Last month I discussed the platforms of twenty-six candidates for California governor. One candidate, author and activist Michael Shellenberger, objected to my characterization of him, so I read his book San Fransicko to learn more and decide whether I owed him an apology.

San Fransicko is subtitled “Why Progressives Ruin Cities”. It builds off the kind of stories familiar to most Bay Area residents:

In the spring of 2021 two colleagues and I went to San Francisco. We first went to check in on the open-air drug scenes in the Tenderloin and United Nations Plaza. It was the usual scenes of people sitting against buildings and injecting drug needles into their necks and feet. There was garbage, old food, and feces everywhere. After a couple of hours, we decided to go out to eat in the Mission. Work was over. We were all looking forward to a relaxing dinner. We were eating ice cream and walking along Valencia Street when a psychotic man, perhaps about thirty years old, began following us and screaming obscenities. When we turned around to look at him, he screamed at us, “What are you looking for, huh! WHAT. ARE. YOU. LOOKING. FOR!” and started walking faster toward us. We walked faster until the man found other people to verbally assault.

Things haven’t always been like this. San Francisco used to be one of the safest and most beautiful cities in the world. Shellenberger opens with the story of a 1970s SF candidate who campaigned on a message of public cleanliness, promising stronger punishments for owners who failed to pick up after their dogs. The message was a hit, so much so that the increased community and social pressure was enough to reverse the dog-poop-in-parks problem with minimal police enforcement.

(that candidate’s name? Harvey Milk)

But jump forward forty years, and:

In 2018, San Francisco’s mayor, London Breed, held a walking tour with television cameras and newspaper reporters in tow. “I will say that there’s more feces on the sidewalks than I’ve ever seen,” said Breed. “Growing up here, that was something that wasn’t the norm.”

“Than you’ve ever seen?” asked the reporter.

“Than I’ve ever seen, for sure,” she said. “And we’re not just talking about from dogs. We’re talking about from humans.”

Complaints about human waste on San Francisco’s sidewalks and streets were rising. Calls about human feces increased from 10,692 to 20,933 between 2014 and 2018. In 2019, the city spent nearly $100 million on street cleaning—four times more than Chicago, which has 3.5 times as many people and an area that is 4.5 times larger.

Between 2015 and 2018, San Francisco replaced more than three hundred lampposts corroded by urine after one had collapsed and crushed a car.

This is a good introduction to San Fransicko. It adequately telegraphs what you’ll be getting in the rest of the book: scenes of devastating human misery and urban decay, little-known tidbits from California history, and very precise statistics.

But that makes it hard to review. It makes enough different claims to leave the reader feeling kind of overwhelmed. If the claims are true, then the book is great and important. If they’re false, it’s bad and damaging. I felt that the fairest way to review this book was to meet it on its own terms with deep dives into ten of its key claims.

Claim 1: Homelessness Isn’t Just About Housing

Nothing is ever just about one thing. But San Fransicko starts by quoting some experts who say homelessness is mostly a matter of poverty and housing costs, then expresses skepticism in that narrative, instead preferring to focus more on drugs and mental illness.

Alyssa Vance investigates whether housing costs predict homelessness at the level of US states, and finds that they do, r^2 = 0.69. The outlier below is DC; removing it brings the correlation to 0.73.

I was suspicious of using a state-based analysis to talk about cities, so I repeated her work with the 50 biggest US cities, using two different sets of price data - one from Kiplinger, one from Zillow. I found the Zillow numbers a little more plausible; here they are:

This was slightly lower, r^2 = 0.42, but still pretty good! I also don’t think my city homelessness data were perfect (people report homelessness data not by city but by “continuum of care area”, and it’s complicated to figure out what the overall population of each area is), so it wouldn’t surprise me if that’s responsible for most of the decay from Alyssa’s analysis to mine.

Here you can see that San Francisco has a pretty high homelessness rate, but no worse than some other big cities like DC, Boston, and New York (Shellenberger, to his credit, mentions this in the book). So how come everyone talks about SF all the time? Alyssa gives two main reasons.

First, SF homeless tend to concentrate in a few areas downtown; this is also where a lot of the tourists and businesspeople are, so the average tourist or businessperson in San Francisco sees a lot more homeless people than they would if they were evenly distributed throughout the city.

And second, SF homeless are less likely to be sheltered than homeless people elsewhere; Shellenberger notes that “over 99% of New York’s homeless have access to shelter. In San Francisco, just 42% do” (see here for other cities).

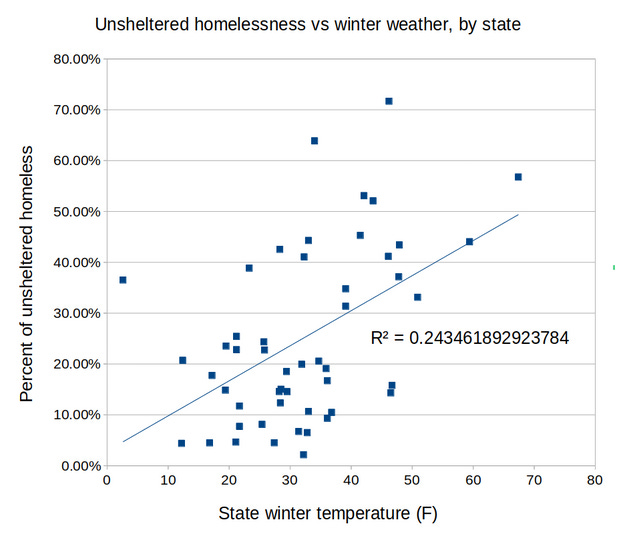

We’ll talk more in Part 4 about why this might be, but one common theory is climate: San Francisco has year-round above-freezing temperatures, so there’s less urgency to shelter everyone. Alyssa shows that the relationship between temperature and percent unsheltered is strong:

So one possible conclusion is that SF has around the amount of homelessness you would predict from its very high housing prices, and around the percent unsheltered you would predict from its balmy winter weather, and there’s nothing further to be explained.

Shellenberger does not like this conclusion.

San Francisco’s mild climate alone cannot explain why it has more homeless people than other cities. Miami, Phoenix, and Houston have year-round warm weather and far fewer homeless than San Francisco per capita. Per capita homelessness in San Francisco, Greater Miami, Greater Phoenix, and Greater Houston in 2020 was 9.3, 1.3, 1.6, and 0.8 per 1,000 residents, respectively. And Greater Miami, Greater Phoenix, and Greater Houston saw their per capita homeless population decline from 2005 to 2020 by 39, 17, and 74 percent while San Francisco saw its rise 30 percent.

Nor can housing prices explain the discrepancy. Palo Alto and Beverly Hills have mild climates and expensive housing but don’t have San Francisco’s homeless problem. As for the Zillow study that was reported to find a correlation between rising rents and homelessness, a deeper look at the research reveals a more nuanced finding. Homelessness and affordability are correlated only in the context of certain “local policy efforts [and] social attitudes,” concluded researchers.

This feels like kind of a shell game. San Francisco’s mild climate alone can’t explain why it has more homeless people per capita than Miami or Houston. But as the graph above shows, housing prices do explain about 75% of the difference between SF and those two cities. But because the book talks about the Miami-SF discrepancy in the paragraph about climate instead of the paragraph about prices, it makes it sound like a mystery that neither prices nor climate can explain.

The Zillow article mentioned is Homelessness Rises Faster Where Rents Exceed A Third Of Incomes, which is based on this study. Shellenberger’s summary is not really the researchers’ conclusion. The article does mention “local attitudes” and “social policy” once, but only to explain that the paper includes a term representing “latent factors” that they’re not going to bother distinguishing from each other in their model, and some of those terms could be local policy or social attitudes. Later they mention there are some outliers in their model (eg Houston), and it would be reasonable to assume that the latent factors help explain the outliers, but they don’t give us any reason to think that this is more interesting than the fact that every model ever will have outliers.

But also, this is one study by Zillow. Alyssa and I both tried the same analysis, and found the same thing, with a correlation that’s unusually high for this kind of work. Sure, there are outliers, but San Francisco isn’t one of them. San Francisco is only a couple of percent off where the regression line would predict.

That leaves the point about Palo Alto and Beverly Hills. They “have mild climates and expensive housing but don’t have San Francisco’s homeless problem”.

At first I felt like this was cheating - yeah, rich suburbs don’t have lots of homelessness, come on. But “rich” and “high property values” are pretty close to synonyms. If you’re going to say that high property values cause homelessness, isn’t it in fact pretty surprising that rich suburbs don’t have it?

In fact, if you’re a homeless person, why wouldn’t you want to live in a suburb? Quieter (so probably easier to sleep at night) more places out of sight to pitch tents, less crime (important if you’re living on the street!), and potentially lower cost of living in terms of food and goods.

I tried looking into this issue and found explanations like:

Usually it’s poor people who become homeless. Cities have more poor people than suburbs, because they have more rental units, small apartments, public transportation, and blue-collar jobs. Suburbs, by natural consequence of their layout, enforce a certain wealth minimum before people can live there, and people above that wealth minimum rarely lose everything and become homeless. It’s strange that poor people tend to live in cities (ie places with very high land values), and you have to wonder whether there are ways that could be different, but it does seem true.

There are some homeless people in suburbs, but they’re less visible because suburbanites usually have cars and ample parking opportunities, so they mostly shelter in their cars out of sight instead of tents on the street.

Suburban police departments might be less tolerant of homeless people, either harassing them until they leave or outright telling them to go to cities. Why would suburban departments be less tolerant than urban departments (especially when urban departments, eg the LAPD, are better known for their ruthlessness)? It might just be an entrenched norms thing; suburbs can get rid of their homeless populations, so they do. Or it might be politics; suburbs might be more conservative than cities.

Cities have better homeless services, and the densest parts of cities have the most homeless services of all, because nobody expects the homeless to be able to commute, so to a first approximation you would only build shelters in places where you expect enough homeless people within walking distance to fill one.

Cities have more of a homeless “community”, in the sense that homeless people can band together for security, friendship, and exchange of goods and services (eg drugs).

Whatever the factors involved, they have to explain not just why there are so few homeless people in Palo Alto, but also why there are so few homeless people in the nicer, less dense parts of San Francisco - as Alyssa points out, about half of the homeless in SF are concentrated in District 6 area with only 10% of the population. Another area with 10% of the population, supervisor district 4, has only about 1% of the homeless. District 4, which is about as suburban as Palo Alto, has about the same homelessness rate Palo Alto does, which makes it hard to argue that this is about SF vs. Palo Alto policy differences.

Conclusion: No social phenomenon is ever caused by just one thing, but San Francisco’s homelessness rate is around where a housing-cost-based model would predict. San Fransicko briefly touches on this, but overall tries to de-emphasize it in favor of talking about drugs and mental illness. Critiques of patterns of emphasis are necessarily subjective, but the book’s pattern feels misleading to me.

Claim 2: Standard Accounts Underemphasize The Role Of Drugs And Mental Illness In Homelessness

Having argued homelessness isn’t just about poverty, the book goes on to say we’re neglecting the central role of mental illness and substance abuse:

Over the last decades there were many visible signs that homelessness was about much more than poverty and housing. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of calls made to San Francisco’s 311 line complaining of used hypodermic needles on sidewalks, in parks, and elsewhere rose from 224 to 6,275. In 2018, footage of dozens of people slumped over in an entrance to a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station, many with needles in their arm, went viral. “We call it the heroin freeze,” said one local. “They can stay that way for hours.” Said another, “It’s like the land of the living dead.”

For decades researchers have documented much higher levels of mental illness and substance abuse among the homeless than in the rest of the population. It’s true that just 8 and 18 percent of homeless people point to mental illness and substance abuse, respectively, as the primary cause of their homelessness, but researchers have long understood that such self-reports are unreliable due to the socially undesirable nature of substance abuse, and the lack of insight that often accompanies mental illness. Using other methods, San Francisco’s Health Department in 2019 estimated that 4,000 of the city’s 8,035 homeless, sheltered and unsheltered, are both mentally ill and suffering from substance abuse. Of those 4,000, about 1,600 frequently used emergency psychiatric services.

Shellenberger’s source for 4000 homeless people having these issues is this SF Chronicle article, which seems to based off of this report. The report does estimate 4000 homeless people with mental illness and substance abuse, but it uses a yearly rather than point estimate of homelessness, and finds 18,000 rather than 8,000 people. That means it only finds a 22% rate of these problems, not a 50% rate. Thanks to commenter Sean for hunting down this report and helping explain this.

I looked for other statistics to provide context on this number. This 2013 San Francisco Homeless Count found that 29% admitted chronic depression, 15% PTSD, and 22% some other mental illness. About 30% admitted to a substance use disorder, although as far as I can tell this is just the number who admitted it was a disorder, so maybe more used drugs.

This article by the Los Angeles Times describes an LA study finding that 25% of homeless people had mental health issues and 14% had drug issues. The Times re-analyzes it in a way that ups the numbers to 34% and 46%, respectively. But they don’t say exactly what choices they made differently, and the few they do give don’t really inspire confidence. Although in some cases they count questions clearly about mental illness which the official definition inexplicably refused to count, in others they decide to count anyone who has ever had mental illness, reversing a government decision to require the mental illness to be long-term (does this mean that if I lost my house tomorrow, the LA Times use me as an example of a “mentally ill homeless person” because I saw a psychiatrist for OCD when I was a kid?)

Studies like these don’t show causation. Sure, mental illness can make people homeless. But homelessness can also cause mental illness. One SF study found psych diagnoses among the homeless to be evenly divided among depression, PTSD, and everything else. Homelessness is a depressing and traumatic environment. Just because someone who’s been on the streets for a year has depression or trauma, doesn’t mean that we should attribute their homelessness to mental illness.

This study by the California Policy Lab does better. It asks what factors played a role in homeless people losing their homes, and finds that 50% of unsheltered and 17% of sheltered homeless point to mental illness (given SF’s balance, that suggests 37% of SF homeless would point to that problem). But I can’t help but notice that when you add up the percent of people who lost their homes due to physical illness, psych illness, and drug use, it totals 147%. Based on numbers from other studies, it looks like if you added in job loss, eviction, etc, the numbers would total well above 400%. This makes me think people are saying “yes” if the factor played even a minor role in their eventual homelessness, and this shouldn’t be treated as 37% of homeless having mental health issues being their main problem. The same study finds that about 66% of the homeless “have” some mental health problem, but this time they don’t tell us what question they asked or what criteria they use.

What about psychosis in particular? This meta-analysis claims that in developed countries (a category to which San Francisco still nominally belongs) about 19% of homeless people qualify for diagnosis with a psychotic disorder, including 9% with schizophrenia in particular. Not all people with psychotic disorders are completely crazy all the time, and some very much are not, but this is at least a specific condition with real criteria.

Conclusion: Overall, I’m disappointed in most of the published research on this question, which seems more interested in producing glossy brochures about funding disparities than in informing anybody what any of their numbers mean. But putting it all together and squinting really hard, I think we can tell a story where 10-20% of the homeless are seriously psychotic, and another 20-30% have contributing mental health conditions including depression, PTSD, and others. Somewhere between 25% and 50% of the homeless have substance abuse problems, and this probably mostly overlaps with the 25% - 50% who have psych diagnoses. I think San Fransicko gets this mostly right.

Claim 3: “Housing First” Isn’t As Great As People Think, And Might Be Harmful

The National Myth About Homelessness is that The Bad People are refusing to give people houses until they’ve “proven” they “deserve” them, thus perpetuating homelessness when they inevitably fail to qualify. The Good People have united under an exciting new banner called “Housing First” to push the revolutionary idea that people should get houses regardless of whether they conform to normal standards of respectability or not. Wherever this is adopted, homelessness rates fall, and the formerly homeless becoming healthier, safer, and more likely to re-integrate into society. Best of all, the program pays for itself in decreased health care and policing costs. The only impediment to solving homelessness everywhere is the Bad People who still insist on not housing the homeless until they’ve “earned” it.

In real life, everyone important has been united under Housing First since the Bush administration made it national policy fifteen years ago, and most of the cities with spiraling homelessness crises have been pursuing Housing First policies for decades (eg San Francisco has been trying Housing First since the 1990s). The Obama and Trump administrations both set funding policies that penalized any non-Housing-First welfare programs.

Still, everyone is sure that the reason there are still homeless people must be that some Housing First opponent still exists somewhere, ruining everything with their purity-testing ways. But actually these people have already been relegated to the conservative think tanks where moribund ideas go to die.

I have looked through a lot of studies and articles to try to see how well Housing First works. I am most sympathetic to the conclusions of Tsai (2020), who basically says that:

Homeless people who are given houses are more housed than homeless people who are not given houses. Way, way more housed. You would not believe how strong of an effect giving someone housing has on them being housed. The same is true for other outcome measures like “time spent experiencing homelessness”, “number of days spent in a temporary homeless shelter”, etc. You might think this is obvious, but this is used as the primary outcome in a lot of studies, and “success” on this metric is behind a lot of claims that “studies show Housing First works great!”

Tsai describes “moderate” evidence showing that Housing First decreases emergency services utilization, based mostly on this meta-analysis, which admits that all of its studies have “high risk of bias”.

“There is no substantial published evidence as yet to demonstrate that PSH [permanent supportive housing] improves health outcomes or reduces healthcare costs. The one exception is a randomized trial of Housing First that found improved health outcomes for patients with HIV/AIDS.”

Tsai also comments that (like in psychiatry) any intensive and well-thought-out housing program is better than nothing (“treatment as usual”, in medical lingo). This is also the conclusion of this giant review on homelessness interventions, which classifies Housing First as “high-quality” but gives the same honor to its direct opposite, abstinence-contingent housing. Either intervention beats doing nothing, or doing some vague unprincipled collection of whatever services are available at the time. But the few studies that compare them head-to-head do find Housing First doing better (1, 2), albeit usually with significant risk of bias.

What about costs? I was able to find two meta-analyses. Ly and Latimer (2015) find that Housing First saves money on net (ie even after paying housing costs) in nonrandomized studies, but not in higher-quality true experiments. However, even in the latter group, it comes close to doing this, so that governments successfully house the homeless for much less than the cost of housing would suggest. Jacob et al (2022) find that benefits do exceed costs, estimating benefits of 1.8x cost in all studies, 1.3x cost in higher-quality studies, and about 1.05x cost in the best studies.

I found Basu et al helpful in breaking down what was going on here. They have a great table of their assumptions about costs:

…and find that:

Those in the intervention group incurred 2.6 fewer hospitalized days (p = .08), 1.2 fewer emergency room visits (p = .04), 7.5 fewer days in residential substance abuse treatment (p = .004), 9.8 fewer nursing home days (p = .08), and 3.8 more outpatient visits each year (p = .01) annually compared with those in the usual care group. Those in the intervention group had 7.7 fewer prison days during the study period (p = .07). Those in the intervention group had 62 more days in stable housing (p = .001) and 12 more days in respite care (p = .002) than those in the usual care group. Those in the intervention group used case management services (i.e., telephone calls and face-to-face meetings) more frequently than those in the usual care group, having on average 18 more encounters per year (p < .001).

This study provided case management along with the free housing. I don’t know whether to think of that as a confounder, or a standard aspect of Housing First programs (especially since it is much harder to case manage someone with no fixed address).

Notice that it assumes the cost of housing is given as $30/day. I think this is realistic for low-income housing in Chicago, but other California programs I’ve looked at have worked out to more like $70 - $100/day, which (assuming nothing else changed) would switch the conclusion of this study from “Housing First saves money” to “Housing First costs money”.

Now let’s see what San Fransicko has to say:

The evidence for Housing First turns out to be significantly weaker than its proponents suggest. For example, the much lauded initiative to reduce homelessness among veterans was only four percentage points more successful than the overall decline in homelessness, when accounting for age, which is necessary to accurately estimate what is due to policy and what is due to demographic changes. As for Utah, its legislative auditor general concluded in 2018 that the 91 percent number was wrong, based on a sloppy use of incorrect methodologies. Before 2015, Utah had annualized its homeless count, meaning that researchers counted the homeless at a single point in time and multiplied the data by some factor. But after 2015 the state used raw point-in-time counts, causing a precipitous drop in the official population counts. Over the same period, the state also narrowed its definition of chronic homelessness in several ways, resulting in further apparent reductions. In reality, the homeless population in Utah increased by 12 percent between 2016 and 2020.

An experiment with 249 homeless people in San Francisco between 1999 and 2002 found those enrolled in the city’s Housing First program, Direct Access to Housing, used medical services at the same rate as those who were not given housing through the program, suggesting that the Housing First program likely had minimal impact on the participants’ health. Wrote a team of researchers, “obtaining housing does not necessarily resolve other issues that may impede one’s housing success,” pointing to the lack of significant improvements in substance use and psychiatric symptoms over the twelve months that people were housed (the share of patients with severe substance use actually saw a modest increase).

The problem with Housing First stems from the fact that it doesn’t require that people address their mental illness and substance abuse, which are often the underlying causes of homelessness. Several studies have found that people in Housing First–type housing showed no improvement in drug use from when they were first housed.

In 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a review of the scientific literature of Housing First. “On the basis of currently available research,” the report’s authors wrote, with some surprise, “the committee found no substantial evidence that [permanent supportive housing] contributes to improved health outcomes, notwithstanding the intuitive logic that it should do so and limited data showing that it does do so for persons with HIV/AIDS.”

Tsemberis said he was not surprised by the findings of the National Academies. “It’s not like housing creates improved health,” he said. “You have to have a relationship with a nurse. You have to be educated on what your health problems are. You have to have a team that engages you and makes you an active participant in your own health care. I don’t even know if that would stop the number of deaths.” And, at least in the study funded by Benioff and conducted by Margot Kushel, which had those services, it did not.

All of this seems to fit with what I found above. But:

Housing First may even increase addiction and overdose deaths and make quitting drugs more difficult. Warned a multiauthor review in 2009, “One potential risk [of Housing First’s harm reduction approach] would be worsening the addiction itself, as the federal collaborative initiative preliminary evaluation seemed to suggest.” The authors pointed to an experiment that had to be stopped and reorganized after the homeless individuals in the abstinence group complained of being housed with people in the control group, who didn’t stop their drug and alcohol use. “They claimed that they preferred to return to homelessness rather than live near drug users.”

The multiauthor review cited is Housing First For Homeless People With Active Addiction: Are We Overreaching? They write: “It would be premature to conclude that Housing First programs cannot accommodate persons with severe addiction. But it also would be premature to suggest that research data provide clear guidance on whether, or how, Housing First programs can accommodate persons with ongoing severe drug and alcohol abuse. In the absence of research data on this subject, it is reasonable to consider the kinds of risks that may occur in Housing First programs. One potential risk would be worsening the addiction itself, as the federal collaborative initiative preliminary evaluation seemed to suggest (Mares, Greenberg, and Rosenheck 2007), or failing to progress toward addictive recovery.”

Elsewhere, they describe this same study as: “The eleven-site federal collaborative initiative found an association between early access to housing and increases in alcohol problems during the subsequent year”

The study is here, but I can’t find this result anywhere. It describes its own results (my emphasis) as:

The average number of days housed in the previous 90 days increased dramatically from 18 at baseline, to 68 at the 3-month follow-up, and rose steadily thereafter to 83 at the 12 month follow-up (Table 2). Mean monthly public assistance income increased steadily from $316 at baseline to $478 one year later, a 50% increase. Significant improvements of modest magnitude were also observed in overall quality of life, mental health functioning, and reduced psychological distress. Alcohol and drug problems remained largely unchanged over time. Total quarterly health costs declined by 50%, from $6,832 at baseline to $3,376 at 12 months. A 54% decrease in mean inpatient costs ($5,776 to $2,677) accounted for nearly 90% of the overall decrease in quarterly health care costs during clients' first year in the program

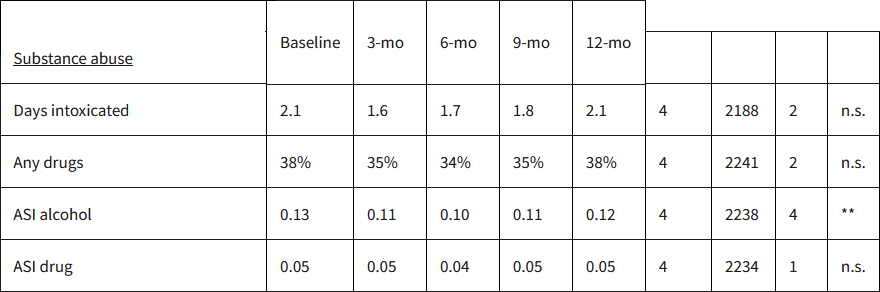

And the table (slightly edited for readability):

I might be misunderstanding this - I can’t imagine why the authors of the review would have gotten this wrong - but it does look to me like alcoholism stayed steady throughout this study.

A 24-month followup of what I think is the same study also finds that drug users who were housed used slightly fewer drugs over time, although probably not to any significant degree worth caring about:

Continuing from San Fransicko:

There is evidence that privacy and solitude created by Housing First make substance abuse worse. A study in Ottawa found that, while the Housing First group kept people in housing longer, the comparison group saw greater reductions in alcohol consumption and problematic drug use, and greater improvements to mental health, after two years. “One reason for the surprising results,” wrote the authors, “may be that aspects of the Housing First intervention, such as the privacy afforded by Housing First and harm reduction approach, might result in slower improvements around substance use and mental health.”

Okay, but the next sentence after the one the book quoted was the researchers admitting that oops, we also totally forgot to randomize our groups in any way, so the experimental and control groups had totally different levels of severity and maybe that was why they found this weird thing (this is non-obvious, because we’re looking at change over time rather than raw differences between groups, but the authors discuss some reasons why different groups might change differently over time). A few years later these same researchers did a proper randomized study and it found no difference in drug use between the two groups.

Somers, Moniruzzaman and Palepu found no difference in drug use between Housing First and other subjects. Padgett et al found the Housing First group actually did better, although they are another victim of the epidemic of randomization failures in this space. Kirst et al, no difference in drug use, but Housing First better with alcohol. Milby found that housing contigent on abstinence worked better than housing not contigent on abstinence, which Shellenberger could have used to support his thesis, but even Milby found that housing not contingent on abstinence worked better than no housing!

To summarize: I can find seven studies on this topic, only one of them agrees with San Fransicko’s thesis, and the authors admit that it’s weak. I accuse San Fransicko of citing only that one and pretending all the others don’t exist.

(actually, I accuse it of doing that plus citing a line from a review claiming another study found this, but as far as I can tell that study did not actually find it)

This is extra annoying, because all the popular news articles on Housing First gush about how it definitely decreases substance use and everything else bad. Shellenberger could have made the excellent point that all of these progressive journalists were totally wrong! This would have been an interesting, important, and completely true act of virtuous data journalism! Instead he tries to hold up a lonely negative result as representative, and ends up just as wrong but in the opposite direction.

Continuing in San Fransicko:

Researchers have found ways to use housing to reduce addiction. Between 1990 and 2006, researchers in Birmingham, Alabama, conducted clinical trials of abstinence-contingent housing with 644 homeless people with crack cocaine addictions. Two-thirds of participants remained abstinent after six months, a very high rate of abstinence, compared to other treatment programs. Other studies found that around 40 percent of homeless in abstinence-contingent housing maintained their abstinence, housing, and jobs.

In a randomized controlled trial, homeless people were given furnished apartments and allowed to keep them unless they failed a drug test, at which point they were sent to stay in a shelter. Sixty-five percent of participants completed the program. Three similar randomized controlled trials also found moderate to high rates of completion. And participants in abstinence-contingent housing had better housing and employment outcomes than participants assigned housing for whom abstinence was not required.

All of this seems basically true.

It turns out that over longer periods of time, Housing First may not even outperform contingency in terms of keeping people housed. In the spring of 2021, a team of Harvard medical experts published the results of a fourteen-year-long study of chronic homeless placed into permanent supportive housing in Boston. Most studies of permanent supportive housing, including the Kushel study conducted in Santa Clara, only study the newly housed homeless for a span of around two years. The study found that 86 percent of the homeless, who were referred based on length of time living on the streets, suffered from “trimorbidity”—a combination of medical illness, mental illness, and substance abuse. The authors found that after ten years, just 12 percent of the homeless remained housed. During the study period, 45 percent died. The authors concluded that, because the chronically homeless had such higher rates of physical and mental illness, “the supportive services, essential to the PSH model, may not have been sufficient to address the needs of this unsheltered population.”

This study was done on an especially severe subgroup of homeless people. There was no control group, so Shellenberger shouldn’t claim we have any evidence about whether Housing First can “outperform contingency”. Shellenberger counts people who died as “unhoused” to get his 12% number; if he didn’t do this, the number would be 23%.

Only 23% of people given housing retained after ten years sounds bad. But you could change this number to whatever number you wanted by changing the severity of the subgroup selected for the study. Select people who are even crazier and more disturbed than these people, and you can have 0% retained after ten years; select high-functioning people with no problems, and you can get 100% retained after ten years.

(or maybe not - the study doesn’t say why people left the program. It mentions that one possible outcome is having to go to a nursing home because they had grown too sick or old to support themselves. I am not sure that “23% stay in this program” means “77% are back on the street and all their care has been a total failure”.)

Conclusion: Housing First seems to work in getting people housing. It probably also helps people use fewer medical services, and it might or might not save money compared to not doing it (probably more likely when treating very severe cases, less likely in areas with high housing costs). It probably doesn’t affect people’s overall health or drug use status very much. San Fransicko is right to call out all the people promoting it beyond what the evidence supports, but then goes on to attack it beyond what the evidence supports.

Interlude: Why Can’t We Just House All The Homeless?

This is the question many of the California gubernatorial candidates asked. California has lots of money. There aren’t that many homeless people. Everyone is already committed to Housing First. So why don’t they have houses already?

San Francisco has about 7,000 homeless people. The median SF apartment costs about $3,000 per month (presumably the government officials in charge would be trying to buy cheaper-than-median apartments for this project, but they seem bad at that, so let’s stick with median as a high-end estimate). So that’s $250 million/year to rent every homeless person an apartment. San Francisco has a $14 billion budget, although some of that is locked in nondiscretionary programs. So this effort would take about 2-3% of the city budget. Given how many people have both altruistic and selfish objections to the current level of SF homelessness, I can’t imagine that isn’t a better use of the money than whatever it’s being spent on now. So why hasn’t this happened?

The closest thing I can find to the “rent apartments” plan is Governor Newsom’s “rent hotel rooms” plan, Project Roomkey. This was a short-term pandemic program. This article says it cost $4,000 per month, which seems reasonable - it provided residents with a hotel room, meals, security, and “custodial services” for just above a hundred dollars a day. So how come nobody has made it permanent or scaled it up?

The homeless themselves don’t seem very positive on the project. They talk about “jail”-like conditions, including curfews and bans on visitors. I don’t know if this is the usual nanny-state-ism, or an attempt to reassure hotel owners / other residents / local communities that the influx of homeless people won’t cause them problems. If the latter, it hasn’t worked. From here:

Jenna Abbott, executive director of the River District Business Association, said having a Roomkey motel in her neighborhood has been difficult. The site — which is in an area with large number of unhoused people — has drawn family and friends of Roomkey residents who haven’t been housed but “camp close to that hotel,” some with the goal of gaining a room, Abbott said. That’s led to more loitering, public drunkenness and trash outside the restaurants, gas stations and other businesses in the area, she added.

And here’s another article about people objecting to local hotels accepting homeless people, which focuses on some combination of zoning, code, and public safety concerns.

Everybody - the homeless, their advocates, various experts - interviewed in the article - agrees that the hotel rooms are kind of dehumanizing and much worse than having real housing. And this article suggests that government budgeters believe it’s not cost-effective compared to alternatives. Since the homeless don’t like it, and it’s expensive, almost everyone seems to agree it made sense as a short-term COVID measure only.

The government’s preferred medium-term solution is single resident occupancy (SRO) hotels. These are big apartment/hotel-like structures where everyone has a small bedroom and then there are communal bathrooms and maybe kitchens. These used to be the archetypal living situation for poor Americans (Matt Yglesias talks about them as “boarding houses” here). But moral reformers banned them in the 1900s on the grounds that they were slums - I think this is the usual “surely the reason poor people live bad lives is because capitalists oppress them by selling them cheap low-quality goods, and if we just ban selling people cheap low-quality goods, everyone will have high-quality goods and poor people will live great lives!” argument. Somehow this failed to work and homelessness got worse over this period, but there are still some SRO hotels left, and the government got them and converted them to public housing for homeless people.

Shellenberger does not have high opinions of these:

The Tenderloin [district of San Francisco]’s single resident occupancy hotels . . . have for decades been dominated by a culture of heavy substance use and prostitution. “Of the people in supportive housing in San Francisco, 93 percent have a major mental illness that we can name,” said a housing policy maker. “That is very, very high. Eighty percent use cocaine, speed, or heroin every thirty days, or get drunk to the point of unconsciousness.”

Tom Wolf, a former Salvation Army caseworker and a member of San Francisco’s Drug Dealing Taskforce, says the city’s supportive housing facilities are themselves a major market for illegal drugs. “Go down the street to the Camelot Hotel on Turk Street,” said Wolf. “Almost everyone that I’ve seen in those hotels are using. The last front desk guy that was working there got busted because he was selling crack. The actual guy that works in the single resident occupancy hotel is selling crack! It’s insane, man.”

In any case, there are only so many of these still left. The government often announces plans to buy defunct regular hotels and convert them into these structures, which would indeed be a medium-term solution for housing the homeless, except that they usually get bogged down in fights about code.

Politico discusses one of these attempts in New York City (h/t Marginal Revolution):

“There are very few hotels that physically could be converted and comply with the requirements of today’s zoning and building code without substantial, expansive reconstruction, partial removal or demolition,” said James Colgate, a land use partner at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP who has advised clients on zoning issues including the conversions of hotels. “That would increase the costs greatly.”

For example, a building’s elevators, doorways, or rooms may be slightly short of the size required for a residential structure. Residential buildings are also required to have a certain amount of rear-yard space that a hotel may not have.

“You would literally have to be chopping off part of the building,” Rosen said.

…The legislation dictates that each unit include a kitchen or kitchenette with a full-sized refrigerator, cooktop and sink — something Rosen said made utilizing the program “simply too expensive.”

“This is the classic case of the perfect being the enemy of the possible,” said Mark Ginsberg, a partner at the firm Curtis + Ginsberg Architects, which has worked on hotel conversions.

Some advocates who pushed the creation of the program say those provisions were necessary to ensure it didn’t generate substandard housing […]

“We didn’t want a program that cut corners to make it more palatable to developers,” said Joseph Loonam, housing campaign coordinator for the progressive advocacy group VOCAL-NY. “We wanted a program that centered the needs of homeless New Yorkers, which is true high quality affordable housing where they can have full autonomy and dignity.”

As Marginal Revolution pointed out, Loonam got what he wanted; the expensive, over-regulated program was unpalatable to developers, with only one company putting in an offer; for whatever reason, NYC refused to go with that one company, and no housing was produced.

But fine, these are also terrible, and they’re only medium-term solutions anyway. What about building real, long-term apartments for homeless people?

Shellenberger tells the story of Los Angeles’ Proposition HHH, which raised $1.2 billion to do exactly this. They hoped to build ~10,000 units for the homeless, at a projected price of $140,000 each; since LA had about 30,000 homeless people at the time, this would solve a third of the problem - a good start.

(how do these numbers line up with my back-of-the-envelope calculation for SF above? I talked about renting rather than building, but usually annual rents = 1/20th or so of total prices, so I was estimating about $700,000 per person. This is probably partly because SF costs more than LA, and partly because I was imagining median apartments whereas LA is probably working on very cheap apartments)

But in fact, five years later, LA has completed only 700 units, and the cost per unit has spiralled to $531,000 each. Nobody has a good explanation for what happened, with Shellenberger quoting one local service provider who said a lot of it was “bullshit costs”. Now might be a good time to re-read Considerations On Cost Disease.

[Update: this might not be accurate - see this comment]

This seems to be a general problem: everyone is committed to Housing First and to long-term good solutions rather than short- or medium- term mediocre ones. But that means building housing. And some combination of NIMBYism and over-regulation means building housing is somewhere between ruiniously expensive and impossible.

Claim 4: Shelters Are Unpopular Among Progressive Activists And The Homeless Themselves

San Francisco doesn’t have more homelessness than eg New York, but almost all the homeless in New York live in shelters and stay off the street. Why doesn’t that work here?

Shellenberger:

In the context of cities with permissive attitudes toward drugs, like San Francisco, many homeless people stay in [tent] encampments to use illegal substances more freely and easily than they can in the shelters. Many policy makers understand this. “I went out with a team twice to have conversations with people to get an understanding of what they’re dealing with,” said Mayor Breed in 2020. “It was absolutely insane. Most of the people did not take us up on the offer [of shelter and services].”

Even people who would prefer to live in sober environments say they do not want to quit their addictions. “When we surveyed people in supportive housing in New York,” said University of Pennsylvania homelessness researcher Dennis Culhane, “almost everybody wanted their neighbors to be clean and sober but they didn’t want rules for themselves about being clean.”

In 2016, after the city of San Francisco broke up a massive, 350-person homeless encampment, dozens of the homeless refused the city’s offers of help. Of the 150 people moved during a single month of homeless encampment cleanups in 2018, just eight people accepted the city’s offer of shelter. In 2004, just 131 people went into permanent supportive housing after 4,950 contacts made by then-mayor Newsom’s homeless outreach teams.

An article by a former homeless person explains the problems with shelters beyond just “can’t use drugs”. Residents are crammed into a small space with 300 other homeless people. Lice and bedbugs are everywhere. Everybody catches every disease. Everybody has stories about getting raped or beaten up. Invasive moralizing about drugs somehow exists side by side with rampant drug use.

Shelters are gender segregated, which means straight people can’t stay with their partner. Most shelters ban children and nobody has any idea what to do with them. Most shelters ban pets - a lot of homeless people have dogs for protection or companionship, and you can’t just store them somewhere while you’re sheltering.

Although some lucky people can get 90-day beds, other people need to apply for beds on a day-by-day basis, which requires waiting in line several hours every day. Users talk about rampant cutting in line, denying cutting in line, false accusations of cutting in line, etc. Most shelters kick people out between 9-5, either to save on staffing costs or in the hopes that they’ll get a job. But many have strict curfews requiring people to be back by 5 PM sharp, which can make jobs impossible - if your boss doesn’t let you out until 5 and you have a half-hour commute, how do you get back to the shelter on time?

But even the homeless people who do want to go to shelters mostly can’t get in.

This app gives the current status of San Francisco’s homeless shelter waitlist. If you applied today, there would be 900 people ahead of you in line for one of the city’s 1500 - 2500 shelter beds. The app says that the median wait time is 826 days.

So however many homeless people don’t want to go to shelters, we’re not building enough shelters to serve the ones who do. Why not? Shellenberger again:

In the spring of 2021, Friedenbach published an op-ed opposing a proposal considered by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to create, within eighteen months, sufficient homeless shelters and outdoor “Safe Sleeping Sites” for all of the city’s unsheltered homeless. “One can simply take a look to New York City,” she wrote. “Their department spends about $1.3 billion dollars of its budget on providing shelter for their unhoused population while thousands remain on the street. . . . As a result, New York has a higher rate of homelessness than San Francisco.”

Housing First advocate Margot Kushel of the University of California, San Francisco agreed. “The problem with New York—and I spend a lot of time with people working in the system in New York—is that they spend an estimated $30,000 for each person per year to keep them in shelter. That’s not what we want to do. Because if you create the shelter and you don’t create the housing, then people are just in shelter forever.”

Housing First advocates oppose shelter in Los Angeles. “Why haven’t we solved homelessness?” asked Housing First creator Sam Tsemberis. “Because [Los Angeles mayor] Eric Garcetti [has] Andy Bales [saying,] ‘You need emergency housing.’ ‘These people need to be cleaned up.’ ‘They need to be sober.’ ‘They need Jesus before they’ll be ready for housing.’ I said, ‘People should be housed and then maybe they’ll get sobriety and Jesus and the rest.’ We’re definitely on polar opposites of the whole thing.”

Advocates for the homeless at the national level similarly oppose more shelters. “I don’t agree that we should be building more transitional housing,” said the head of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. […]

In other words, the reason that there are so many homeless people on the streets in San Francisco is that both progressive and moderate Democratic elected officials, and the city’s most influential homelessness experts and advocates, have for two decades opposed building sufficient shelters. And that is unlikely to change even after San Francisco starts spending hundreds of millions more per year on the problem and might even get worse.

This basically seems true. I found this webpage of a former SF Supervisor candidate a helpful corroborating source. He was running on a platform of “maybe we should build some homeless shelters”. He lost. You can also find a bunch of webpages by the sorts of people Shellenberger is complaining about, for example this site:

Sup[ervisor] Rafael Mandelman today pushed his new legislation that would require the city to offer at least temporary shelter to everyone living on the streets, a step that some say would lead to more homeless sweeps and do nothing to create permanently affordable housing . . . [our] Coalition has argued for years that the solution to homelessness is housing—not temporary shelter, which may never lead to housing.

The ex-supervisor candidate gives some helpful numbers: permanent housing costs about $600,000 per person housed. Shelters cost between $20,000 and $30,000 per person housed. So SF could build enough shelters to clear its waitlist for about $30 million.

More recently, SF has tried a sort of compromise, opening “deluxe” shelters called Navigation Centers which avoid some of the problems of regular shelters. They also cost more than twice as much, and the city has only created about 300 beds. Also, the people in regular shelters are angry, because being in a regular shelter disqualifies you from getting into a (much better) Navigation Center. Some of them are considering leaving their shelter, going back on the streets, then waiting however many months or years it takes to get a Navigation Center bed instead.

I’m not at all sure of these numbers, but it looks like of SF’s ~7,000 homeless, about 2,000 are in shelters already, and 1,000 are on the shelter waitlist. I don’t know if the remaining 4,000 have made a specific commitment not to go to shelters, or just have given up on the waitlist process.

My conclusion: agree with San Fransicko about the role of progressive activists, but I think it overemphasizes the role of wanting to use drugs in why homeless people themselves sometimes avoid shelters, and underemphasizes the many other problems with them.

Claim 5: Drug Decriminalization Isn’t Working

California legalized marijuana in 2016. Shellenberger says that San Francisco’s commitment to drugs has gone beyond that: it has effectively decriminalized opioids, cocaine, and the rest. Any attempt to lessen use of these drugs is attacked as “stigmatizing”; instead, government policy centers around providing addicts with needles and other drug paraphernalia under the guise of “harm reduction”.

Shellenberger hits all the right beats here. Like many people, he tries to undo the damage done by The New Jim Crow, a book which convinced millions of people that mass incarceration was driven by a racist War On Drugs. In fact, less than a fifth of prisoners are in for drug-related crimes. And when the government was first debating the War on Drugs and mass incarceration, black leaders were among the strongest proponents of both. The talking point at the time - among everyone from black Congressional leaders to black churches - was that the government’s failure to crack down on drug use was racist, borne of them not caring about predominantly black drug victims.

And while we’ve been patting ourselves on the back about how enlightened we are for ending the drug war:

Drug overdoses are today the number one cause of accidental death in the United States as a result of America’s historic addiction and overdose epidemic. Overdose deaths rose from 17,415 in 2000 to 93,330 in 2020, a 536 percent increase.Significantly more people die of drug overdoses today than of homicide (13,927 in 2019) or car accidents (36,096 in 2019). […]

There are about twenty-five thousand injection drug users in San Francisco, a number 50 percent larger than the number of students enrolled in the city’s fifteen public high schools. San Francisco gives away more needles to drug users, six million per year, than New York City, despite having one-tenth the population.

The part of this chapter that stood out to me as most worth looking into deeper was the section on Portugal:

For decades, harm reduction and decriminalization advocates have pointed to Portugal as a model, noting that it decriminalized drugs and expanded drug treatment. In 2013, Portugal’s drug-induced death rate was sixty-six times less than that of the United States. The number of people in treatment increased by 60 percent between 1998 and 2011, with three-quarters receiving an opioid substitute like methadone or Suboxone, the brand name of buprenorphine. Drug use among 15- to 24-year-olds actually declined after decriminalization. “All drugs have been legalized,” explained Monique Tula, executive director of the Harm Reduction Coalition. “Their focus is on giving people tools, like job apprenticeships, and the means to support themselves.” […]

[But Portugal] never legalized drugs. It only decriminalized them, reducing criminal penalties but maintaining prohibition. Drug dealers were still sent to prison even after the 2001 decriminalization. And Portugal does not let people addicted to hard drugs with behavioral disorders off the hook like progressive West Coast cities have done. It’s true that Portugal massively expanded drug treatment, but people are still arrested and fined for possession of heroin, meth, and other hard drugs. And drug users are typically sent to a regionally administered “Commissions for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction,” composed of a social worker, lawyer, and doctor who encourage, push, and coerce drug treatment.

And decriminalization doesn’t end drug violence. “Even if trafficking enforcement decreased, like it did in Portugal,” said criminologist John Pfaff, “illegal drug markets would still be forced to rely on violence to resolve disputes.” Indeed, prostitution and violence are ever-present in the open-air drug scenes in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle. “We are seeing behaviors from our guests that I’ve never seen in thirty-three years,” said Rev. Andy Bales, who runs the largest homeless shelter on Skid Row in Los Angeles. “They are so bizarre and different that I don’t even feel right describing the behaviors. It’s extreme violence of an extreme sexual nature.”

People are not dying from drug overdose deaths in San Francisco because they’re being arrested. They’re dying because they aren’t being arrested. Decriminalization reduces prices by lowering production and distribution costs, which increases use. This was also the case for alcohol consumption. It increased after prohibition ended in the United States. Even in Portugal, drug overdose deaths and overall drug use rose after decriminalization.

I was most surprised by the claim that Portuguese overdose deaths rose after decriminalization. Uncharacteristically, San Fransicko doesn’t give a citation for it, but we can try to retrace its reasoning.

Decriminalization proponents tend to point to these numbers, helpfully converted to per 100,000 population and graphed here:

But an anti-drug Australian think tank argues that the peak in 2001 is made up:

Claims that there were more than 75 drug-related deaths in 2001 which more than

halved to 34 deaths in 2002 use a figure for 2001 for which there is no substantiation. Official drug-related deaths for Portugal, taken from the latest 2018 EMCDDA Statistical Bulletin are copied below. Notice that there is no such figure recorded for 2001.

They include a link to EMCDDA, the EU organization charged with monitoring these things. The link contains two datasets, both of which seem to be measuring the same thing but getting different results. One dataset starts in 2002, the other in 2008. I don’t know what the difference here is, but they’re right that neither includes 2001. If you ignore the pre-2002 data, the graph looks like this:

But the proponents link to the updated 2020 version of the same website, which all of a sudden does have data from 2001 and before. I don’t know why EMCDDA can’t make up its mind, but I think the Australians are wrong and the original graph is fine.

On the other hand, does it really matter? Both of these show drug deaths decreasing until 2005, then going up and down a bit, then going back up again starting in 2011. I think a reasonable interpretation would be that decriminalization in Portugal did decrease overdose deaths a bit, and then they started rising again from that low baseline around the same time other European countries saw rising overdose deaths. I would also accept “these are pretty small effects and we shouldn’t ascribe any significance to them”.

But San Fransicko’s claim - that overdose deaths increased after the reform - seems false. The only way I can see justifying it is taking the second graph - the one that wrongly claims there is no pre-2002 data - and then attributing the fact that twelve years after the reform lowered deaths, deaths finally rose above the pre-reform level to be the fault of the reform. This is like saying “people claim the Black Plague killed a lot of Europeans, but the European population actually rose after the Plague”, which is true in the sense that it was above its pre-Plague max by like 1600 or whatever.

What about overall drug use? Here I recommend A Resounding Success Or Disastrous Failure: Re-examining The Interpretation Of Evidence On The Portuguese Decriminalisation Of Illicit Drugs, which is on exactly this topic of how people keep selectively quoting results from Portugal to prove their point. It argues that drug use is inherently hard to measure. There are four different Portuguese datasets for the time at issue, lots of different drugs, lots of different age/gender combinations, and lots of different ways of measuring drugs (did you use drugs in the past month? the past year? your lifetime?) It’s easy to tell a story of how past-month cocaine use skyrocketed among 14-29 year old males according to X source, or how lifetime marijuana use fell in high school-age women according to Y.

The main trick that opponents use is measuring lifetime drug use. Portugal is a very conservative country; drug use is pretty new and most of the older generation wasn’t involved. So as time goes on and more and more people try drugs but “un-trying” drugs isn’t a thing, the percent of the population who have tried drugs inevitably goes up. This definitely happened but isn’t a fair reflection of any specific reform.

The authors find that in the past decade or so, there has been a bit more short-term experimentation with drugs, but less long-run use. They conclude:

As shown in Figure 2, general population (aged 15–64) trends for recent and current drug use in Portugal indicate minimal if any changes between 2001 and 2007. Instead, rates of discontinuation of drug use (the proportion of the population that reported ever having used a drug but opting not to in recent years) increased, which reinforces that just as in the school populations, the growth in lifetime-reported use reflected predominantly short-term experimental use. Increases in recent and current drug use were more notable in some cohorts, particularly those aged 25 to 34 (albeit, with a maximum of 7% of any one cohort reporting recent use, absolute levels remained low). But as shown in Figure 3, recent and current drug use declined among those aged 15–24, the population who were most at risk of initiation and long-term engagement. The available evidence thus gives grounds for arguing that while there was some growth in the scale of drug use in post-reform Portugal, there was an overall positive net benefit for the Portuguese community.

What about San Fransicko’s main point - that as the US has wound down the War on Drugs, drug overdose rates have sextupled?

I think this is mostly not causal. I think the sextupling of overdoses is a combination of expansion in prescription opioid use, various forms of social decay making people less happy and therefore more likely to use drugs, and “improvements” in drug “technology” and the “supply chain” (eg production of fentanyl in China). I don’t know of any source that attempts to tease out the exact contribution of all of these things, but I would note that overdose deaths have risen the most in very conservative Midwestern states that haven’t walked back the drug war as much as California.

Conclusion: As usual, I appreciate San Fransicko’s corrections to the prevailing narrative, but its own additions are dubious. Its claim that Portugal saw increased drug-related deaths seems false as far as I can tell. Its claim that it saw increased drug use depends on your definition, but is misleading and not the most natural way to sum up the evidence.

Claim 6: San Francisco’s Soft-On-Crime Policies Led To Rising Crime

Ten years ago, the news was full of stories about how some teenager stole a gumdrop and was sentenced to nine hundred billion years in jail. At some point, there was a genre shift to stories about how some hardened criminal murdered fifty people with an axe and the judge let him go with a warning because having jails felt racist.

How suspicious should we be of each type of story? There will always be an extreme right tail of overly harsh sentences, and an extreme left tail of overly lenient ones. Were the 2000s really as draconian as they felt? Is the modern era really as pathetic? Or is it all just a function of who you read and what agenda they’re pushing?

Shellenberger:

During California governor Jerry Brown’s time in office, voters passed several reforms aimed at reducing the size of the prison population. In 2012, voters passed a change to the Three Strikes law so that the third strike imposes a life sentence only if the new felony was serious or violent. In addition to lowering punishments for drug possession, Proposition 47, which voters passed in 2014, redefined shoplifting, forgery, petty theft, and receiving stolen property as misdemeanors when the value in question does not exceed $950. In 2016, voters approved a proposition that shortened the time it took for some nonviolent offenders to be eligible for parole and which released nonviolent offenders into drug treatment and rehabilitation.

Property crimes rose in San Francisco starting in 2012. Larceny, which is shoplifting and other petty theft, rose 50 percent, from roughly 3,000 incidents per 100,000 people in 2011 to about 4,500 in 2019. Property crimes as a whole, which include larceny, motor vehicle theft, and burglary, rose from 4,000 incidents per 100,000 people in 2011 to 5,500 in 2019. One study suggests that Proposition 47 increased the rate of auto theft 17 percent and the rate of larceny (non-auto property) theft 9 percent, but discerning between causation and correlation may not be possible.

Upon taking office in January 2020, [famously soft-on-crime San Francisco district attorney Chesa] Boudin followed through on his campaign promises. Instead of prosecuting and incarcerating people for breaking car windows to steal money and other items from inside, Boudin proposed creating a $1.5 million fund to reimburse car owners. But there were over 25,000 car break-ins reported in 2019. If every break-in cost just $250 in repairs, the fund would need four times that amount. And what would prevent people from falsely claiming to have been robbed in order to get city money? […]

Boudin opposed efforts by the mayor and the city attorney to prevent drug dealers who had already been arrested from entering the Tenderloin. “Until the city is serious about treating addiction and the root causes of drug use and selling,” said Boudin in a statement, “these recycled, punishment-focused approaches are unlikely to succeed at doing anything more than making headlines.”

Home burglaries rose in early 2021 in San Francisco. Homeowners started posting on Twitter videos from their security cameras of people breaking into homes and garages. “When I first moved here we had a car break-in problem,” said Michael Solana, a writer who works for a venture capital fund. “Now we have a home invasion problem. These things are wearing on people.” Boudin attributed the rise of burglaries in San Francisco to the decline of tourism and “people in desperate economic circumstances.” Progressive supervisor Hillary Ronen agreed. “We know that [economic insecurity and inequality] is one of the root causes of property crimes specifically,” she said.

But Tom Wolf and others argued that the robberies were, like the shoplifting, done by people seeking money to buy drugs and feed their addictions. “The drugstores have been shoplifted to death and that’s all because of drug use,” said Tom. “I know. I used to do the same thing when I was out there. That’s what you do. You ‘boost.’ And then you go and you sell your stuff down at UN Plaza,” an open-air drug scene.

In a May 2021 city supervisors’ meeting, a representative from CVS called San Francisco “the epicenter of organized retail crime in the country” and claimed that 85 percent of the shoplifting is committed by organized theft rings. Police broke up one such ring in October 2020 and recovered $8 million of stolen merchandise.

The problem goes beyond property crime. Boudin declined to prosecute two men who went on to kill people. One man had been repeatedly arrested for stealing cars, despite having just been released from prison earlier in the year, and appeared to be abusing meth. On New Year’s Eve, 2020, the man killed two people while driving intoxicated. Police found inside of his car a semiautomatic handgun and twenty-three grams of methamphetamine. On February 4, another intoxicated driver killed a pedestrian in a stolen car. The San Francisco police had arrested him in October 2020 for possessing a stolen car, a tool for stealing cars, and what appeared to be meth. Boudin chose not to pursue charges. In December, the California Highway Patrol arrested the man again for driving a stolen vehicle under the influence. Again he was not prosecuted.

The accident victim, an immigrant from Kenya, and his wife had moved to San Francisco two weeks before the fatal crash. “I blame the DA,” said the widow of the victim. The suspect, she said, “was someone who was out in the public who shouldn’t have been in the public. It was completely avoidable.”

Tom said he could feel the difference on the streets. “Drug dealing is unabated and it’s not one guy, it’s fifty guys dealing fentanyl and meth,” he said. “And it’s going unabated because the district attorney says, ‘These are the nonviolent, quality-of-life crimes,’ and ‘I’m not going to prosecute them.’” [..]

District Attorney Boudin was offering weaker sentences than even defense attorneys were requesting, according to Vicki Westbrook of San Francisco. “There’s a defense attorney who said, ‘It used to be that I would argue for this deal in court with the DA but now I don’t say anything because the DA is going to offer me a deal better than what I would have suggested. Somebody shot up the street with an automatic weapon. The first offer was six months in jail or time served plus two years of probation or something. And then [the DA] said, “How about thirty days in jail?”’”

Vicki laughed. “You really can do anything in San Francisco,” she said. “If you do get arrested, chances are you’re going to be out of jail in less than thirty days for damn near everything except maybe killing somebody and maybe even then, too. It’s hard to say at this point.”

Taking each of these points individually:

Proposition 47

There are two good big studies on the effects of Prop 47, one by Public Policy Institute and one by some UCI criminologists. The PPI study finds that the proposition increased theft and car break-ins by about 10%. The UCI study finds the same, but notes that under different assumptions the effects wouldn’t quite obtain statistical significance. This seems a bit too much like post hoc trying to get rid of an inconvenient effect, plus an effect on the border of statistical significance is different from positively finding no effect. I think a reasonable interpretation is that theft and car break-ins rose about 10% because of the proposition, just as Shellenberger says.

Some pro-47 sites note that most states have some limit on how much you to have to shoplift before it’s a felony, and Prop 47 brought California closer to the national average, rather than turning it into an outlier.

Chesa Boudin

Chesa Boudin took office two months before the COVID pandemic began. Any attempt to separate the effect of Chesa Boudin from the effect of the pandemic is doomed. Shoplifting definitely plummeted when Boudin took office, but that’s because all the stores were closed. Murders definitely rose a little after Boudin took office, but that’s because that was also when the Black Lives Matter protests happened, which demoralized police and led to a so-far-permanent spike in murders nationwide. Percent of criminals caught definitely fell when Boudin took office, but that’s because various aspects of the justice system were closed for COVID (I will grudgingly entertain speculation that a further decrease in arrest rates from 2020 to 2021 may have been a genuine Boudin effect).

In the absence of any real way to judge his performance, I think San Fransicko’s points about Boudin are plausible, though speculative.

Shoplifting

This one is terrible.

There’s a surprisingly spirited debate here (some of you may have already read Applied Divinity Studies’ article). The debate is: everyone on the ground in San Francisco - store owners, security guards, customers, random citizens - say that shoplifting has increased massively over the past decade. But statistics mostly say it hasn’t.

Against this, seriously, everyone says that shoplifting has obviously increased. I had a patient who worked in shoplifting prevention, he told me - his psychiatrist! Who he had no reason to lie to! - that he was constantly stressed dealing with the shoplifting surge devastating the stores he covered. Here’s the San Francisco subreddit’s response to someone posting the data showing shoplifting hasn’t risen - it’s just a lot of people laughing hysterically.

What’s going on? I was able to find a different set of statistics that does seem to show a longer-term increase in shoplifting (source):

The very big spike at the end might be a change in reporting by one or two stores - you can find the argument here. But it does look like shoplifting went from about 125 incidents/month in the early 2010s to more like 250/month just before the pandemic.

Why is this graph so different from the other one? It looks like the top one came from the Department of Justice, and the bottom one came from SFPD. I’m not sure why these report differently.

When you multiply out by 800K people in SF, by 12 months/year, and 30ish days/month, the first graph corresponds to 4 shoplifting incidents per day, and the second to 6. As LouB’s analysis here points out, that seems suspiciously low for a city of 800,000 people where stores are constantly closing because of shoplifting. Maybe off by a factor of a few hundred from what we’d expect. LouB writes:

The SFPD report only references shoplifting offenses that required SFPD officers to prepare an incident report. That means either the shoplifter fought security, committed additional crimes, or stole more than $950 worth of items. It’s not that SFPD’s report is erroneous, it’s just not a representative statistic.

In a parallel statistic, SFPD only completes incident reports for traffic accidents when there is an injury. Therefore, thousands of noninjury accidents are handled civilly without SFPD reports the same way thousands of shoplifting offenses are handled without reports. An insurance company would not determine premium rates based solely on SFPD incident reports, nor should readers interpret SFPD shoplifting reports as anywhere near the total picture of the shoplifting epidemic in San Francisco.

(this would also explain why one or two stores changing their reporting policy can produce a spike equal to everyone else in San Francisco combined)

But comparing incident reports from 2010 to incident reports from 2020 should still be apples-to-apples, unless the likelihood of reporting any given incident changed in the meantime.

Did it? This news article quotes a San Franciscan who says that when they try to report shoplifting incidents, the cops tell them not to because “it doesn’t make a difference”. If cops say that now more often than they used to, it would make all these statistics meaningless.

(Applied Divinity Studies claims to have an argument that shows this can’t be true. It goes something like: if San Francisco was a better place to shoplift than its neighbors - eg Oakland - then shoplifters would leave Oakland to go to San Francisco, and we would see Oakland shoplifting rates falling. Oakland shoplifting rates are falling, but no more so than the rest of the state, so there can’t be increased tolerance for shoplifting in San Francisco. I find this dubious for many reasons. First of all, many of the same reasons shoplifting is up in San Francisco - like Prop 47 or soft-on-crime progressive policies - also apply to Oakland. Second, given that shoplifting fell massively everywhere because of the pandemic, it feels dubious to try to compare different cities; maybe one city had stricter pandemic lockdowns than others. Third, do criminals really shop around for friendly jurisdictions? If so, why are so many crimes like car break-ins, concentrated in “the bad part of town”? Why wouldn’t criminals leave the bad part of town for under-exploited areas with richer residents and less competition? Maybe criminals in fact aren’t very strategic or mobile? Maybe they don’t want to stand in the BART station and then take a half-hour train ride holding a bag of stolen goods?)

Maybe a better argument against this being true is how stable the shoplifting rates have been over time. Wouldn’t it be weird if (let’s say) a tripling of the real shoplifting rates was matched by a third-ing of the reporting rates (rather than a halving or a quartering or whatever)?

On the other hand, here’s Shellenberger with some helpful data:

Some of this is probably because of Proposition 47, which made some forms of shoplifting punishable with citation rather than arrest (but wouldn’t that be a clear discontinuity rather than a gradual trend?) But overall it sure seems like shoplifting is being taken less seriously, which might encourage people to report less. Another statistic I see is that only 2.3% of shoplifting cases result in an arrest; I don’t know how this is different from the graph above with numbers in the 30s; maybe it involves different levels of what makes something a “case”.

I accept that the data don’t consistently show a spike in shoplifting. But what’s the alternative? My patient who works in loss prevention in SF stores is lying to me? The nice elderly Chinese man who sold me my last pair of glasses and chatted to me about the rampant shoplifting in his mall was lying? The San Francisco police are lying? Walgreens pretends to be concerned about shoplifting as part of a dastardly plot to close a bunch of stores for no reason? Target and CVS pretend to care about shoplifting as part of a plot to restrict their stores’ opening hours for no reason? Every big store near me has suddenly gotten a security guard at the front as part of some corporate-sponsored jobs program?