Book Review: Arguments About Aborigines

...

I.

A thought I had throughout reading L.R. Hiatt’s Arguments About Aborigines was: What are anthropologists even doing?

The book recounts two centuries’ worth of scholarly disputes over questions like whether aboriginal tribes had chiefs. But during those centuries, many Aborigines learned English, many Westerners learned Aboriginal languages, and representatives of each side often spent years embedded in one another’s culture. What stopped some Westerner from approaching an Aborigine, asking “So, do you have chiefs?” and resolving a hundred years of bitter academic debate?

Of course the answer must be something like “categories from different cultures don’t map neatly into another, and Aboriginal hierarchies have something that matches the Western idea of ‘chief’ in some sense but not in others”. And there are other complicating factors - maybe some Aboriginal tribes have chiefs and others don’t. Or maybe Aboriginal social organization changed after Western contact, and whatever chiefs they do or don’t have are a foreign imposition. Or maybe something about chiefs is taboo, and if you ask an Aborigine directly they’ll lie or dissemble or say something that’s obviously a euphemism to them but totally meaningless to you. All of these points are well taken. It still seems weird that the West could interact with an entire continent full of Aborigines for two hundred years and remain confused about basic facts of their social lives. You can repeat the usual platitudes about why anthropology is hard as many times as you want; it still doesn’t quite seem to sink in.

If you want to know the exact contours of two hundred years of scholarly debates around Aborigines, Arguments About Aborigines - which is shockingly well-written for an academic book - is the text for you. It also had some unexpected answers to the original question: what are anthropologists even doing.

In the nineteenth century, anthropologists - buoyed by the success of Darwin’s theory of evolution - tried to invent grand Theories of Everything about the rise of humankind. These usually looked like “All savages originally did P, then passed through intermediate stages where they did Q, R, and S sequentially, and finally reached the light of civilization where they did T”. We still remember some of these fondly: the classic motif of a caveman clubbing a random woman and dragging her off to be his wife comes from a real theory by anthropologist John McLennan that this was the original marriage ritual of humankind, with advanced cultures eventually adding epicycles like “consent” and “courtship”. There is still dim cultural awareness of James Frazier’s The Golden Bough, which purports to prove that all religion came from an ur-ritual of killing the king to ensure the fertility of the land. Still, observers eventually noticed that “all savages do P” isn’t true for basically any P, and after some delay anthropologists stopped trying to argue that surely some X was actually a distant distorted cultural memory of P which all savages must have done in an even-more-savage past.

In the early twentieth century, anthropologists embarked on a more ambitious project - demonstrating that something about primitive culture proved that their own political faction was right about everything. Marxists discovered idyllic tribes untouched by capitalism, peacefully sharing their communal resources. Missionaries discovered that every primitive religion was merely a distorted form of Christianity, with a few extra gods and rituals added in to serve local appetites. Feminists discovered that women everywhere developed unique indigenous forms of resistance to patriarchal domination. Postcolonialists discovered that all the other anthropologists were racist. Freudians discovered so many things that it would take ten books of this length to even begin to talk about them.

The mid-to-late twentieth century is Hiatt’s own era; given his lack of distance, he holds off on making too many generalizations. There is widespread discontent at the excesses of previous eras, and ideologically-driven practice has fragmented into a grab-bag of more careful but less unified techniques. The responsible experts would never dream of something so declasse as having a paradigm.

But my own thoughts on anthropology have been shaped by two letter-S-intensive books. First, The Secret Of Our Success by Joseph Henrich (reviewed by me here). Second, Sick Societies by Robert Edgerton (reviewed by Jane Psmith here).

The former chronicles the wonders of cultural evolution. Seemingly “primitive” societies’ seemingly “barbaric” practices turn out to be brilliant beyond “civilized” man’s ability to comprehend. For example, the Montagnais-Naskapi tribe performs a divination ritual using an animal’s shoulder bones to decide where to hunt. This sounds stupid, but Henrich chronicles how the divination ritual actually has useful mathematics-of-randomness properties that makes it more likely to generate efficient hunting patterns than the tribesmen would get through normal decision procedures. The Aztecs performed a complicated series of rituals to corn before they ate it, mixing it with powdered shells; only in the 1900s did Westerners realize that this process activates vitamins; without it, anyone who eats too much corn risks dying of niacin deficiency. Henrich’s conclusion is that primitive tradition is a repository of wondrous practices selected by millennia of trial-and-error, and we pooh-pooh it at our peril.

The latter says: nah, actually primitive tradition is often just dumb. Edgerton goes through just as many examples as Henrich, but with the opposite moral: some primitive tribe had done something since time immemorial, but it was stupid and cruel and made their lives worse or, in some cases, pushed them into extinction. So for example (both quotes from the Psmith review, content warning for graphic violence applies to everything between here and section II):

Among the Pokot of Kenya, where brutal wifebeating was the norm, men often reported they only trusted food prepared by their mothers or sisters; their wives might poison them. Others said their wives were trying to kill them by witchcraft. Several women agreed that yes, they certainly were, and one woman told the ethnographers she had succeeded.

And:

The Dugum Dani of western Papua New Guinea were so notoriously warlike that when an Australian police post was introduced to the area, anthropologist Karl Heider predicted that it would do little to stem the Dani’s endemic violence. In fact, though, they quickly abandoned their warfare as soon as the presence of the colonial authorities gave them a plausible coordinating mechanism, and many later expressed relief that they were free of the cycle of violence and retribution. Similarly, highlanders who had practiced brutal initiation ceremonies “in which they were forced to drink only partly slaked lime that blistered their mouths and throats, were beaten with stinging nettles, were denied water, had barbed grass pushed up their urethras to cause bleeding, were compelled to swallow bent lengths of cane until vomiting was induced, and were required to fellate older men, who also had anal intercourse with them” gave them up after only minimal contact with outside disapproval. Some later told anthropologists they felt “deeply shamed” by their treatment of their own sons and were relieved to stop.

Many of these seem like inadequate equilibria, or multipolar traps - nobody wants to be the first person to skip the brutal initiation ceremony and look like a pussy. But other problems are just stupid. The Marind-anim were warlike raiders who stole other tribes’ children because their own women were infertile. Unbeknownst to them, their own women were infertile because of a “fertility ritual” where multiple men would rape each woman on her wedding night so violently that it destroyed her reproductive system. Eventually European colonizers made them stop, and their fertility miraculously rebounded.

(also, the story about the oracle bone divination hunting appears to be fake)

Edgerton and Henrich don’t come out of nowhere. They’re the modern reincarnations of Hobbes and Rousseau - with the former calling primitive life “nasty, brutish, and short”, and the latter idealizing it as an Edenic paradise to which we could only dream of returning. Nowadays both sides are in disrepute - young anthropology students are taught to abjure Hobbesians with the scornful incantation “White Man’s Burden”, and Rousseauians by uttering “Noble Savage”. Still, Edgerton and Henrich are proofs that ideas can never be fully banished, and under the surface the debate continues.

The Australian Aborigines are a tempting battleground for this conflict. Even as we’re not supposed to dub them noble savages, so we definitely aren’t supposed to call them “the oldest society in the world” with a “fifty thousand year history” - just because they arrived fifty thousand years ago doesn’t mean their culture has been stagnant during that time. Still, certain decamillennia-old rock art appears to depict some of the same beings mentioned in Aboriginal mythology during colonial times and into the present. And on a very literal interpretation of cultural evolution, the longer you’ve been in a specific niche, the more adapted to it you get. We are citizens of an industrial society that gets five or ten years to adopt to each new paradigm before the technologists throw out something new to knock us off balance again, heirs to a Judeo-Christian tradition barely three thousand years old and a Greco-Roman-Indo-European tradition hardly any older. What does something really ancient look like? The Aborigines, whose culture can seem impossibly complex at times (is this an illusion? we’ll discuss that later!) give a feeling of something over-optimized, a genetic algorithm run for 999,999,999 epochs until it ends up at weird edge cases that break the reward module and get assigned infinite utility.

It also seems, in other ways, pointless, cruel, and dysfunctional along axes I didn’t even realize were possible. So let’s dig up the corpses of Hobbes and Rousseau and let them duke it out some more.

II.

Australian Aborigines are a polygynic gerontocracy with infant betrothal.

When an Aboriginal man comes of age, he gets mock-abducted from his parents by unrelated elders and forced to spend five to fifteen years going through a series of grueling initiation rituals. During some parts of the rituals, he must spend months isolated from all other humans, living on his own in the wilderness. During others, he endures horrible mutilations, starting with circumcision and only getting more horrifying and creative from there. The more initiations he goes through, and the more secret societies he joins, the cooler and higher-status he becomes.

Somewhere in this process - before, during, or after, depending on the tribe and situation - he is matched not with a wife, but with a mother-in-law. He promises to serve the mother-in-law and her husband for his remaining adolescence and young adulthood, doing chores for them and bringing them his best food. In exchange, the mother-in-law promises him her (perhaps not yet born!) daughter’s hand in marriage. If he’s really cool, she may promise him all her future daughters in marriage.

The marriage takes place after the daughter reaches puberty. At this point, the man - who was probably fifteen or so at the time of betrothal - is probably in his thirties. So a modal marriage might be between a 30 year old man and a 14 year old woman. And this is the best case scenario: if a future mother-in-law has five sons before her first daughter, maybe the man is 40-something by the time he’s wed.

This system is great for old men, who get lots of young wives, plus the devoted service of the tribe’s adolescent men, plus they get to dress up as cool gods and demons and freak everyone out at initiation ceremonies. It’s terrible for women, who are married off to men 20 or 30 years their seniors without being asked. And it’s also terrible for young men, who have to remain celibate into their thirties, get various body parts mutilated in weird rituals, and spend the best years of their lives serving future in-laws. Why and how does this system endure?

We’ll return to the why question later. The how question is the subject of most of the individual case studies in the book, starting with:

III.

Americans like to trip up their politicians at town halls by daring them to answer how many genders there are. The Aborigines would not be tripped up. They would immediately answer eight.

“Gender” is technically the wrong term. Most anthropologists use words like “section”. But there are some notable resemblances. Your “section” determines who you are, how people address you, and (especially) who you can marry.

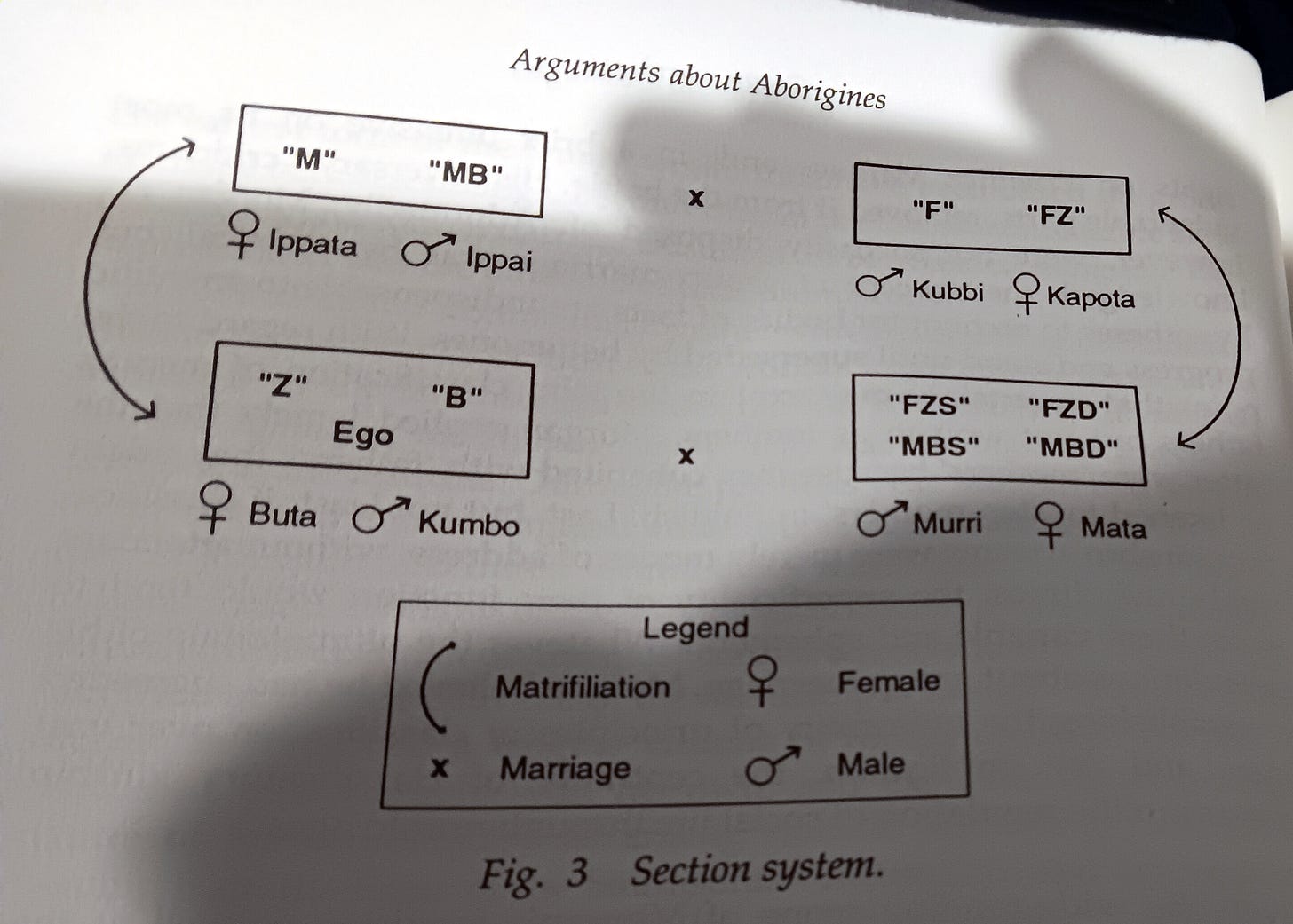

The details vary from tribe to tribe, but Hiatt describes the section system of the Kamilaroi of New South Wales:

Suppose I, a man, am Kumbo. Then all of my brothers are also Kumbo, and all of my sisters are Buta, the female counterpart of Kumbo. My father and his brothers are Kubbi, and their sisters are Kapota. I may only marry a Mata woman, and our sons will be Kubbi.

Further, everyone of the same section is . . . sort of the same person? My father’s brothers, who are Kubbi like him, are also sort of my fathers. If I visit a far-off tribe, the Kubbis there will behave paternally to me, and I owe them some measure of filial respect. Likewise, I may call all Butas “sister”, and all Ippata “mom”. I can never have sex with any Buta or Ippata - that would be incest.

You can take this pretty far! If I tell another Kumbo “Look, we are in some sense the same person, therefore I should be allowed to sleep with your wife”, this . . . actually sometimes works? I’d want to have a very good pre-existing relationship, and I’d owe him a favor, but it could happen!

This system might seem pointlessly complex, an exercise in building castles in the air. But in the late 19th century, anthropologists from distant lands compared notes and noticed that the Iroquois of North America do the same thing, as do other scattered groups across several continents. So there must be some underlying logic. What is it?

Lewis Morgan, the American who first made the discovery, suggested it was a relic of ancient group marriage (cf. grand 19th-century stage-based Theories Of Everything). Suppose that primitive cultures married entire families: a group of brothers from one family marries a group of sisters from another. This might explain the Australian system. If you didn’t know which sibling of a group was your father, then you might want to use the same word for “father” as for “paternal uncle”, for “brother” as “male cousin”, and for “husband” as “husband’s brother”, since there was no way of keeping track of which was which. Extend these principles, and you get something like the Australian system.

This was clever, and there was even some circumstantial evidence: Aboriginal brothers did sometimes lend one another their wives, as mentioned above. It didn’t take an anthropological genius to guess that this sort of fraternal wife-swapping might be an adaptation to the grueling difficulty that young men had in getting a wife the usual way. And it also had side benefits: Aboriginal men were frequently out on very long hunting trips. They were both concerned for their wives’ welfare (how would they defend themselves without a man around?) and jealous (what if they tried to sleep with someone their own age?) Lending one’s wife to a brother (who, again, was basically the same person as you) or even a non-relative person of your section (who, again, was technically your brother and therefore basically…) was a pretty wild way to avoid feeling cuckolded, but apparently seemed to work.

What if your brother (or other fellow sectioner) had sex with your wife, and you ended up raising a child that wasn’t yours? Here the Aboriginals again doubled down on their strategy of solving seemingly minor problems with dramatic culture-wide interventions: they simply denied that sex led to conception! (sort of, kind of, read the whole chapter here for more) Conception occurs when a child’s father ritually summons the spirit of his clan to impregnate the mother. It’s his child because he was the one who summoned the spirit, plus because he summoned his clan spirit. If the child was conceived when his brother or fellow-sectioner was with his wife - well, sometimes the spirits come at unexpected times.

But this doesn’t fit Morgan’s theory, where nobody knows or cares who the real father is. And wife-swapping between brothers was hardly a default - when it happened at all, there was a formal ceremony, and even afterwards the first brother was still the “real” husband and the secondary brother just a substitute. And there were other problems: why does the section system use the same word for “mother” and “mother’s sister”? It’s hardly mysterious who a given child’s mother is! A new wave of anti-Morgan anthropologists argued that the section system wasn’t as extreme as it had seemed to their predecessors: is it really any weirder for Aborigines to call all Kubbi men “father” than for Southerners to call any young man “sonny boy”, or for Western men to call their mothers-in-law “Mom”?

As anthropology advanced, it became less interested in theories about what primitive universals an institution might be a relic of, and more interested in asking what function the institution served. Here the scholars were on somewhat firmer ground. The section system was one way of preventing incest in a world where everyone was traveling and wife-swapping regularly, there were no written records, and nobody was keeping great track of whether someone from another clan was secretly their half-sister or cousin. Assuming everyone followed all the rules, there was no way that a legitimate marital partner could be any closer than a second cousin; most would be much further.

But also, the system divided people into groups that cut across more obvious groupings like clans and tribes. If I visited another clan, I would have some people there who considered themselves sort-of-in-some-sense my father who might offer me hospitality on that basis; other people who would be sort-of-in-some-sense my brothers who I could hang out with, and a pre-selected set of women who were sort-of-in-some-sense my wives and who I could pursue romantically.

Just as in the US a Jew who moves from NYC to SF might seek out the local Jewish community and expect a warm welcome from people who were in some sense “related” to him even if not quite in a literal familial way, so a Kumbo could go anywhere in Australia and find a place in the social network.

IV.

Just when you think you’re starting to understand this Australian Aborigine stuff: why is there a special language you only speak when you’re close to your mother-in-law? And how come, when you hear certain obscenities, you have to attack all of your sisters with spears?

First, the mother-in-law languages. This is another one of those things that sounds like some kind of wild one-off but turns out to recur across cultures all over the world. In Australia, they take the form of “fifty or so substitutes for the most common words in everyday discourse, although in certain cases they have been elaborated to the point where they function for practical purposes as independent languages”. They are spoken in cases where your mother-in-law is especially salient, including when talking to your brothers-in-law or when your mother-in-law is within hearing range. They’re not languages you speak to your mother-in-law, because talking to her directly is taboo and no Aborigine would ever do it.

Also taboo: looking at your mother-in-law, touching your mother-in-law, and getting too close to the 12.5% of the population who are basically your mother-in-law because they belong to the same section as her. The monstrous mother-in-law recurs again and again as a character in myth and fable, usually as a member in good standing of the penis-stealing witch brigade:

Ancestral women called Ganabuda were travelling across the country in a group. A Lizard Man named Spiky Head seduced a women related to him as a potential mother-in-law [ie someone from the mother-in-law section; for a Kumbo, this would be Kapota]. He had a penis capable of proceeding underground and rising to the surface under the object of his desire. The Ganabdua women attacked his testicles with sharpened digging sticks, cut off his penis, and killed him.

The Ganabuda women encountered Crow Man, who proceeded to have sexual intercourse with a young potential mother-in-law, as well as a classificatory mother’s mother [ie someone from the mother’s mother’s section; for a Kumbo, a Buta]. His mega-penis inflicted severe injury upon them, and they died. The Ganabuda women then killed the Crow Man.

An ancestral man named Dangidjara had intercourse with a potential mother-in-law. He then went hunting and brought meat back to her. Eventually she gave birth to a son. Dangidjara continued his journey. One day ants bit his genitals, which detached themselves from his body and ran away. He pleaded with them to return, but they refused. Eventually he retrieved them.

According to Hiatt, the Aborigines still haven’t gotten over this particular leitmotif:

Some years ago the wife of the Prime Minister of Australia was presented with an Aboriginal painting depicting an old man who developed ‘a grossly enlarged penis as a result of having sex with his mother-in-law’.

All of this coexists uneasily with the fact that a man must negotiate with the (future) mother-in-law in order to promised a bride in the first place, and that he must spend years serving his future mother-in-law (presumably with the help of intermediaries) in order to “earn” the bride when she comes of age.

What’s going on?

Nineteenth-century anthropologists didn’t bother to invent a grand Theory of Everything about this one. They thought it was obvious: mother-in-laws suck. Hiatt writes that Freud believed that the custom “had a good deal to commend it”, and he cites a letter from the great psychologist to his fiancee where he said of his own impending mother-in-law that she was “alien and will always remain so to me. I seek for similarities with you, but find hardly any … I can foresee more than one opportunity of making myself disagreeable to her and I don’t intend to avoid them”. This is funny, but also raises the question: if so many primitive societies have mother-in-law taboos, and our more “liberated” society still has an expectation and archetype that sons will hate their mother-in-laws, are these coming from the same place? And what is that place?

At least in the Australian case, twentieth-century anthropologists note two relevant facts.

First, in a culture where old men marry younger women, a man is the same age as his mother-in-law. A man just starting the process of earning a bride might be 18, his mother-in-law might also be 18, and his father-in-law might be 38. The man will then spend the next 15 - 20 years essentially celibate, serving the in-law couple in the hopes of earning a bride when he in his thirties. It must be tempting for the man to just cut out the middleman and have sex with the same-age mother-in-law directly. It must be equally tempting for the mother-in-law, hitched to a man twenty years her senior but now being served by this strapping young lad, to allow and encourage such a relationship. Hiatt collects evidence that none of these temptations escaped the notice of Aboriginal men. What’s a jealous father-in-law to do? Aboriginal elders took the nuclear option, layering every taboo they could think of over the idea of such relationships.

Second, remember that the man has been promised the mother-in-law’s female children (definitely at least the first, sometimes even more) as his bride. He really really does not want to accidentally father her female children! And since the Aborigines deny that sex leads to conception, you can’t just tell him why it’s a bad idea for him to have sex with the woman who will birth his future wife. The best you can do is spread rumors that she is definitely a penis-stealing witch, plus make him so creeped out by her that he has to speak an entirely different language when she’s in the area.

(the second factor is Australia-specific, but I leave as an exercise to the reader whether the first factor has any relevance to the weaker forms of mother-in-law hatred found in civilized nations)

But how come, when you hear certain obscenities, you have to attack all of your sisters with spears?

This custom, called the mirriri in the tribes Hiatt focuses on, is an anthropological favorite. The attacks are somewhere between ritualized and real, and sisters do occasionally get seriously wounded. The most common provocation is when a man hears his sister’s husband curse her. But the sister he attacks with spears might not necessarily be the same sister who got cursed, and sometimes other quarrels (for example, a sister vs. the sister’s daughter) could provoke the same response.

Early theories focused on the brother-in-law relationship. If a husband quarreled with his wife, there might be some lingering fear that the wife’s brothers would intervene on her side, thus turning a marriage that should have been an inter-clan alliance into an opportunity for inter-clan conflict. Just as men defuse the fear of sex with their mother-in-law by ritually hating and fearing her, so brothers-in-law could defuse the fear that they would take their sister’s side in a conflict (and so start an inter-clan war) by ritually reviling and attacking her. And maybe this display would work even better if they attacked random other sisters too, just to drive home how little they cared about sororal bonds.

This theory floundered on the observation that although the most classic cause for mirriri was a sister-vs-brother-in-law conflict, any sister-related conflict had the potential to provoke the response, even when there was no marriage or inter-clan alliance involved. So the next generation of anthropologists concluded that - yeah, it’s an incest thing again. If you’re keeping young people in a decades-long state of sexual frustration, maybe their sisters start to look pretty good; certainly the past few years of online pornography have suggested that this option is never far from the sexually-frustrated-young-person mind. Not only would such a relationship have the usual downsides of incest, but it really could blow up alliances and start an inter-clan war.

Many Aboriginal conflicts involve screaming insults at each other, and many of those insults are sexual. So an Aboriginal man hearing a conflict with his sister probably hears a lot of descriptions of her genitals, sexual proclivities, etc. Maybe this is awkward enough that he feels the need to signal how aroused he isn’t the most dramatic way he knows how - trying to impale her with a spear (this signal would not have survived Freudian psychology). And maybe, just to hammer in how little he gets aroused by sisters, he has to try to impale all of them with spears.

Don’t keep your culture’s young men in a decades-long state of sexual frustration, that’s my advice.

V.

Whenever race-and-IQ types talk about the intellectual advantages of Western Man, someone shows up to tell them that they wouldn’t last a day in Aboriginal Australia. I am sure this is true. Plop me down in Arnhem Land, and it would take five minutes before I forgot whether it was Kubbi or Murri that was taboo relative to Kumbo, accidentally had sex with my classificatory sister, and got speared by ten clans simultaneously.

Reading this book - only a fraction of which I’ve been able to represent here - it’s hard not to be awed by the complexity of Aboriginal society. Is cultural evolution showing off what it can given 50,000 years to work with? Or does every society seem this byzantine to foreigners who are 50,000 years removed from the most recent common ancestor?

If some Aboriginal anthropologist came to America and tried to list our sex taboos, what would they find? No sex between close family members up to second cousin, that’s obvious. No sex with bosses, subordinates, or clients. A strict taboo on even mentioning sex at work, enforced by a caste of powerful witches called “HR ladies”. Acknowledging even the slightest attraction to anyone under 18 makes you a monster, but people who are just slightly older than 18 - even by one day - are called “barely legal” and feature especially prominently in sexual imagery. No sex across “age gaps”, where some people define “gap” as “half your age plus seven” and other people refuse to define it but reserve the right to judge transgressors anyway. Men can’t have sex with other men, unless they’re part of a special caste called “gay people” who must move to New York, speak in a weird voice, and cultivate an interest in musical theater. Married people can’t have sex with anyone besides their spouse, unless they’re part of a special caste called “poly people” who must move to San Francisco, dye their hair, and get jobs in tech. At some point maybe our hypothetical anthropologist starts longing for the simplicity of someone telling him which 12.5% of the population are his classificatory wives.

Should we take this seriously? Some Western taboos are just the local versions of cultural universals - no culture is pro-incest, and most place some kind of limits on pedophilia. Do we just have the basics? Does every tribe think their culture is just a variety of “the basics”? Do we have anything as weird as mother-in-law languages?

VI.

Let’s return to the question we punted earlier: why?

Grant that these taboos / rituals / etc make sense as part of the project of stabilizing this polygynic gerontocracy where thirty-something men marry pubertal women. Why would anyone arrange a society this way?

Hobbes might ask - why worry about the why question? Sometimes old people get the upper hand in a society and successfully implement a gerontocracy that benefits them while screwing over everyone else. There’s no law of physics saying this can’t happen, and there are plenty of Substack articles with the word “Boomer” in the title asserting that it happens even today. If young men and women can’t band together and protect their interests, that’s a skill issue.

Rousseau might suggest we hold off until we hear the Aboriginal elders’ side of the story. The final chapter of Arguments hints at this perspective. In one of their initiation ceremonies, the elders chop, boil, and otherwise process a species of yam which is poisonous in its raw state but edible with sufficient preparation. Then they symbolically go through the same steps with the young people being initiated into the cult. The lesson seems to be that young people, like yams, start out toxic and inedible in the raw, but can become socially useful after sufficient preparation. Young people are dumb, violent, and horny. As long as they’re kept subservient to the elders, they can’t do anything stupid like start a war, or marry for love instead of inter-clan-alliance-formation.

And (the elders might continue), handing us control of everything has gone pretty well. In one paragraph, which Hiatt places half in his own voice, half in the voice of anarchist-leader-and-amateur-Australian-Aborigine-scholar Peter Kropotkin, he says:

Few peoples can have placed higher value on altruism and mutual aid than the Aborigines of Australia. The genius of the Australian polity lay in its deployment of the goodwill inherent in kinship as a central principle of organization for society as a whole. Government in these circumstances was otiose; its absence, Kropotkin would say, was to be regarded not as a low level of political evolution but as a luminous peak. Natural resources and the land itself were equitably distributed among descent groups; appropriation of clan estates by force was unknown, and theft of private property a rarity. The business of everyday life was conducted informally through unspoken understandings, quiet consensus or noisy agreement. In general the authoritarian mode in public affairs was discountenanced. Vanity and self-importance were mocked. Nearly everywhere men insisted on speaking for themselves and, conversely, evinced a reluctance to speak on behalf of others.

Still not noble enough for you?

[During the early days of the colonization of Australia], fifteen convicts were flogged for allegedly setting out to plunder a native [ie Aboriginal] encampment at Botany Bay. The reason for the punishment was communicated to [local Aboriginal representative] Arabanoo, who was brought along to witness it. He was not impressed; instead of expressing gratitude to the authorities, he evinced only disgust and terror. When a large group of Aborigines was assembled two years later to watch the lashing of a convict caught in the act of stealing fishing tackle [from them], all reacted with abhorrence to the brutishness of the spectacle. One of the women went so far as to snatch a stick and menace the flogger. Tench noted that on a previous occasion when a bundle of stolen spears had been recovered and placed on the beach, an old man came up and singled out his own from the rest: ‘and this honesty, within the circle of their society, seemed to characterize them all’. Sharing, moreover, was commonplace and spontaneous, as evidenced by Arabanoo’s gifts of food not only to his countrymen but to the colonists’ children who flocked around him.

Aside from the whole gerontocratic-patriarchy-with-decades-of-mutilation-and-sexual-frustration thing, and maybe the decamillennia of technological stagnation, Aboriginal society has much to recommend it. There is broad inter-clan peace, social equality (modulo age and gender), and enough mutual aid that nobody goes hungry unless everyone does. Neighboring tribes get along, there’s no religious warfare, and you spend large portions of your time dressing up in cool costumes and terrifying people with bull-roarers. Don’t accuse me of noble-savaging - I’m just speaking for some combination of a hypothetical Aboriginal elder, L.R. Hiatt, and Kropotkin.

Okay, says Hobbes, sure, large-scale organized violence was rare. But high-single-to-low-double-digit percents of the population died of small-scale disorganized violence, far higher than the murder rate even in very dangerous countries like America or pre-crackdown El Salvador. And although anthropologists still debate exactly why Aborigines practiced so much infanticide, one pretty popular position is that women were trying to punish their husbands for all the forced marriages and beatings, using the only cudgel that they had. Also, aren’t we cheating by not talking about those initiation ceremonies in greater depth? It’s not just the circumcision! Have you ever looked up “subincision” on Wikipedia? I don’t recommend it!

Sure, says Rousseau, but may I present as Exhibit A pages 181-182, from a chapter focusing on a rare non-horrible initiation ceremony among the Tiwi people of the the Northern Australian islands:

On Bathurst and Melville Islands, as on the Australian mainland, suicide in traditional society seems to have been unusual if not unknown. In recent years, however, there has been an outbreak of self-mutilation among Tiwi young men. According to Gary Robinson, a contributing factor is prolonged psychological dependence on maternal kin, well beyond adolescence, and a conflict-laden enmeshment in the the vicissitudes of the paternal family. Traditionally, as we have seen, this would have been impossible. At puberty, a lad was ritually removed from his family surroundings and placed under the tutelage of outsiders. More importantly, clearly defined status objectives were implanted in his mind, and by the time he had attained them by passing through a series of initiatory grades, he was ready to marry and start his own family. Masculine values were reinforced through regular engagement in male corporate activities, particularly hunting, fighting, and ceremonial; while idealization of the father, who by now was unlikely to be alive, provided an individualized role model for the firm delineation of personal identity.

The Tiwi say that when a boy’s public hair begins to grow, dogs bark at him in camp and crocodiles and bulls chase him in the bush. In the old days, the source of provocation was forcibly plucked out [that is, they pulled out all his pubic hairs in an initiation ceremony - “non-horrible” is a matter of degree!] As a son’s burgeoning sexuality was potentially a destabilizing force in his father’s harem, the preservation of paternal and filial goodwill depended on separation through the institution of initiation, followed by the son’s growing absorption in the corporate affairs of men (which included the cultivation of patronage necessary for the promise of a wife from outside his own band). All these traditional structures have now collapsed, and nothing viable has been put in their place. The transition from childhood dependence to adult autonomy, once mediated by external authority, is now beset by incoherence and uncertainty of aims. The family itself is the remaining authority, and children often lack the motivation to solve their problems by making a clean break with it. Ambivalence inherent in the father-son relationship remains unresolved and a source of instability, fluctuating between violence and mutual aid. Young men have nightmares about death, and suffer chronically from melancholy, depression, and rage.

In 1986, three Tiwi brothers travelled to the mainland in order to establish contact with a descendant of one of Joe Cooper’s buffalo-shooters, related to them as a classificatory father. They had fantasies about being initiated and in the process acquiring power to win fights, get women, and in general overcome their anomy. The pilgrimage proved futile. Within a short period following their return to Melville Island, one brother had narrowly survived a suicide attempt after grasping an electrical power line. Another, just before his thirtieth birthday, broke into a store and hanged himself while awaiting police questioning.

This is an all-too-common pattern when hunter-gatherer societies are forcibly integrated into sedentary nations - see eg my review of The Arctic Hysterias for more. It’s so common that we’re no longer surprised - of course colonialism is bad for these people’s mental health.

But maybe it should feel more mysterious. When Third World immigrants move to the US, they’re usually pretty happy with their decision. They might not assimilate completely, but they’re often able to hold down jobs or at least avoid spiraling into alcoholism and suicide. But when a people gets colonized - after the bad part with the conquest and land theft and oppression, once they’re granted citizenship and the settlers feel vaguely apologetic - doesn’t it end up kind of like being an immigrant into a First World country? In fact, isn’t it strictly superior? Instead of dodging ICE goons, you get full citizenship, access to the welfare system, maybe some affirmative action. You don’t even have to abandon your family or leave your ancestral village.

Is this latter part the problem? The typical immigrant moves to New York and gets a job as an Uber driver for rich people. Maybe it’s worse if you stay on a reservation where everyone else is as poor as you? Maybe this is the same problem as decaying Rust Belt / Appalachian towns, or the post-industrial British heartland. When everyone else in your area is as poor as you, the poverty feeds on itself?

But that raises a second question: a modern Aborigine has two options. They can move to Sydney or Melbourne and try to assimilate, in which case they’re no worse off than any other poor immigrant, and better than most. Or they can stay in an Aboriginal village. If Hiatt is to be believed, Aboriginal villages weren’t mental health disasters when they were following their traditional ways. But in absolute terms, they’re much richer now: nobody starves, there’s decent medical care, people have quality clothes and houses, etc. So what’s gotten worse?

The obvious answer is something like pride. Even if the average Aborigine has more stuff now, they get it from something like convenience store work or welfare or something, and this is less pride-inducing than being a traditional hunter (even if traditional hunters had less stuff and often starved). Still, really? Pride? The difference between a flourishing traditional lifestyle and spiraling into alcoholism and suicide is some sort of belief that hunting kangaroos is inherently masculine and cool, but working a minimum wage job is inherently cringe? Something like this has to be true, but I can’t make myself understand it. Also, even if Aborigines have been forced onto marginal lands, the Inuit mostly stayed in the same spot - those who want to continue hunting can. What equilibrium traps them in between two worlds, either of which seems better than the limbo in between?

(in the Inuit case, it seems to be that traditional lifestyles are so miserable that nobody would ever do them if they had any other option, even a marginal existence of welfare and alcoholism - but it’s not exactly the same kind of misery that causes post-colonial alienation, and there’s some other sense in which the post-colonial alienation is worse. I think there’s a lot to unpack here.)

Hiatt seems to think the damage centers around the disappearance of the initiation system. In traditional Aboriginal society, young men would be isolated from their family for a period of many years while they underwent a series of tortures expected to eventually result in a high-status social role within the community. The West has the same system: we call it “grad school”. But Aborigines do poorly in Australian education, with below 10% graduating college despite increasingly intense affirmative action (a decade ago, before this push, it was below 1%). It probably sucks to go from an initiation system where you have the same fair chance as everyone else, to a different initiation system, designed by a foreign culture whose own adolescents are much better at it than you are.

While we’re swinging from Rousseauian noble savage aficionados to Hobbesian White Man’s Burden paternalists, what would it look like to design a society that took Hiatt’s critique seriously? Would it be humane to dole out welfare checks whose size is proportional to how many degrees of Freemasonry the recipient can attain? How many points they can score at in some kind of artificial boomerang-throwing contest? Would young people go off to join the Freemasons and spend years practicing boomerang-throwing, then come back as high-status members of society able to attract a wife and support a family? Would they be happy?

With the benefit of one (1) anthropology book, the best I can do is say that traditional Aboriginal society seemed remarkably well-adapted to being what it was, but that what it was seems pretty terrible and I’m glad I never had to participate it. Still, my participation in it was never an option, many Aborigines are being forced to participate in my crazy society, and they don’t seem to like that either. The greatest anthropological argument of all is as tough as ever.