism” into the collective consciousness, and they sure succeeded.

But what is “long-termism”? I’m unusually well-placed to answer that, because a few days ago a copy of What We Owe The Future showed up on my doorstep. I was briefly puzzled before remembering that some PR strategies hinge on a book having lots of pre-orders, so effective altruist leadership asked everyone to pre-order the book back in March, so I did. Like the book as a whole, my physical copy was a byproduct of the marketing campaign. Still, I had a perverse urge to check if it really was just lorem ipsum text, one thing led to another, and I ended up reading it. I am pleased to say that it is actual words and sentences and not just filler (aside from pages 15 through 19, which are just a glyph of a human figure copy-pasted nine hundred fifty four times)

So fine. At the risk of joining on an already-overcrowded bandwagon, let’s see what we owe the future.

II.

All utilitarian philosophers have one thing in common: hypothetical scenarios about bodily harm to children.

The effective altruist movement started with Peter Singer’s Drowning Child scenario: suppose while walking to work you see a child drowning in the river. You are a good swimmer and could easily save them. But the muddy water would ruin your expensive suit. Do you have an obligation to jump in and help? If yes, it sounds like you think you have a moral obligation to save a child’s life even if it costs you money. But giving money to charity could save the life of a child in the developing world. So maybe you should donate to charity instead of buying fancy things in the first place.

MacAskill introduces long-termism with the Broken Bottle hypothetical: you are hiking in the forest and you drop a bottle. It breaks into sharp glass shards. You expect a barefoot child to run down the trail and injure herself. Should you pick up the shards? What if it the trail is rarely used, and it would be a whole year before the expected injury? What if it is very rarely used, and it would be a millennium? Most people say that you need to pick up the shards regardless of how long it will be - a kid getting injured is a kid getting injured.

(do your intuitions change if you spot glass shards left by someone else, and have to decide whether to pick them up?)

Levin on the Effective Altruist Forum rephrases this thought experiment to be about our obligations to people who aren’t born yet:

You drop the bottle and don't clean it up. Ten years later, you return to the same spot and remember the glass bottle. The shards are still there, and, to your horror, before your eyes, a child does cut herself on the shards.

You feel a pang of guilt, realizing that your lack of care 10 years ago was morally reprehensible. But then, you remember the totally plausible moral theory that hypothetical future people don't matter, and shout out: "How old are you?"

The child looks up, confused. "I'm eight."

"Whew," you say. Off the hook! While it's a shame that a child was injured, your decision not to clean up 10 years ago turns out not to have had any moral significance.

So it would appear we have moral obligations to people who have not yet been born, and to people in the far future who might be millennia away. This shouldn’t be too shocking a notion. We talk about leaving a better world for our children and grandchildren, and praise people who “plant trees in whose shade they will never sit”. Older people may fight climate change even though its worst effects won’t materialize until after they’re dead. When we build nuclear waste repositories, we try to build ones that won’t crack in ten thousand years and give our distant descendants weird cancers.

But the future (hopefully) has more people than the present. MacAskill frames this as: if humanity stays at the same population, but exists for another 500 million years, the future will contain about 50,000,000,000,000,000 (50 quadrillion) people. For some reason he stops there, but we don’t have to: if humanity colonizes the whole Virgo Supercluster and lasts a billion years, there could be as many as 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (100 nonillion) people.

(All those pages full of person glyphs were a half-assed attempt to put these numbers in perspective - half-assed because MacAskill uses each glyph to represent 10 billion people, and cuts it off after five pages despite admitting it would take 20,000 pages to do accurately. Coward.)

Stalin said that one death was a tragedy but a million was a statistic, but he was joking. We usually accept that a disaster which kills a million people is worse than one that kills a thousand. A disaster that killed a billion people would be utterly awful. But the future is 20,000 pages worth of glyphs representing 10 billion people each. Are we morally entangled with all of those people, just as we would have an obligation to pick up a glass bottle that might injure them?

Imagine you are a wise counselor, and you have the opportunity to spend your life advising one country. Whichever country you advise will become much richer and happier (and for whatever reason, you can’t choose your own homeland). You might think: “If I help Andorra, it will only benefit a few thousand people. If I help Lithuania, it will only benefit a few million people. But if I help India, it will benefit over a billion people. So I will devote my life to helping India.” Then you learn about the future, a country with 50 quadrillion people. Seems like a big deal.

Is this just Pascalian reasoning, where you name a prize so big that it overwhelms any potential discussion of how likely it is that you can really get the prize? MacAskill carefully avoids doing this explicitly, so much so that he (unconvincingly) denies being a utilitarian at all. Is he doing it implicitly? I think he would make an argument something like Gregory Lewis’ Most Small Probabilities Aren’t Pascalian. This isn’t about an 0.000001% chance of affecting 50 quadrillion people. It’s more like a 1% chance of affecting them. It’s not automatically Pascalian reasoning every time you’re dealing with a high-stakes situation!

III.

But how do you get a 1% chance of affecting the far future? MacAskill suggests three potential methods: progress, survival, and trajectory change.

Progress is simple: suppose the current GDP growth rate is 2%/year. At that rate, the world ten thousand years from now will be only 10^86 times richer. But if you increase the growth rate to 3%, then it will be a whole 10^128 times richer! Okay, never mind, this is a stupid argument. There are only 10^67 atoms in our lightcone; even if we converted all of them into consumer goods, we couldn’t become 10^86 times richer.

So MacAskill makes a different argument: it would be very bad if technological growth stagnated, and we could never become richer at all. There are a few reasons we might expect that to happen. Technological growth per person is slowing down, and population growth is declining worldwide. Sometimes growth builds on itself; when there is a lot of growth, people are in a good mood and stakeholders are willing to make sacrifices for the future, trusting that there’s much more where that came from. When growth slows, everyone becomes fiercely protective of what they have, and play zero-sum games with each other in ways not conducive to future growth. So one potential catastrophe is a vicious cycle of stagnation that slows growth for millennia. Since our current tech level is pretty conducive to world destruction (we have nukes and the ability to genetically engineer bioweapons, but nothing that can really defend against nukes or genetically-engineered bioweapons), staying at the current tech level for millennia is buying a lot of lottery tickets for world destruction. So one long-termist cause might be to avoid technological stagnation - as long as you’re sure you’re speeding up the good technologies (like defenses against nukes) and not the bad ones (like super-nukes). Which you never are.

Survival is also simple. MacAskill introduces it with a riddle of Derek Parfit’s. Assuming there are 10 billion people in the world, consider the following outcomes:

A. Nothing bad happens

B. A nuclear war kills 9 billion people

C. A slightly bigger nuclear war kills all 10 billion people, driving humanity extinct

Clearly A is better than B is better than C. But which is bigger: the difference between A and B, or the difference between B and C? You might think A - B - after all, there’s a difference of 9 billion deaths, vs. a difference of only 1 billion deaths between B and C. But Parfit says it’s B - C, because this kills not only the extra 1 billion people, but also the 50 quadrillion people who will one day live in the far future. So preventing human extinction is really important.

But it is hard to drive humans extinct. MacAskill goes over many different scenarios and shows how they will not kill all humans. Global warming could be very bad, but climate models show that even under the worst plausible scenarios, Greenland will still be fine. Nuclear war could be very bad, but nobody wants to nuke New Zealand, and climate patterns mostly protect it from nuclear winter. Superplagues could be bad, but countries will lock down and a few (eg New Zealand) might hold on long enough for everyone else to die out and the immediate threat of contagion to disappear. MacAskill admits he is kind of playing down bioweapons for pragmatic reasons; apparently al-Qaeda started a bioweapons program after reading scaremongering articles in the Western press about how dangerous bioweapons could be.

(what about AI? MacAskill deals with it separately: he thinks in some sense an AI takeover wouldn’t count as extinction, since the AI still exists.)

Suppose that some catastrophe “merely” kills 99% of humans. Could the rest survive and rebuild civilization? MacAskill thinks yes, partly because of the indomitable human spirit:

[Someone might guess that] even today, [Hiroshima] would be a nuclear wasteland…but nothing could be further from the truth. Despite the enormous loss of life and destruction of infrastructure, power was restored to some areas within a day, to 30% of homes within two weeks, and to all homes not destroyed by the blast within four months. There was a limited rail service running the day after the attack, there was a streetcar line running within three days, water pumps were working again within four days, and telecommunications were restored in some areas within a month. The Bank of Japan, just 380 metres from the hypocenter of the blast, reopened within just two days.

…but also for good factual reasons. For example, it would be much easier to reinvent agriculture the second time around, because we would have seeds of our current highly-optimized crops, plus even if knowledgeable farmers didn’t survive we would at least know agriculture was possible.

His biggest concern here is reindustrialization. The first Industrial Revolution relied on coal. But we have already exhausted most easy-to-mine surface coal deposits. Could we industrialize again without this resource? As any Minecraft player knows, charcoal is a passable substitute for coal (apparently Brazil’s steel industry runs on it!) But:

The problem is that it’s not clear whether we would be able to redevelop the efficient steam turbines and internal combustion engines needed to harness the energy from charcoal. In the Industrial Revolution, steam turbines were first used to pump out coal mines to extract more coal. As Lewis Dartnell says, “Steam engines were themselves employed at machine shops to construct yet more steam engines. It was only once steam engines were being built and operated that subsequent engineers were able to devise ways to increase their efficiency and shrink fuel demands…in other words, there was a positive feedback loop at the very core of the industrial revolution: the production of coal, iron, and steam engines were all mutually supportive.

So rebuilding industrial civilization out of charcoal is iffy. The good news is that there are a few big remaining near-surface coal deposits. MacAskill suggests that although the main reason to stop mining coal is because of climate change, a second reason to stop mining coal is to leave those few remaining deposits alone in case our distant descendants need them. Also, we should tell them to get it right next time: there might be enough coal left to industrialize one more time, but that’s it.

Trajectory change is the most complicated way of affecting the future. Can we change society for the better today, in some way that gets locked in such that it’s still better a thousand or a million years from now?

This might not be impossible. For example, Mohammed asked Muslims not to eat pork, and they still follow this command thousands of years later. The US Constitution made certain design decisions that still affect America today. Confucianism won the philosophical squabbles in China around the birth of Christ, and its ethos still influences modern China.

MacAskill frames this in terms of value malleability and value lock-in. There is a time of great malleability: maybe during the Constitutional Convention, if some delegate had given a slightly more elegant speech, they might have ditched the Senate or doubled the length of a presidential term or something. But after the Constitution was signed - and after it developed centuries of respect, and after tense battle lines got drawn up over every aspect of it - it became much harder to change the Constitution, to the point where almost nobody seriously expects this to work today. If another Chinese philosopher had fought a little harder in 100 BC, maybe his school would have beaten Confucius’ and the next 2000 years of Chinese history would have looked totally different.

We might be living at a time of unusual value malleability. For one thing, this graph:

…suggests this is not exactly the most normal time. Growth can’t go on like this forever; eventually we run into the not-enough-atoms-to-convert into-consumer-goods problem. So we are in an unusual few centuries of supergrowth between two many-millennia-long periods of stagnation. Maybe the norms we establish now will shape the character of the stagnant period?

But also, we seem about to invent AI. It is hard to imagine the future not depending on AI in some way. If only dictators have AI, maybe they can use it to create perfect surveillance states that will never be overthrown. If everyone benefits from AI, maybe it will make dictatorships impossible. Or maybe the AIs themselves will rule us, and their benevolence level will depend on how well we design them.

Objection: Mohammed, Washington, and Confucius shaped the future. But none of them could really see how their influence would ripple through time, and they might not be very happy with the civilizations they created. Do we have any examples of people who aimed for a certain positive change to the future, achieved it, and locked it in so hard that we expect it to continue even unto the ends of the galaxy?

MacAskill thinks yes. His example is the abolition of slavery. The Greeks and Romans, for all their moral philosophy, never really considered this. Nor was there much abolitionist thinking in the New World before 1700. As far as anyone can tell, the first abolitionist was Benjamin Lay (1682 - 1759), a hunchbacked Quaker dwarf who lived in a cave. He convinced some of his fellow Quakers, the Quakers convinced some other Americans and British, and the British convinced the world.

There’s a heated scholarly debate about whether the end of slavery was an inevitable consequence of the shift from feudalist to industrial-capitalist modes of production, or whether it was a contingent result of the efforts of abolitionist campaigners. MacAskill tentatively takes the contingent side. At the very least, the British campaigners weren’t just sitting back and letting History do its work:

At the time of abolition slavery was enormously profitable for the British. In the years leading up to abolition, British colonies produced more sugar than the rest of the world combined, and Britain consumed the most sugar of any country. When slavery was abolished, the shlef price of sugar increased by about 50 percent, costing the British public £21 million over seven years - about 5% of British expenditure at the time. Indeed, the slave trade was booming rather than declining: even though Britain had abolished its slave trade between 1807, more Africans were taken in the transatlantic slave trade between 1821 and 1830 than any other decade except the 1780s. The British government paid off British slave owners in order to pass the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which gradually freed the enslaved across most of the British Empire. This cost the British government £20 million, amounting to 40% of the Treasury’s annual expenditure at the time. To finance the payments, the British government took out a £15 million loan, which was not fully paid back until 2015.

The economic interpretation of abolition also struggles to explain the activist approach that Britain took to the slave trade after 1807. Britain made treaties, and sometimes bribes, to pressure other European powers to end their involvement in the trade and used the Royal Navy’s West African Squadron to enforce those treaties. Britain had some economic incentive here to prevent their rivals from selling slave-produced goods at lower prices than they could. But the scale of their activism doesn’t seem worth it: from 1807 to 1867, enforcing abolition cost Britain almost 2% of its annual national income, several times what Britain spends today on foreign aid; political scientists Robert Pape and Chaim Kaufmann described this campaign as “the most expensive international moral effort in modern history”.

Race-based slavery ended in the US in 1865 and in Brazil in 1888. Saudi Arabia ended its own form of slavery in 1962. Since then there has been some involuntary labor in prisons and gulags, but nothing like the system of forced labor that covered most of the world in the early 1800s. And although we may compare some modern institutions to slavery, it seems almost inconceivable that slavery as open and widespread as the 19th century norm could recur without a total change of everything in society.

So do we credit abolitionists with locking in better values for all time? MacAskill wants to do this, but I’m not sure. I think he amply proved that abolitionists made slavery end sooner than it would have otherwise. But would we still have widespread race-based slavery in 1950 without the Quakers and the British abolitionists? Would we still have it today? Or were they the leading edge of a social movement that would have spawned other activists to take up the cause if they had faltered? MacAskill admits that scholars continue to disagree on this.

But he still thinks that one of the most important things is to lock in changes like this now, before it gets harder. MacAskill doesn’t mention it, but slavery came to the US very gradually, and if a few 1600s court cases had gone the other way it might not have gotten started at all, or might have been much less severe than it was. It would have been much easier to swing those few court cases than the actual method of waiting until half the country had an economy and lifestyle centered around slavery, then fighting a civil war to make it change its economy and lifestyle. What is at the “swing a few court cases” stage today?

MacAskill doesn’t talk about this much besides gesturing about something something AI. Instead, he focuses on ideas he calls “moral entrepreneurship” and “moral exploration”; can we do what Benjamin Lay did in the 1700s and discover moral truths we were missing before of the same scale as “slavery is wrong”? And can we have different countries with different systems (he explicitly mentions charter cities) to explore fairer systems of government? Then maybe once we discover good things we can promote them before AI or whatever locks everything in.

I found this a disappointing conclusion to this section, so I’ll mention one opportunity I heard about recently: let’s be against octopus factory farming. Octopi seem unusually smart and thoughtful for animals, some people have just barely started factory farming them in horrible painful ways, and probably there aren’t enough entrenched interests here to resist an effort to stop this. This probably won’t be a legendary campaign that bards will sing about for all time the way abolitionism was, but I don’t know how you find one of those. Maybe find a hunchbacked Quaker dwarf who lives in a cave, and ask what he thinks.

IV.

There’s a moral-philosophy-adjacent thought experiment called the Counterfactual Mugging. It doesn’t feature in What We Owe The Future. But I think about it a lot, because every interaction with moral philosophers feels like a counterfactual mugging.

You’re walking along, minding your own business, when the philosopher jumps out from the bushes. “Give me your wallet!” You notice he doesn’t have a gun, so you refuse. “Do you think drowning kittens is worse than petting them?” the philosopher asks. You guardedly agree this is true. “I can prove that if you accept the two premises that you shouldn’t give me your wallet right now and that drowning kittens is worse than petting them, then you are morally obligated to allocate all value in the world to geese.” The philosopher walks you through the proof. It seems solid. You can either give the philosopher your wallet, drown kittens, allocate all value in the world to geese, or admit that logic is fake and Bertrand Russell was a witch.

This is how I feel about the section on potential people.

Suppose you were considering giving birth to a child who you knew would be tortured for their entire life, and spend every moment wishing they were never born. Maybe you know you have a gene for a horrible medical condition which will make them nonfunctional and in constant pain. Seems bad, right? Having this kid is actively worse than not having them.

Now suppose you were considering giving birth to a child who you knew would have an amazing wonderful life. I don’t know how you know this, maybe an oracle told you. They will mysteriously never consume any resources, make the planet more crowded, or make anyone else’s life worse in any way. They’ll just spend every second being really happy they exist. Is having this kid actively morally good? Better than not having them at all? By some kind of symmetry with the constant pain kid, it seems like it should be.

Or you could think of this on a population level. Which is better, a world with ten million happy people, or one with ten billion equally happy people? Suppose the world has infinite resources, we don’t have to worry about overcrowding, each new person is happy to exist but doesn’t make anyone else worse off. Wanting the ten billion happy people seems like kind of the same intuition as wanting to give birth to the happy child; all else being equal, it’s better to create new happy people than not to do so.

MacAskill makes a more formal argument here. Suppose we agree that having the child with the gene for the horrible medical condition that leaves them nonfunctional and in constant pain is morally wrong. Now we gradually dial down the badness of the medical condition until we reach a point where it’s exactly-morally-neutral to have the child (if you believe it’s always wrong to have a child who would have a medical condition, consider that I carry a gene for male-pattern baldness, my child will probably inherit it, but I don’t think it’s wrong for me to have children). Having the child who will have this minorly-bad medical condition is exactly morally neutral.

Is it better to have a healthy child than a child with a medical condition? Seems like yes! For example, if you have a vitamin deficiency during pregnancy, and your doctor tells you to correct it so your child doesn’t develop a medical, most people would correct the deficiency. Or if a woman abused recreational drugs during her pregnancy and this caused her child to have a medical condition, we would agree that is morally bad. So having a healthy child is better than having a child with a medical condition. But we already agreed that having the child with the mild medical condition is morally neutral. So it seems that having the healthy child must be morally good, better than not having a child at all.

Now the mugging: if you agree that creating new happy people is better than not doing that, you can prove that a world full of lots of very poor, almost-suicidal people is better than one full of a smaller number of much richer, happier people.

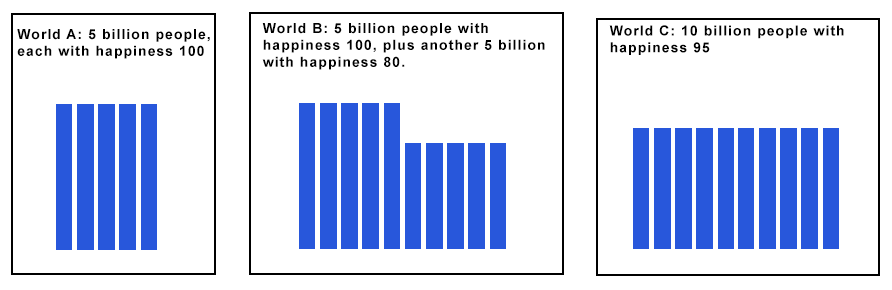

The proof: start with World A, full of 5 billion very happy people. Let’s call them happiness level 100, the happiest it is possible to be, where 0 is neutral happiness (you genuinely don’t care if you live or die), and -100 is maximum unhappiness (you strongly wish you were never born).

Suppose you have the option to either keep World A or switch to World B, which has the same 5 billion happy people, plus another 5 billion people at happiness 80 (so slightly less happy, but still doing very well). These people aren’t taking any resources from the first group. Maybe they live on an entirely different planet or something. You can create them with no downside to any of the people who already exist. Do you keep World A or switch to World B? You switch to B, right? 5 billion extra quite happy people with no downside.

Okay, now you can keep World B or switch to World C. World C has 10 billion people, all at happiness 95. So on average it’s better then World B (which has 10 billion people, average happiness 90). Sure, some people will be worse off. But you’re not any of these people. You’re just some distant god, choosing which worlds to exist. Also, none of these people deserve or earned their happiness in any way. They just blinked into existence with a certain happiness level. So it only seems fair to redistribute the happiness evenly. Plus doing that makes everyone happier on average. So sure, switch from World B to World C.

So now we’ve gone from World A (5 billion people with happiness 100) to World C (10 billion people with happiness 95). You will not be surprised to hear we can repeat the process to go to 20 billion people with happiness 90, 40 billion with 85, and so on, all the way until we reach (let’s say) a trillion people with happiness 0.01. Remember, on our scale, 0 was completely neutral, neither enjoying nor hating life, not caring whether they live or die. So we have gone from a world of 10 billion extremely happy people to a trillion near-suicidal people, and every step seems logically valid and morally correct.

This argument, popularly called the Repugnant Conclusion, seems to involve a sleight-of-hand: the philosopher convinces you to add some extra people, pointing out that it won’t make the existing people any worse. Then once the people exist, he says “Ha! Now that these people exist, you’re morally obligated to redistribute utility to help them.” But just because you know this is going to happen doesn’t make the argument fail.

(in case you think this is irrelevant to the real world, I sometimes think about this during debates about immigration. Economists make a strong argument that if you let more people into the country, it will make them better off at no cost to you. But once the people are in the country, you have to change the national culture away from your culture/preferences towards their culture/preferences, or else you are an evil racist.)

Can we solve this by saying that it’s not morally good to create new happy people unless their lives are above a certain quality threshold? No. In another mugging, MacAskill proves that if you accept this, then you must accept that it is sometimes better to create suffering people (ie people being tortured whose lives are actively worse than not existing at all) than happy people. I’ll let you read the book for the proof.

Can we solve this by saying you can only create new people if they’re at least as happy as existing people - ie if they raise the average? No. This time the proof is easy: suppose there are five billion people in hell, leading an existence of constant excruciating suffering (happiness -100). Is it morally good to add five billion more people with slightly less constant excruciating suffering (happiness -90) to hell? No, this is obviously bad, even though it raises the average from -100 to -95. So raising the average isn’t quite what we’re after either.

MacAskill concludes that there’s no solution besides agreeing to create as many people as possible even though they will all have happiness 0.001. He points out that happiness 0.001 might not be that bad. People seem to avoid suicide out of stubbornness or moral objections, so “the lowest threshold at which living is still slightly better than dying” doesn’t necessarily mean the level of depression we associate with most real-world suicides. It could still be a sort of okay life. Derek Parfit describes it as “listening to Muzak and eating potatoes”. He writes:

The Repugnant Conclusion is certainly unintuitive. Does that mean that we should automatically reject the total view? I don’t think so. Indeed, in what was an unusual move in philosophy, a public statement was recently published, cosigned by twenty-nine philosophers, stating that the fact that a theory of population ethics entails the Repugnant Conclusion shouldn’t be a decisive reason to reject that theory. I was one of the cosignatories.

I hate to disagree with twenty-nine philosophers, but I have never found any of this convincing. Just don’t create new people! I agree it’s slightly awkward to have to say creating new happy people isn’t morally praiseworthy, but it’s only a minor deviation from my intuitions, and accepting any of these muggings is much worse.

If I had to play the philosophy game, I would assert that it’s always bad to create new people whose lives are below zero, and neutral to slightly bad to create new people whose lives are positive but below average. This sort of implies that very poor people shouldn’t have kids, but I’m happy to shrug this off by saying it’s a very minor sin and the joy that the child brings the parents more than compensates for the harm against abstract utility. This series of commitments feels basically right to me and I think it prevents muggings.

But I’m not sure I want to play the philosophy game. Maybe MacAskill can come up with some clever proof that the commitments I list above imply I have to have my eyes pecked out by angry seagulls or something. If that’s true, I will just not do that, and switch to some other set of axioms. If I can’t find any system of axioms that doesn’t do something terrible when extended to infinity, I will just refuse to extend things to infinity. I can always just keep World A with its 5 billion extremely happy people! I like that one! When the friendly AI asks me if I want to switch from World A to something superficially better, I can ask it “tell me the truth, is this eventually going to result in my eyes being pecked out by seagulls?” and if it answers “yes, I have a series of twenty-eight switches, and each one is obviously better than the one before, and the twenty-eighth is this world except your eyes are getting pecked out by seagulls”, then I will just avoid the first switch. I realize that will intuitively feel like leaving some utility on the table - the first step in the chain just looks so much obviously better than the starting point - but I’m willing to make that sacrifice.

I realize this is “anti-intellectual” and “defeating the entire point of philosophy”. If you want to complain, you can find me in World A, along with my 4,999,999,999 blissfully happy friends.

V.

These kinds of population ethics problems are just one chapter of What We Owe The Future (if you want the book-length treatment, read Reasons and Persons), and don’t really affect the conclusion, which is…

What is the conclusion? MacAskill wants you to be a long-termist, ie to direct your moral energy to helping the long-term future. He doesn’t say outright that the future deserves your energy more than the present, but taken to its logical conclusion the book suggests this possibility. If you agree, what should you do?

Luckily, the last chapter of WWOTF is called “What To Do?” It admits that we can’t be sure how best to affect the future, and one of its suggestions is trying to learn more. Aside from that, he suggests preparing against existential catastrophes, fighting climate change and fossil fuel depletion (remember, we need that coal in the ground in case we need to rebuild civilization), figuring out what’s up with AI safety, and building robust international institutions that avoid war and enable good governance.

How can we do this? MacAskill is nothing if not practical, so the middle section of the “What To Do” chapter is called “How To Act”:

[Along with charitable] donations, three other personal decisions seem particularly high impact to me: political activism, spreading good ideas, and having children…But by far the most important decision you will make in terms of your lifetime impact is your choice of career.

You can read more about MacAskill’s justifications for each of those claims in the book. What careers does he suggest? Complicated question, but the best place to start looking would be the altruistic career counseling organization he co-founded, 80,000 Hours.

What should we think of all this?

MacAskill is quick to say that he is not advocating that we sacrifice present needs in favor of future ones:

This is good PR - certainly lots of people have tried to attack the book on the grounds that worrying about the future is insensitive when there’s so much suffering in the present, and this gracefully sidesteps those concerns.

Part of me would have selfishly preferred that MacAskill attack these criticisms head-on. If you really believe future people matter, then caring about them at the expense of present people isn’t insensitive. Imagine someone responding to abolitionist literature with “It’s insensitive to worry about black people when there’s so much suffering within the white community.” This argument only makes sense if you accept that white people matter more - but the whole point of abolitionist arguments is that maybe that isn’t true. “It’s insensitive to worry about future people when there’s suffering in the present” only makes sense if you accept that present people get overwhelming priority over future ones, the point MacAskill just wrote a book arguing against. So these aren’t really criticisms of the book so much as total refusals to engage with it. MacAskill could have said so and repeated his arguments more forcefully instead of being so agreeable.

But this is a selfish preference coming from the part of me that wants to see philosophers have interesting fights. Most of me agrees with MacAskill’s boring good-PR point: long-termism rarely gives different answers from near-termism. In fact, I wrote a post about this on the EA Forum recently, called Long-Termism Vs. Existential Risk:

AI alignment is a central example of a supposedly long-termist cause.

But Ajeya Cotra's Biological Anchors report estimates a 10% chance of transformative AI by 2031, and a 50% chance by 2052. Others (eg Eliezer Yudkowsky) think it might happen even sooner.

Let me rephrase this in a deliberately inflammatory way: if you're under ~50, unaligned AI might kill you and everyone you know. Not your great-great-(...)-great-grandchildren in the year 30,000 AD. Not even your children. You and everyone you know. As a pitch to get people to care about something, this is a pretty strong one.

But right now, a lot of EA discussion about this goes through an argument that starts with "did you know you might want to assign your descendants in the year 30,000 AD exactly equal moral value to yourself? Did you know that maybe you should care about their problems exactly as much as you care about global warming and other problems happening today?"

Regardless of whether these statements are true, or whether you could eventually convince someone of them, they're not the most efficient way to make people concerned about something which will also, in the short term, kill them and everyone they know.

The same argument applies to other long-termist priorities, like biosecurity and nuclear weapons. Well-known ideas like "the hinge of history", "the most important century" and "the precipice" all point to the idea that existential risk is concentrated in the relatively near future - probably before 2100.

The average biosecurity project being funded by Long-Term Future Fund or FTX Future Fund is aimed at preventing pandemics in the next 10 or 30 years. The average nuclear containment project is aimed at preventing nuclear wars in the next 10 to 30 years. One reason all of these projects are good is that they will prevent humanity from being wiped out, leading to a flourishing long-term future. But another reason they're good is that if there's a pandemic or nuclear war 10 or 30 years from now, it might kill you and everyone you know.

Eli Lifland replies that sometimes long-termism and near-termism make different predictions; you need long-termism to robustly prioritize x-risk related charities. I am not sure I agree; his near-termist analysis still finds that AI risk is most cost-effective; the only thing even close is animal welfare, which many people reject based on not caring about animals. I think marginal thinking and moral parliament concerns can get you most of the way to an ideal balance of charitable giving without long-termism (see here for more), and that common-sense principles like “it would be extra bad if humanity went extinct” can get you the rest of the way.

MacAskill must take Lifland’s side here. Even though long-termism and near-termism are often allied, he must think that there are some important questions where they disagree, questions simple enough that the average person might encounter them in their ordinary life. Otherwise he wouldn’t have written a book promoting long-termism, or launched a public relations blitz to burn long-termism into the collective consciousness. But I’m not sure what those questions are, and I don’t feel like this book really explained them to me.

Do I have positive wishes for the long-term future anyway? That depends. Is it an honest question? Then yes, I hope we have a long and glorious future, free from suffering and full of happiness. Or is it some kind of trick where five steps later you will prove that I should let seagulls peck out my eyes? Then no, I’ll stick to doing things because I don’t want x-risks to kill me and everyone I know, sorry.

Share this post